A week and a half before the second season of Raphael Bob-Waksberg's Netflix series BoJack Horseman was set to premiere, the writer-creator was full of hedged satisfaction. "I'm glad I'm going on the record so much being like, 'I am proud of this season,'" he said. "Because I know as soon as it comes out, I'm gonna be like, 'What the fuck did I do? Oh my god, it's a disaster.'"

In BoJack's first 12 episodes, the profoundly sad animated sitcom saw the alienated, sweater-wearing horse at its center (voiced by Will Arnett) floundering and realizing he had to change; Season 2, out July 17, asks, Can we change, or are we doomed to be the people we have always been? "I don't think it's spoiling the end of the season at all to say the answer is 'kind of both?'" Bob-Waksberg said, a reminder that this is not a show for the anti-ambiguity set. The series debuted in August 2014 to both obsessive fans and somewhat mixed reviews — at least two critics suggested the show seemed designed to watch while stoned.

"BoJack is a very Raphael thing," the creator said. "It makes it really hard when people don't like the show, because I can't stand behind and be like, 'Well, the network watered it down,' or 'Well, it's not really me.' No, that's me. If you don't like it, you are saying that I am bad."

He was beginning to understand the famously reclusive J.D. Salinger, who figures prominently in Season 2 and who, after the unqualified success of The Catcher in the Rye, mostly wrote with no intent to publish. "The best thing I ever wrote was a script that never got made," Bob-Waksberg said. "Because it's perfect to me. Because I'll never get to see an actor struggle with saying those lines. I'll never get to screen it for an audience and see how they're not really laughing at it." Success, in other words, is double-edged — much like it is for BoJack's titular horse-man, whose life and career stagnated after, and because of, his '90s sitcom stardom.

Unlike his horse protagonist, Bob-Waksberg isn't incapacitated by his insecurity. "I wouldn't want to make something and lock it in a box where nobody can ever see it" — which is, in fact, what has inadvertently happened to much of his work. He and BoJack's production designer, Lisa Hanawalt, work for a platform at the forefront of the on-demand marketplace, yet they both like the idea of ephemeral art. The high school friends made a web comic together from 2006 to 2008, and were happy to report that their website's domain name recently expired: The comic has all but vanished.

Hanawalt brings a bright aesthetic to their anthropomorphic-animal version of Los Angeles, scanning watercolors into a computer to give BoJack a handmade charm — and capturing an imperfect look in a digital medium. "Even when the animators are taking my sketches and rigging them for animation, they'll purposefully leave in a lot of my wonkiness from my own drawings," Hanawalt said, mentioning the off-kilter diamond mark on BoJack's forehead. "Sometimes eyes are not the same size, or the legs are a different length."

Her own weird humor is key to what Bob-Waksberg called the "air of lunacy" that makes the show watchable: Hanawalt and supervising director Mike Hollingsworth are responsible for the bulk of the strange background jokes in the show, many of which are too detailed to notice without pausing at the exact right moment. It's an exercise in faith, sending a joke out into the void. "The whole time you're doing it, you're like, 'Ahhh, is anyone gonna notice this thing that I'm at the office at 9 p.m. doing?'" Hanawalt said, before explaining that she'll write a whole article for a half-second shot of a computer screen ("I love doing that," she added). She's also a former "crazy horse girl" who sees poetry in drawing a horse as an occupation.

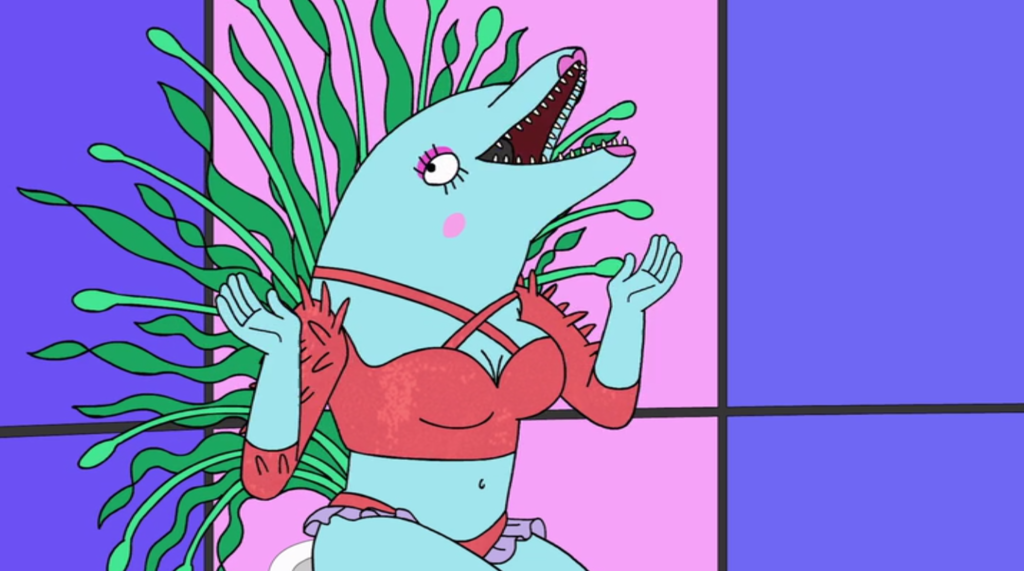

Hanawalt and Bob-Waksberg's working relationship requires a wacky mutual trust. She recalled that he once said to her, "Oh, do you remember that girl who was in our English class senior year of high school? Draw her, but as a dolphin." Hanawalt understood — "bubbly and sexual in a way that's precocious for how young she is" — and drew Sextina Aquafina.

Although BoJack was inspired by one of Hanawalt's horse illustrations, when Bob-Waksberg initially approached her about the project, she was hesitant. "I was like, 'Eh, this sounds too dark, I don't like it,'" she said. She has changed her mind, although, tellingly, BoJack's bright and good-natured dog nemesis Mr. Peanutbutter (Paul F. Tompkins) is her favorite character.

According to Bob-Waksberg, Mr. Peanutbutter has a base happiness level that is higher than average. "Some people are just genuinely happier than other people, and they always will be, and it drives me crazy," he said. "I see why BoJack hates him."

BoJack hates him for several reasons: Mr. Peanutbutter starred on a sitcom with the same premise as BoJack's, and he is now married to Diane (Alison Brie), whom BoJack fell in love with in Season 1. Following regular sitcom logic, Diane and BoJack are perfect for each other: She's a thoughtful, relatively together writer who has published multiple books, and he's a tortured, middle-aged narcissist with a drinking problem. But through the irregular and painful sitcom logic of BoJack Horseman, our hero doesn't get the girl; moreover, his bizarre courtship and subsequent hurt feelings push her away.

"We're trained by TV shows and movies to think there are two kinds of relationships," Bob-Waksberg said. "There's the guy that you're supposed to be with, and there's the guy you're not supposed to be with. But I think, in truth, you never really know." He himself has never really known — "yes, for now" is as much as a person can ever say to another person, he said, now-married Diane included. "Yes, for now" extends to her career as well: Diane's ambivalence about her choices pervades her whole life, and includes angst over a job offer to write in a war zone. Of the character's diffuse uncertainty, Hanawalt said, "I relate to Diane about that more than anything else. 'Ehh, which job should I do? Should I stay or should I go? Am I with the right person?'"

The characters' misgivings often come directly from the show's creator. "I'm very interested in these people who say, 'Yes, I know I'm gonna spend the rest of my life with this person.'" Bob-Waksberg said. "I kinda don't buy it, but I don't think they're lying, either. I think some people are lying. I think some people are lying to themselves." This is something BoJack reckons with in the second season, when he dates a charming owl voiced by Lisa Kudrow.

The dearth of clear answers is in the fabric of the show: Sunny Mr. Peanutbutter can be underhanded, BoJack is frequently terrible, and even Diane — who initially seems like the archetypical levelheaded girl who'll save the male protagonist with her good sense and kind heart — gets to be a hypocritical dick. "I don't need a character to be good, or do good things, to be likable," Bob-Waksberg said. "You like characters for a lot of reasons. It doesn't always mean it's someone you would be friends with in real life, or someone that you respect. I'm always more interested in, is this character human? Do I understand where this character is coming from, why this character's behaving the way they are?"

To create those characters, Bob-Waksberg has made a point of assembling a gender-balanced writers room. "I know some writers, when they put a room together, they're really looking for who's best gonna capture my voice? Like eight little mini-mes," he said. Seeking out a variety of voices has been crucial to the quality of the show. Bob-Waksberg asks each writer he meets with to name their favorite character. One writer chose Diane, who is "nobody's favorite." He hired her, and Joanna Calo has written a Diane-centric episode this season he's very excited about.

The gender balance is also critical to the jokes themselves. "Vera [Santamaria], one of our writers, pitched this joke, and I remember all of the women in the room laughed, and none of the men did," Bob-Waksberg said. (Princess Carolyn shows up late to a meeting. She's harried, with a gravy stain on her clothes and a broken heel, and her boss tells her to clean herself up because she looks "like a woman from an '80s deodorant commercial.") "What was really interesting to me is thinking about all the times a man had pitched a joke and all the men had laughed and none of the women had, and I didn't even notice. I'm sure that happened a ton."

Last season, the show introduced a female director character, Kelsey Jannings (Maria Bamford), a commanding lesbian who enters BoJack's life in part because Bob-Waksberg wanted BoJack to have a relationship with a woman that had no romantic tension. This season, although her arc is not about being a woman, the show sneaks in a line about how the big-budget movie she's directing is the one shot she'll get, and if she doesn't do a perfect job she'll be relegated to indie movies. It's funny because it's true; as Hanawalt put it, "There's too much put on the fact that there's one female director and if she fails it's like, 'Never again.'" (In 2014, women were half of the humans and only 7% of the major feature directors.) Kelsey, who, for the most part, is a tough, no-nonsense woman, is allowed a moment of vulnerability with the realization that she may have to go back to directing movies about lesbians teaching other lesbians to recycle.

These characters can be vulnerable because the writers allow themselves to be vulnerable too. Last season, a writer poured his heart out in a letter to Cameron Crowe, but Crowe still said he was too busy to voice Cameron Crowe the raven. (The raven mostly escaped the fate of some other real-world BoJack parts — according to Bob-Waksberg, the characters get a lot meaner when the actor namesake doesn't want to play them: Notably, the last time we saw the cartoon version of Andrew Garfield, he had broken every bone in his body after falling into a hole.)

While the show seems cynical — and thus out of step with the tendency toward the warm fuzzies — it functions, really, through naked sincerity. "You assume that this is very personal to me, nobody else could possibly love this," Bob-Waksberg said. "You throw it out over a canyon, and then the hope is that maybe someone on the other side of that canyon will catch it and will be like, 'Oh, me too.' And that's why you do it. Here it is, folks. That's where we find our heroes today, with a ball halfway thrown across a canyon."

"Deeply insecure," Hanawalt said. And indeed, toward the end of the interview, Bob-Waksberg turned to the reporter and asked, "Did you like it? You can be honest. No, you can't, who am I kidding? What if you were like, 'Actually, no. Thanks for the interview; it really doesn't work as a TV show.'" He smiled but did not laugh at his joke.

Only 7% of major feature directors in 2014 were women. An earlier version of this story overstated the percentage.