In March 2015, as Singaporeans were publicly mourning the death of their country’s revered founder, Lee Kuan Yew, a 16-year-old named Amos Yee was busy putting together a celebratory YouTube video entitled “Lee Kuan Yew Is Finally Dead!”

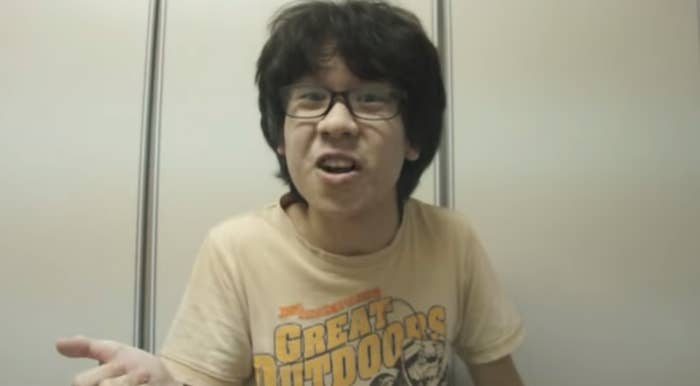

Addressing an imagined audience of millions in a pubescent falsetto, from the apartment he shared with his mother, the teen called Lee a megalomaniac, a dictator, and a fraud. He called the late politician a “horrible person” and “awful leader”; later in his eight-minute rant, he compared Lee to Jesus Christ. The analogy was not meant to flatter: Yee is a committed internet atheist who looks up to the secularist writer Richard Dawkins, chafes at political correctness, and admits to particularly enjoying going after Islam. Yee ended his monologue wishing the dead politician “good riddance.”

The rant spread quickly. (It’s now been viewed over a million times.) Eager to extend his 15 minutes, Yee followed the video by posting a drawing of Lee having anal sex with former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

Two days after he posted his video, he was arrested and thrown in jail under Singapore’s draconian speech laws. Over the next year and a half, his lawyers argue, he suffered sustained political persecution in his native country. After a slew of criminal charges, two trials, weeks in prison and jail, and a court order to stop posting on social media, Yee decided he’d had enough. On Dec. 16, 2016, he flew to Chicago and declared his intention to seek political asylum in the United States.

Like all asylum-seekers, Yee came here expecting to gain freedoms, not lose them. “I escaped to America so I could exercise my free speech,” he told me over the phone in April. “If I did that in Singapore, they’d send me to prison for a very long time,” he added, noting that be incarceration “is not economical. I had big ambitions.”

But Yee has now spent more time behind bars here in the United States than he ever did back home, waiting for hearings, motions, appeals, and counter-appeals to make their way through a byzantine bureaucracy that’s growing increasingly hostile to all foreigners, from skilled Swedish tech workers to Iranian grandmas. He’s getting a crash course in American social dynamics as he observes racial divides, economic inequality, and mass incarceration firsthand.

He’s also been offline for close to eight months. So much for that free internet.

Will America’s first troll government take in one of his own?

How Yee got here — and, indeed, why a citizen of a wealthy, sophisticated developed country would need to beg the US government for asylum at all — speaks to what happens when politics are global, but the right to express them is not. It’s a story about the regulation of the internet, and whether it’s reasonable for a government to grant its citizens the right to read and watch what they like online, but not express the views they form themselves. It’s about how a child’s blog can end up having lifelong repercussions; it’s about whether the Trump administration’s hard line on immigrants and refugees will extend to someone whom human rights groups around the world have described as a prisoner of conscience.

The results of Yee’s case could also set an important precedent: whether an individual whom the US government considers, in its own words, an internet “troll” can qualify for asylum by claiming political persecution. Will America’s first troll government take in one of his own?

Yee, who is now 18, cuts a familiar figure to anyone who’s browsed the atheism subreddit or gotten into an argument about the First Amendment with a contrarian debate team captain. He has long black hair; a squeaky, high voice; and the wispy pallor of an indoor kid. In jail, he’s been reading books by David Foster Wallace, and has gotten seriously into chess.

His ideology is a hodgepodge of au courant and often inconsistent convictions: He believes in unfiltered free expression, logical reasoning, and the practice of questioning everything. He hates religion, Singapore’s one-party state, and the conformist society he was brought up in.

If Yee were an American high schooler, he might be grounded. But Singapore thrives on order.

If Yee were an American high schooler, he might be grounded. But Singapore thrives on order. Many Singaporeans are brought up with deep-rooted Taoist, Buddhist, and Confucian values, conveyed at home and in school. You could compare the city-state’s penal system to a beefed-up, nationwide "broken windows" policy that aims to stop untoward behavior before it begins. If you litter, chew gum, or forget to flush in a Singaporean public restroom, you can be ticketed, fined, jailed, even caned. Homosexuality is illegal; you can’t buy or sell pornography. Police have even been known to bust public urination in alleys and elevators after the fact with special pee-detection devices.

What’s more, Article 14 of the Singaporean Constitution states that speech can be curbed “in the interest of public order or morality” so that citizens of the diverse country’s Chinese, Malay, South Asian, and expatriate communities can coexist in peace and prosperity. Publishers must obtain licenses to operate there; Singapore is 151st on Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom list, between Ethiopia and Swaziland. And there is a law that prohibits insulting people’s religions, much for the same reason.

The goal of these directives is to create a harmonious, considerate, prosperous society, but the consequence is a country that feels like it’s run by philosopher kings who got tired of the big questions and became management consultants instead. Alfred Dodwell, a lawyer who represented Yee pro bono in Singapore, called it a “benevolent dictatorship.”

Nothing conveys these mores quite like Haw Par Villa, a theme park on the outskirts of the city made up of a series of statues and gruesome dioramas depicting crime and punishment. Parents take their children there for a lesson in morality from the decapitated traitors, burning prostitutes, and disemboweled cheaters rendered in clay. Given the culture, Dodwell said, “when you have a teenager who’s hardly lived enough years to question anything coming up and speaking up against an elder, it’s frowned upon.”

By Singaporean standards, Yee had done something extraordinary in simply flouting the social contract. But to Americans, his trajectory sounds downright cliché: a classic case of alienation, frustration, and rebellion that happened to have played out in a socially conservative Asian city-state, not a suburban sprawl. In that respect, Yee is suffering from a common affliction: being born in the wrong place.

Yee’s video, and the lewd cartoon that followed it, wound up on the Singaporean government’s radar, apparently due to dozens of citizen complaints. It was not well-received: Not only was he acting out of line as a child, he was also criticizing an adored political figure. On March 29, two days after he published the video, Yee was arrested and charged with spreading obscenity, the “deliberate intention of wounding racial or religious feelings,” and “threatening, abusive or insulting communication.” His bail provisions mandated that he stop posting on social media in a public fashion. He flouted them, crowdfunding his legal bills and writing to his followers on Facebook.

This resulted in another arrest. He spent the night in jail before a relative bailed him out and Dodwell offered to represent him. The lawyer got more than he signed up for. “I thought it would be a simple case of representing a boy,” he recalls. “Not an international phenomenon.”

Yee’s first trial took place that summer. He was found guilty of uploading obscene content and offending Christians. In a presentencing report that June, he was described as showing signs of autism, then taken to a psychiatric hospital for “reformative training” for two weeks, where he was held in solitary confinement, tied down, and forcibly medicated, according to legal documents. This time counted toward his four-week jail sentence, which he was handed in July. He turned down an offer to serve probation instead.

As soon as he was free, Yee was back at it, posting on YouTube, apparently thriving on his newfound fame, and making increasingly shocking statements — notably, on Twitter, that sex with minors was not necessarily nonconsensual. This brought on more charges, another trial, an appeal, a guilty conviction, a sentence, and six more weeks in prison. He would not yield to the government’s orders; they would not back down despite his lawyers’ pleas.

International human rights organizations have condemned the Singaporean government for its treatment of Yee. Amnesty International “considers him to be a prisoner of conscience, held solely for exercising his right to freedom of expression.” Human Rights Watch wrote that “the Singapore government has subjected Amos Yee to a sustained pattern of persecution, including intimidation, arrest and imprisonment for publicly expressing his views on politics and religion, and severely criticizing the government leaders.”

Dodwell argued that Yee’s age was a factor, too. “For me, when a child is being difficult or saying these things, I wouldn’t accept it,” he says. “But it’s not criminal. He’s been extremely rude and perhaps even vulgar, but it’s not a crime. That’s the angle at which we came at. But regrettably we couldn’t convince the judge.”

By the fall of 2016, Yee was done with his second prison term – four weeks in prison, two under house arrest — and living at home with his mother, whom he fought with and swore at constantly. He’d dropped out of school, traveled some, and had no plans to attend college. He had his heart set on becoming a famous YouTuber.

His legal bills and battles loomed before him. But at least he had the internet. And he’d become a public figure — and loved it. “I wanted to make a mark on the world and get the greatest amount of publicity,” he said.

Left: me blaspheming #Christianity Right: me blaspheming #Islam But all religions r equal right? #ReligionOfPeace

As Yee’s case gained prominence, he found champions and kindred spirits on the other side of the world. It’s not hard to see why internet atheists and free speech advocates of various persuasions were drawn to Yee’s battle: Here was a kid who was unafraid to lay into organized religion in the crudest of terms, and was punished not just by squishy social norms but by an actual repressive government. His case seemed black and white: a perfect vehicle onto which they could unleash their own frustrations with what they saw as a double standard governing who gets to say what, and who’s protected by conventions around free speech.

For Melissa Chen — a 31-year-old Singaporean biologist who came to the US for college and has, over the years, become a relatively prominent figure in the American secular/atheist community — Yee’s story was personal: As a fellow Singaporean who’d attended religious schools, she identified with Yee’s “contrarian, rebellious side.”

“Singapore punishes nonconformists,” Chen told me, sounding almost parental toward Yee. “It’s a very communitarian culture. You acknowledge that some things are better not said or not done of the sake of social harmony and the greater good.”

The two struck up a correspondence on WhatsApp, and during Yee's trials, Chen took to Facebook and Twitter, tweeting with the hashtag #FreeAmosYee and agitating on forums to get his case in the news. Her campaign helped land him a spot on alt-lite darling Dave Rubin’s YouTube show, where he gave an expletive-laden Skype interview about his predicament while his mother did chores in the background.

It was Chen who suggested Yee come to the United States. While asylum laws can’t magically grant Yee the right to express himself back home, they can allow him to relocate, thereby protecting him from any political persecution that may occur as a result of his statements. At first he was ambivalent, but as his trials dragged on, he made a decision. Chen flew to Singapore to meet him at his home while he was under house arrest in October of last year.

“I admire people who are outspoken, even if they are a bit nuts.”

Chen advised Yee to fly in sooner rather than later, to avoid the uncertainty that comes with any presidential transition. She recalls finding Yee to be the vivacious, cerebral kid she expected from YouTube — with a few significant blind spots: “I asked, ‘How are you going to live? How are you going to make money in the US?’ And it didn’t appear to me that he put thought into it.”

Yee had also been corresponding on Facebook with Nina Paley, an animator and artist in Champaign, Illinois. The pair connected when Yee mentioned her work in one of his videos and exchanged messages over the course of several months, discussing copyright, radical feminism, vegetarianism, relationships, the weather.

“I admire people who are outspoken, even if they are a bit nuts,” Paley told me in July. “I liked what he was doing. It made me a little nervous, but I appreciated he was speaking his mind.” Paley said that if he ever came to visit, he could stay with her then-boyfriend, Theodore Gray.

After Chen coached him through the asylum process, Yee then wrote to Paley to ask if her offer still stood, and whether she thought coming to the US was a good idea. “America is where the action is, isn’t it?” he asked. “I would do research but I honestly don’t know where to do it,” he continued. “There isn’t a Youtuber who recommends which countries to migrate to.”

Paley said she did her best to dissuade him. “Everyone I know who can leave the US is doing so,” Paley warned. “If you end up in jail you will be fucked.” But “if you really want to come to the US, where racism is on the rise and there’s no health care for the non-wealthy, Theo’s offer is genuine,” she added.

“I don’t really know what drove him,” Paley told me in July. “It might’ve been romantic ideas about America. He might have seen YouTube videos and interesting things coming out of the US and thought, This is where you can do stuff and speak your mind. Or maybe it was him just being a kid.”

By December, Yee seemed to have made up his mind about coming, and noted that he was dealing with more legal and political pressure at home to stay quiet: “I really do want to criticize Islam, and Muslims are starting to file police reports. Maybe I’ll head to Illinois early,” he wrote in a message to Paley. “How do I get to Illinois? Is there an Illinois airport?”

Paley now regrets having played a role in Yee’s asylum attempt. “I felt terrible when this happened — I wasn’t encouraging him. I was regarding him as an adult,” she added. “But when I go back and read this stuff again, I’m like, wow, he had no idea.”

On Dec. 14, he boarded a flight to China and, after a 14-hour-layover, one to Chicago.

When he landed at O’Hare and found himself face to face with an immigration officer, Yee fumbled. First, he said he was just visiting. Then, the officer confiscated his electronics and found messages he’d exchanged with Chen discussing his asylum claim. That was when he admitted to having other plans: He wanted to become a political asylum-seeker because it was unsafe for him to return home. Because Yee entered on the Visa Waiver Program, he did not have the right to a bond hearing before an immigration judge.

Instead of going home with Theodore Gray, he was sent to the McHenry County Jail in Illinois, where he was detained without any indication of when he’d get out while his claim was processed. Through her contacts at a nonprofit called the Human Rights Foundation, Chen put him in touch with Sandra Grossman, a lawyer with a small practice based in Maryland who agreed to represent Yee pro bono. His lawyers submitted his file in late January.

The timing was awful. Yee arrived in the States just weeks after the election. By the time a judge heard his case, Donald Trump had been sworn in as the 45th president of the United States. Thanks to a change in policy, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) wasn’t granting parole to asylum-seekers in the midst of proceedings. “Maybe under a previous administration, he would have been released on parole or some kind of humanitarian release,” said Chris Keeler, Grossman’s colleague who’s working on the case with her. “But under the current climate our request for parole was denied.”

Still, Yee’s case for asylum seemed promising, because it was easy to prove he’d been persecuted back home. His lawyers found witnesses — including human rights organizations, an opposition leader in Singapore whose family was persecuted for their dissident views, and other Singaporean activists — to testify on his behalf remotely and in writing.

Crucially, they had records of his arrests and incarceration, along with documentation of Singapore’s poor track record regarding free speech and how it has used colonial-era sedition laws to target political opponents. “The big issue in most run-of-the-mill asylum cases is credibility,” Grossman said. “In the case, it’s all documented. Whatever he says is backed up.”

The crux of his asylum case was that his prosecution was, in and of itself, persecution. The lawyers argued that nobody was truly hurt by his anti-Christian and anti-Muslim statements, and that Yee — not a troll but a “social media activist” — had become a target for political reasons: Lee Kuan Yew’s son, Lee Hsien Loong, currently rules the one-party state. They pointed to evidence that members of his political party have made similarly off-color statements against Muslims on social media and gotten off scot-free; the charge that Yee was "wounding religious feeling," in other words, was a pretext for punishing him for celebrating the death of a popular politician. They argued that “Mr. Yee suffered persecution at the hands of the Singaporean government on account of his political opinion and his membership in particular social groups” — meaning atheists — and that Yee qualifies for protection under the UN’s convention against torture and risks being detained and further persecuted if he were to return home.

“If the Immigration Judge’s decision is upheld, it will serve as a symbol of hope to all of the internet bullies and conspiracy theorists throughout the world, that no matter how foul your behavior, the United States will not allow anyone to stop you.”

The Chicago immigration judge assigned to his case, Samuel Cole, agreed with their assessment and granted Yee asylum on March 24, calling Yee a “young political dissident.”

The next day, though, ICE informed Grossman and Keeler that Yee would not be released until the judge’s order was finalized — a minimum of 30 days. “Interestingly, they made the decision not to release him after the judge granted asylum without a pending appeal,” said Keeler. “It’s one of those things where it’s hard to tell if it’s a change of policy due to the change in administration, or if it’s because it’s a high-profile case.”

Four days later, the government formally contested Cole’s judgment, siding with the Singaporean courts by arguing that Yee was breaking legitimate Singaporean laws and had been treated with the appropriate levels of respect in and out of prison. “The immigration judge erred by favoring highly speculative testimony over objective evidence in the record,” they wrote.

Yee, the government said, was targeted for legitimate legal reasons, not political ones, so “the judge’s finding that the applicant’s prosecution was a pretext cannot be sustained.” The government’s counsel called into question Yee’s reliability and the credibility of those testifying on his behalf.

Then, the lawyers argued that letting Yee into the country would set a worrisome precedent. “The applicant’s antisocial behavior ought to give the Board pause before granting a discretionary form of relief as abusive behavior through social media has become a model, technological dilemma, with a subset of bullies known as ‘trolls,’” they wrote.

“If the Immigration Judge’s decision is upheld, it will serve as a symbol of hope to all of the internet bullies and conspiracy theorists throughout the world, that no matter how foul your behavior, the United States will not allow anyone to stop you.”

Yee’s lawyers say the government is missing the point: It’s about political persecution, not free speech. “Amos was persecuted because he criticized the government,” Keeler explained in an email. “Singapore gets to decide what is protected speech and what is not in Singapore. However, as soon as the Singapore government starts using its legitimate speech laws to target political dissidents, the question ceases to be one about the freedom of speech and immediately becomes one of political persecution.”

In early July, I traveled to meet Yee at the Dodge Detention Facility in Juneau, Wisconsin, where he was detained for six months before being transferred to another detention center in Illinois in mid-August. I drove to Juneau with Adam Lowisz, a 33-year-old supporter of Yee’s who’s emerged as a one-man PR firm for the young detainee.

Like Nina Paley and Melissa Chen, Lowisz is a card-carrying secularist and an advocate for free speech. A two-time Obama voter, he now supports Trump, plans to obtain a conceal-carry gun license to protect himself from aggressive antifa agitators, and aspires to help skeptical Muslims leave their religion.

It was through a shared disdain for what they call the “regressive left” — social justice warriors and the like — that Lowisz got in touch with Chen, and when she got too busy to handle Yee’s case, he found himself running the show: coordinating media coverage, posting to Yee’s Facebook account, soliciting donations (many of them have come from Gray), and sending the young prisoner books. So far, Yee has requested several novels by David Foster Wallace, whom he calls an “unparalleled genius”; A People’s History of the United States by Howard Zinn; and several chess manuals by Bobby Fischer.

Lowisz talked constantly as we made our way to Juneau, 60 miles due northwest of Milwaukee. The conversation always seemed to veer back to his dim view of religion, and Islam in particular. That, he said, was what he appreciated most about Donald Trump: He was forcing people to have difficult conversations out in the open.

I pointed out that Yee might not be in this situation had it not been for the Trump administration’s hard line on immigrants, to which Lowisz (whose Catholic grandparents were born in Poland) responded that he was not against all immigration — that people like Yee, who stand for secularism and humanism, should be welcomed to the US. It’s important to stand up for Yee, he says, because the teen stands against “regressive” progressives.

But isn’t Yee a lefty? I asked. “He hates social justice warriors,” Lowisz said. “He even stopped being a vegan!”

At the tidy three-story prison — which, from the outside, could have passed for a community center or a school — Yee greeted us from behind a glass wall, in seemingly good spirits. His hair was shaggy and long, and a faint hint of a mustache had grown in; Lowisz commented that he’d gained a few pounds. “Must be all the snacks,” he remarked. (A few weeks prior, Lowisz had received an email from Theodore Gray complaining that Yee was burning through money at an alarming rate. It turned out that he was spending it all on junk food.)

Though the tinny phone, grinning impishly, Yee talked about chess. “I’m reading Bobby Fischer’s book. I’ve gotten better," he said. "I’m starting to beat people.” He talked about the detention center as though it was an anthropological experience. (“You interact with Mexicans, blacks, lower-class people. I found out how offended they get when you use the [n-word]. They’re really shocked about it!”) He described having befriended a former drug offender who’s facing deportation, which has pushed him to believe in open immigration policy. (Lowisz grimaced.) He’d gotten into an argument with a visiting imam earlier on in the year, too. “I went to hear him speak, because criticizing religion is my job,” he explained. “I told him he was spreading lies.” That, he said, landed him in solitary for two weeks.

Yee struck me as lost. He was clearly capable of expressing complex arguments, but woefully unaware of the challenges that lay ahead in the real world. He spoke of his immigration saga as though it was a bit of an American adventure. Did he miss anything? The internet, he answered. What about his mother? Not really; he never called. (His mother, Mary Toh, declined to be interviewed — “I get stressed talking to the media,” she wrote in a message on WhatsApp — but said, “I’m sad to see my son growing up mostly in jail for the past 3 years.”)

Given what had happened to him in the US, did he even want to stay in a country where he knew so few people, under an administration that locked him up for so long? Yes, he said. “I think I’ll feel really at home,” he added in a phone call the following day. “[Americans] seem open, talkative, they are prone to being more loud and obnoxious and animated. Compared to Singapore, they’re much more adventurous.”

I asked Yee what he thought would happen when he left detention. He shrugged. “I might come out and decide my politics are garbage.” But mostly, he wanted to go online and make more videos, meet girls, eat better food, see the new Spider-Man movie.

Returning to Singapore could be legitimately perilous — Alfred Dodwell said Yee would almost definitely be sent to prison. But at the same time, it’s unclear what he’d do in the States.

“I don’t know if asylum is the way, but I certainly think he’s not suited for Singapore.”

Yee will remain in detention until his case is ruled on a final time; his lawyers have filed a habeas corpus claim, which, as of this writing, has not been accepted. If he stays, Yee will face innumerable challenges: financial, social, cultural — but probably not political. If he goes, he’ll have to deal with all of the above, plus the prospect of continued persecution. Yee’s become an infamous figure back home — hated by some, mocked by others, admired by a few, and pitied by the rest. Even those sympathetic to his cause seem to think that what he needs more than anything is love and support. “I don’t know if asylum is the way, but I certainly think he’s not suited for Singapore,” says Dodwell.

Whatever happens, Yee’s story will serve as a cautionary tale to a generation of children caught between the freedoms of the internet and their conservative, controlling society. You can imagine Yee’s likeness at the Haw Par Villa theme park: an intransigent, internet-obsessed child who would not yield to authority, punished by being forced to cut his long hair, shut his big mouth, and languish in a cell with no phone, no computer, and no stimulation.

In the US, the story of Amos Yee reveals another kind of paradox: one within the government itself. Even though an immigration judge previously approved Yee’s asylum claim, the administration has gone out of its way to deny him protection from what would almost certainly be detention and hardship back home. And these lawyers, who are now working for an administration that was elected in part thanks to foreign teenagers on the internet, are appealing his claim in part because he happens to be a foreign teenager on the internet.

In July, I asked Yee if he considered himself a troll. “I do confess I display similarities to a troll,” he answered. “And I do want attention. But a troll has sadistic pleasures. I want to help humans.” ●