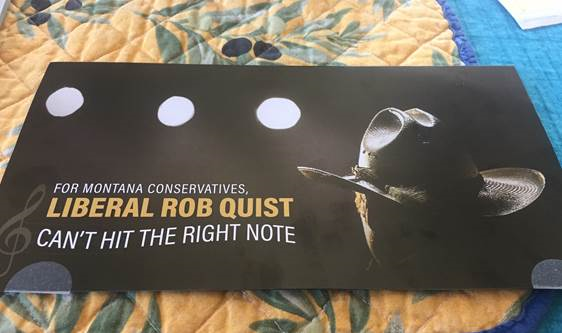

On April 26, the Washington Free Beacon — a publication out of Washington, DC — broke what, to its mind, was a major scandal in the special election for the Montana House seat vacated by Republican Ryan Zinke. “Montana Democrat Rob Quist Is Regular Performer at a Nudist Resort,” the headline declared. The Republican National Committee, which is backing Quist’s opponent, Greg Gianforte, quickly sent out an email blast, declaring “The more Rob Quist’s past is laid bare, the more his claim to represent Montana values is exposed as another charade.”

The story was next picked up by USA Today, which added additional context: “According to his campaign, he doesn’t discriminate about which gigs he takes,” the piece explained. “And no, Quist is not a nudist himself, nor does he perform in the nude.”

The resort where Quist performed is indeed a nudist resort. But to suggest that Montanans would be scandalized by this choice of venue is to fundamentally misunderstand Montana, where the standard dress code at dozens of natural hot springs in the state is “clothing optional.” The first time I saw a naked adult was at a hot springs in Western Montana; many Montanans will tell you something similar. If anything, voters who received that email blast from the GOP were more offended by an outside attempt to define “Montana values” than someone playing music, fully clothed, at a resort.

The story — and the GOP’s aim to exploit it — points to the problem with attempts, both financial and ideological, to transform the races in Georgia, Kansas, and now Montana into political bellwethers. In trying to nationalize these races — and framing them as macro-commentary on politics in America — we lose sight of the actual lessons they can teach us.

Some of those lessons are simple: to remember, for example, that endorsements are unpredictable variables. But others are more complicated, and frustrate the inclination of both Democrats and Republicans to turn every race into a national statement. The Montana special election won’t be a referendum on Trump. It won’t even necessarily tell us what will happen in the midterms. But it, and Montana politics in general, does offer a master class on something even more important: namely, how to cultivate and actually sway one of the most valuable, and increasingly rare, of political entities — the independent voter.

Here’s what you need to understand about Montana before all else: It’s a state where 56% of voters backed Trump — but that same election, 50.2% also voted for their Democratic governor, Steve Bullock. In 2012, 48.6% voted for Senator Jon Tester, also a Democrat. Traveling over a thousand miles in the state, I talked to many Montanans who’d voted this way — and were incredibly proud of it. In Montana, the independent voter isn’t a mythical unicorn. It’s a way of life.

Daniel Zolnikov, a fresh-faced member of the Montana House who recently won his third term as a “liberty-minded” Republican, put it this way: “People who aren’t from here think there’s Republican and Democrat, and maybe some Libertarian here. But Montana is filled with independents. People actively try to find a reason to vote across the ticket.” A sixtysomething at a Rob Quist fundraising event echoed the sentiment: “I’ve never voted straight in my whole life.”

Outsiders look at Trump’s double-digit win in the state and quickly dismiss a Democrat’s chance at winning the House seat. But Montanans vote differently: They vote for candidates more than parties, and they vote for people who they feel will do right by Montana and its citizens. That definition of “do right” changes from place to place, but there’s a reason that conversations about religion and abortion are largely absent from this race and many others in Montana, while questions of public lands access, resource management, and the creation of a Montana sales tax come to the fore.

Of course, there are liberal and conservative strongholds across the state — people refer to the college town of Missoula as “The Kremlin,” for example, and former mining towns like Butte and Anaconda have a strong union legacy. But as a retiree dressed in a cowboy hat and a suede vest told me, the uniting forces aren’t partisan so much as populist. “Historically, there’s been a long and solid connection between the people on the farm and the people in labor,” he said, “and a second connection between them and the candidates who pledge themselves to their cause.”

Like other places in the United States, that coalition of working-class interests — and candidates authentically dedicated to them — has largely dispersed. But that enduring populist inclination helps explain Trump’s success, as well as that of Bernie Sanders, who won the Democratic primary with 56%. It's also why beloved ex-governor Brian Schweitzer got away with proposing statewide single-payer health care: The inclination to universally help the working men and women of Montana trumped the sort of political antipathies that prevent its success nationwide. It’s why Quist came out hard against the latest House health care reform bill. It’s also why a recent endorsement of the bill by Quist’s opponent, Greg Gianforte — given on a private call to lobbyists that was then leaked to the press — has been treated as a small scandal. (Gianforte has since stated that he would not have supported the bill, as it had not yet received a CBO score: “I need to know that in fact it'll bring premiums down, preserve rural access, and protect people with pre-existing conditions,” he told Montana Public Radio.)

Montanans don’t like big government, but they also have very little tolerance for getting screwed over. One way to prevent that is by preventing any one political party from obtaining too much power. “Montanans tend to be more independent,” Andy Shirtliff, who works with the Governor’s Office of Economic Development, told me. “They hopscotch on the political map. Voting for both Dems and Republicans means checks and balances, and that’s what you get with the way we vote.”

Montana’s political makeup used to be shared by many other states in the Mountain West: the state legislature was usually red, but the governor's office was blue, with periodic switches. Idaho, now one of the reddest states in the United States, had a Democratic governor (Cecil Andrus) from 1971 to 1977 and 1987 to 1995; Wyoming has switched back and forth between a Democrat and Republican as governor for the last 50 years. Utah periodically elected Democrats before consolidating around Republican rule; Colorado did the opposite. With one party ruling the state legislature and another in the governor’s office, compromise was the watchword, instead of the dirty word it’s become today. Without compromise, nothing gets done, and Montanans in particular had (and still have) very little tolerance for inactivity.

Many of the conservative-leaning voters I met talked about the state legislature’s tea party candidates — who, like their federal counterparts, have largely become obstructionists to the passage of any sort of bill — with disdain. Just the week before, the inability to compromise sank a vital infrastructure bill, one that would’ve benefited both ranchers and city-dwellers, veterans and schoolchildren.

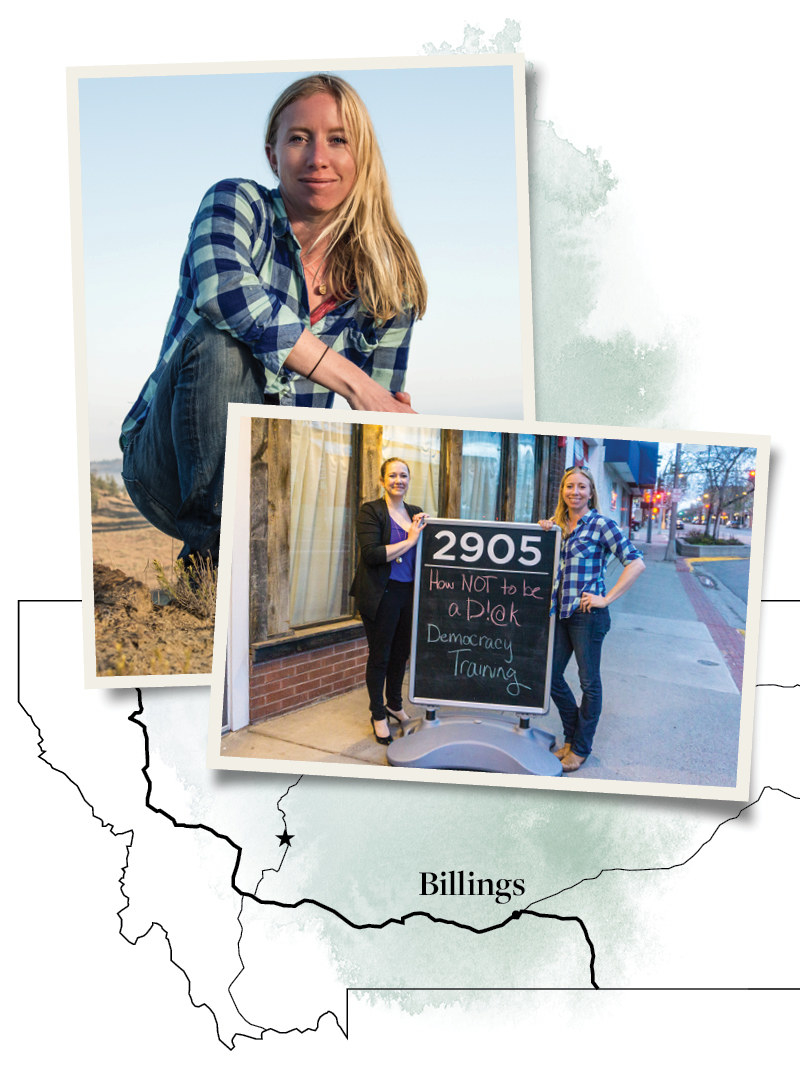

Across the political spectrum, people fear that “the Montana way of compromise” is coming to an end. Blame the tea party; blame radicalized liberals; blame Trump and political polarization. “I hate that the national way of politics is influencing us,” Alexis Bonogofsky, an organizer and activist who ranches outside of Billings, told me, “instead of us influencing them.”

Enter: the 2017 special election for Montana’s sole seat in the House of Representatives. Ryan Zinke won the seat in 2015, succeeding Steve Daines, a Republican who’d vacated in order to run for, and eventually win, Democrat Max Baucus’s Senate seat. When Trump selected Zinke to serve as secretary of the interior, many Montanans, including those who had voted for Trump, heralded it as one of his only solid cabinet picks. “Working together as state senators, I found Ryan to be a quick study, and a thoughtful decisionmaker,” says Taylor Brown, rancher and owner of the Northern Ag Network, which broadcasts on 60 radio and television stations across the area. “When it comes to public lands and grazing, he'll seek input form those of us with first-hand experience.”

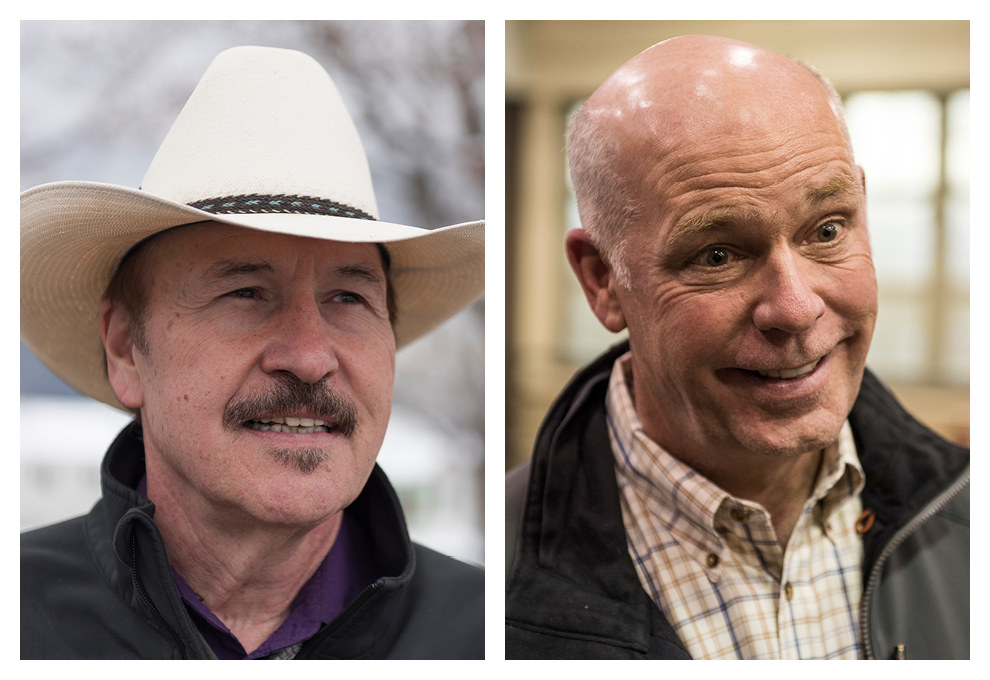

To compete for Zinke’s vacated spot, the Republicans chose Greg Gianforte — a Bozeman businessman who sold his company to Oracle for $1.5 billion. Gianforte was fresh off a 2016 loss to Steve Bullock in the governor’s race, where he had failed to effectively counter his opponent’s messaging that he wasn’t a real Montanan. Gianforte grew up in San Diego, went to New Jersey for college, and eventually came to Bozeman to start his business and raise his children. His past, coupled with rumors that he was considering a run for the New Jersey governorship, was enough to paint him as a carpetbagger.

Before the election, Gianforte had contributed to the campaigns of many Republican House and Senate candidates, including the white nationalist candidate out of Columbia Falls, Taylor Rose. His goal, according to Helena political blogger Don Pogreba, was legislative deadlock — and subsequent failure on Bullock’s part to actually get anything done during his tenure. That goal was (at least in part) achieved; still, voters overwhelmingly favored a hamstrung Bullock over Gianforte.

“These millionaires from Bozeman, they’re the new oligarchs.”

Gianforte also struggled to counter the narrative that he was just another rich billionaire from Bozeman — a place rapidly filling with outsiders. Across Montana, the city is now known, as “Boze-Angeles.” “People in Montana have a long memory for what the copper barons did to the working man,” one Helena resident told me. “These millionaires from Bozeman, they’re the new oligarchs.”

Even amongst those who support Gianforte, the general consensus is that he lacks charm. “Greg’s kind of like an IT guy who’s been moved to sales,” Zolnikov told me. “There’s a reason he’s doing commercials and not public appearances,” a political adviser from Helena said.

In the governor’s race, Gianforte tried to counter the connotation of the Bozeman billionaire by posing for campaign photos with a five o’clock shadow and playing up his hunting acumen. He tapped a Eastern Montana rancher, Lesley Robinson, to serve as his running mate. At the same time, much like Donald Trump, Gianforte tried to position himself as a job creator — even though his company’s primary product was software that outsources “back offices” to locations outside of the United States. (As Josh Manning, a civil rights investigator in Helena, put it, “He made his money on software that un-employs people.”)

Gianforte’s entry into politics is largely believed to be the work of Senator Steve Daines, his former colleague. Like Daines, Gianforte is a religious conservative; unlike Daines, Gianforte has largely kept those views to himself. When, on a recent episode of Voices of Montana, broadcast on the Northern Ag Network, a caller asked him about a significant donation to a creationist dinosaur museum in eastern Montana, Gianforte deflected, listing all the other organizations he donates to, rather than defending or even repeating the word “creationist.”

“Daines is the most dangerous politician in the West,” Alexis Bonogofsky told me. “He’s the puppet master. He’s why Gianforte's running; he’s why Zinke’s in the cabinet. There’s not a Dem who could beat him — save Brian Schweitzer.” And Daines would love to have Gianforte — his old coworker and ideological ally — working with him in the House.

In his office in the basement of a library in Malta, an extension agent named Marko laid out a massive map of Montana on his desk. He traced his finger along the freeway starting up in Kalispell (in Northwest Montana), down through Missoula (home to the University of Montana), past Butte (union stronghold), Bozeman (home to Montana State University and many billionaires), and Billings, effectively dividing Montana in two.

“That part there,” he said, gesturing to the section to the south of the line, “that’s the boot. And what the boot does is kick the rest of us up here in the ass.”

Like so many Western states, that divide is rooted, at least in part, by rural concerns versus urban. But not entirely: Great Falls, the third-biggest city in the state, falls outside of the boot. So does the capital of Helena. The divide is more about money versus less money, about ag versus tourism, about the places where outsiders have moved in and the places where they haven’t, about conservation versus land access. People from the boot are hippie environmentalists who’ve never had to make money from the land — or so the stereotype goes — while people outside of the boot are backward hicks.

Every Montanan congressional candidate has to play well with both the boot and the non-boot, appealing to those who feel anxious about getting their asses kicked and those who don’t feel like they’re doing any ass-kicking.

“In Montana, there’s a real premium on knowing people.” So says Deirdre McNamer, a novelist from Missoula who grew up with Quist. “It produces a different way of judging candidates: Do they know what life is like?” The general feeling, across the state, is that growing up and living outside the boot endows you with that sense; if you grow up elsewhere or live in the boot, it’s almost impossible to achieve.

Still, you can try to counter the connotations of coming from the boot: Gianforte has played down the size of his house outside of Bozeman, where some of his fellow billionaires live in sprawling ranches they access by helicopter straight from the airport. But Gianforte, according to his supporters, isn’t your typical Bozeman billionaire: “He definitely doesn’t live in a mansion,” Taylor Brown told me. “He's an avid outdoorsman and hunter. Just go look in his freezer and see how many species of game he has in there.”

Quist now makes his home in Kalispell, but he grew up in Cut Bank, a city of 3,000 on the edge of Glacier Park, the Canadian border, and the Blackfeet Reservation: prime non-boot country. He’s also fifth-generation Montanan, a point he plays up in commercials, where he shoots his great-great-grandfather’s musket.

What’s more, he’s been a touring musician and songwriter his entire adult life: McNamer remembers watching her brother and Quist teaching each other songs at the local drive-in movie theater. As a member of Mission Mountain Wood Band and Montana Band, Quist toured internationally, nationally, and all over the state. Most Montanans have seen him perform in some capacity, on some stage, at some point in their lives. As one supporter told me, “there isn’t a county fair he hasn’t played.”

“Just go look in his freezer and see how many species of game he has in there.”

Like Gianforte, Quist has no previous political experience. But he beat out presumed favorite Amanda Curtis, a progressive Democrat from Butte, for the nomination. The general consensus was that Curtis wouldn’t have won, at least in part because she’s a woman, and a combative woman at that. Montanans like to tout the fact that they sent the first woman to the elected national office all the way back in 1916, but a quiet sexism still pervades state politics: The state hasn’t elected a woman to national office since. Curtis also lost the nomination because Quist went out to counties in eastern Montana where the Democratic Party had gone dormant, restarted the organizations, and earned their votes — a strategy that’s widely considered to have been hatched by former governor Schweitzer, who still functions as a sort of Montana political don.

Schweitzer understands what it takes to get Montanans to vote across party lines: the appeal to “real Montanan values,” no matter how imaginary a concept that might now be. Put differently, even if the idea of a “real Montana” is increasingly difficult to live or pin down, Montanans still wants legislators who still seem to embody it. This “real Montana” leader promises to remain independent, to protect the 2nd Amendment, to protect public lands, to resist DC forces, and to do right by Montana, whatever it takes.

Quist is spectacularly easy to frame this way. Whereas Gianforte has a section of his website devoted to pictures of “Montana Moments” — essentially documenting that he and his family spend time outside — Quist’s site is filled with shots of him smiling balefully in his cowboy hat. Gianforte’s a billionaire, with investments and interests all over the world; by contrast, Quist comes off as a humble troubadour, whose actual job is listening to and telling the stories of people who live here. Quist even explicitly addresses the “real Montanans” who generally get overlooked: he’s pledged to support a better quality of life for Native Americans; he explicitly supports women’s reproductive rights and will fight the defunding of Planned Parenthood.

Quist’s campaign knows that the vast majority of people in Montana either have heard Quist play, have met him in person, or know someone who knows him personally. Even though most of his fundraising has come from out of state — spurred by efforts, like those of Daily Kos and Swing Left, to influence the election — he has the sort of grassroots support and name recognition that’s impossible to buy. At a breakfast cafe off Highway 1, a server had a Quist sticker on her ordering pad.

“Rob’s been singing about being nice to people and doing right by them for years,” she said. “There’s not a bone of ill will in his body.” The server, who was around 50 and was so pleased someone had asked about her sticker, recently helped throw a fundraiser for Quist at the local Elks Club. “I pray for Rob every night,” she told me.

I heard variations of this kind of familiarity with Quist all across Montana: in the tiny town of Virgelle, in Fort Benton, in Billings, in Missoula, in Bozeman. A thirtysomething named Lynnette, who I met in a bar in Great Falls, told me that “Rob speaks to all of us, not just certain Montanans.” Her friend, who couldn’t be named because her work is associated with the government, chimed in: “What does Gianforte know about anyone in this bar?”

The prevalence of Rob Quist signs, and the embrace of his message, can be linked to Quist’s political touring schedule: He’s been crisscrossing the state for weeks, visiting every Native American reservation, showing up at phone-banking events, knocking on doors in college dorms, facilitating women-to-women phone banks, hosting small public fundraisers, shaking hands and posing for pictures in his cowboy hat. His schedule is on his website; his social media, led by his campaign’s young staff, is incredibly active. By contrast, Gianforte has been mostly invisible, appearing in public with Donald Trump Jr., Mike Pence, and at a smattering of private fundraising events. His communications director ignored repeated attempts for an interview or for information on future appearances; he's only recently embarked on tours of smaller towns across Montana. It’s far easier to suggest Gianforte’s an out-of-touch non-Montanan billionaire when he’s hardly in sight.

Yet Quist’s perfect Montanan narrative has also come into question. A review of hunting license applications turned up that Quist hasn’t applied for one in 15 years — a point the Gianforte campaign is playing up as proof of his “fake” Montana values. But the biggest issue has been Quist’s financial past, which includes a number of tax liens and the failure to pay a subcontractor for work on his roof. The Quist camp has responded by arguing that like many other Montanans, Quist has struggled; what’s more, many of his financial issues are related to a life-saving gallbladder surgery in the 1990s that nearly bankrupted him (and that, today, he uses to argue for universal health care).

For some voters, that argument works: “Who hasn’t had a tax lien against them?” one Quist supporter asked me. But for others, the message that Quist just doesn’t do right by people has stuck. At a taxidermy shop in downtown Anaconda, the owner put it this way: “Look, I can’t have someone come in here, have me do work, and then not pay me. Quist stiffed that subcontractor. That’s not right.” Or, as a medical sales rep from Townsend told me, “My family’s had financial struggles. They nearly lost the ranch. But they never did something like that.”

On an unseasonably warm Friday night in North Central Montana, Quist was set to play a song or two with his daughter, also a musician, at the Great Falls Do Bar. Like many bars in Montana, the Do is a hybrid drinking/eating/casino joint; in the area reserved for music performance, 150 Quist supporters were crammed into a dark room. The median age in the room was about 65, and included Arlyne Reichert, a 90-year-old who helped rewrite the Montana constitution in 1972, a fiftysomething woman wearing a pink “I Stand With Planned Parenthood” shirt, and Gerry Jennings, who’s become the face of the resistance in Great Falls.

“Every month, we get a group of about 100 together and learn how to door-knock and write effective letters to the editor,” Jennings told me. “I’m 76 years old and I don’t care who I piss off. I’m just working as hard as I can.” Jennings grew up Republican in Rochester, New York, and moved with her husband, now a retired hand surgeon, to Great Falls in the 1980s. Today, her job is a mix of gathering together like-minded people and also working on her more conservative social circle. “Last week I wore this ‘Rob Quist: Montana Not For Sale’ pin to church,” Jennings said. “And I had more people come up to me and talk about it. Everyone should wear it to church!”

At the Do Bar, Quist played a song and worked the crowd in his cowboy hat, pressed cowboy shirt, Wranglers, and boots. He’d be wearing a similar outfit the next day at a microbrewery in downtown Helena, with the crowd notably younger and performance geared up — although, like at any gathering in Montana, there’d still be a handful of cowboy hats, coveralls, and elderly men in bolo ties. The lesson you learn in Montana, over and over again, is simple: just because a person looks a certain way does not mean that they will vote a certain way.

In an editorial for the New York Times the day before, Governor Steve Bullock commented directly on this sort of scenario. “On the night that Hillary Clinton got 36 percent of the vote in Montana, I won re-election comfortably, running on progressive ideas and against an extremely wealthy Republican opponent,” Bullock wrote. “Ever since, national reporters have asked me whether Montana Democrats have some secret recipe, given that we’ve won the last four elections for governor, that might be used in national campaigns. I tell them yes, we do.”

That secret, as Bullock elaborates, is simple: “Spend time in places where people disagree with you,” he said. “People will appreciate it, even if they are not inclined to vote for you. As a Democrat in a red state, I often spend days among crowds where there are almost no Democratic voters in sight. I listen to them, work with them, and try to persuade them.”

The idea that you should actually engage in dialogue with people who might not automatically support you, and give them reasons to do so — especially after this election — feels revelatory. But as Bullock points out, in Montana, it’s necessary. Alexis Bonogofsky adopted a similar strategy when she successfully organized ranchers and environmentalists to prevent a new mining operation on Otter Creek, east of Billings. Anne Miller, who lives in Jordan, Montana — a place so flat “you can watch your dog run away for three days” — sees “insane” opportunities for collaboration between the preservationists and the ranchers who’ve been there for generations. “The perception of a 'win' has become more important than the issues themselves," she said. "There are so many mutual goals — it annoys the hell out of me when people don’t see it."

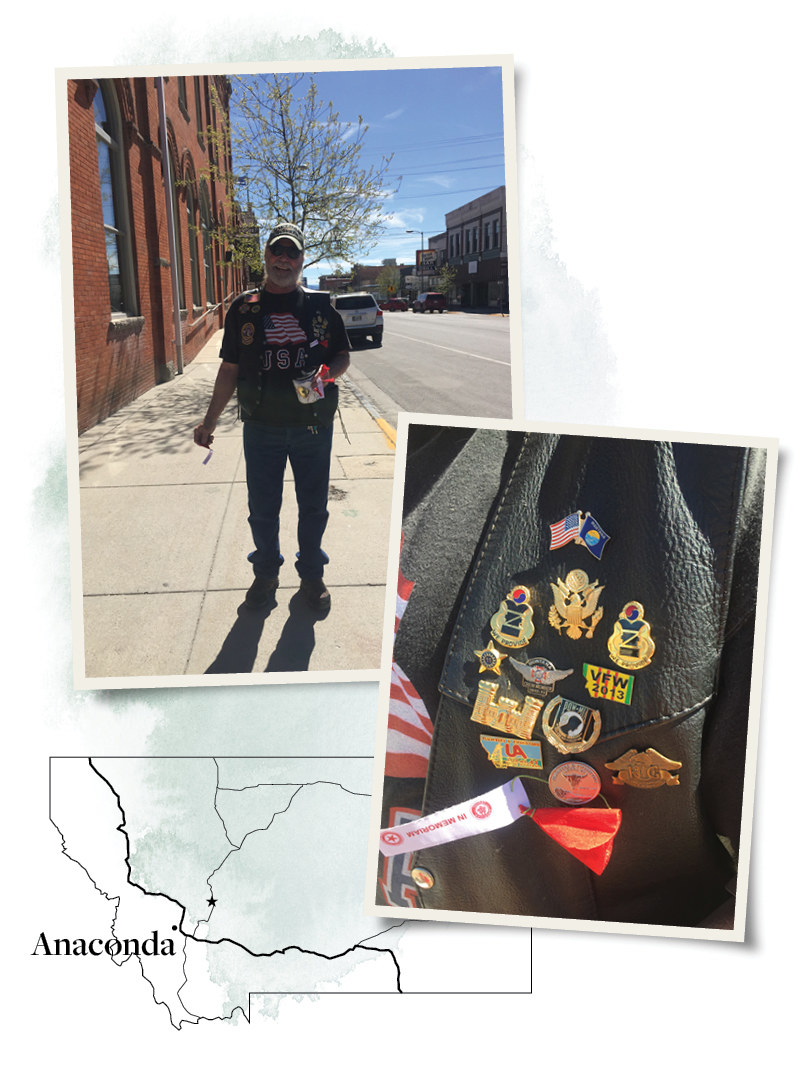

On the hills that surround Anaconda, the smoke stack of an old copper minds looms like an old memory. At first glance, the town looks like a small, burned-out mining town, but it's on the slow but steady road to recovery. It's also a Democratic stronghold: It hasn’t voted for a Republican presidential candidate since Calvin Coolidge.

Across from a new cafe that looks like it could be in Brooklyn, a burly guy named Mike Blume was standing on the street, wearing an American flag shirt and a leather biker vest. He asked if I’d like a poppy — the traditional symbol for a veteran’s aide — and told me he was raising money for disabled vets. He’d grown up in the area, the son of a used car salesman, and when he graduated from high school he started fitting pipe at the Anaconda Copper Mine. He got drafted and went to war, but the mine saved his spot at work; when the mine closed, he started fitting pipe all over the West. When I asked Mike his feelings on the special election, he give me a big belly laugh. “I’m from Anaconda,” he said, “which means I don’t like Republicans, and I especially don’t like Republican yuppies from Bozeman who tell me what to do.”

Mike is old-school union Democrat, but since returning to Anaconda, he’s spent countless hours at the VFW, shooting the shit and talking to vets who don’t necessarily have the same union background or outlook as he does. Like so many other Montanans, he sees what unites him with those vets as stronger than what divides them — and that’s what allows him to have a conversation.

That affinity is possible, at least in part, due to shared whiteness. The diversity in Montana is almost entirely made up of Native Americans, toward whom many Montanans, even those who believe themselves enlightened, self-declared nonracists with Native friends, harbor quietly racist views: A Quist voter told me that the nearby reservation was filled with women who just keep having kids so that they can get government money; a Gianforte voter told me that “who knows what goes on at those reservation polling places.”

Still, there’s a lesson to be learned in Montana — a lesson about the assumptions that both sides make about who’s in their pocket and who’s not. The Montanan perspective, especially on the Democratic side, is that every vote is winnable; as a result, every voter deserves the candidate’s time and perspective. That’s why, as Zolnikov begrudgingly admitted, “Democrats in Montana are good at playing to independents — and Republicans are good at playing to their base.”

For that reason, the Democrats here take little for granted, and remain circumspect about welcoming in an outside influence. Earlier this week, Quist announced that Sanders would join him for four events across the state. Some supporters are ambivalent about his visit: The campaign is already battling the message, best encapsulated in a handmade sign outside of Roundup, that “Quist is a socialist in a cowboy hat.” And while that might sound sexy to non-Montanan voters, “socialist” remains a bad word here, and Sanders’ presence might do more to alienate independents than energize the base.

The Gianforte campaign has no such qualms about embracing national support — or such qualms have been ignored by the national organization, whose commitment to winning the seat can be measured not only by the $2 million it’s spent on the race, funneled via super PACs like the Congressional Leadership Fund, but also the appearances this past week by Donald Trump Jr. and Vice President Mike Pence.

Quist's campaign has begun wielding that decision as ammunition: “They're trying to nationalize this election," Quist told me. "They think they're gonna have the VP come in here and tell Montanans how to vote?” Over the last week, Facebook ads for Quist now declare “Democrats have a chance to win back Montana’s seat in Congress, but a Right-Wing Super PAC is spending nearly $1,000,000 attacking Rob Quist. We can’t let Dark Money buy the Montana Special Election.”

"I don’t like Republicans, and I especially don’t like Republican yuppies from Bozeman who tell me what to do.”

It’s a savvy move: Montanan hostility toward dark money dates to the reign of the copper barons, who controlled elections and squashed union efforts; in 2015, the Montana legislature passed a bipartisan bill that would effectively ban dark money from coming into state elections.

This past session, a different bipartisan bill attempted to increase voter turnout — and save counties money — by making the special election mail-in only. But state GOP Chairman Jeff Essmann sent an email urging Republicans to vote it down, as Democrats have an “inherent advantage” in mail-in elections, which would increase the turnout of “low-propensity voters,” e.g., college students, Native Americans, and the rural poor.

People I talked to, even staunch Republicans, were furious about Essmann’s email and the eventual defeat of the bill, which would’ve saved counties $500,000 statewide. It crystallized all that is wrong with the manipulative, counterintuitive mode of politics gradually infiltrating their state. Essmann’s view was aligned with the national, deeply partisan view of how voting, campaigning, and democracy should work — rather than the Montana way.

Montanans don’t like the barrage of Hillary-style email blasts in their inboxes; they don’t like their radio and television saturated with attack ads; they don’t like self-defeating political maneuvering. “Montanans don’t like to be sold something,” Alexis Bonogofsky told me. “It’s all rhetoric. These national political consulting firms working on both sides, they don’t get it. We know when we’re being sold bullshit.”

At the microbrewery in Helena, I talked to Andrew Person — a floppy-haired guy in his thirties who looks like he could be a school teacher or a raft guide, which is the look of most people who live, like he does, in Missoula. After two terms in the Statehouse, he narrowly lost his bid for re-election; over the course of his campaign, he spent hours talking to people about their political feelings — and about Trump.

“There’s a miscalculation at the heart of the Gianforte campaign,” he told me. “They’re banking on the idea that Trump was popular here. But he wasn’t necessarily popular, so much as Hillary was unpopular. The decision to tie Gianforte to a New Yorker like Trump, or Trump Jr., is a poor one — and a fundamental misunderstanding of Montana conservatives. People outside of the state are trying to examine this election from their existing paradigms, but they just don’t work here. We vote differently.”

If Montana is one of the last places in the United States where voters are inclined to be persuaded, it behooves all of us — analysts, strategists, candidates, organizers — to think about not just what persuades them, but if it’s possible to foster environments, like that in Montana, that make such persuasion possible.

All politics, as the saying goes, is local. But for local successes that add up to national triumphs, it’s not about more super PAC money or Facebook campaigns. Instead, you need more people like Gerry in Great Falls, who doesn’t even have a Facebook account but knows everyone in town and starts conversations at church. You need people like Taylor Brown, whose voice is so well known across the state you could stop a rancher’s house, tell them you’re a friend of Taylor’s, and they’d help you out. You need people like Mike talking at the VFW, and people like Marko, who’s become such a fixture at local meetings about the future of the ranch land that people have taken to calling him “Meeting Marko.” You need grassroots, but you need the actual, genuine, knowing-people sort of grassroots, not the kind thrown around as an abstract conversation in strategy meetings.

That’s hard for outsiders, especially those who have been conducting most of their activism from behind a computer, to hear. Montanans are old-fashioned in many ways, including the reliance on and preference for in-person interactions, and a deep, and oftentimes warranted, suspicion of outsiders. You can call those attitudes traditional; you can call them paranoid. Or you could just call them the beginning of the roadmap for how to actually win in the next national election. ●

Correction: A previous version of this article previously noted that the resort where Quist played a concert is a nudist hot spring. It is a nudist resort with several pools and hot tubs. Gianforte grew up in San Diego, not Colorado.