WASHINGTON — It’s 7 p.m. on Thursday night and a basement conference room at the Renaissance Hotel is filled with Christ’s love. There’s a praise group working the front stage, and even though the seats are only a third full, everyone here is committed to spending the next two hours praying to stop abortion and heal those who’ve experienced it. “Leave your denomination at the door,” the praise leader says, “because we’re all here for one purpose tonight.”

When the crowd breaks into small groups to pray for the appointment of an anti-abortion Supreme Court justice, you can hear the rustle of teenagers — laughing, flirting, yelling — out in the hall. They’re wearing matching hoodies, hats, and/or scarves bearing the name of their high school or church, emblazoned with quotes like “Even the smallest person can change the course of the future” (J.R.R. Tolkien) paired with the imprint of a baby’s feet.

Down the hall, the March for Life Expo Hall is packed with booths for every sort of pro-lifer: There’s an (empty) pro-life Democrats booth, a Catholic college advertising a degree in “Science and Bioethics” that will help build “a culture of life,” a guy who prints pro-life images on the back of your checks, and stands selling shirts with messages like “All Lives Matter,” “I’m So Pro-Life I Must Be Irish,” and “I <3 Pro-Life Boys.” There’s a table for the Radiance Foundation, which put on the worship service, scattered with postcards that double as shareable memes on its website.

What’s on display here is the most branded, visible, and effective part of the March for Life, centered around the idea that “pro-life” can be simply equated with “anti-abortion.” The distilled message can feel irrefutable: Babies deserve to live. And it’s particularly salient now, as the combination of a vigorously anti-abortion vice president and a malleable president have made swift steps to curtail abortion access in the United States and abroad.

The March for Life has never been more visible: In its 44th year, it was covered by more media outlets than ever before, in part because Vice President Mike Pence was there to speak. Donald Trump mentioned the lack of coverage on ABC, going on to tweet about it twice. Pence told the crowd that he was there at Trump’s personal behest, and there was a sense, following Trump’s consternation and obsession with his inauguration numbers, that he wanted the march to be, to use a Trumpian term, “huge.”

Most attendees agree wholeheartedly with the concentration on banning abortion, repealing Roe v. Wade, destroying Planned Parenthood — and, as high school students generally put it to me, “saving the babies.” But many others spoke of an eagerness to break away from the laser focus on abortion, and expand the meaning of “pro-life” to mean “from the womb to the tomb” — an umbrella concept that covers care for refugees, immigrants, the environment, the elderly, the infirm, and the most vulnerable. Put differently, they conceive of the term “pro-life” as mirroring the teachings of Jesus — a posture that’s contrary to many of the policies and proclamations already in place under Trump.

These dissenters want more from the pro-life movement. They want to broaden the conversation, but more specifically, they want to have a conversation — something that’s largely impossible when your brand is fixated on calling Planned Parenthood an “abortion mill.” They want to talk to pro-choice supporters, and women in particular, about what they agree on, instead of being divided over the one issue on which they do not.

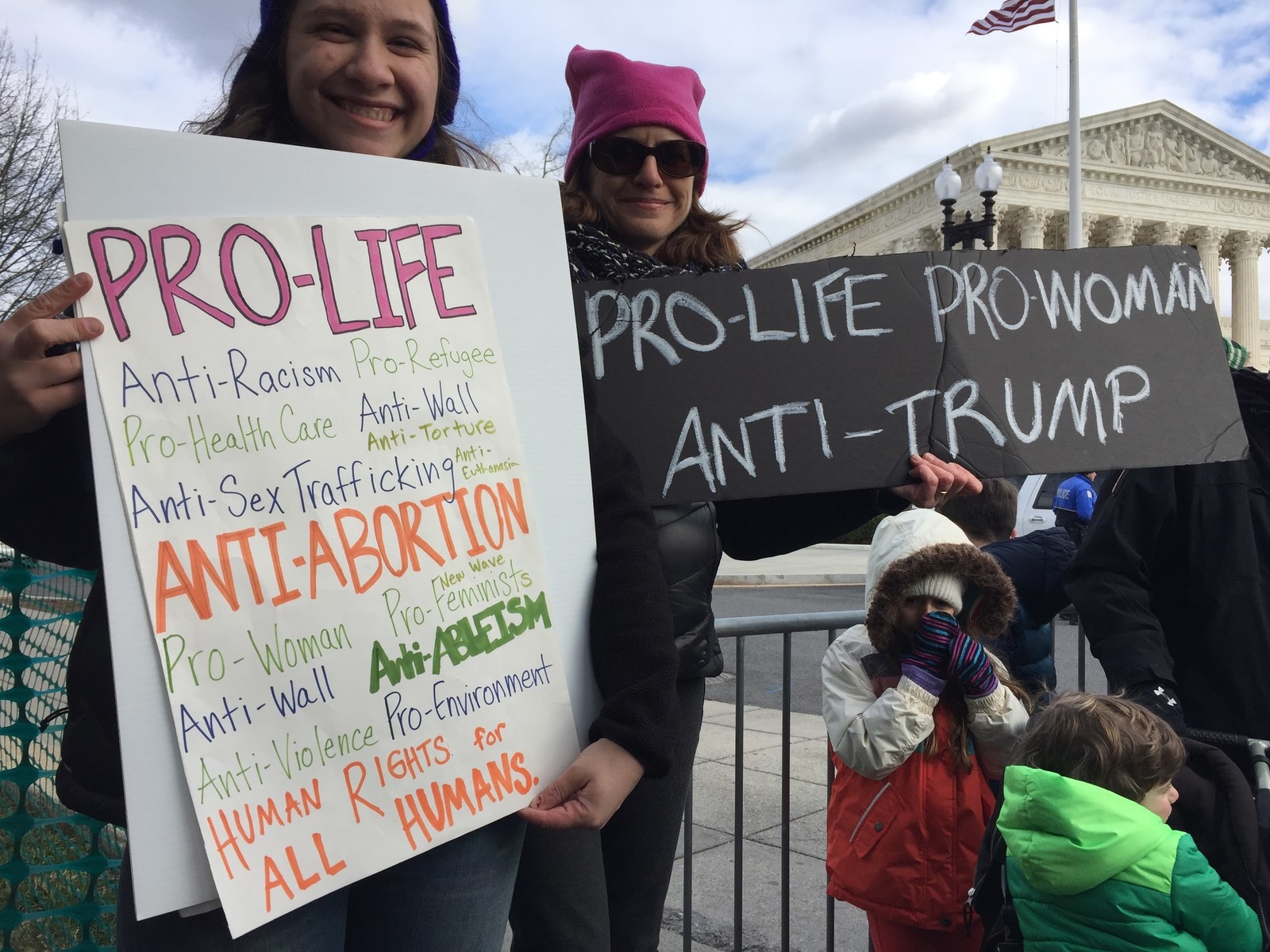

In speaking out against Trump’s other, anti-life policies, these individuals may be damaging the brand that has worked so effectively for anti-abortion causes. But that’s the thing: Their brand isn’t anti-abortion, at least not singularly. They’re pro-life. It’s a semantic distinction, but a crucial one: One ideology fixates on the moment of conception; the other dedicates itself to care of individuals throughout their lives, as well as the planet they inhabit. And that distinction is often lost, especially among those who are pro-choice.

So who are these broadly pro-life people? Students at Catholic colleges. Grown women. Some dudes in fleeces. Franciscan friars and priests. Pope Francis. And they all want to expand the understanding of what pro-life looks like, advocates for, and even rebels against — including our president. As Liz McCloskey, a Washington, DC, resident holding a sign that read “PRO-LIFE PRO-WOMAN ANTI-TRUMP” told me, “Trump wants to look out his window and count all of us here as his supporters. That’s why I made this sign: so he couldn’t claim that we were all his.”

Branding might seem like a callous word to apply to an ideological stance toward what happens once an egg has been fertilized, but there’s no better word to describe the way anti-abortion advocates have spent the last four decades centering and clarifying their message. That message: Every fertilized egg is a baby; if you kill that fertilized egg at any point, for any reason, then you are killing a baby. That includes fertilizations that occur after incest or rape, as well as fetuses with fatal birth defects or conditions that threaten the health of the mother. For many, it also includes fertilizations that take place during the IVF process, but that conversation, like the ones about miscarriages and birth control, is secondary — a potential distraction from the central talking point, which is "stop killing babies."

Babies, after all, are an incredibly persuasive marketing tool. They elicit a strong and immediate emotional response. They induce an incredible amount of empathy. They famously muddle attempts to logically think through scenarios, like “Would you kill Baby Hitler?” That’s part of why babies and toddlers — not awkward tweens — are central to the anti-abortion brand: They force an equation between the act of abortion and the theoretical absence of that child.

Recently, abortion “survivors” — men and women who survived their parents’ attempt to abort them — have become powerful advocates for the movement. Melissa Ohden, who survived her mother’s saline abortion in the 1970s, founded the Abortion Survivors Network, published a book, and criss-crosses the country speaking at conferences and testifying before Congress. She often rhetorically asks audiences a version of, “They want women to have a choice? Well, I want the choice to not be killed.”

Women like Ohden are persuasive, but pictures of them lack the ideological power of a baby face, baby feet, baby hands — all of which take center stage in the flyers, bulletin boards, and T-shirts of the movement. “Save the babies” rang out as a rallying cry during Friday’s March for Life, as high school groups chanted back and forth to one another, “We love babies / Yes we do / We love babies / How 'bout you?” To endorse choice, under this logic, is to hate babies — and in America, if not the world, few things are more unspeakable than that.

If “stop killing babies” is the central message of the anti-abortion brand, then “destroy Planned Parenthood” is framed as the primary means to achieve that goal. Language on the March for Life website and elsewhere refers to Planned Parenthood as a “killing center”; an Instagram post on the Made for Life account frames gold medal gymnast Simone Biles as Planned Parenthood’s “Perfect Target.”

Anti-abortion advocates view Planned Parenthood as the evil overlord of the abortion “industry”; its destruction would be the battle to clinch in the “war” (a term, along with “crusade,” regularly employed to describe anti-abortion efforts). If this language sounds biblical, it’s no accident: Followers believe the fight for babies’ lives, like the fight over Planned Parenthood, is one of spiritual warfare.

In narrowing the movement to a single, easy-to-champion goal and a single means of achieving it, the anti-abortion movement has become a sleek, svelte, and incredibly powerful ideological machine. The simplicity of its message attracts evangelicals and Catholics most of all, but also secular conservatives and those, perhaps without strong political or religious beliefs, who are nonetheless persuaded by the message that babies shouldn’t be killed.

At the ProLifeCon Digital Action Summit on Friday morning — put on by the Family Research Council, whose stated vision is “a culture in which human life is valued, families flourish, and religious liberty thrives” — prominent players in the anti-abortion fight were teaching each other how best to propagate those messages to the masses. A small conference room was set up to livestream on Facebook, where around 250 people tuned in, live, from home (since then, 25,000 people have viewed the video, which has been shared 442 times). Rep. Randy Hultgren (R-IL) outlined the Republicans’ fight to approve the so-called Mexico City policy, telling the audience “we’ve got a window of time we’ve got to take advantage of” and “this is directional — the next six to eight months will dictate what kind of country this will be.”

Hultgren was greeted with applause and graciousness, but the real draw was speakers like Brandon and Brittany Buell, parents to Jaxon Strong, who was born with microhydranencephaly, a form of microcephaly, a neurological condition in which a baby’s head is significantly smaller than others his or her age. The Buells were advised to terminate the pregnancy after an early ultrasound, and were later told their son would not live past the age of 2. The Buells refused doctors' advice, and Jaxon is now nearly 2 and a half — an internet sensation, with over 400,000 likes.

Like Rebekah Buell (no relation), who “reversed” her chemical abortion after changing her mind between the two-day series of medications, the Buells were there to show the power of personal narrative in spreading the anti-abortion brand and belief system. People like the Buells have been sharing their “testimony,” as it’s called in evangelical circles, for decades, but that message travels differently online: Digital pictures and video, spread most powerfully via the mechanisms of Facebook, reach beyond the silos of the already convinced. They function like mini movies-of-the-week, creating melodramas that explicitly and implicitly direct the viewer towards a stance of anti-abortion.

Abortion "survivor" Melissa Ohden knows she has a powerful story. But she also knows it's become even more powerful when shared online. She saw the anti-abortion momentum begin to swell on social media when the Center for Medical Progress (CMP) released “investigative” videos (thoroughly criticized and delegitimized) about Planned Parenthood’s sale of what the CMP called “baby body parts.” (In 2015, a spokesperson for Planned Parenthood said that “women and families who make the decision to donate fetal tissue for lifesaving scientific research should be honored, not attacked and demeaned.”)

“Using social media, we are planting the seed,” Ohden told the audience. “If you’re out doing something pro-life, take a photo and tag yourself!” “I often say, the personal is political.” (She did not acknowledge that this phrase was borrowed from second-wave feminism). “Take an event and connect it back to your own life in a blog post.” Ohden thinks everyone should learn how to use Facebook Live, jump into the comments section of any post on abortion, “share some facts,” and “be willing to mainstream." She herself recently appeared, with great trepidation, in Women’s Day and Good Housekeeping, in order to spread her message outside of her community. “Even the media is capable of being converted,” she said.

Kelsey Harkness, a twentysomething news producer at the Daily Signal (a conservative website funded by The Heritage Foundation), had a similar message. With her videos, she works to tell personal, nuanced stories — like the one, released last week, that interviewed pro-life women who felt excluded from the Women’s March. Harkness relies heavily on infographics: She takes policy statements, reports, and surveys and digs deep to find “that one fact that will shock people.” “Pro-lifers get caught up with feelings,” she said, “and they forget to just show facts” — which, unlike opinions, reach “far more diverse audiences.”

“I applaud you all here today for the diversity of your movement,” Harkness said to a room that was almost entirely white. Outside, the tens of thousands of March for Life attendees were beginning to make their way down to the Mall, the vast majority clustered in groups that had either bused or flown in for the three-day event. Judging from sweatshirts, hats, varsity jackets, and school banners, the vast majority were from Catholic high schools, colleges, and parishes; of the 30-plus individuals I spoke to over the day, all but two were Catholic (one was Lutheran; one was evangelical). The vast majority of people on the ground were white — dotted with clusters of Catholic Latinos and black women.

Catholic groups start mobilizing and fund raising for the march early in the school year, and many students were there for their second or third time. It’s a march, but it’s also an opportunity to go on a trip with your friends, flirt, and visit the big city. (I didn’t talk to or see anyone from major metropolitan areas, other than Washington, DC.) Franciscan University, located in Steubenville, Ohio, gives students the day off; every year, half of the 2,500-person student body attends.

When an event happens every year, with an established infrastructure of dinners, masses, conferences, transportation, and lodging, it’s that much easier to get tens of thousands of people to show up. Speaking to the New York Times, March for Life President Jeanne Mancini was reticent to directly compare its draw to the Women’s March, which had drawn an estimated 500,000 to DC less than a week before. “I don’t think that these numbers are the most important,” Mancini said. “The number most important for us is 58 million, which is the number of Americans that have been lost to abortion.”

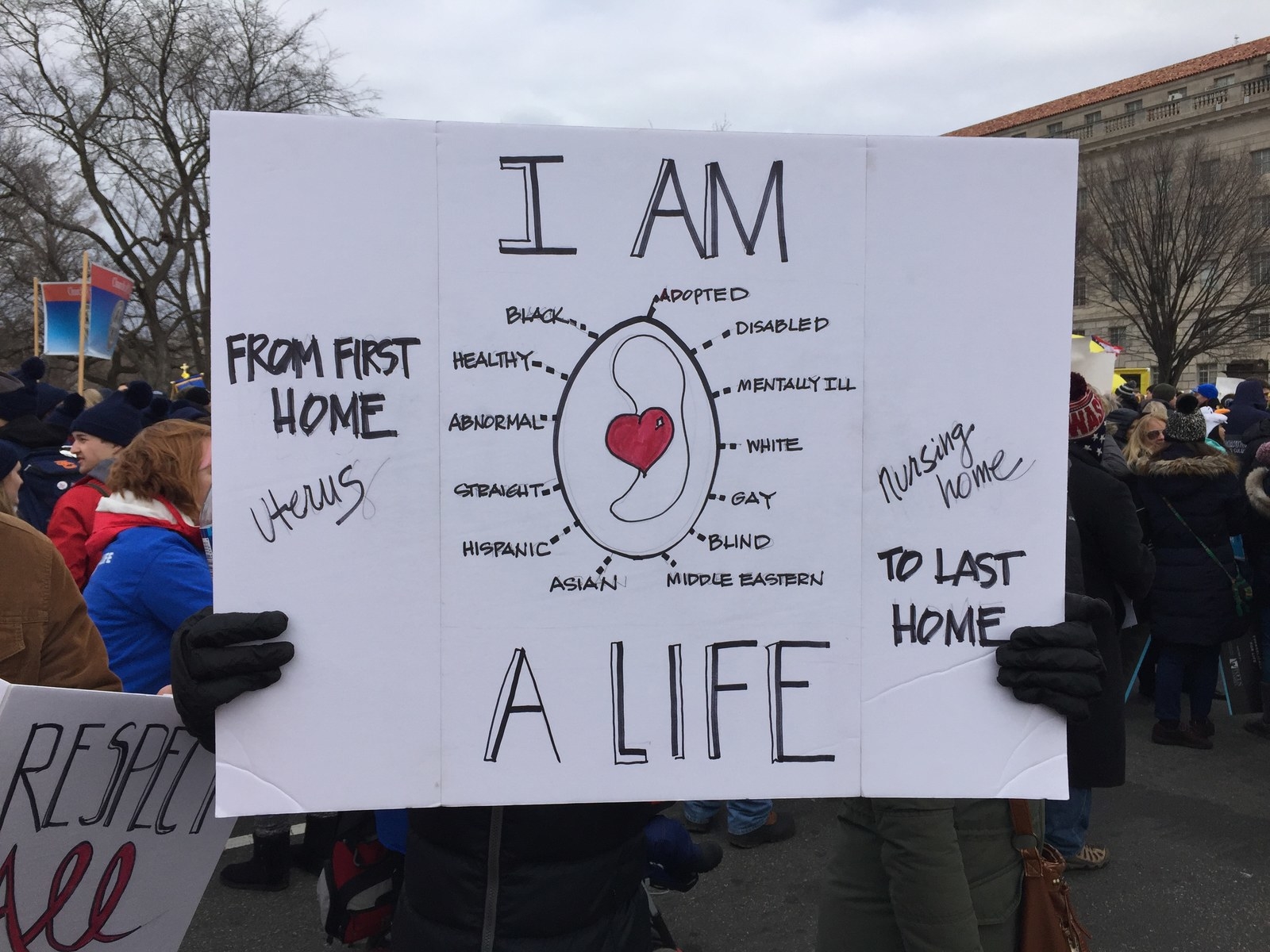

The march was large, but attendance likely numbered, as the organizers admitted, in the “tens of thousands.” Marchers did not clog the streets. There was not the same sense of organized chaos as the Women’s March, in part because the organizers have, again, been putting on the march for many years. There was no pussy hat or similar marker to distinguish participants. They had signs, but the overwhelming majority were not the homemade creations of the Women’s March, but pre-printed by various organizations (the Knights of Columbus, Save the Storks) and distributed on the route to the rally beforehand. Most were simple; some, like the one held by this student from Fort Wayne, Indiana, evoked Martin Luther King: “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.”

Inside the main rally area, the atmosphere was somewhere between a concert for kids and a Christian rock festival. A mash of students jumped up and down to techno Christian music with messages like “We Walk We Walk We Walk We Walk” and joined in on cheers of “We Are / The Pro-Life Generation!” On the outskirts, a middle-aged couple from Waynesville, Cincinnati, leaned against the barriers and observed the energy from a safe distance.

“I see the evilness at stake if we can’t protect the least and most innocent,” Bryan Agee, one-half of the couple, told me. His understanding of “pro-life” was mostly limited to the unborn: “I feel bad for the refugees, but security comes first. We’re doing nothing to help the Christians persecuted in the Middle East. And this is a Judeo-Christian country. I’m sorry, but that’s what it is.”

Closer to the stage, several students articulated a different vision of what “pro-life” meant to them. Shawn, from Fort Wayne, Indiana, told me abortion was the “biggest contributor to the killing of life." Yet for him, pro-life meant “from womb to tomb": Like other Catholics, he’s against euthanasia, but he’s also for welcoming and caring for refugees and the least among us. He added that if we can stop abortion, then problems like sexism and racism will go away. (Next to him, his friend Jordan held an MLK sign, battling to keep it upright in the wind.)

To argue his point, Shawn cited a statistic I’d hear several times, always from white people, during the march and accompanying events: that abortion clinics purposefully target black and Hispanic communities, and that Margaret Sanger was a eugenicist intent on controlling the black population. Abortion, according to this logic, is racist — and fighting abortion is an act of social justice. Hence: shirts, on sale at the expo, with slogans like “Social Justice Begins in the Womb” and “All Lives Matter.” (In fact, less than 5% of all Planned Parenthood health centers are in areas where more than one-third of the population is African-American. Read a fact-check of the Margaret Sanger eugenicist claim here; read about how false Margaret Sanger narratives have been used to shame black women here.)

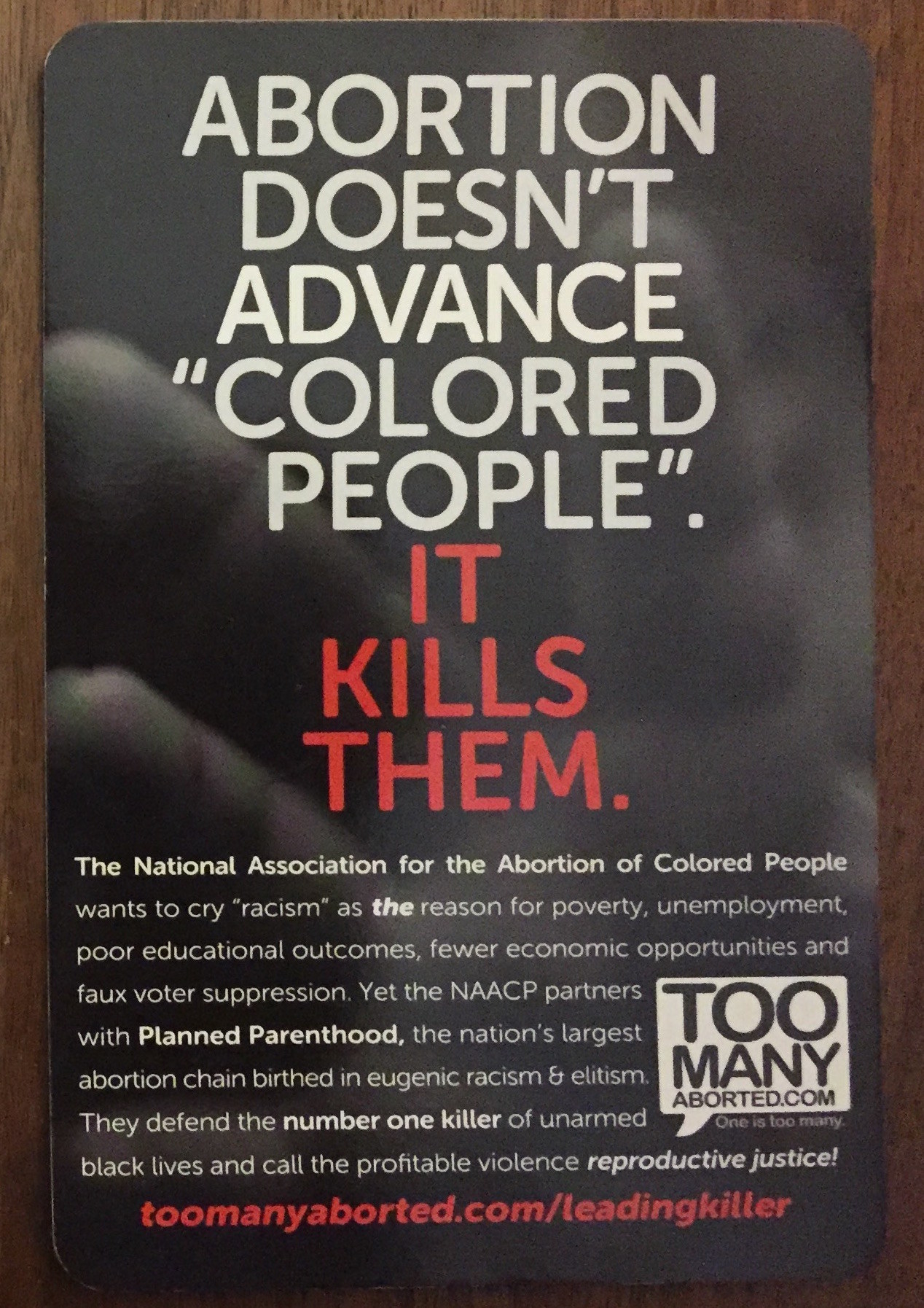

Anti-abortion branding is careful to depict babies of different races; flyers from the Radiance Foundation include the message that “Abortion Doesn’t Advance ‘Colored People.’ It Kills Them” and calls the NAACP “The National Association for the Abortion of Colored People.” Another handout declares “Liberal activists will cry ‘racial injustice when an estimated 258 ‘unarmed’ black lives were killed by police in 2015 yet celebrate when over 317,000 unarmed black lives in the womb are killed every year,” asserting that “abortion is the number one killer of black lives.”

Many of the march participants I spoke to had internalized some, if not all, of this logic — which, like the rhetoric of “true” (read: pro-life) feminism, allows their current project to double as truly progressive social justice.

About an hour into the rally, Mike Pence took the stage and declared that he was there in the name of a president, a man “with broad shoulders and a big heart" who "I proudly say stands for the right to life." Pence took a jab at the Women's March and other protests of the last week, declaring, “Let this movement be known for love, not anger — compassion not confrontation.” I’d heard a similar comparison earlier in the day, when Rep. Hultgren called the Women’s March “really upsetting” and “difficult to even look at,” praising the March for Life for never leaving a mess behind it, unlike what he saw on the Mall last week. A television journalist, there at the march "on my time," told me the Women’s March was too angry — and vile in their use of "that word." "The protesters didn't seem to even know what they were marching about," she said.

The March for Life, by contrast, was figured as peaceful and positive — with attendees who did as they were told. When asked to take out their phones, take a selfie of themselves at the march, and post it to social media, they did so. “Sometimes the media doesn’t report how many people are here,” one of the organizers said. The selfie would serve as its own form of reporting — and a brilliant continuation of the brand.

On the train home from DC, I sat next to a man affiliated with a Catholic institution in New York who’d also attended the march. “I was surprised by what went down at the rally,” he told me. “I thought the election was over. This felt like a political rally.”

A rally that conflated support of pro-life causes with support of the newly elected president. Granted, the beliefs of most past (Republican) presidents have largely aligned with those of the anti-abortion movement, and many elected officials have sent taped or telephone messages to be played at the event. And while Trump’s election has brought newfound oxygen to the movement, it has also scared or frustrated many who have long been a part of it.

Outside of the rally itself, as the masses began to march, that dissent became speakable, if not always visible. Brooklynne, a freshman from Franciscan University who plans to eventually enter the sisterhood, held a sign that read “¼ of my GENERATION IS MISSING." “The Catholic social teaching tells us that life is so important — including the lives of the unborn," she said. "But I’m also very worried about the environment, and what’s going on at Standing Rock, and caring for the elderly, and caring for immigrants and refugees. I disagree with just about everything about Donald Trump. That’s why I feel like I don’t fit in with any of the political parties.” Siobhan, an Irish Catholic from Philly who’d also come down for the Women’s March, said “this particular march was born out of Roe v. Wade. But there are people here like me, who are in their thirties, who are trying to highlight the stuff that everyone can get behind.”

Further down the march, a perky blonde woman named Patricia told me that she, herself, had been an immigrant. “My family is from Slovakia, and were persecuted by the Communists,” she said. “We can’t deny asylum to anyone: The pro-life philosophy includes welcoming refugees. To be anti-refugee is to be anti-American.” She’s a professor at Catholic University, just down the street, and teaches sustainable architecture. “So I’ll be here at the climate march, protesting Trump, too.”

For Patricia, the pro-life argument falls apart when it’s not applied consistently. That includes IVF (she believes in embryo “adoption”), advocating for children in foster care, and paying attention to racial inequities. “You can’t just protect white middle-class babies from being aborted,” she said. Patricia wanted to come to the Women’s March, but several anti-abortion groups were disinvited as official affiliates, and she didn’t know if she’d be welcome. “We absolutely to keep having these conversations, though," she said. "Not shouting, but talking — talking is a civil method towards unity.”

A quarter mile down the road, a group of Franciscan friars from Saint Camillus in Silver Spring, Maryland, stood in long brown robes on the side of the road, hoisting a banner that read “Support a Consistent Ethic of Life,” a red X crossing out the words “Abortion, Destruction of Earth’s Ecosystems, Injustice, Nuclear Weapons, Pandering to Fear, Racism, Social Inequity, and Torture.” “We decided to stand here in hopes those passing by would see it and engage in a moment of contemplation,” one of the friars told me. “The consistent ethic of life is about the seamless garment of the gospel. Pope Francis has said this — you can’t just be pro-life in the womb.”

“ISIS is against abortion!” Father Jacek Orzechowski piped in. “And they’re not pro-life!”

“The political expediency of certain goals cannot trump the integrity of the gospel,” Orzechowski continued. “We have to be consistent, and that includes our posture towards refugees, social injustice, all of these things,” he said, gesturing to the banner above. “Yesterday I was meeting with two DREAMers who were so scared of what’s to come. Tearing families apart is not pro-life. What kind of pro-life is sending a father away from his family? Jesus, Mary, and Joseph were refugees, too — and they, too, were fleeing violence.”

At that moment, a black woman came up to the friars and pressed a medallion into one of their hands. “Thank you so much for being here,” she said. “It’s hard for me to be here because of some of the things listed up there on that banner. But the Franciscans get it.”

The march passed massive billboards depicting graphic, bloody scenes; one, featuring a demon holding a baby and the declaration that “Abortion Is Child Sacrifice,” was accompanied by a loudspeaker blaring a loop of a wailing baby. Parents shielded their childrens’ eyes; teens audibly said “ew, gross.” This was not part of the March for Life brand, and several men went up to the people manning the billboards to complain. “Do you think you’re doing God’s will right now?” one asked.

As the march neared its end point at the steps of the Supreme Court, I spotted a man with a bushy beard and a stocking cop with a sign that read “PRO-LIFE NOT PRO-TRUMP.” “I can’t tell you how many people have come up to me and said they like my sign,” he told me. Nearby was Liz McCloskey, the woman holding a “PRO-LIFE PRO-WOMAN ANTI-TRUMP” sign. "People who value life also take issue with Trump," she explained. "And they take issue with Trump because he values very little.”

“That’s the problem with being a single-issue voter,” she continued. “No one can be completely consistent in how they vote. I’ll never find someone who values the complete ethic of what I believe. But it does a disservice to women’s issues to be so focused. Abortion is not going to become illegal. It’s just not going to happen. We’re having the wrong conversation. Why don’t we talk more about how we reduce it? How do we keep it legal, safe, and also that thing that’s seemed to have dropped out of the conversation, rare?”

“The national conversation about abortion is so impoverished,” she said, shaking her head. “And I mean that on both sides.”

A twentysomething woman cut across the crowd. “Oh my god, can I get a selfie with you?” she asked. She held up her own sign, with its call to be Pro-Life, Anti-Racism, Anti-Wall, Anti-Ableism, Pro-Environment, Anti-Sex Trafficking, and Pro-Health Care, and smiled wide, framing the Supreme Court in the background.

Earlier in the day, Pence told the audience that “to heal our land and restore a culture of life, we must continue to be a movement that embraces all, care for all, and shows respect for the dignity and worth of every person.” It's a statement of basic American values — one I’d heard from several of the marchers I spoke with, espousing a broad sentiment that, along with "don't kill babies," had underpinned the movement’s brand for years.

But I also heard that idea countered, in ways large and small, throughout the day: when a speaker at ProLifeCon told the person sitting next to her that she'd just returned from San Francisco with a cold, “but thank God that's all I caught”; when a college student from Alabama showed off a sign featuring Pepe the Frog, avatar of the so-called alt-right and white nationalism, with the slogan “wouldn't let me be a papa so I stayed Pepe”; and when Brandon Buell proclaimed, “We’re not just pro-life ... I'm also anti-gay, which is now designated as a hate group.” But I heard it most forcefully as the marchers returned to their hotel rooms, wind-burned and hoarse, and the White House announced an executive order, banning travel from seven majority Muslim countries, including refugees from Iraq and Syria.

Under Trump, the anti-abortion brand has never been stronger — but the tenets of a full pro-life movement are increasingly under siege.