“Successful.” “Honest.” “Fearless.” “Relatable.” “Strong.”

When asked what characteristics best describe the president-elect, those were the words mentioned most often at Donald Trump’s Des Moines, Iowa, "Thank You Tour". And the perception of these supporters — who showed up to a faux campaign stop four weeks after their candidate had already won — is proof that Trump, whose first month as president-elect has been an assortment of gaffes, bumbles, and broken protocol, is excelling at the thing that matters most: maintaining his image.

In politics, you’d say Trump is effective at “messaging.” But Trump isn’t a traditional politician, and he’s resistant to being analyzed like one: Most attempts to do so have generally misread or underestimated him. To actually understand Trump’s actions — his adult entire life and campaign, but more specifically, since he won the election — you have to analyze as you would a celebrity.

Trump’s tweets, victory rallies, and protocol-breaking meetings aren’t power plays or genius chess moves aimed at sly misdirection. They’re attempts, some more conscious than others, to reinforce his image as the embodiment of the American dream — reaffirming his role as a potent, authentic outsider even as his actual politics threaten to unravel. People think Trump is constantly on the offense, but he’s actually a sly defensemen: a “builder” who knows how to fortify and gild the walls of his castle so effectively that no one can see inside.

Actors become superstars when they come to embody the complex, often contradictory ideologies that guide an age. In the 1950s, Marilyn Monroe’s image made the taboo of sex seem innocent; in the 2010s, Jennifer Lawrence showed that the best kind of independent feminist was the “cool girl” who didn’t cramp a dude’s style.

Trump became a star in the 1980s by acting out the dream of the revitalized American male: reassurance of American capitalist acumen, coupled with the sort of guile and glee that made making money seem, well, fun. That revelry was essential: Before 1940, businessmen like Henry Ford had become their own sort of celebrity, what cultural theorist Leo Lowenthal calls “idols of production,” celebrated for their ingenuity, their hard work, their embodiment of the American spirit. The problem, however, was that most of them were boring: All work and no play made them dull men indeed.

Which is part of why coverage began to shift, over the course of the first half of the 20th century, toward “idols of consumption”: men and women who don’t make things so much as live lives of privilege. When you read about them — in the gossip columns, in magazine profiles — the focus was on where they went for lunch, what they were wearing, the lusciousness of their homes, how they spent their seemingly endless leisure time. (Today we have the same focus, only most of it plays out on Instagram instead of being filtered through the mainstream press.)

Trump was at the center of the Venn diagrams of these two types of idols: a self-styled dealmaker who used the wealth from those deals to consume conspicuously. Yet Trump didn’t drink, smoke, or even have a morning coffee; he loved an expensive steak, but had little concern for fine dining. Trump cares far less about actually enjoying luxury, far more about others knowing he’s enjoying luxury. Which is why he doesn’t live in a private home, but Trump Tower: a place where his lifestyle is written in bold, unmistakable print for anyone who walks in off the street to see.

Flaunting his wealth may have been perceived, in some quarters, as gauche, but Trump figured his flamboyance could become the central engine of his business. The more his image became one of shameless decadence — of Playboy Trump — the more he could use that same image to make deals, sell properties, attract people to his casinos, which in turn allowed him to be more brazen, more decadent, and attract more people, across the globe, to the Trump brand. Decades later, one of his advisers crystallized Trump's appeal to the working-class: “If you have no education, and you work with your hands, you like him. It’s like, ‘Wow, that’s how I would!’ The girls, the cars, the fancy suits. His ostentatiousness is appealing to them.”

Trump’s ‘80s brand rose to prominence alongside celebrations of consumption like Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous and Wall Street, with its ruthless antihero Gordon Gecko proclaiming “greed is good.” The valuation of unmitigated greed of course had everything to do with American masculinity and the nation’s still-fragile understanding of itself amid the Cold War. But Trump was no movie character: He was a real person, and thus proof that this sort of masculine capitalist potency was still alive and thriving.

But in the early ‘90s — with the Cold War over, the Gulf War stalled, and Trump overextended and in bankruptcy — he became a symbol of the past, not the present. And so the self-styled avatar of American success became a punchline. In the late ‘90s, Trump loved to recall the story of looking at a homeless person on the street and realizing that man had more money than he did. For Trump, that moment was one of great sadness: because he’d lost his fortune, but also because he’d lost his relevance. Suddenly, he was a loser.

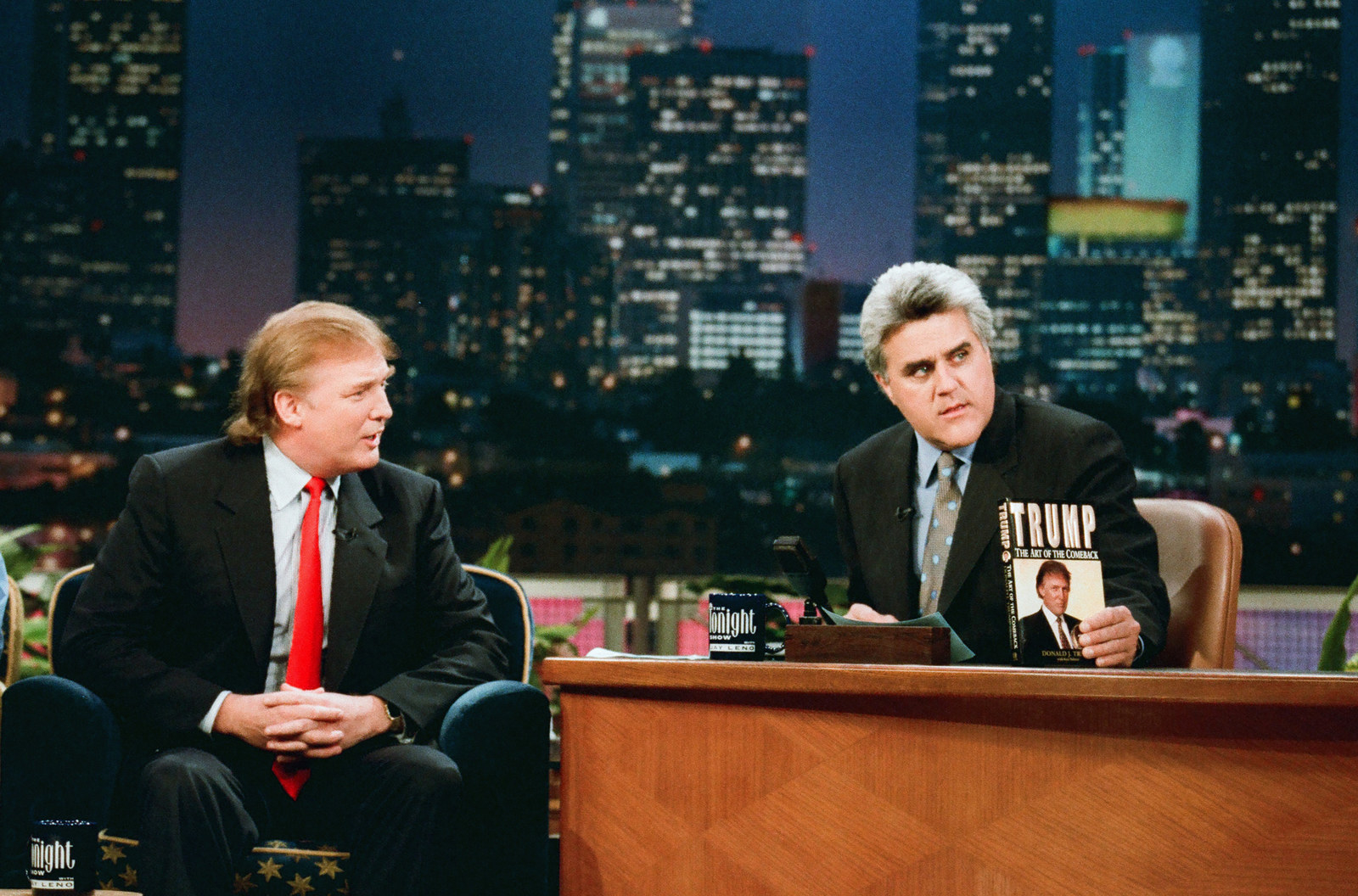

While Trump’s ‘90s melancholy had something to do with not having money to spend, it had far more to do with no one wanting to watch him spend it. The core of his celebrity image — and, by extension, his power — had been compromised, and he spent the bulk of the ‘90s trying to regain it. He endured the humiliation of bankruptcy. He released The Art of the Comeback. He divorced Marla Maples and started dating a rotating carousel of supermodels, which had something to do with his “love of beautiful women,” but was also a reliable way of getting his name in the tabloids and gossip columns.

And Trump still had his casinos — which, even more than his massive New York construction projects, made millions of gambling Americans associate his name with their own ideals of wealth and decadence, no matter how precarious. It didn’t matter if many actually wealthy people thought those casinos (and his newly acquired beauty pageants) were trashy, so long as millions of Americans thought otherwise.

By 1999, Trump’s rebound was in full swing. He teased a run for president on the Reform Party ticket, but pulled out before ever officially announcing his candidacy — because the cost would be too much, but also because he knew, as a third-party candidate, that he couldn’t win.

And Trump, as we now know, is obsessed with who gets to be winners and losers, and he’d only just pulled himself out of loserdom. So he exploited the idea of a presidential run just long enough for it to promote his new book, The America We Deserve — and a series of paid speaking engagements with Tony Robbins — and then pulled the plug.

His businesses may have been healthy again, but Trump, as a celebrity, was still out of fashion. Steve Jobs in his black turtleneck, Bill Gates in his nerdy glasses — those were the men who seemed to embody the American capitalist spirit. Not Trump, who didn’t know how to use the internet and largely ignored the dot-com boom because he thought it would pass.

There was a new type of celebrity, however, that had started to resonate with the American public: the reality star. In Trump, Mark Burnett — the producer behind Survivor — saw the potential for a different sort of reality program. It would be a competition like American Idol, but instead of charisma and natural talent, the driving skill would be business craftiness. Not acumen, or knowledge, but cunning: a particularly American understanding of how capitalism should work, and also an ideal ingredient for reality drama.

Trump was the perfect fit for Burnett’s vision. The Apprentice would be his path back to exposure and, by extension, relevancy: The rhetoric, framing, and shooting style of the show suggested he was the smartest, most skilled, most important businessman in America. Its popularity accomplished the thing for which Trump was most desperate: the broad, global re-visibility of his image, effectively surrounded by dollar signs.

The image-making apparatus around Trump has never been subtle, but The Apprentice took its bluntness to a new level. The theme song consisted of one word: “Money,” reiterated at different lengths and with difference punctuations. The logo featured Trump’s face as a Mount Rushmore monument amid the New York skyline. Most episodes involved some iteration of Trump talking or gesturing toward his wealth (in models, in property holdings) and judging the contestants on their ability to help him inflate it.

No matter that the show’s “boardroom” was a simulacrum, or that the “management jobs” in Trump Inc. intended for the winners were a sham: Reality television succeeds not when it depicts reality, but when it suggests that reality is actually a game with clear winners and losers. Trump wasn’t a contestant in this world, as he had already won all the spoils — a proposition the show never questions, and an image that has now been solidified through 14 seasons.

In truth, Trump was a reality star just waiting for the reality age: No other medium portrays his impulse toward conspicuous consumption and conspicuous demonstrations of power as effectively. With The Apprentice, Trump solidified the reality era–tinged understanding of the American dream: It’s not actual hard work that makes you successful, but the ability to evince the feeling and effect of power and wealth.

The popularity of The Apprentice meant the revival of the Trump celebrity brand: He returned to the cover of People magazine in 2004; he launched Trump University; Trump-branded towers proliferated across the globe. “Trump” meant success once again, and success was an idea that many organizations, especially those in the newly upwardly mobile areas of the Middle East and India, wanted bluntly affixed to their projects.

When Trump began his run for president, his success hinged on his xenophobic policy suggestions and ideological stances. The decision to highlight those positions were made on the advice of strategists who’d figured out a way for him to finally win at politics: If he ignited the smoldering flames of bigotry, these analysts, who’d listened to endless hours of conservative talk radio, surmised, he had an actual shot at the presidency. So what if his image became infused with “racism,” “misogyny,” and “fascism,” so long as the overarching understanding was that of “winner.”

But Trump never would’ve gained the traction that he did, or survived with so little evidence of his actual ability to govern, if it weren’t for his obsessive work on his celebrity image for the last 30 years. Through the flattening narrative of reality television, that image had come to signify powerful, if hollow, concepts of “success,” “strength,” and “power,” not “struggle,” “immorality,” or “intermittent failure, largely dependent on bankruptcy laws.”

In this way, Trump provides the dying American dream with life support: He permits people to ignore the systemic oppression and discrimination that makes that same dream impossible for many, if not most. That dream sustains itself, in no small part, on the likes of Trump: a celebrity whose image, even after all these years, especially after all these years, vouches for its vitality.

For the millions who didn’t roll their eyes at Trump Steaks, who’d frequented his casinos and watched The Apprentice with admiration, a Trump presidency made perfect sense. A vote for Trump wasn’t that different from a decision to purchase one of his books — both are rooted in the idea that a simple decision and small commitment could result in Trump’s aura of success enabling them to find their own.

Trump’s message of prosperity was effective enough to excuse all other parts of him, included his professed bigotry and sexism. For some, his crassness and misogyny was simply an authentication of the part of his image he’d refined on The Apprentice: the propensity to “tell it like it is.”

“Telling it like it is” is a phrase that suggests frankness and honesty, but with Trump and white men like him, it also connotes a willingness to eschew cultural niceties, including the perceived devilry of political correctness. Trump had long been a man of bombast, but what we saw on the campaign trail was something new. Through hundreds of interviews over the last 20 years, he’d evidenced arrogance and a touch of soft sexism, but never the outright bigotry and misogyny evidenced on the campaign trail.

Whether or not Campaign Trump is Trump’s real self matters less than Trump’s own amplification of those traits when he saw that people were responding to them: If they existed before, he tamped them down, wary of how they would affect his brand, especially with the ethnically broad population that went to his casinos, watched his show, and enrolled in Trump University. But people on the campaign trail were responding to the way he talked about Muslims, Hispanics, and immigrants. They loved the way he talked about Hillary — and any other women who criticized him. They adored the idea of building a wall. Trump heard them, and his tentative tests — Should this be who I am? Is this what you love? — became proclamations, extensions of self.

Put differently, Trump owned and incorporated bigotry and soft fascism into his celebrity image because it worked. It made him meaningful in a way that even Playboy Trump and Reality Trump could not be in the 2010s. Through his invocations of the storybook past, he promised an imaginable future: a movie whose ending voters didn’t just know, but loved. No matter that it was implausible, that the narrative twists and turns necessary (forcing Mexico to pay for building a wall on its border with the US, strong-arming China into favorable trade deals, bringing back coal production) were, in today’s world, simply unfeasible.

Which helps explain why Clinton’s invocations of policy — or pointing to Trump’s lack thereof — couldn’t gain traction: It was like trying to point out to a friend that the laws of physics make the plot of Inception impossible. “Stop ruining it for me,” the friend says — they want to believe. But in order to believe Inception, you need an actor at its center convinced of its plausibility, uttering all the implausibilities in a firm enough tone to make everyone believe them.

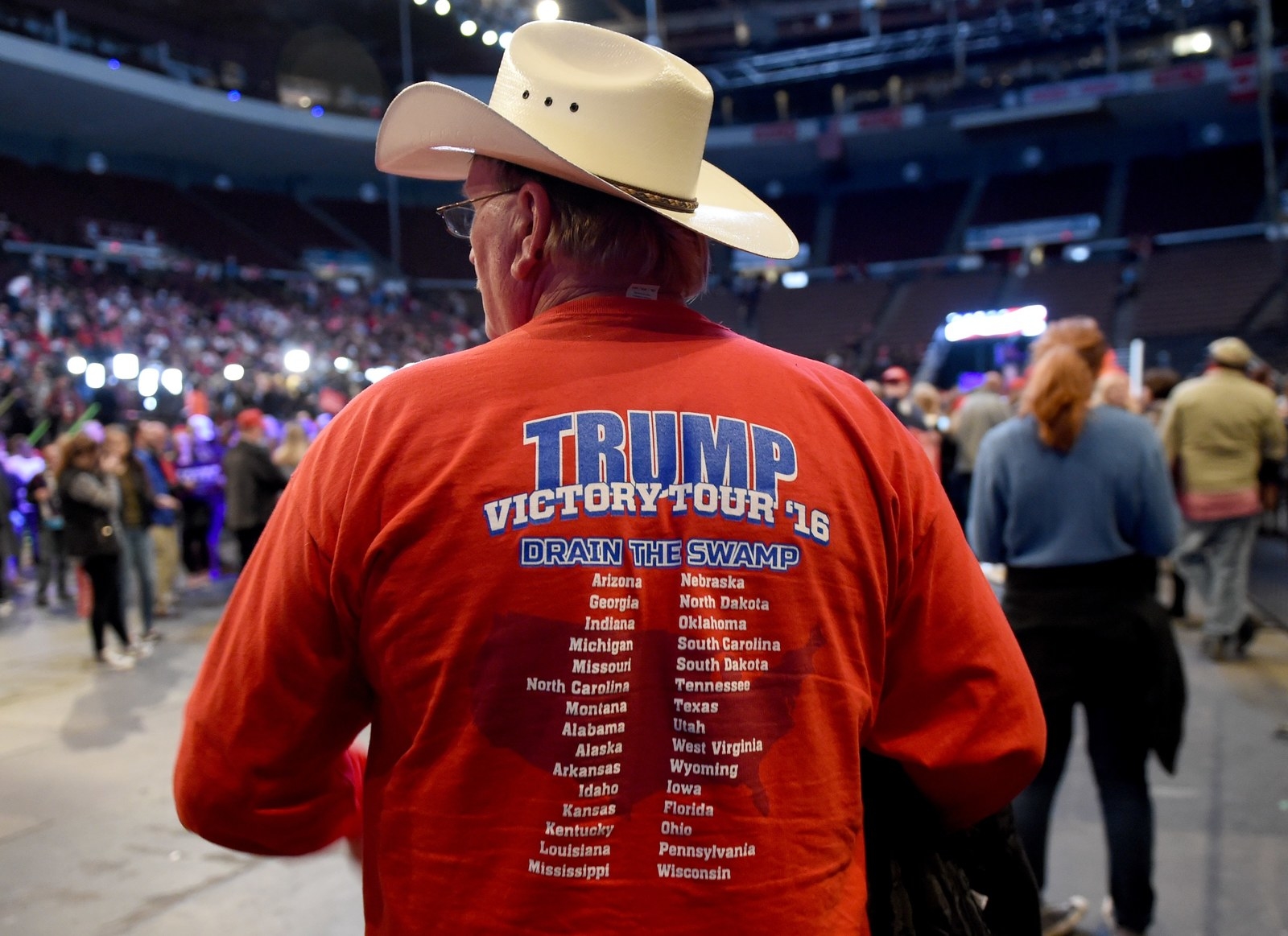

We will build that wall, Trump said, enough times to make it seem true. We will drain the swamp, we will lock her up — messages that, by the end of the campaign, didn’t even need Trump’s invocation in order for them to ring out across the arenas where his supporters assembled. Even Trump’s own averral, issued earlier this week at a Michigan rally, that the idea of locking up Clinton “plays great before the election” but “now we don’t care, right?” doesn’t affect their strength: To deny them would be to question the legitimacy of the entire package of ideas his supporters purchased.

Ideas, not policies. The past, not the future. An imagined world, not the real one. Some of this is, of course, just political craftwork, as effective on the left as it is on the right: Obama, after all, became most effective when “hope and change” became firmly aligned with his own celebrity image. Obama is the most instructive celebrity to study to understand Trump: He might not have had Trump’s two decades of celebrity image making, but he knew how to adhere simple and powerful ideas to his image (Obama had the "Hope" poster, rendered in reds and blues that erased his racial difference; Trump has the "Make America Great Again" baseball cap).

Like Trump, Obama understood the amplifying power of a crowd yelling back those same principles. At an Obama rally, the chants were “yes we can” and “fired up, ready to go” — positive, infective energy during a period when individuals felt stripped of agency and power. The energy at a Trump rally was similarly infective, but negative: The economy had recovered, but not for all; things were better than they were in 2008, but they weren’t as good as their memories of how it had been before.

People joke that Trump needs the rallies to feed his narcissism, but that understates their utility. They boost his meaning when, between rallies, it threatens to disintegrate — as it did most vividly in August, when he insulted a Gold Star family. With their simple, legible messaging, the rallies spackle over the faulty construction of Trump’s embodiment of the American Dream, reinforce it with rhetorical might.

In the weeks since the election, the cognitive dissonance between “Drain the Swamp” and Trump’s cabinet of billionaires has threatened the integrity of his image. Cue: more spackle, this time under the guise of “thanking” the Americans who voted for him. The "Thank You" rallies provide the semblance of a backbone to his otherwise spineless transition, an opportunity to recite the chorus of his campaign even as it’s increasingly clear there’s no verse.

At each stop, he has a prepared teleprompter speech, filled with promises of what he’s going to do (make our military strong again, ban immigrants who “don’t know how to love us”), but when he talks about these things it’s unconvincing. His voice goes into a register that’s un-Trumpian; he sounds bored, and the crowd begins to lose focus. As soon as Trump feels himself losing the crowd, he goes off script — to talk about someone who’s a loser (Evan McMullin, whose name he refuses to use); to remember how great it was vanquishing Hillary; to recite, like the high school quarterback recalling his glory days, a play-by-play of the election results coming in, county-by-county, state-by-state.

But the recitation is more than just bombast and bluster. Like Trump’s obsession with the polls, it reifies the core of his image as a winner. To distract from what he’s done, or decided not to do, with that victory, he simply redirects focus to the process, not the product. His presidency will be, as Molly Ball noted in The Atlantic, that of the perpetual campaign, reminding you of what he represents, not what he does — like a celebrity on an endless press tour, with nothing to promote.

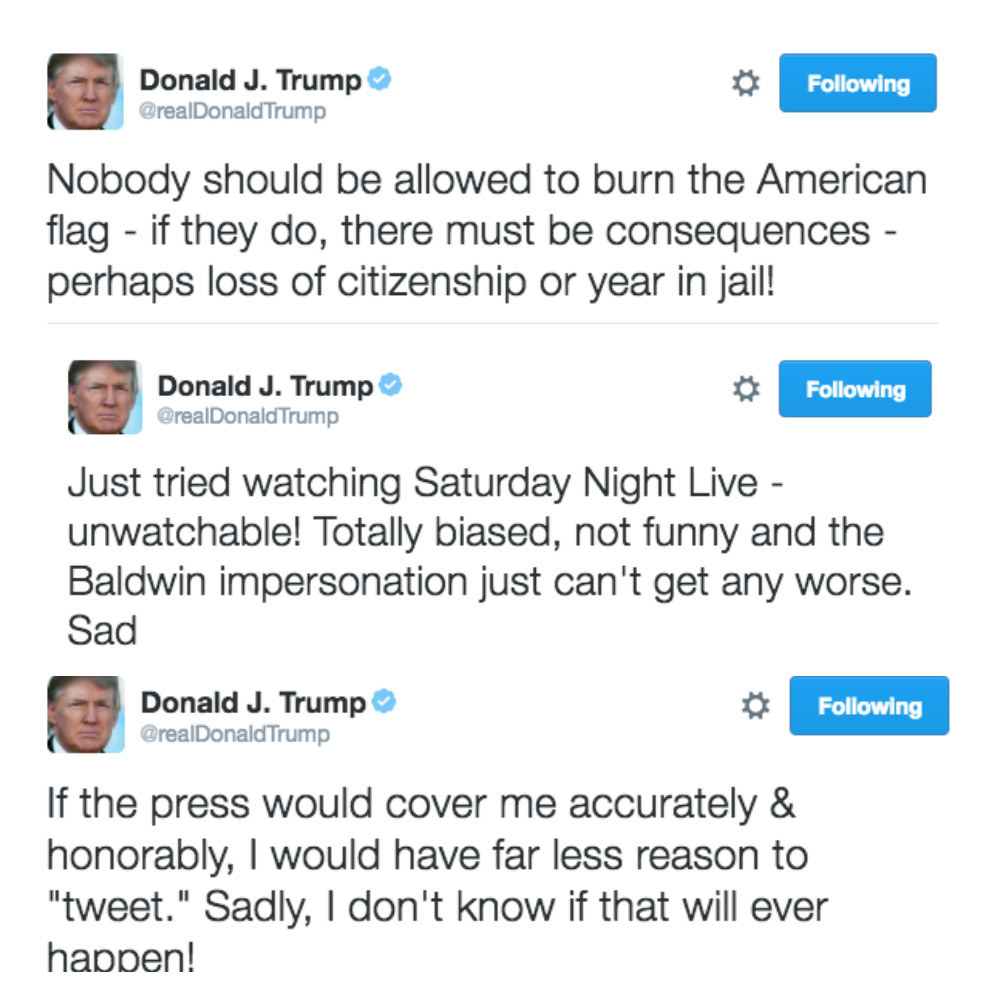

And like a celebrity, part of that promotional tour is tweeting. It’s well-known that Trump is effectively a Luddite. But he’s always been savvy when it comes to the delivery of the message of his image: Playboy Trump proliferated through the tabloids, making him and his power visible to the working-class audiences whose paychecks powered his casinos; Reality Trump used reality television to give a weekly “real” glimpse into his performance of power and wealth, and President-Elect Trump uses Twitter, which, in taking away the filter between the celebrity and his public, creates a persuasive aura of authenticity.

The immediacy of Twitter — coupled with Trump’s distinctive style — amplifies the “tell it like it is” component of his image: People at Trump rallies say they love and look forward to his tweets, but that love is less for what they say (usually decrying something, calling someone a loser) and more for his willingness to say it. On Twitter, Trump doesn’t care who he offends or attacks, he has no fear of the status quo, he has no regard for social niceties. That posture, so effectively communicated through a medium like Twitter, further affirms his “outsider” status — and helps elide the privilege he’s enjoyed since birth.

In the weeks since the election, Twitter has become increasingly essential to the maintenance of Trump’s image and, by extension, his legitimacy as president-elect. He wields it like a flare gun: Don’t look here (the settlement of his Trump University lawsuit, which, upon close scrutiny, reveals that he bilked people like those who voted for him for millions), look here! (Mike Pence getting booed at Hamilton).

And as he’s appointed billionaires to his cabinet, in clear contradiction of his promise to “drain the swamp,” Trump’s used Twitter to stoke the nearly dead flames of a culture skirmish so old it feels like a parody: burning the flag. No matter that the First Amendment, which extends to protecting flag burning, is as central to American identity as the flag itself. Through Twitter, Trump stokes anger that many of his supporters had forgotten existed. Any burgeoning concern over the hollowness of his campaign promises is subsumed by anger — a far easier emotion to channel than regret. Yet again, the idea of Trump supersedes the reality of him.

When Trump first entertained running for president in 1999, he was accompanied on the list of potential candidates by Warren Beatty, Cybill Shepherd, and Arnold Schwarzenegger — and ran at the behest of Jesse “The Body” Ventura, a professional wrestler who had recently been elected governor of Minnesota. Editorials proliferated about the celebritization of politics, but that ship had sailed long before: with John F. Kennedy and the fetishization of his family; with the election of a movie star in 1980; with Bill Clinton’s addictive performance of charisma in 1992 and the scandal, covered with the same tabloid-like tones as the O.J. Simpson trial, that followed.

In 2008, Obama benefited mightily from his celebritization — and suffered when his attempts to do more than just be and symbolize, aka his work to govern, either clashed with or failed to live up to the ideals that had beguiled voters. Yet for all her time in the public eye, Hillary Clinton was not a celebrity: or at the very least, she never managed to accumulate a coherent celebrity image that was anything other than negative. She was shrewish and shrill, unruly and aggressive. She was the status quo, the establishment — the past, but not the “great” sort of past Trump voters desired to return.

When Clinton decided to run for president, her campaign was at a loss to find a single phrase that encapsulated what she meant. The 84 they did come up with are a testament to the diffuseness of her image. It didn’t matter that she had demonstrated real skill at governing, the sort of thing that actually makes change, or listening, the sort of thing that makes people feel that their concerns are met. Her celebrity image lacked coherence; what little there was was easily dismantled by the vaguely evil connotations of a private email server.

Trump’s election illuminates the dark future of American politics: For the time being, résumés, experience, policy, and specifics matter far less than the idea the candidate suggests to the American public, the movie version of his or her life, and how these voters see themselves fitting into the happy ending. Campaign architects have known something like this for years — but as the candidacies of both Clinton and Jeb Bush demonstrate, they didn’t truly listen to it, at least not enough to find a candidate who could couple that sort of celebrity coherence with actual governing and leadership ability.

For journalists, Trump’s election should clarify something more. Many have spent the last month wringing their hands — about the failure to predict his win, but also about the impotence of the journalistic tools that, in years past, would’ve shattered his image and lampooned his campaign. Tax returns, sexual abuse allegations, leaked tapes, wide-scale investigations that illuminate the hollowness of his philanthropy — none of it worked. While it convinced those who’d already rejected his image, for those convinced of his other meanings, it was as effective as calling him a name in the schoolyard.

Showing his hypocrisy and his vileness didn’t shatter the core of Trump’s appeal, in part because Trump’s image as the embodiment and promise of the American dream had already spent 20 years taking root in the minds of those desperate to regain it.

To view Trump as a politician is to believe that the traditional political checks of journalism can erode his image with his base. To view him as a celebrity is to understand that the institutions most critical to his own, fragile idea of his image — Saturday Night Live, the tabloids, the cable news programs, Twitter, paparazzi photos of his hair — are his vulnerability points.

Where would he be if Twitter decided his singling out of individuals constituted harassment and the company suspended his account — thereby taking away his bully pulpit and primary form of image maintenance? What if Saturday Night Live stopped lampooning his ability to lead and started relentlessly interrogating and undercutting his wealth? What if the gossip press doggedly pursued and endlessly re-litigated the torrid details of his life in the ‘80s and ‘90s? What if a celebrity whose image was equally potent and resonant ran against him?

There’s a risk, of course, that all of this could simply fortify him further. We could just be patient and watch Trump’s image go out of fashion again — it happens to all celebrities. But even four years seems like a very long and very dangerous amount of time to wait.

Want more of the best in cultural criticism, literary arts, and personal essays? Sign up for BuzzFeed Reader’s newsletter!

If you can't see the signup box above, just go here to sign up for BuzzFeed Reader's newsletter!