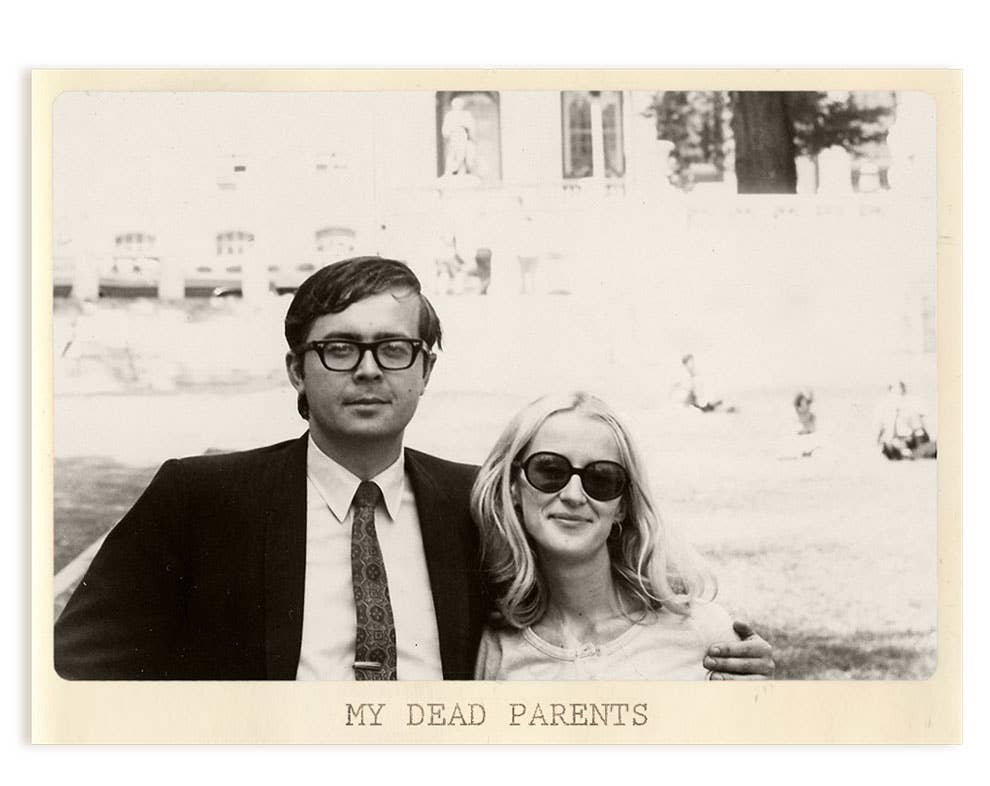

In 1994, when I was 16 and he was 54, my father George was killed in a car accident in Ukraine. He'd begun working in Ukraine, where he was born, after Communism fell, something that he didn't think would ever happen in his lifetime. He considered helping his homeland an honor and an obligation, so after a long career in international banking in the Middle East and Africa, he happily went "home" to set up the country's first central bank and then stayed to work as a venture capitalist. He'd spend roughly four to six weeks in Ukraine at a time before returning to his other home in Boston, where my mother, my sister, and I lived, in a brick townhouse on a quiet street near the Charles River. He hoped that sooner rather than later, he'd be able to run his operations from Boston so he could be with us, but those plans were cut short. Late one night, when he was being driven home from the Kiev airport, his driver was blinded by a truck speeding toward them in the same lane. His driver lost control of the car, swerved into the truck, and my father and the other passengers died instantly.

Back in Boston, there was an early morning knock on the door. I answered instead of my mother, Anita, because it was a Sunday, and I thought that perhaps some friends needed to crash after clubbing. I opened the door to find my father's boss, stricken and pale. As I blinked into the sun and my mother hovered above us in the shadows at the top of the stairs, he unceremoniously announced that my father was dead.

My mother went back to bed immediately, and it was only when my sister Alexandra, who was working in Ukraine that summer despite the fact that she didn't speak any Ukrainian, called a bit later, that my mother began to comprehend what happened. She begged my sister to say that the news wasn't true. But my sister couldn't. She'd just had to identify my father's bruised and bloated body in an un-air-conditioned morgue outside of Kiev and deal with a flood of people and paperwork she couldn't understand. She also had to deal with the rumors that immediately started, as did all of us, that the accident wasn't an accident at all, but was something carefully planned by someone who didn't like what my father was doing. That my father was actually murdered was, and remains, a strong possibility, one that many people believe to be fact — that's just how business was done in Ukraine in the '90s.

As my mother systematically crumpled and wailed, and as our house filled with neighbors and muffins that no one would eat, I walked to Starbucks by myself and got a coffee, then took my time getting home.

I'd had a difficult relationship with my father, and I instantly felt that his death was a gift, just as I'd quickly relished his absence when he began working abroad when I was 12. The weeks he was gone were the weeks that I relaxed because I knew I wouldn't be screamed at, and when I learned that he was dead, I sensed that a lifetime without him could only mean more of the same. As I watched everyone else's grief unfold around me, I couldn't help but be a little ashamed and embarrassed by the fact that I not only wasn't sad, but felt, more than anything, a sense of freedom.

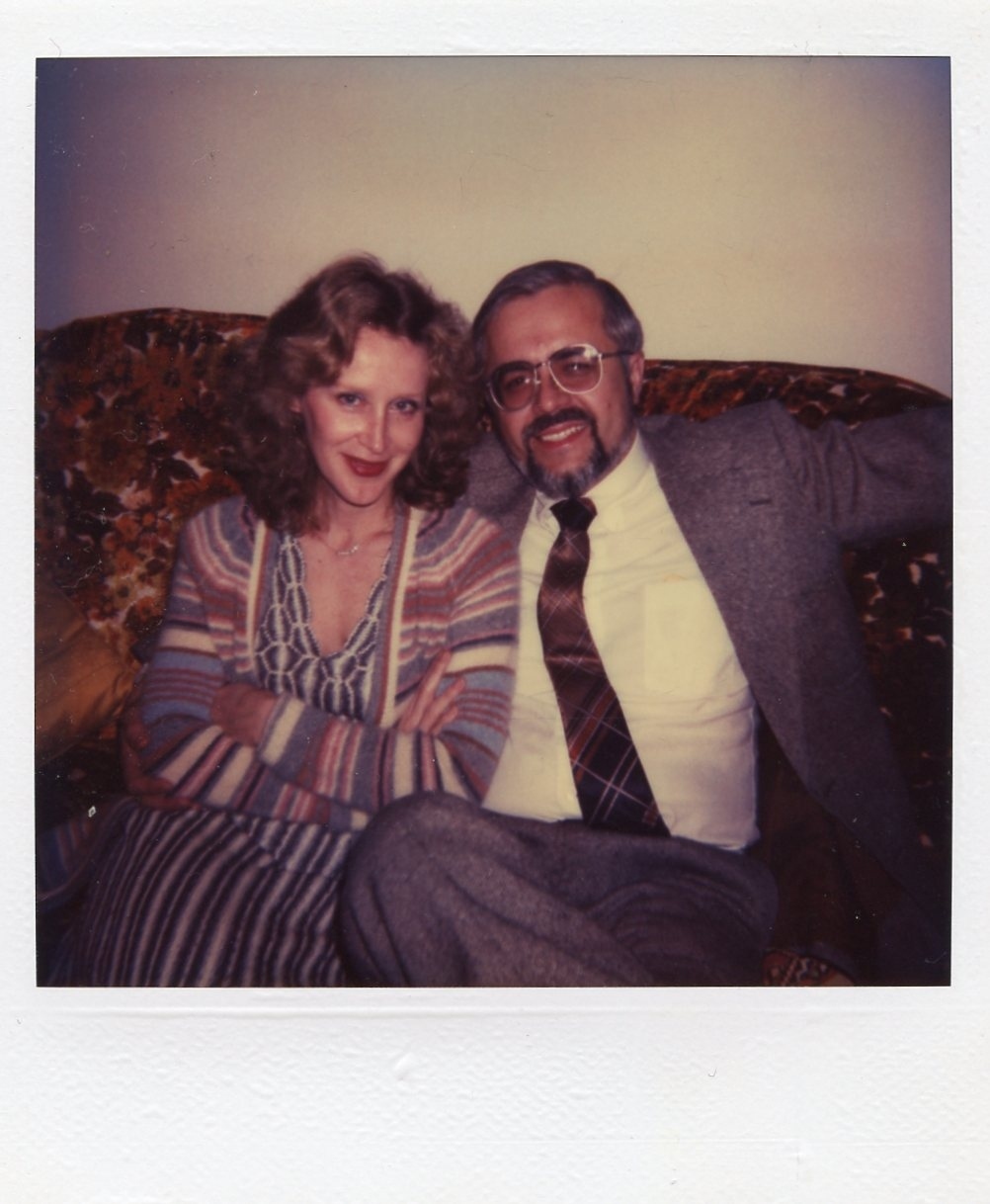

Sixteen years after my father died, when I was 32, my mother died in her sleep. She was 64. The official cause of death was heart failure, but really, what she'd died from was unabashed alcoholism, the kind where you drink whatever you can get your hands on, where you're often so drunk you shit in your bed or on the floor, and you cause so much brain damage that you permanently lose the ability to walk unsupported.

Like my father's death, my mother's was a relief, though for different reasons. My mother had been slowly, and dramatically, as was her nature, killing herself for years. She'd always been a drinker, but she really committed to it after my dad died. His death either caused such a serious depression that she had to self-medicate to the point of oblivion, or it gave her the permission she'd been waiting for to throw everything away.

My father died while I was in the middle of high school, and by the end of my senior year, my mother was drinking hard. In college, she was calling me as I boarded the bus home for Thanksgiving to warn me that she was wasted, and after finding her slumped over a chair in our dark kitchen, I would have to rope my poor ex-boyfriend into helping me get her to the emergency room. Over the following years she only got worse, despite multiple trips to detox, five weeks at Betty Ford, and almost one year of sobriety. She was once visiting an old professor friend at Tufts, and she got so drunk and wild that he had to call the campus police to get rid of her — and to get back at him, she stripped naked so the police would "really have something to see." She showed up to visit me in California with a face so bruised from an accident she didn't remember having that multiple people asked if she'd just had brain surgery. She had me in a constant state of anxiety; I always worried that she was going to fall down the stairs, die helplessly, and not be found for weeks. My sister and I eventually hired home health-care workers to look after her a few days a week, which was good for all of us, but many of them quit because taking care of her was just too depressing.

After my mother died, people always wanted to know how I was doing, and I always said that I wasn't sad for myself, but that I was so, so sad for her. I was, and am, sad for her — sad that she went from being an intelligent, successful, and charismatic woman to someone who drank so much that she often shit on the floor. But was I sad that my mother, who drank so much that she often shit on the floor, was now gone? Not really. I was 16 years older, but I was right back to where I was when my father died. I felt the exact same way, and I didn't feel the exact same things.

In the weeks following my mother's death, my friends, some of whom had been around for my dad's death as well, came over to my Brooklyn apartment one by one to make me dinner on the nights my boyfriend was working late, I guess because I wasn't supposed to be able to feed myself. They would come and cook and look at me with probing eyes and open arms, ready for me to say or do whatever I needed — but all I could do was scarf down their sautéed cod and stare back and think, Why aren't I as sad as I'm supposed to be?

I didn't know how to handle people's expectations of my grief, and soon I developed a sense of defiance, a pride in my lack of sorrow and in my ability to just keep going. Both of my parents were dead now, and I was fine. Everyone who had parents seemed like pussies by default, and people who'd lost parents and were really sad about it? They were pussies too.

In the months after my mother died, I was tasked with cleaning out her house, my childhood home, which had always been a cramped testament to my parents' wanderlust and curiosity. There was no television in our living room, but there was an African statue or mask in every corner, Iranian kilims, Indonesian textiles, Japanese kimonos hanging off every wall, and shelves that literally overflowed with art books and foreign trinkets. People often wandered through our house with their mouths hanging open, examining every sword, carved horn, or meditation bowl they could reach.

When my father died, our home started dying as well, and by the time my mother passed away, the treasured rugs were being eaten by moths and mice, the fire escape was dangling off the back of the house, and some windows wouldn't open while others wouldn't close. Everything that once seemed special was chipped and cracked, buried under a sticky coat of dust.

I began my work in my mother's study, which had become a haphazard storage room for everything from mismatched shoes to years of unopened mail. I spent days bagging sweaters for Goodwill and organizing the incredible amount of clip-on earrings and pantyhose she'd purchased from Filene's Basement decades before and never worn. I'd anticipated this chore for years, and though it was surreal to finally be doing it, it was also calming.

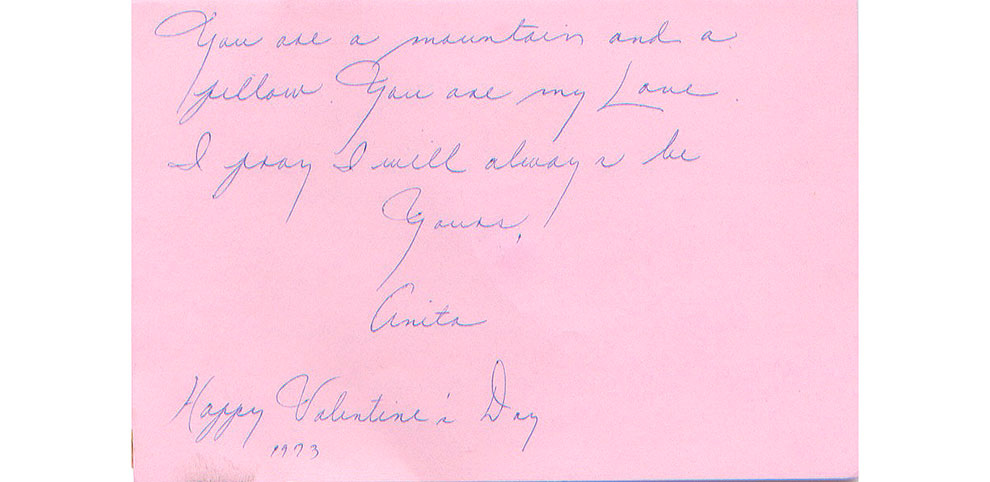

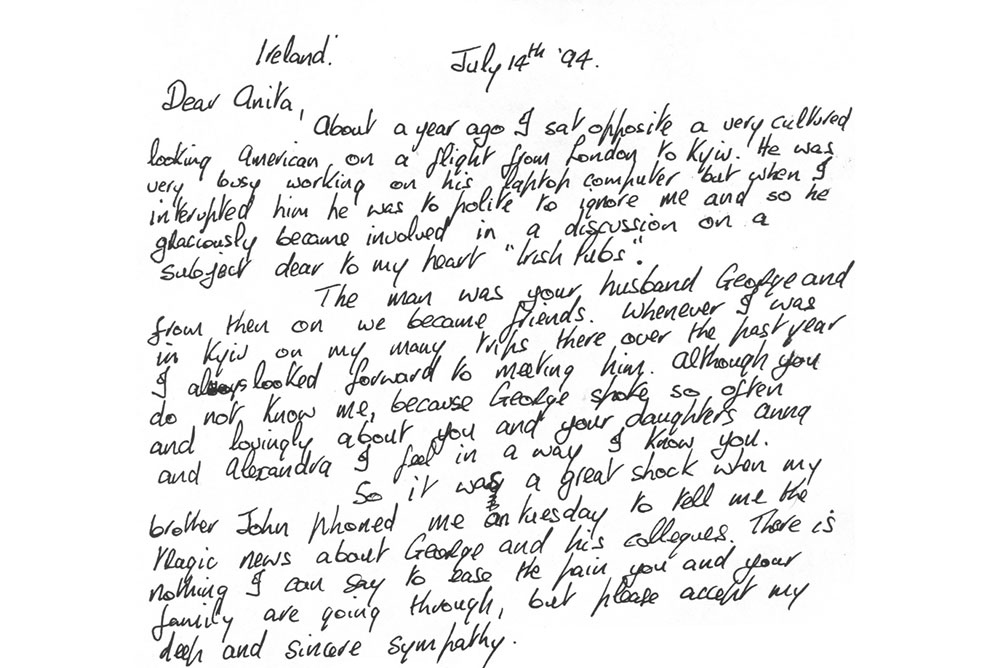

Once I moved beyond her clothes and crappy jewelry, I got into her more personal belongings, her file cabinets, battered shoe boxes stuffed with papers, and trunks full of undated slides and photographs that my father, an accomplished photographer, left behind years ago. This was quiet, intimate territory, and I didn't know how to approach or navigate it. I certainly wasn't prepared for what I would soon discover: that in the bundles of faded telegrams, handwritten love letters, old faxes, and diaries abandoned after only a few pages, my mother had left me a window into both of my parents and their complicated marriage. Even a superficial scan of these artifacts revealed that my parents had an entirely different relationship than I'd assumed, and were, in many ways, profoundly different people than I'd long ago decided they were.

For days I sat in my mother's filthy study, surrounded by the relics of my parents' love, trying to take in their lives and thinking, I don't know these people at all. And for the first time, I wanted to.

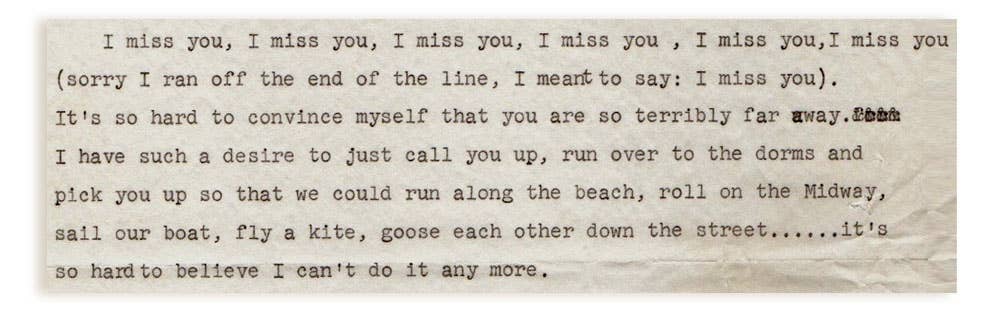

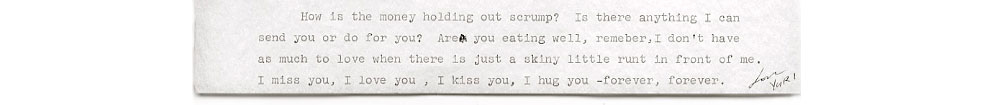

I packed a box of the juiciest things I could find and brought it back with me to Brooklyn. I sat in my apartment and read the letters my father wrote to my mother over 40 years ago, and I imagined him hunched over his typewriter, sweating over his words, and thought of how special it must have felt for her to receive those letters from hundreds and often thousands of miles away, and then going to her own typewriter and writing him back. It was strange to hold things that they'd both held, delicate, wrinkled pieces of paper where they chronicled their love and adventures before sending them off so they could be connected even when they were across the world.

As I began to excavate their lives and search for what was hidden within everything they'd left behind, it was impossible not to think of how easy it would be for someone to piece together my life — all they'd need to do is hack my email. They'd have instant access to my hopes, my loves, my frustrations, every event chronicled in detail to my friends. There would be no mysteries, nothing to explore that I hadn't explored myself and articulated five different ways to five different people. It would be an easy task, and probably a boring one, and there wouldn't be anything to actually touch or hold.

Going through my parents' stuff didn't make me suddenly miss them, but I became more intrigued by them every day. I wanted to know more and more about them, to solve their mysteries. At the same time, I felt a corresponding, if conflicting, urge to speak, or write, about what many people seemed to think was unspeakable: my ever-present lack of grief. So I decided to combine these seemingly divergent impulses into an Tumblr blog called My Dead Parents, which I kept anonymous both out of respect for my family and because, after years of writing fiction, I wasn't sure if I could handle revealing so much about myself in writing. I didn't have a nonfiction writer's courage to publicly own my feelings and experiences, even though I knew, or hoped, they were important.

When I began My Dead Parents, I thought my biggest struggle would be the availability of information, because there were only so many letters, photographs, and memories. But actually, I was lucky to have as much as I did, so that wasn't the problem, not remotely. The problem was what I was doing with all the information I had.

I knew, or thought I knew, that if I wanted to understand my mother and father, to know them as I probably never could have in life, I actually had to be open to learning new things about them, to seeing them from a completely different perspective — how they saw themselves, how others saw them, or simply taking them in through their words or pictures without reading my narrative into whatever was sitting in my lap. I quickly realized that I was deeply welded to my ideas about them and their roles in my life. Whenever I encountered information that contradicted what I'd already decided was the truth, my brain hardened. Every cell in my body said, "Nope." So in the beginning, I would post some of their letters and photos, which was and remains one of my favorite parts of the project, but mostly what I did was talk about myself and my experience of my parents: that my parents were always unhappy, my father was mean, they fucked me up. I talked about me. But what I was really doing was defending the story I'd arrived with against mounting counter-evidence — and losing.

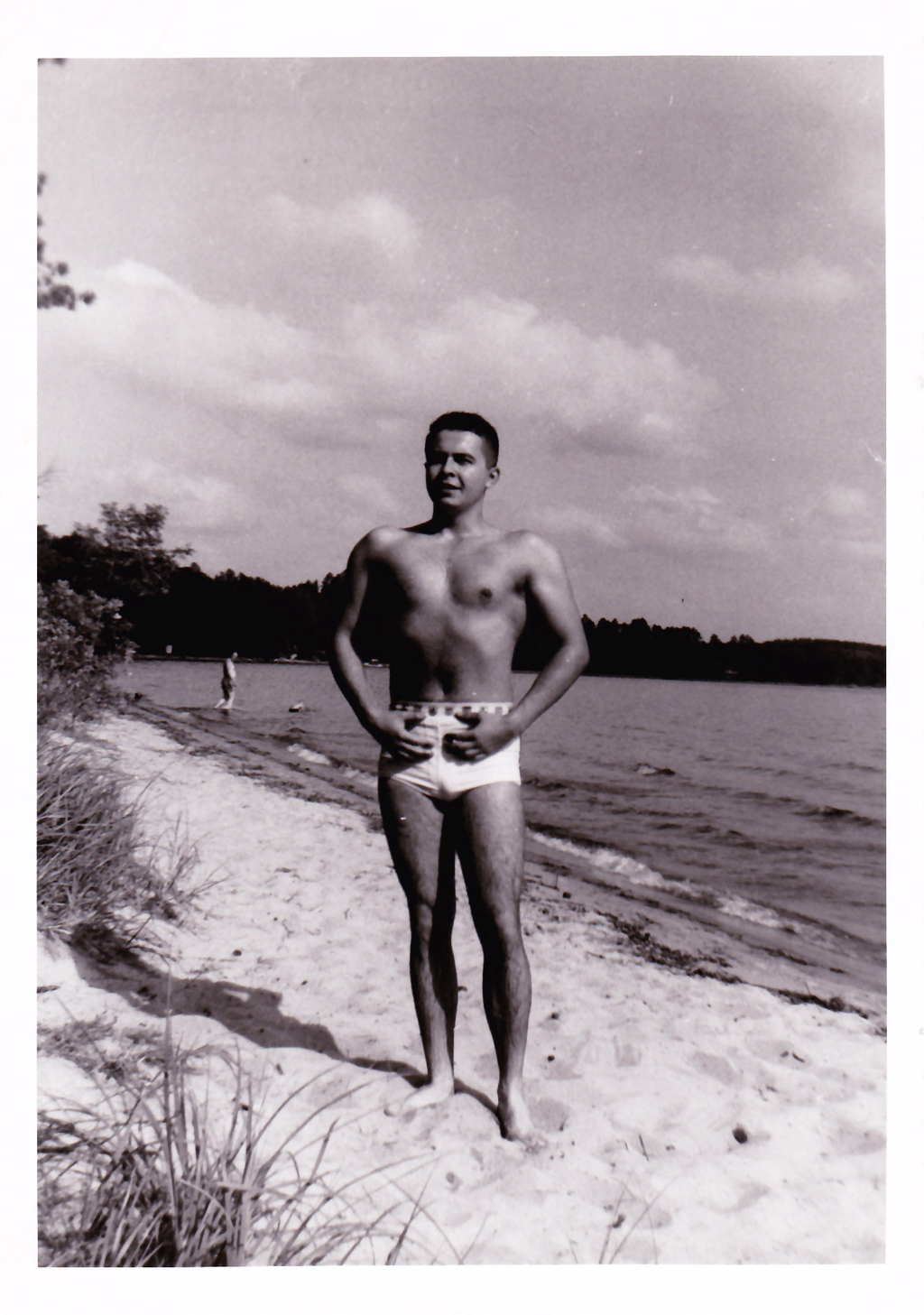

The story was, my father was a successful, erudite, and occasionally hilarious man who prioritized my education and made sure that I grew up more curious and knowledgeable about the world than most of my peers, but he was also emotionally abusive and withholding. I was always, always doing something wrong — I wasn't quick enough, was messy, spacey, and clumsy. He would scream at me about anything, though a favorite trigger and topic was my underwhelming performance in school, which was the result of learning disabilities. He had always been an overachiever, the dutiful immigrant son who was the president of his high school and many of its clubs, who got into Harvard, received two graduate degrees, and whose mind seemed capable of doing everything. That mine could barely do anything infuriated him, and as I struggled with my homework at our long dining room table, he'd stand with his arms crossed and yell that I was stupid, and when my tears started to land on whatever paper of long-division problems or penmanship exercises I was hunched over, he'd call me a crybaby.

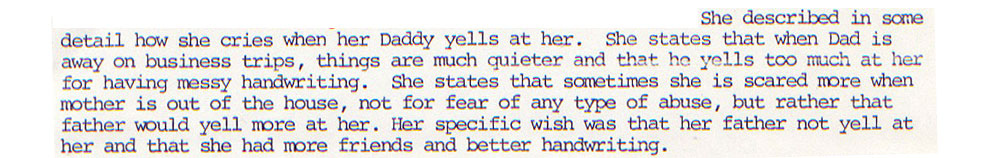

Though my family was comfortable financially, the things that I needed more than anything — compassion, security, unconditional love — weren't available, and that led to my growing up into a kid who cowered out of constant fear of getting in trouble and acted out to ensure she'd get in trouble anyway. In fourth grade, I wrote "I hate me" on the white bathroom wall of my school, and my teacher, who recognized my terrible handwriting, brought me in to discuss it. All it took was her pointing at that sad little bleat of a sentence for me to collapse in tears and to get me into therapy.

In the psychoeducational evaluation that followed — the first of many I'd have over the next few years — the doctor wrote:

It was difficult to discover those lines hidden in that 10-page evaluation, to confront such a clear articulation of my unhappiness as a child more than 20 years later. I was scared when my mom was gone, and I would cling to her before she left for business trips. Though I hid behind her, she was never able to really protect me from my father, and I resented her for that, and for not being able to change his behavior.

I had no idea what to make of my mother when I was younger. She had a successful career in environmental policy with The Sierra Club, and then spent years happily working as an ESL teacher. She stood out in our conservative neighborhood with her messy blonde hair, collection of ethnic jewelry and clothing that included a Chinese motorcycle jacket with a dragon emblazed on the back, and with the cigarettes that always dangled from her mouth or hand. She was a character and a performer. She was always laughing loudly and was ready on cue to roll her eyes or hug me tightly. I was aware that she could turn herself "on" from a young age, because when she was at home, a cloud of unhappiness often hung around her; even when she was with people, I could sometimes see loneliness in the creases of her face when she glanced away or the light shifted.

Because I didn't like my father, I blamed him for her unhappiness. All he seemed to do was reinforce it. My mother needed attention and affection like other people need air, but my father always seemed too busy, uninterested, or distracted to give her what she so clearly wanted. She was always talking to him with need or frustration in her voice as he frowned and leafed through whatever stack of papers he brought home. The more attention she seemed to want, the less he seemed to want to give it to her, and often her sentences would trail off with a weak, exasperated, "George!" As I grew older and more aware of their dynamic, I saw her grow more and more unhappy. At some point I assumed they no longer loved each other, and perhaps never had.

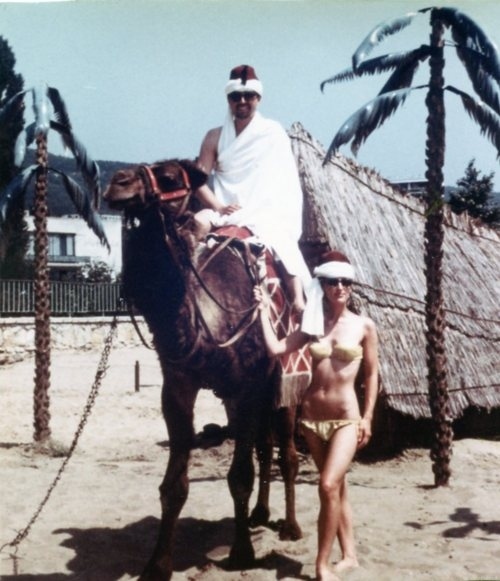

Though I perceived him as treating her poorly, she'd in a sense gotten lucky with my father, whose work took them around the world. She'd once told me that, by marrying my father, she married the man she wanted to be. She'd applied for a job at the United Nations after college, but at that time they were only hiring women as secretaries and translators, and that wasn't good enough for her. Being with my father, who loved travel for travel's sake and also had a job that required he take long international trips, meant that she could go to places like Nigeria and Kuwait with him before getting a job that allowed her to travel on her own.

She loved traveling with my father, but once my parents had kids, she had to stay home and take care of us more often than not. When my father started working in Ukraine and was gone for long stretches of time, she felt abandoned, like he'd left her for the country, even though she understood why he felt he had to do it. She resented his absence and the fact that she was stuck alone with me, an angry, slutty-goth-lite teenager who was barely scraping by in school and refused to listen to anything she said.

In the same psychological evaluation, the therapist noted there was "…some concern on father's part that mother might drink too much. It is reported that she drinks one to three hard drinks per night, but it is stated that this does not interfere with her overall functioning." Everyone knew my mother loved a gin and tonic — even I did when I was 5 — but I was extremely surprised discover that my father was worried about her drinking back then; trying to figure out when my mother really took to drinking has been a mystery my remaining family members have been trying to solve for years. Mentioning her drinking to the therapist meant he was aware, probably before anyone else, of the behavior that would eventually do her in, and I'll never know if he ever tried to do anything about it or if he had any sense of the person she was capable of becoming, and became.

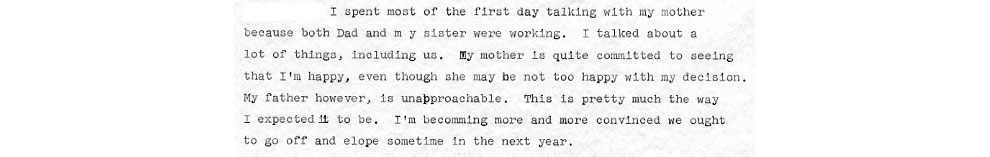

In the summer of 1966, my mother was studying in Austria on a college travel grant, and my father was stuck at home in Minnesota trying to get his parents on board with their engagement. They'd met two years before at the University of Chicago, where my mother was an undergraduate and my father was getting his JD and MBA. I don't know how my middle-class grandparents felt about my mother being 20 and poor, but I do know that they were livid that she was Polish and not Ukrainian. Poles and Ukrainians had never really gotten along, but my young father and his parents escaped Ukraine under the threat of death by Polish insurgents, who'd killed plenty of their friends, and it seemed my grandparents weren't ready to let that go. So while my mother was exploring Europe, my father was trying to make progress with his parents — and writing her letters constantly.

My parents did not elope; they got married on April 8, 1967, in a small chapel on the University of Chicago campus. My father's parents did not attend the ceremony, though they eventually showed up at the reception. My mother told me my grandparents hadn't supported their marriage, and it was obvious even to me that they never warmed up to her. Because the situation had so clearly pained and annoyed her, I'd only ever considered it from my mother's perspective. I never thought about what it meant for my father to go against his parents' wishes. Marrying her was a significant act of defiance.

As I worked on my blog, I read these and similar letters again and again, and wondered how the man I thought my father was could have written these words, words that are so romantic that I melt on my mother's behalf when I read them. How could my father have been the person that I knew, the person I was happy to have dead, and the person in these letters, a person who was articulate, generous, and so, so loving? And how could my mother, who never seemed very happy with him, love him so much in return? Didn't she know he was a monster?

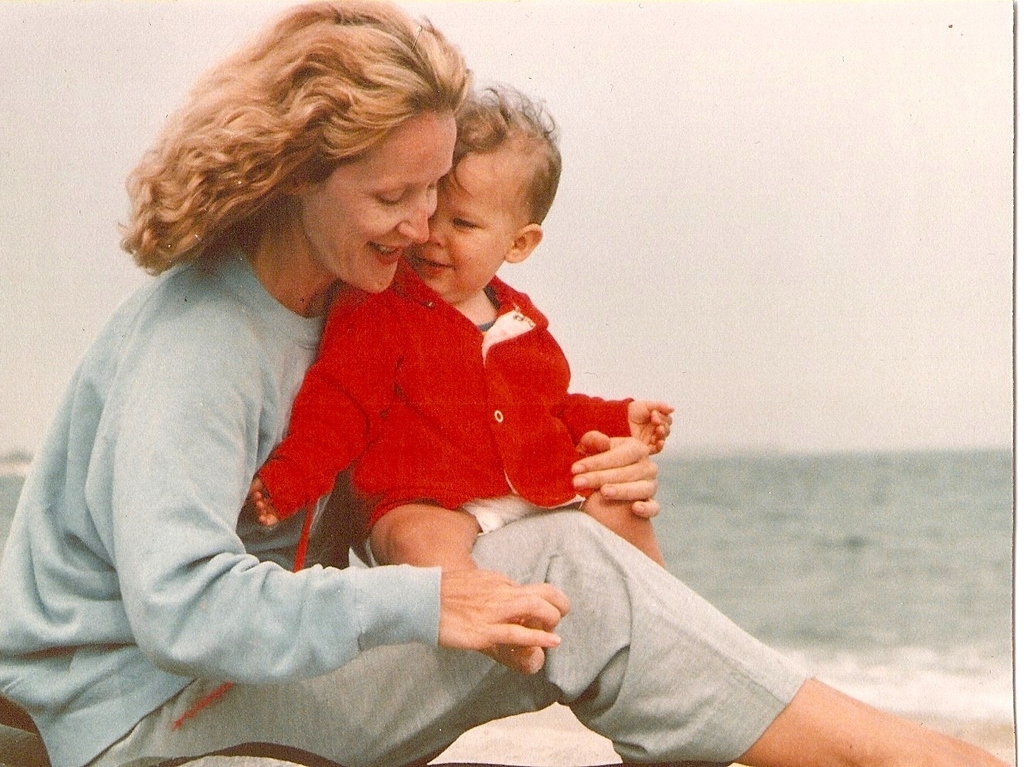

I'd always thought my mother wasn't happy with her role as a mom or wife. I remember random moments where she just seemed annoyed to find me there. I have clear and consistent memories, from when I was older, of her resisting, and even resenting, things that, at the time, seemed fundamental to being a mom, like cooking dinner. I ate a lot of eggs in middle school and high school. I still do. Decades of this sort of seemingly irresponsible behavior led me to believe that my mom simply had kids because she was expected to, and never actually wanted to be responsible for them.

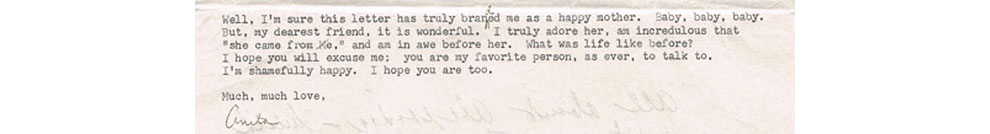

But, as I learned from letters that my mother wrote her childhood best friend Sylvia (which Sylvia gave me at my mother's funeral), my mother was thrilled to become a mom. In 1972, when my parents were living in London for my father's job and my sister was 2 months old, my mother finished off a lengthy letter by saying:

Letters like these continued for two years. When my sister was around a year old, my mother proudly told Sylvia in an undated letter about taking my sister to Geneva to visit her friends and how they referred to her as "that great baby," and said, "I'm still ecstatic over Alexandra, who enchants and delights me to no end. Wish you could meet her."

She loved my sister and didn't ever seem to tire of taking care of her. However, things changed with the birth of my brother Yuri two years later — in small ways at first, and then significantly. My parents were still living in London, and my mother wrote Sylvia that for a while, she "wasn't really sure I liked having two kids. All of a sudden life becomes much more complicated…I suppose one can never relieve the super high of a first thrilling experience although childbirth and the delivery was certainly again enthralling."

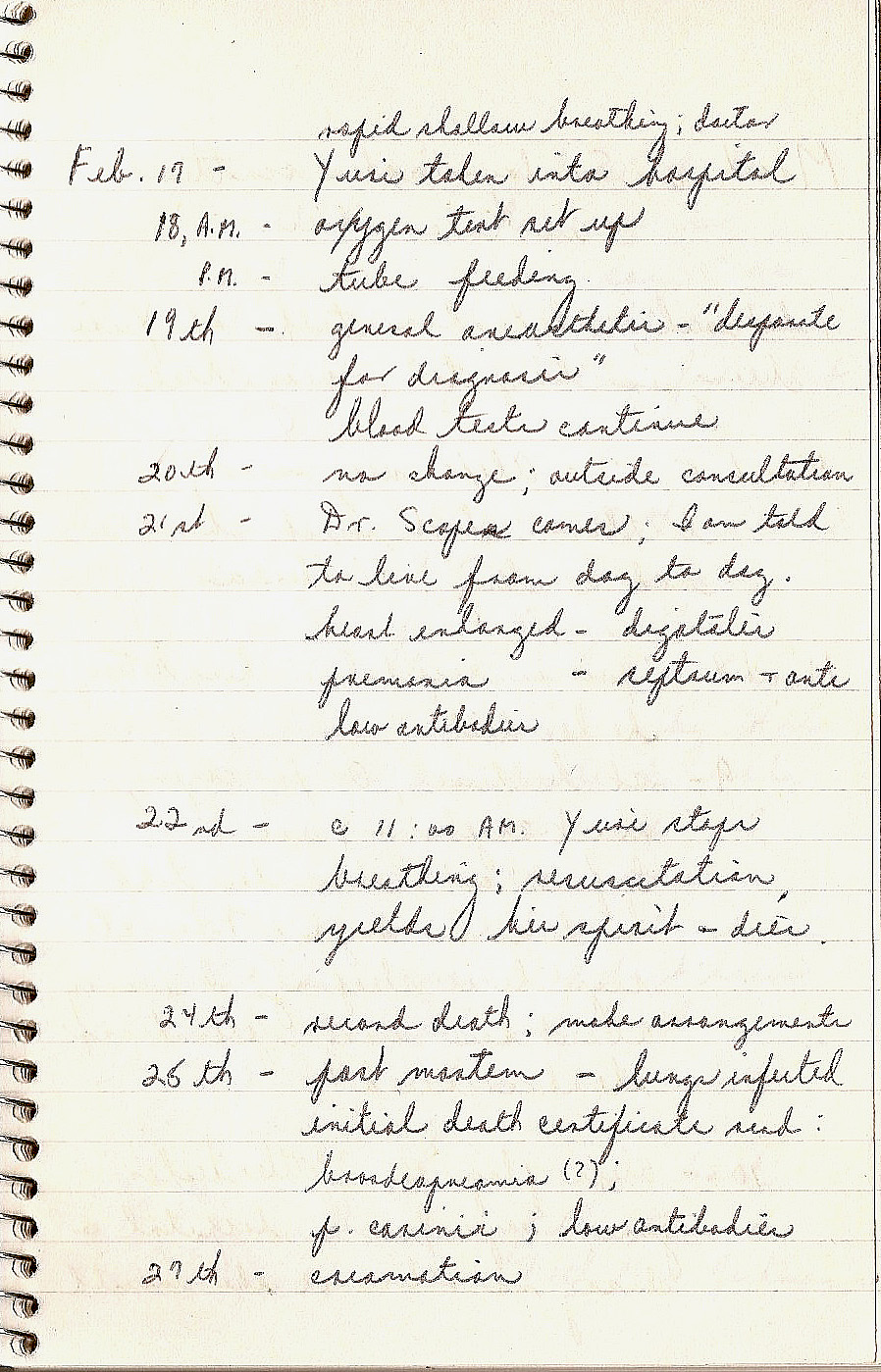

My mother was both overwhelmed and underwhelmed by her second child, and he seemed to break the joyful spell cast by my sister. She was still struggling with her increased responsibility when in the winter of 1975, things quickly turned tragic. From my mother's journal:

March 13 – Last night I lay in bed trying to fall asleep and I wondered with great pain what little Yuri must have thought those last horrible days and those moments he was dying. It breaks my heart to consider he saw only strange faces leaning on his chest, trying to resituate him. How I pleaded for them to let me come in — perhaps if he could have seen his mother, however cloudily — heard my voice. But in reality he was alone in his last moments. What must have been going on in his mind.

Early April — Alexa must have dreamed about Yuri or remember the last time she saw him in the hospital. She said, "Yuri…I buried him and said be better." I really believe I could protect him always. Am answering all the letters and cards which were sent. It's more than awful.

I learned about Yuri when I was 11. A childhood friend told me that I had a brother who died, and she continued to mention it for months. How did she know this? My mother had confided in her mother about it after a PTA meeting, and her mother — who was, confoundingly enough, a therapist and a psychology professor — told her. One day I was sitting in my sister's room and joking with my mother, sister, and grandmother, I think about an AT+T commercial, and I turned to my mother and said, "Did I have a brother?"

My grandmother and sister left the room, and my mother gently told me yes. We went down to my parents' bedroom and looked at pictures of Yuri, and we cried. My mother told me why she'd never told me about Yuri; she said I was her "miracle baby"; she had a lot of trouble conceiving after Yuri died and thought she wouldn't be able to have another child. When I finally came along, she didn't want me to feel like a replacement or that I had something to live up to.

Though I was young when I first learned about Yuri, I remember that my mother told me that she and my father grieved at different times and in different ways, and this letter shows how isolated she was — and how destructive my parents' communication had become. She was so "troubled" by the idea that one of her decisions contributed to her son's death, but she didn't want my father to know that she was thinking such things. What an awful feeling to be alone with. Why didn't she tell him? Was she worried that my father hadn't wondered about the penicillin, and that if she suggested it, he would suddenly blame her for his son's death?

Reading my mother's letters and journals, I realized I'd spent my childhood navigating complex emotions I couldn't have fathomed, and I received a lot of information about sadness, disappointment, and fear that I just couldn't understand. (Speaking of things I didn't, and don't, understand, I went to see a shaman while I was working on the blog, and during a traditional healing ceremony, he asked me if I had a brother. Surprised, I said yes, technically, but that he'd died before I was born. The shaman said Yuri was hovering next to me, and that he'd been with me all my life, messing with me because he was mad that I was alive and he wasn't. It was a crazy experience, but I suppose it's exactly what's supposed to happen when you go to a shaman, or hope will happen when you are so confused about your life that you're compelled to visit a shaman in New York. You should read about it.)

Now when I think about my father yelling at me, I have to wonder if he was actually exorcising his rage at losing a child, his grief, his frustration that first son had to be taken away, and that he wasn't given another. My father was tough on my sister, too — he was a tough Ukrainian dad — but I received the brunt of his anger by far. I was the child who replaced his son, a hyperactive, hypersensitive girl who he just could not understand. Reading my father's love letters to my mother was so confusing, because they felt like they were written by a different man. Now I know that they were. They were written by a man I could never know, a man who was possibly murdered. It probably sounds insane, but that's something that I'm really only beginning to think about now, because for so long I was relieved that he was gone, and didn't let myself care about the how or why.

I'm trying to figure out how I can reconcile all of this new information and turn it into something I can observe and understand, something that can possibly function as an explanation or antidote to my experience. And I wonder, is it really possible, or wise, to let the things I didn't know about my parents, or images I never had, overshadow the ones I did? That seems like a form of magical thinking to me, one that's seductive but also a little dangerous. Is accepting this new story a denial of my own? Or is a refusal the ultimate — and an immature — act of disrespect?

Not only will I never know the man my father was before my brother died, I'll also never know who he was when I wasn't around, when he wasn't being my father, and I'll never know my mother that way either. As I went through more my of mother's files, I discovered correspondence from other people that was much more recent than the love letters I'd been poring over, and was in many ways, more relevant, illuminating, and undeniable. My mother had an entire box of letters she received after my father died, some from coworkers of his that she knew well and many that she didn't, and some from people she didn't know at all. These documents round him out as a person and made him much more relatable — he loved beer, loved hosting, loved talking to strangers — whether or not I want them to.

Because My Dead Parents was a secret, one that I was terrified my family would somehow discover, I wasn't actually asking anyone information about my mom and dad because, ridiculously, I didn't want to arouse any suspicion. I did reach out to some people — I tracked down and corresponded with the woman my sister told me was my father's mistress at the time of his death — but talking to my actual family seemed frightening. Then, during a trip to San Diego to visit my mother's sister, I realized that she could fill in some of the gaping holes that remained in my understanding of my parents' lives if I just had the guts to ask questions.

Over a dinner of mediocre Mexican food with my aunt and cousin, I brought up my mother's alcoholism, which was a frequent topic anyway with this bunch, and my cousin readily shared a story that I'd either forgotten or never heard. I knew that my mother's father, who was manic-depressive and did stints in mental hospitals, left my grandmother when my mother and aunt were very young and eventually remarried. He would periodically appear in their lives, but did not act as a father in any real way. My aunt handled this better than my mother, who was deeply hurt by his absence, especially because he still lived near them in Chicago.

One day — and my aunt or cousin didn't know why — my mother decided to take the bus to his house and visit him. She rang the bell, and when he came to the door, he said he couldn't let her in. He was entertaining, and his friends knew nothing about his other family. My cousin recounted how sad my mother got when she shared this story decades later — my cousin was shaking herself when she told it — and also how upset she was when, in her father's obituary, they only referenced the children he'd had with his new wife.

I'd always felt that my mother wore her grief as a badge of pride, that she used it as an excuse. She felt entitled to her pain, and whenever someone else began talking about their problems, she was ready to compete. When we'd shovel her into the emergency room so she could then go to detox, she'd randomly interrupt the nurses questioning with statements like, "My husband died," or "every man in my life left me," a phrase that she must have picked up that one time she went to therapy. She lost a lot of my sympathy because she wanted so much of it from the world, and though I generally acted compassionately toward her, I spent most of my time being angry at her for being such a mess and for making me responsible for it. I couldn't understand why she just didn't want to get better, and I needed to see her trying. You're not supposed to blame addicts "because you wouldn't blame a cancer patient," but it really seemed like she was making a choice, especially at the beginning. I thought she didn't want to get better because then she'd have to take responsibility for her life, and that if she gave up her grief, she'd be giving up her identity.

But as I learned more about my parents and really thought about everything that happened to them, what they went through together and what they went through apart, and when I consider all of the smaller things that happened in their lives that I will never know, my own story started seem impossibly flawed, and so much less important.

In my mother's eulogy, I said, "I feel lucky to be her daughter (most of the time), but I would have loved to be her friend. I wish I could have traveled with her. I wish I could have stayed up late with her, arguing about politics and philosophy. I definitely wish I could have borrowed her clothes, and I can't even tell you how badly I want to have gone to one of her parties."

It sounded like a lovely thing to say at the time, but it turned out to be much more true than I realized. By examining my parents' lives while also examining my own, which I am always doing, all the time, to the point of exhaustion, I've actually started to see my parents not as my parents, but as my friends, and people who I have way more in common with than I could have ever guessed before. I wonder and worry about their relationship and root them on as if I don't know how it all ends. And I find myself commiserating with them. How does anyone get this shit right? If my friends and I are constantly talking about our relationships, our entanglements, our hang-ups and fears, they must have been talking about the same exact things with theirs. Did they freak out or falter? Did they see things happening and wish they could stop them, then watch them happen anyway?

I didn't start My Dead Parents so I could find a way to grieve for my parents, though for a while I thought that maybe I had. But I did end up grieving for them quite a bit, and in different ways. One of the most unexpected results of working on my blog is how much it's led me to think about love. If it's true that my parents were happy, in love, having fun, and accomplishing what they dreamed, I think it's also true that they fell out of love, and that life's complications got the best of them. This is sad. I think that's one reason, despite all the different things that I learned, that I still sometimes resist the shift in perspective, because it gives me something entirely new, and unexpected, to mourn. I hate what happened to them, and I hate that it can happen to anyone. Falling out of love, or waking up in the middle of a life that you didn't want, often feels like the saddest thing I can think of.

I also started to grieve for myself, and realized that in many ways I'd been grieving for years. I'd been grieving the fact that I didn't have the parents I needed, and that I could have really, really used them. Screw being independent, tough, and alone. At some point, I had to admit that I needed a lot more love and support than I'd gotten, and that, if I'd had different parents, or known how to have a different relationship with the ones that I had, I'd probably have made a lot fewer mistakes. It's painful to admit that, while everyone else relies on parents less and less, I occasionally find myself needing them more than I ever have. I recently moved back to Los Angeles, and in the first few weeks, despite being surrounded by friends who would do anything for me, I was overwhelmed by the feeling of being alone for I think the very first time, of having no one I could rely on, or ask for advice. I found myself wishing that there was someone I could call — not necessarily my parents, at least not as I knew them, but perhaps the Platonic ideal of parents, though I know no one actually has those — and be told that everything, all of the small and big shit that was swirling around me, was going to be OK, and that I was going to be OK too.

It was scary to feel so alone and to admit that I needed something I could never have, but it was also liberating, because my need wasn't accompanied by any self-righteous anger about the parents I should have had or thought I deserved, or obscured by guilt or ambivalence. I never wanted this project to be cathartic; I don't think catharsis is a reason to write, and I don't like reading work that's reaching for it. But something must be happening, because when I reread everything that I've written over the past two years, I can't pretend I haven't changed. I have changed a lot.

I think I am finally ready to let these new images of my parents replace the ones I always had, the ones that stood in the way of my grief. I consider a lack of grief to be a lack of love, and I want to love my parents. It's a horrible thing to write, to admit, that I didn't love my parents, but for much of my life, I just don't think I did. My blog is changing that. I don't think children can ever really know their parents, but as I've slowly gotten to know mine at least a little better, I have finally begun to love them, maybe not as my parents, not yet, but simply as people — the people they were, they wanted to be, and even the ones they became.

Whenever I leave you I feel a powerful and wonderfully terrible series of emotions. They begin at the airport as the plane gathers speed, rumbling down the runway. Perhaps it is triggered by the city passing in the distance, but there is an emptiness inside me, a true aching of the heart. It is a longing and a dull sorrow for leaving behind that which I love. I fly off into a vague and fatalistic unknown (at this point I am never conscious of my true destination). It is an unreal eternity. It is as if I were in a spaceship destined for an unknown star, it must be a little like dying. (George to Anita, Feb. 14, 1971)