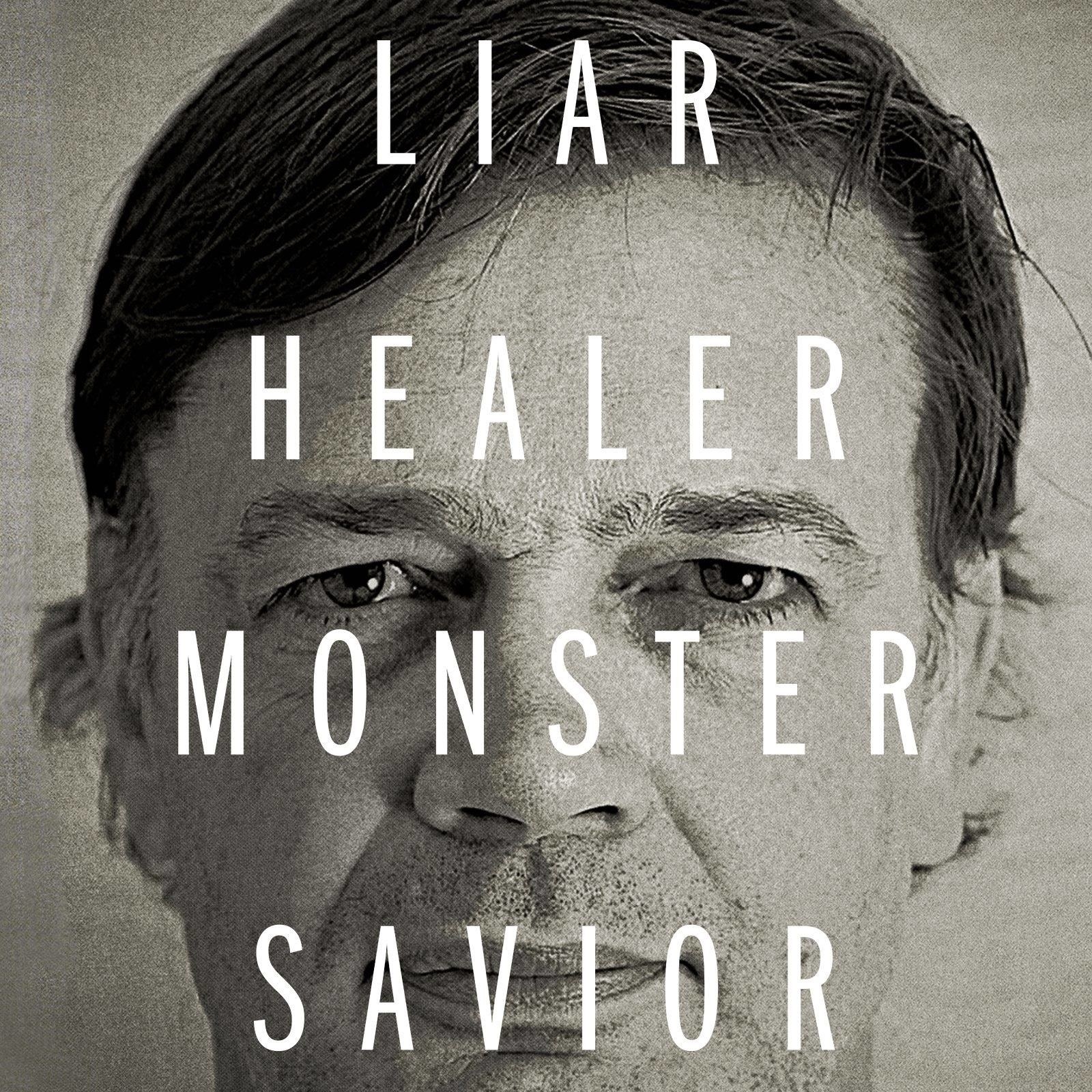

At one point in the new documentary The Pathological Optimist, Andrew Wakefield, the man best known for promoting the myth that the MMR vaccine can cause autism, likens himself to the South African revolutionary Nelson Mandela.

Wakefield was speaking at a chiropractors meeting in Southern California, where he had just raised more than $50,000 in a single evening. The fundraiser was ostensibly held to pay for legal fees in a defamation suit Wakefield had filed against Brian Deer, a British investigative journalist who alleged that Wakefield’s infamous 1998 study not only falsified data, but also made him money — nearly £435,000, paid by parents hoping to win a lawsuit against vaccine manufacturers.

Broad-shouldered but hunched over, Wakefield addressed the group with a steady gaze.

“People say to me, ‘Listen, you can’t win this can you?’” he said in his demure British accent. “I say, that’s not a reason not to fight. Mandela was in prison for 27 years in solitary confinement — how many people told him during that time that he couldn’t win?”

He was sitting at a table of the biggest donors at the event, some of whom had been shown writing him checks for $1,000. “What I’d love to do is come back in one year’s time, two years' time, and say, ‘Guys, we won the case. We won it thanks to you. And now the world is never going to be the same again.’”

Wakefield didn’t win the case. And given that he filed the suit against a British writer from his new home in Austin, Texas, he probably never had a real shot at winning it. But that doesn't matter. As this provocative, five-year documentary makes clear, the desperate parents who follow him will follow him anywhere. Just like every martyr, he only needs a righteous cause.

“To our community, Andrew Wakefield is Nelson Mandela and Jesus Christ rolled up into one,” J. B. Handley, co-founder of Jenny McCarthy’s anti-vaccine group Generation Rescue, told the New York Times in 2011. “He’s a symbol of how all of us feel.”

“To our community, Andrew Wakefield is Nelson Mandela and Jesus Christ rolled up into one.”

The filmmaker, Miranda Bailey, originally intended to focus the film on the defamation suit against Deer, whose investigations led not only to the retraction of Wakefield’s 1998 paper, but to the loss of his UK medical license in 2010. But when the judge ruled, in 2014, that the case had no jurisdiction in the state of Texas, Bailey had to change course.

“Miranda’s film had no third act — there was no story. So then it became a different story, a character piece,” Wakefield told me on Thursday, from a swanky hotel room in New York City’s Soho House where he and Bailey were doing press interviews. “It’s not the film I would have wanted, because I’m not interested in me.”

And yet, it’s clear he was game for a rebranding. Most people know Wakefield — if they’ve heard of him at all — as the British doctor who was stripped of his medical license and booted from the scientific community for hatching the bogus link between the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine and autism, but not before launching a lasting, dangerous panic in parents across the world. Over nearly 20 years, Wakefield has never backed down, even as dozens of studies have refuted his retracted original, which looked at just 12 kids.

“The image of me that’s been painted in the media is of this child-eating, horned monster,” Wakefield said, sipping tea. (He’s been profiled, sharply but fairly, by several big outlets.) “And the value of [the film] is, it’s just a guy trying to do a job.”

Wakefield’s job has changed several times since the scandal broke, when he moved his wife and kids from England to a sprawling Craftsman with a pool tucked away in the bucolic hills of Austin. Initially, Wakefield opened an autism treatment center there called Thoughtful House Center for Children, on a reported salary of £164,000 a year. He abruptly left that post after his medical license was revoked. Since then, he’s written books and made a movie of his own, claiming a massive cover-up by the medical and pharmaceutical industries. And through it all, he’s been soliciting donations from his devoted following.

The film frequently shows mothers of autistic children hugging him, asking to take photos with him, and, more than once, crying. At one event, mostly filled with moms who believe Wakefield’s assertion that the MMR vaccine was the cause of their children’s autism, he banks over $130,000 in donations. At a Starbucks after the event, a few of the moms, who refer to him affectionately as “Andy,” say that their goal is to raise him a million dollars by staging monthly fundraising events in his name.

The film portrays his wife and kids, too, as true believers. In a jarring scene, they gather around the kitchen table to cheerfully defend one of the most shocking stories included in the Deer investigation.

For his 1998 study, Wakefield found a control group of children who did not have autism in a strange place: the 10th birthday party of his oldest son, James. Wakefield took blood samples from kids at the party — some reportedly as young as 4. (He did this without the approval of his university’s ethics board, but allegedly with the consent of the kids’ parents.) The children were given £5 in their goody bags for participating.

The film shows the whole family happily looking through photos from that birthday party, joking about the events that would so shock the public. Wakefield’s fiery wife, Carmel, refers to a recording that had surfaced of Wakefield talking about the party, where he joked that two of the children fainted, and one threw up over his mother.

“It was just a standard 10-year-old’s birthday party,” James tells the camera, laughing. “And then, yeah, I read about it in the news as some horrific bloodbath. It blows my mind, it couldn’t be further from the truth. It was a great day...We were fighting to get in the front of the line. I pulled the birthday card and got to go first, gave blood, and that was it.”

Deer, whose investigation led to the discovery of the birthday party, is portrayed in the film as the embodiment of Wakefield’s many critics. Yet Bailey never interviewed Deer, nor any scientists, doctors, journalists, or anyone else outside of his trusted circle. Part of that, she says, is because no one would agree to be in a film with such a controversial subject. (In a series of back and forth emails all posted on Bailey’s blog, she and Deer have been arguing about whether she misled him about the point of the film when he declined an interview in 2012.)

“The whole thing is a commercial for Andrew Wakefield, from beginning to end,” Deer, who has now seen the film, told me over the phone. “It’s a scam to sell a product.”

The film does valorize the guy, sometimes resulting in cringeworthy moments. Several sequences in the movie show him flexing and dripping sweat during yoga, or chopping wood in his backyard.

“The whole thing is a commercial for Andrew Wakefield, from beginning to end.”

But if Bailey intended to make a piece of anti-vaccine propaganda, it’s certainly subtle. She consulted with scientists to get the science right. The many scenes of Wakefield claiming slippery defenses for why his research has come under fire are frequently juxtaposed with black cards stating the reported facts refuting his claims.

For Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, the film shows that Wakefield is a true believer whose arrogance motivates everything he does.

“Here’s a guy who went to medical school, trained in classic manner, published a paper, and was proven wrong — in 17 studies, performed in seven countries, on three different continents,” said Offit, who gave Bailey feedback on the film before the final cut.

“And yet he insists he’s right, to his own detriment. Why?” he said.“The reason is because he is Andrew Wakefield, and he can’t go wrong, because he’s Andrew Wakefield.”

Whatever you believe about vaccines before you watch this movie, you’ll feel all the more strongly after. It’s slick like that. Which left me wondering: What about Bailey? How did she convince Wakefield to let her embed with his family for five years? What does she really think about vaccines?

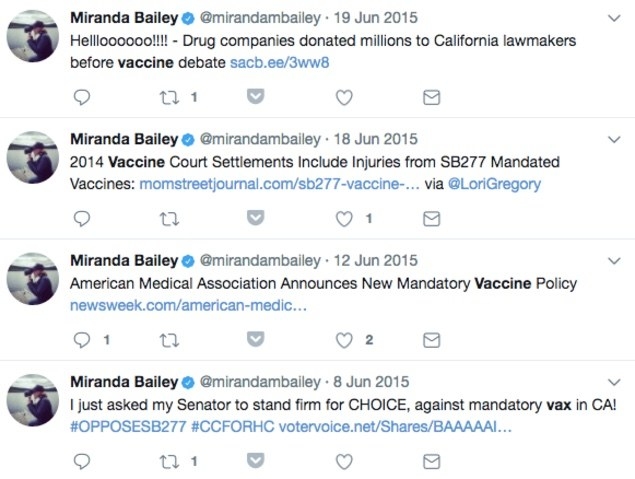

When I asked her, she said it shouldn’t matter, that the movie isn’t about her feelings. “But I believe that it’s not black and white,” she said after a pause. “I feel that it’s complicated. It’s a complicated issue.” And in 2015, Bailey opposed a California bill that barred parents from skipping vaccines due to “personal beliefs.”

In some respects, it doesn’t matter what they believe: Bailey and Wakefield will both financially benefit from the fringe of parents who believe anti-vaccine myths, no matter what. Wakefield says he’s now devoted to being a full-time filmmaker, and when I emailed him after our interview, he — confusing me for someone else — encouraged me to make a tax-deductible donation to support his new film.

Nearly 3,500 people are following the film’s Facebook page, and almost all of the comments thus far are from anti-vax parents, delighted to have an hour and a half of footage devoted entirely to Wakefield.

As the film says in its opening sequence, quoting Mark Twain: “It’s easier to fool people than to convince them that they have been fooled.” ●