Top of the Lake’s Robin Griffin — played by Elisabeth Moss — is a rarified sort of female protagonist. As a detective specializing in crimes that involve sexual abuse (and a sexual abuse survivor herself), she’s a less cartoonish version of Law & Order: SVU's Olivia Benson. She’s tough and capable, beat-up and broken. She’s made of china and steel. She’s difficult to love but impossible to ignore.

In Season 2 of the series (which Sundance is rolling out over the course of three days, starting Sept. 10, after which it will be available on Hulu), the tenuous balance between Griffin’s outer strength and inner fragility begins to fall apart. And as she attempts to solve the murder of a sex worker — pregnant with a baby who does not share her DNA, stuffed in suitcase and pushed out to sea — the trajectory of the series starts to fray as well. There are too many broken narrative threads: too much coincidence, and little coherence. This season, like the one before, is about misogyny, but it’s also about the way women are reduced to their status as mothers. It explores both what it means to be a mother and the way women, desperate for motherhood, may turn their backs on other women. It’s also about surrogacy and rape culture, race and sex work, and whether good men exist.

It’s arguably trying to do too much — many of the tensions, especially those regarding the racial dynamics of sex work and surrogacy, get frustratingly lost in the tangle. Yet Top of the Lake is the first piece of fictional media I’ve seen in months that has made me feel anything. We’ve all figured out the places to find pat, soothing answers: That’s why, when the news is at its most exhausting, I turn to reruns of SVU. But when I want to see my own fatigue and conflict with the misogynist world reflected onscreen, there’s Top of the Lake. It’s a different sort of self-care; instead of muting my confusion and frustration, it acknowledges and amplifies it.

It’s no coincidence that this narrative was cocreated, written, and directed by Jane Campion — one of the few female directors who’s managed to navigate the enduringly sexist and exclusionary terrain of Hollywood. In work ranging from The Piano to In the Cut, she’s explored what happens when women trespass into worlds (physical, emotional, occupational) and access knowledge that has been hidden from them — and the violence that often follows when they do. She’s enthralled by the misogyny of these worlds, obsessed with depicting them in a way that suggests both her disgust and their endurance.

The second season of Top of the Lake explores this theme in far more ragged fashion than the first, in which Griffin investigated the disappearance of a pregnant Thai teenager in a small New Zealand town. That season, like so many projects by filmmakers who’ve recently come to television, felt like a taut and deeply atmospheric piece of storytelling. The six episodes were supposed to stand on their own: one season, and then done. But when they were both in Los Angeles for the Emmys, Campion slid a napkin under Moss’s hotel room door with a simple question: TOTL 2? Moss agreed, and Campion recruited Australian native Nicole Kidman — who’d previously worked with Campion in the 1996 adaptation of Henry James’ The Portrait of a Lady — to costar, along with Gwendoline Christie, best known for her role as Brienne of Tarth in Game of Thrones.

But Christie, who eventually becomes Griffin’s partner, is no Stabler to Moss’s Benson, because Top of the Lake Season Two is not a buddy cop procedural. Like Season One, its primary register is noir, with an accompanying dedication to unearthing the darkest inclinations of “proper” society — in this case, the clean, sunny streets of Sydney. While SVU suggests that New York is filled with individual sexual deviants, Top of the Lake argues that society’s natural inclination isn’t deviance, per se, so much as a fundamental hatred, mistreatment, and devaluation of women. Where SVU offers closure at the end of each 42-minute episode, Top of the Lake is diffuse and meandering. Instead of localizing blame on an individual, it diffuses it broadly: There’s more than enough for everyone.

In Season 1, that blame was spread across Griffin’s fictional hometown of Laketop in New Zealand. The police, her friends, and her family were all complicit, in some way, in maintaining a world that allowed the sexual exploitation of young girls to go unpunished and unremarked upon for decades. Still, the season ended with something like closure. Griffin, who’d survived a gang rape as a teen, seemed to be approaching some approximation of peace, perhaps even happiness. She solved the case, figured out the identity of her rapists, and found a good guy who made her feel safe and loved.

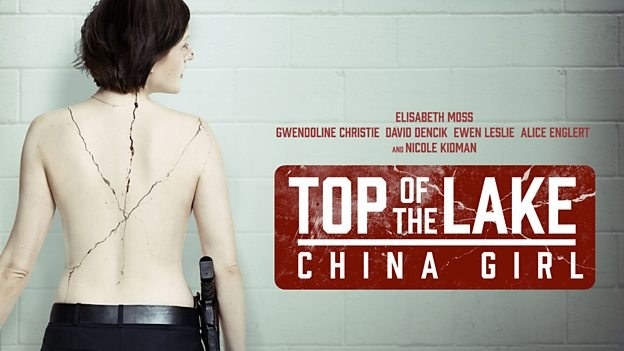

But in the beginning of Season 2, the most delicate parts of Griffin have fractured once again. (The promotional artwork goes so far as to depict Griffin as a china doll, literally broken into pieces.) On the day of her wedding to the guy from Season One, he’s arrested — and found in the company of another woman. On the beach where the wedding was to take place, Griffin watches as her wedding dress is hoisted high above a bonfire before bursting into flames: an effigy for love. In that moment she announces that she has to go back to work. Like so many women, she reacts to pain by turning inward, to the only person she can trust, and focusing on the thing she knows she’s good at.

Griffin returns from New Zealand to Australia, where she’d worked with local law enforcement in the past. But back in Sydney, she doesn’t have any place to live, nor does she have any money, or furniture, or roots. She’s still dealing with the same institutional bullshit she did in New Zealand, with coworkers who either want to fuck or ridicule her. Her supervisor hits on her repeatedly and becomes aggressive when she denies him. He also keeps insisting that she meet with the cop who roofied her back in New Zealand for a “reconciliatory” process. And her one potential female ally in the office is secretly tasked with keeping an eye on her.

There’s a sense that Griffin, having spent her adult life dealing with this sort of thing, isn’t just fatigued, but fraying. In New Zealand, she dressed in comfortable clothes and puffy vests; her demeanor was cool, collected, even wry — the female version of the hard-boiled noir detective — even as her investigation touched on deeper and deeper forms of darkness. When she lost her shit, she inevitably regained it. In Australia, she drinks more, usually while sitting on the floor of her empty apartment. She wears a rumpled uniform of slacks and blazers. She’s often sweaty and disheveled; she spends the bulk of an episode drunk. It’s not clear that she’s even a particularly skilled detective. Everything in her life seems to be telling her she has no place here.

Yet part of what brought Griffin back to Australia was her daughter, Mary (Alice Englert), whom Griffin gave up for adoption after being raped as a teenager. Mary, now a teen herself, lives with her adopted parents Pyke (Ewen Leslie) and Julia (Nicole Kidman) in a posh, idyllic suburban home. She’s also rebelling against the bourgeois world in which she was raised, replacing her parents’ love with that of a greasy pseudo-Marxist who lives above a brothel and psychologically and physically abuses her. She’s deeply involved in his world — its affectations, its intellectual posturings, its self-righteousness – when Griffin responds to the letter Mary sent years ago, asking to meet.

At the same time, Griffin’s attempting to solve the mystery of the woman stuffed in the suitcase, pregnant with a baby that’s not hers. What unravels from there involves a network of illegal surrogates (unlike the United States, commercial surrogacy is against the law in much of Australia), a faked pregnancy, a bunch of fucked-up guys who go to the brothel, and a lot more twisty plot, only some of which ultimately makes sense.

The plotlines involving Griffin, her daughter, her brother, her police partner, and the brothel that serves to connect them all interweave in improbable ways. Yet I found myself forgiving those improbabilities in favor of the larger themes they yield: the persistent labels of virgin and whore and mother; the fantasies mapped onto each and the messiness that occurs when those archetypes are muddled; the surveillance of women’s bodies and sense of ownership that extends from it; and the blinding desperation that fills women who can’t become mothers in a world that doesn’t know how to process those who aren’t.

If that all sounds exhausting, try being a woman living through it. Top of the Lake is set in Australia, written and directed by New Zealanders and Australians — but those who excuse or endorse misogyny are not new revelations in the global landscape. Misogyny and rape culture are the air we breathe, the water we’ve swum in for so long we’ve forgotten its frigidity. What Top of the Lake did in Season 1 — and what it continues to do, however unevenly, in Season 2 — is poke and prod us where we’ve become numb.

But as much as the series, and Campion’s work in general, is pervaded by misogyny, that is not its defining quality. Top of the Lake is not, ultimately, the story of men who hate, mistreat, or otherwise devalue women. It’s about women’s imperfect, volatile, overwhelming strength — and how it allows them to become survivors of a world that rejects them, instead of the victims of it. ●