BALTIMORE -- Dozens gathered here Thursday evening in front of City Hall to protest the cash-strapped city's decision to send shutoff notices to roughly 23,000 homes to cover some $40 million in overdue water bills.

Amid chants of "Keep the water on!" and "Water is a human right!" community members came to the podium to ask the city to put a moratorium on its planned water shutoffs, provide more assistance to low-income families struggling to pay their bills, and prioritize collecting from the 369 businesses that owe nearly $15 million of the overdue cash.

"Even if one family is denied access to fresh water, that's one family too many," said Father Ty Hullinger, from a group called Interfaith Worker Justice.

Matt Hill, a staff attorney with the Public Justice Center in Baltimore, told the cheering crowd that his group is pursuing legal action against the city. "This isn't right. This isn't a fair shake. It's not due process," Hill said.

These wide-scale shutoffs have made headlines here in Baltimore, just as they did last year in Detroit, where water was shut off in 31,000 homes, city officials told BuzzFeed News. Public health experts say these policies can have dire consequences, from contagious gastrointestinal illnesses to skin infections, and the United Nations has said they violate basic human rights.

Yet water shutoffs are surprisingly common in the U.S. BuzzFeed News asked officials in the 10 biggest cities about their policies on delinquent water bills, and five responded with their data. New York City was the only one that does not shut off water, though it does, eventually, place liens on the property. Los Angeles, Houston, Philadelphia, and San Diego shut off between 14,000 (Los Angeles) and 26,000 (San Diego) properties last year.

What these numbers don't say, however, is how long residents went without water. In San Diego, for example, most of the time water was turned back on within a day or two, officials said. Many activists say that shutoffs are far more worrisome in cities like Baltimore and Detroit, where low-income populations may struggle to front the cash to get their water turned back on quickly.

"We have done this for years and years — in that regard, there's nothing new about it," Jeffrey Raymond, spokesperson for the Baltimore Department of Water, told BuzzFeed News. "It's not a terribly happy part of what we do, but there have been turnoffs. Should it get to that point, that's what we have to do."

Baltimore’s water department stops shutting off water during the cold winter months and resumes every April.

But this was the first year that the city made a public announcement about the number of planned shutoffs, Raymond said. "We did an announcement this year in an effort to be more open about the process," Raymond wrote via email, adding that he didn't have the figures for how many planned shutoffs they had this time last year.

The news was a shock to many Baltimore residents. "It came out of nowhere for us," Hill, from the Public Justice Center, told BuzzFeed News. "I think this is a new, more aggressive policy — despite what the city is saying otherwise."

Last year, according to Raymond, the city shut off water access to just over 2,000 residences, and in 2013 to about 4,500. This year's numbers, he said, are likely to be in the same ballpark.

The numbers are difficult to pin down because many people scramble to pay their bills or make other arrangements shortly after getting their shutoff notices. Last week, the first week of its program, Baltimore cut off water to 350 accounts with balances in excess of $250 or bills left unpaid for six months. As of Tuesday, 132 of those were turned back on after people paid their bills.

About 1,000 accounts arranged for payment plans, formally contested their bills, or applied for low-income assistance, Raymond said.

The shutoffs will continue weekly until the 23,000 delinquent accounts are accounted for.

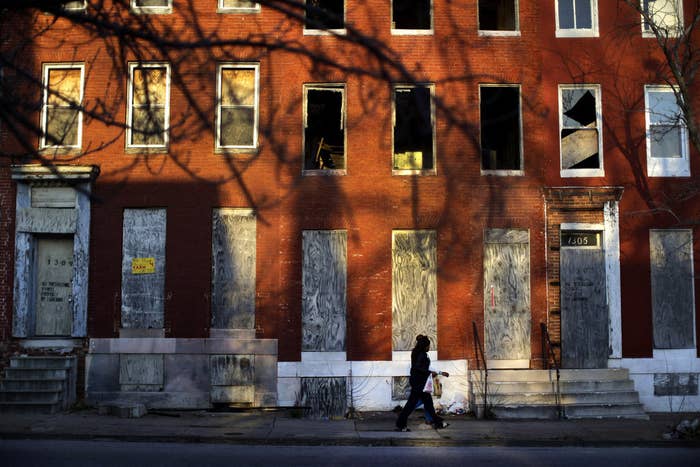

Poor communities are hit hardest by water shutoffs.

"Low-income residents pay a disproportionate amount of their income towards water and sewage services," Mary Grant, a Baltimore-based researcher for Food and Water Watch, told BuzzFeed News. "This is a nationwide problem."

In Baltimore, more than one-third of the population has a household income of less than $25,000 a year, a poverty rate about twice the national average. On top of that, city water rates have been steadily rising by more than 10% every year for the last four years.

The rising rates, combined with widespread irregularities in the city's accounting, have put the squeeze on many of Baltimore's low-income residents.

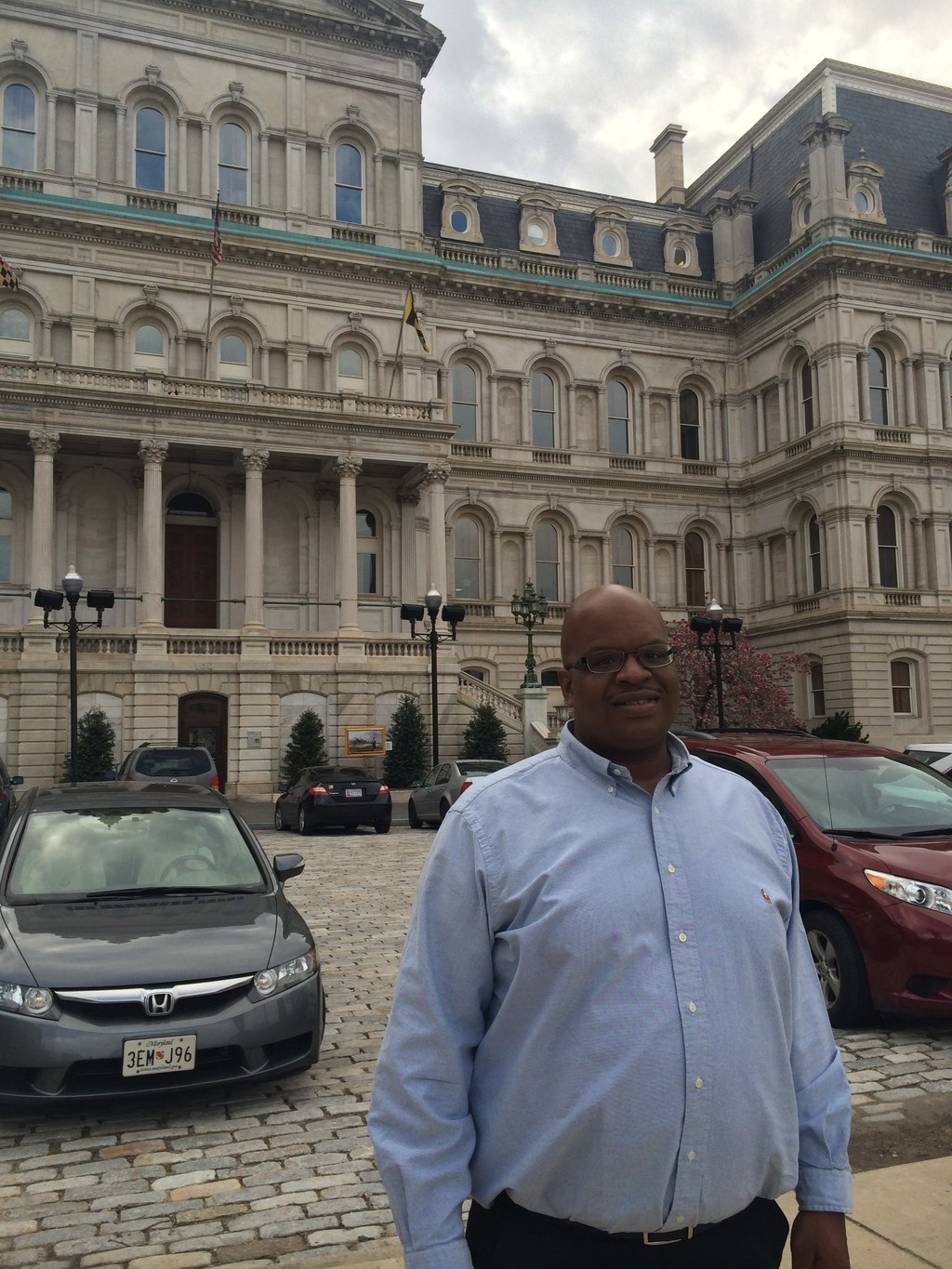

At Thursday's rally, Damian Henson, a 43-year old homeowner who works by day as the general manager of a Wendy's in Baltimore, told his story. Like many others in the city, Henson began to have issues with his rising water bills a few years ago. His bills, which he says used to hover at a steady rate of roughly $130 a quarter for nearly 10 years, suddenly shot up to $780. The city came and did an inspection of his meter, he said, but they couldn't find a leak.

Henson and his wife were unable to make the full payments on their bills, which he said were about $500 per quarter in the years since. With late fees, his current bill stands at roughly $3,800 overdue. In February, Henson received a notice that his water would be shut off in April.

"The city has to do something — this is too hard," Henson later told BuzzFeed News. "There's an unsilent majority here in Baltimore now."

Renters, who make up nearly half of Baltimore residences, have another problem. Because their names are not on the utility bills, they don't qualify for low-income government assistance.

Jessica Lewis, co-founder of the Right to Housing Alliance, a housing advocacy group in Baltimore, told BuzzFeed News that none of her constituents qualify for the city's low-income programs. "This is a huge problem for renters because they have no recourse to challenge water shutoffs, and no recourse to challenge outrageous bills due to landlord neglect," Lewis said.

Global human rights groups and public health experts denounce water shutoff policies on moral and legal grounds.

"This is a strategy which is very anti–public health in general," David Ozonoff, professor of environmental health at Boston University, told BuzzFeed News.

About 95% of the water that comes into a person's house is not used for drinking, Ozonoff noted, but rather for cleaning, waste removal, and bathing. Most of the serious health problems that come from living in a house with no water, then, have to do with not being able to stay clean — including contagious skin infections like staph and impetigo, or gastrointestinal illnesses like diarrhea.

"It makes a house uninhabitable," Ozonoff said. "If you're shutting someone's water off, you're essentially throwing them out of their house."

The United Nations agrees. "It is contrary to human rights to disconnect water from people who simply do not have the means to pay their bills," Catarina de Albuquerque, the U.N. special rapporteur on water, said last summer after visiting Detroit at the height of the shutoffs.

Although Detroit residents filed for a restraining order to prevent the city from continuing the shutoffs, the judge presiding over the case ultimately ruled that the courts did not have jurisdiction over the issue, saying that there was no "enforceable right" to water.

Detroit, like Baltimore, is planning to restart its shutoffs this month, city representatives told BuzzFeed News.

At the rally, Julie Gouldener, a representative from the advocacy group Food and Water Watch, told the audience that her group had asked the U.N. to intervene with Baltimore in the same way it had with Detroit. "When 23,000 people can't afford to pay their bills, it's a systemic issue."