Since the election, Sherman Alexie’s been getting death threats. He got so many leading up to his commencement speech at Washington’s Gonzaga University in late May that he considered canceling his appearance. “I’m a Commie liberal brown dude,” he told me on a sunny June day in Seattle, where he’s lived for the last 20 years. “I don’t believe them, but it still creates such fear — like with the candidates dropping out of races because of death threats. I don’t think it would happen to them, and I don’t think it’s going to happen to me. But I do think that a brown-skinned liberal activist is gonna get assassinated. Five minutes earlier, Alexie was talking about his new memoir, You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me, which had just come out that morning. His face had appeared on the cover of the New York Times Sunday arts section, with a photo of him looking reflective. A friend texted him, “You look like Javier Bardem’s having a bad day.”

Recounting the text, Alexie burst into a deep belly laugh that reverberated through the entire coffee shop. His friend isn’t wrong, though: Alexie, who recently turned 50, has developed something of a silver fox aesthetic. When we met, he was wearing a gray granddad cardigan and khakis, but at a reading, the next night, he wore a beautifully tailored suit — the sort of thing you rarely see in fleece-wearing Seattle.

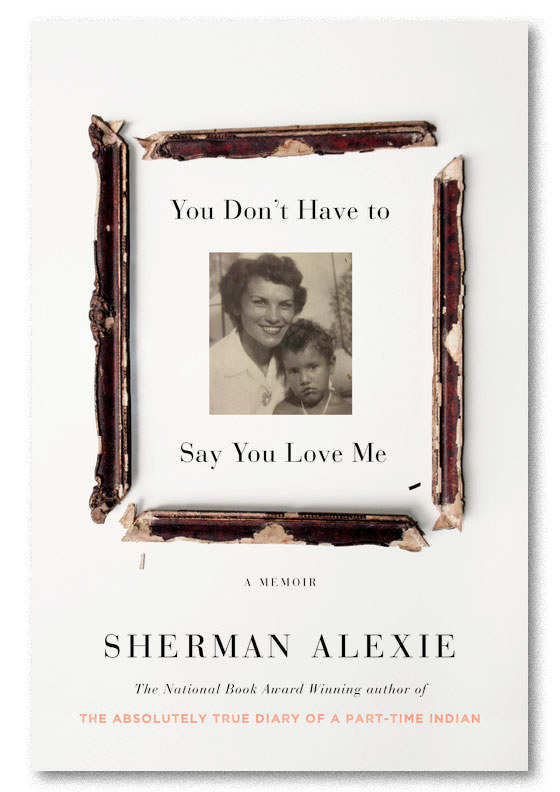

Today, Alexie’s baseline is anxious. “I’m a wreck,” he said. “I barely slept last night. Just constant nightmares of things crushing me.” While this might be his 26th book — and the vast amount of his fiction, poetry, and filmmaking has been influenced, in ways overt and subtle, by his own life — it’s his first true memoir. And it’s about his mother, Lillian, a strong and fearsome woman he describes as “the lifeguard on the shores of Lake Fucked.”

Lillian ensured Alexie survived his life on the Spokane reservation, but she could also be a cruel, exacting, and profoundly unloving mother. It’s an exquisite, wrenching book — and one of the fullest portraits of an imperfect woman I’ve read. “She was a great human being, who had greatness in her. She could’ve led the tribe,” Alexie said. “My mother was a great woman — but not a great mother.”

The seamless transition between personal mythology, profanity, self-flagellating humor, and politics is classic Sherman Alexie. It’s what’s earned him a National Book Award along with dozens of other honors, what’s sold hundreds of thousands of books and put him on classroom reading lists across the country. It’s what’s made his semiautographical novel The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian one of the most challenged books in American history. It’s what’s made him a huge speaking draw and earned him death threats, along with the dubious distinction of being the most prominent American Indian in American culture today.

Dubious because when you’re the most prominent representative of any group — racial, political, regional, or tribal — you’re also called upon to comment on anything and everything that affects that group. “There’s a desire to focus on the 'Native' part of my hyphenate at the expense of the 'American' part of my hyphenate,” Alexie said. “Even we who are Native don’t portray ourselves as complicated as we are. Because the rewards in the Indian and non-Indian world are for being the kind of Indian that’s expected.”

“For all the damage my mother did to me, the thing she gave me, and that has saved me, is the arrogant belief that I deserve to live.”

Meaning: the kind of Indian who looks, acts, and writes like a 19th-century stereotype of an Indian. Which is to say, a Dances With Wolves Indian. An Indian with long braids, an Indian who speaks their own tribal language and dances at powwows. An Indian who speaks in vaguely mystical verses about Mother Earth and the Wind, who stares off into the distance, and who lives on the reservation, who is humble. Who certainly doesn’t say "fuck," or talk about anti-gayness on the rez, or write a YA book that talks about masturbation. That Indian doesn’t live in a city and publicly criticize tribal politics. (Alexie doesn’t think of the term “Indian” as a pejorative; he doesn’t refer to himself or members of other tribes as “Native Americans,” and says “the only person who’s going to judge you for saying ‘Indian’ is a non-Indian.”)

Sherman Alexie is not — and has never been — the Indian you expect. He thrives when he pisses people off. “I am the author of one of the most banned and challenged books in American history and that makes me giddy with joy,” he writes in You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me. “But, all in all, I am most gleeful about inciting the wrath of other Indians.”

He says things in interviews, like this one, just to see how people will react. He tells a joke whenever he gets close to a place of pain. He knows that the flip side of arrogance is vulnerability. It’s all generative, all grist for the mill.

Alexie said he inherited that arrogance from his mother. “For all the damage my mother did to me,” he said, “the thing she gave me, and that has saved me, is the arrogant belief that I deserve to live.” Arrogance isn’t an admired trait in the Indian world, but when Alexie teaches, he tells his students to embrace it — and to be unafraid of anger. “I didn’t survive all the stuff you’re gonna read about in this book because of humility,” Alexie said. “I survived because I’ve been pissed off for 50 years.”

At this point, 30 years into his own career, Alexie has forgotten the specific contours of his own mythology. Between the stories he’s told about himself, what others have interpreted from his semiautobiographical books, and what’s become canon in the hundreds of interviews and profiles is something like the truth. Born to a Spokane Indian mother and a Coeur d’Alene Indian father in 1966, he grew up on the Spokane reservation — a 237-square-mile piece of land where the only town numbered around 900 people.

As an infant, he endured multiple surgeries to deal with congenital hydrocephalus, or “water on the brain”; he had seizures until he was 7, he wet the bed, he got teased for his slightly large head. His parents were both alcoholics, but when Alexie was young, his mother stopped drinking entirely — a decision Alexie credits with ultimately saving his life. He had four siblings. He read voraciously. He loved basketball. He used a sack of butter knives he bought from a thrift store to wedge in his door to protect himself from predators during long, drunken parties at his parents’ house.

When Alexie reached junior high, he began planning his escape from the reservation. The first stop: the white school on the edge of the reservation, where, as Alexie tells it, “the only other Indian was the mascot.” In Reardan, the rural farm town where he went to high school — sometimes hitchhiking, sometimes walking the 20 miles between home and school — he crafted himself into an all-American Indian, which is to say, a part-time Indian: Among his all-white classmates, he was prom king, and president of the Future Farmers of America ("I raised a pig!"), and captain of the basketball team.

He swallowed the sadness of overt racism from the parents of white girlfriends, and subtle means of control, like getting called “Chief Gayfeather” on the debate team. “Because of my emotive personality, because of my artistic side, because of who I am now and who I’ve always been, they had to give me a racist, homophobic label,” Alexie told me. “It was like, ‘We know you’re this cool person, but we’re also made uncomfortable by you, and we need to have some power over you.’”

“I rolled with it,” Alexie continued. “That’s self-denigration, self-preservation. I was trying to save my life. My rebellion ended up having to just be better than everyone at everything all the time.”

Alexie won a scholarship to Gonzaga where, after years of working toward perfection and “part-time Indianness,” as he’d later call it, he fell apart. He took his first drink of alcohol, which led to many drinks of alcohol. He dropped out, went to Seattle, went back to the rez, and eventually found his way to Washington State University in Pullman, where an English professor first introduced him to writing by other Indians — and the poem “Elegy for a Forgotten Oldsmobile,” by Adrian C. Louis, with a line that convinced Alexie to start writing: “Oh, Uncle Adrian, I’m in the reservation of my mind.”

A small Brooklyn press released his first book, The Business of Fancydancing: Stories and Poems, in 1992 — which ended up featured in the New York Times. From there, it was something like instant literary fame: He sold a book of short stories, The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven, and a novel, Reservation Blues. He was heralded, as he put it to me, “as a miracle.”

“It was like, ‘You came out of nowhere, you’re a star child!’” Alexie imitates. “‘Look at his storytelling tradition, the oral tradition, it comes from his grandmother!’ Nah, I just did debate in high school, and stand-up in college.” He wrote more novels and short stories and poems; he wrote the screenplay for Smoke Signals, the first film made with a totally Indian cast and crew, which won the Audience Award at Sundance in 1998. He married a Hidatsa/Ho-Chunk/Potawatomi woman he met while judging a writing competition. His work was likened to Richard Wright's Native Son and declared one of the New Yorker's “20 Best Young Fiction Writers in America.”

The work that followed oscillates between revisiting the concerns of the reservation and expanding the conception of what an Indian can be. Ten Little Indians is filled with stories of men trying to figure out jobs and relationships and sex and class off the reservation; the film The Business of Fancydancing, which Alexie wrote and directed, tells the story of a gay Indian poet living in Seattle and working through his ambivalence about producing work whose primary audience is middle-class white ladies.

As Alexie put it, the people who didn’t like him on the reservation when he was a kid — the ones who teased him and beat him up, either for being different or for leaving the rez — are the same people who don’t like him now. When he tried to shoot Smoke Signals on the Spokane reservation, the tribal council refused.

Some Native Americans use the metaphor of the crab in the bucket to explain the anger and resentment directed toward those who move off the reservation: If you can’t or won’t get off yourself, you try to keep everyone else in the bucket with you. But in You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me, Alexie describes it differently:

Scholars talk about the endless cycle of poverty and racism and classism and crime. But I don’t see it as a cycle, as a circle. I see it as a locked room filled with the people who share my DNA. This room has recently been set afire and there’s only one escape hatch ten feet off the ground. And I know I have to build a ladder out of the bones of my fallen family in order to climb to safety.

The book moves seamlessly between poetry and prose and somewhere in between, circling through Alexie’s childhood and late adulthood, his parents’ lives and how he did and did not fit within them, cornering revelations and lies like wounded prey. But it’s passages like these that catch the heart and blow it open.

The death threats directed at Alexie are relatively new, but they’re also linked to at least 20 years of being political in public. He’s a regular fixture on KUOW, Seattle’s local NPR station; he’s written incendiary columns for The Stranger and editorials for the Times. Back before he quit Twitter (“I got sick of my own id”), he’d say things like, “My 2017 is gonna be white liberals shocked about white racism & white conservatives denying white racism exists. Just like every other year.”

Alexie’s politics don’t spring from some newly awoken anti-Trump sentiment. He was anti-war and anti-Bush throughout the 2000s, and a voracious reader of political thought — he subscribes to dozens of magazines; his current favorites are Pacific Standard and the leftist quarterly Jacobin — but he’s also sought out conservative news and radio. There was a time when he purposefully made friends — in person, via email — with people on the right so that he could, in his words, “hear them in a sane way.”

But this year’s election changed all that. “To watch these sane people, who I knew to be sane, go utterly crazy,” he said, shaking his head. “Trump is a disease. He is a contagion.”

“You know what's happening: The whole country is becoming a reservation."

Even though he was ensconced in liberal Seattle, Alexie knew how the election would go down. “My friends were mad at me, but I knew,” he said, shaking his head. “I wasn’t shocked and I’m still not shocked. It’s total exploitation, with everything up for grabs. Health care, gone. Destroy the environment in search of more profit. State-sponsored violence. Targeted incarceration. You know what’s happening, though: The whole country is becoming a reservation.”

Like many people of color in the post-Trump world, Alexie has found himself serving the role of confessor. White people ask him, “What can do I, how can I be better?” “Don’t cry on my shoulder,” Alexie said. “Get your ass to work. There’s still a lot of apologists in the white liberal world, people apologizing for their family and friends. And I tell them, 'dump ’em.'”

This philosophy stems from sex columnist Dan Savage’s advice on homophobia. “He always says that the only political power you have with your friends and family is the power of your presence or absence in their lives,” Alexie said. “So I’ve dumped friends. I’ve dumped my conservative friends, but I’ve also dumped fundamentalist Bernie Bros. Really what’s happened is I’ve dumped a lot of men in my life.”

For Alexie, there are two groups responsible for Trump’s win: those who yearn for an America that never existed, and those who yearn for an America that can never exist. “You can’t have Sweden here,” Alexie said. “It’s much smaller and really white — and has real problems with racism. I mean, Seattle is Sweden! Extremely liberal, progressive, and very white, with a strong undercurrent of racism.”

The week before, members of the alt-right and anti-fascists (or Antifa, as they’re known) had converged for dueling protests in downtown Seattle. Watching it on television, Alexie couldn’t tell which side was which. “They were all done up in fake-ass military gear,” he said. “It looked to me like universal assholery. Contrast that to the Women’s March, which was also angry and scared — but constructive, and loving, and organized! And nobody punched anybody.”

There’s a strong overlap between the women of the anti-Trump resistance and Alexie’s readership, which is primarily composed of college-educated white women. Unlike some male authors (see: Jonathan Franzen) who worry that a female audience will feminize their art, and thereby delegitimize it, Alexie embraces his readers. “They pay my mortgage!” he said. “But they’re also just more open to actually crossing boundaries. They have that perfect combination of privilege — because of their whiteness — and oppression, because they’re women. They’re at the forefront of every battle, and they come into it with both strength and weakness, with both power and pain.”

When he performs, Alexie often pokes gentle fun at the white people who are so enthralled with him — “you non-Indian lovers of Indians, you romantic fools” — or Indians in general, in the current political moment. “It’s cool to be Indian,” he’ll say. “We start a protest and Hollywood shows up!” Alexie’s referring, of course, to Standing Rock — and Shailene Woodley’s presence and arrest. But for all the show of solidarity at and around Standing Rock, Alexie maintains that Native Americans have no real allies.

“It was an astonishing cultural event,” Alexie said, “and I don’t think the world even understands what a massive deal it was for all of these tribes to be together in this one place. But as for allies, it’s all surface. We are a fashionable cause. And a different tribe would not have had the same response: the Sioux look soooooo Indian. They’re the Indians that all the movies have been about. Their physical appearance is the image of Native Americans. Plus, you know, the Sioux have gotten completely fucked.”

According to Alexie, Standing Rock worked — and became such a national beacon and rallying point — because of current climate change politics. And Natives, he said, are beautiful metaphors and symbols of those politics. But Alexie knew that the fight was already lost: “Even if Hillary had won, the pipeline would still be flowing.”

There’s talk that Bears Ears — a national monument and recreational area home to thousands of sacred sites in southern Utah, recently recommended for downsizing by Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke — will become the next Standing Rock. “The administration is doing something stupid again,” Alexie said, with a smirk. “They’re going after a monument that white people love. They should go after the monuments that white people don’t give a shit about.”

Still, he’s certain there will be another violent clash — if not at Bears Ears, then somewhere else. “There’s gonna be a Kent State,” he said. “Standing Rock was leaning toward that — towards a massacre. Standing Rock gave Natives a sense of purpose, it gave them power, and it gave them visibility. It was a confluence of liberal environmental politics and our own love of war. We’re a warrior culture! And here’s this chance to fight for the land? It’s empowering! It gives us power over centuries of trauma — and the chance to finally fight back.”

“My primary power is for the weird brown kid who gets to know that they’re not alone.”

Alexie donated items, helped fundraise for legal help, and posted regularly about #NoDAPL on his social media. But for many, it wasn’t enough: They wanted more from the most visible Native American in the world. “Everyone wanted to have me come on their show, or be interviewed. But it’s not my tribe, it’s not my reservation, it’s not my fight to be a spokesperson for,” Alexie said. “I was in this dilemma of honoring Native culture and Native politics by not speaking. If I would’ve spoken up, I would’ve angered one group. And by not speaking up, I angered this other group — mostly composed of white people.”

There’s a fantasy, Alexie thinks, that fame means power — or the ability to change things. “It depresses people to think that I have exactly the same vote as they do — that I don’t have power to change oil company policy, that I have not changed a single human being’s mind about environmental policy.”

What about soft power, then? The idea that his books can humanize Native Americans — and in so doing, quietly change people’s racist minds? “Listen, I’ve never met a conservative person whose mind has been changed about Natives,” Alexie countered. “I’ve never received that letter. My primary power is for the weird brown kid who gets to know that they’re not alone. I don’t mean to undervalue what I do: Me and my art can make some people feel less lonely; I exist because of the books that made me feel less lonely. We don’t have power. Something like 'poets against Trump' doesn’t change minds. What we can do is help people get through another day.”

Initially, Alexie was scared that his memoir would be labeled as misogynist, simply because he portrayed his mother as he experienced her, not through some beatifying lens. It’s difficult to predict how the internet will react to a piece of art, given what Alexie calls “the microscopic political climate” and the endless, only occasionally generative debates about whether or not a text is feminist. “Everything is such a purity test,” he said.

But to call You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me misogynist is to profoundly misunderstand the way good biography works. “You know, white guys write these books about presidents, or about Custer — and these really complicated men get really complicated books,” Alexie said. “Women don’t get complicated books. When women write their own stories, those are complicated. But not biographies.” In books as in film and television, women rarely get to be the antiheroes of their own stories.

What Alexie achieves, then, is a portrait of a full and flawed woman — while vividly rendering the myriad forces that made Lillian the mother she was. It’s an exercise in both psychology and sociology: a study of rape culture, a history of the physical and sexual abuse at Indian boarding schools, an acknowledgment of the targeted eradication of a culture, a language, a way of life.

It’s a declaration that reservations were, as Alexie puts it, originally created as concentration camps — and that that remains their primary, if sublimated, purpose. It is a study of a woman and it is a study of the culture that made her, and how both, in turn, made Alexie.

The most urgent and lingering sections of the book convey the bleak reality of those forces on a population of people. On the legacy of sexual abuse at Indian boarding schools, where Alexie’s relatives were punished for any attempt to sustain their Native culture, Alexie writes: “When people consider the meaning of genocide, they might only think of corpses being pushed into mass graves. But a person can be genocided — can have every connection to his past severed — and live to be an old man whose ribcage is a haunted house built around his heart. I know this because once I sat in a room and listened to dozens of Indian men trying to speak louder than their howling, howling, howling, howling ghosts.”

Depending on your familiarity with Native American history or Alexie’s work, sections like this — as well others detailing the lingering effects of a uranium mine that seeped into the family’s swimming hole, or the way that Alexie was forced, as a child, to assume “stress positions,” officially considered tools of torture, when he misbehaved in class — might be unsurprising. But what Alexie does with this book — what he’s always done, moving from medium to medium — is translate that history in a way that makes it impossible to ignore.

Take his section on the creation of the Grand Coulee Dam and the subsequent eradication of wild salmon, the spiritual and nutritional cornerstone of the Spokane Tribe: “What is it like to be a Spokane Indian without wild salmon?” he writes. “It is like being a Christian if Jesus had never rolled back the stone and risen from his tomb.”

Growing up in the West, I’ve read and internalized the effects of the massive Grand Coulee Dam — on the environment, on business, on people whose lives changed radically in the aftermath. But it took Alexie’s book for those effects to move from the abstract to an emotional wallop, with a sentence so devastating it approximates, in whatever small way, the wound it describes.

Alexie’s portrait of his mother reflects a decades-long commitment to what we now call intersectionality. Just as there is no discussing his mother without also discussing the way that women, and Indian women in particular, have fought for their own survival, for Alexie, discussing what it means to be Native also always means talking about class, and sexism, and homophobia.

He especially loves disabusing people of the “liberal progressive Indian myth” and underlines that the political divide that afflicts the rest of America — between the urban and the rural — also cuts through the Native population. “Reservation Indians tend to be pro-gun, pro-life, pro-prayer in schools, pro-war, and anti-gay,” he writes. “I’m amused when liberal white folks go all gaga over rez Indians.” In other words: “Indians are a bunch of rednecks.”

“Everyone knows Sherman as a Native American author, but I think his writing about class is in many ways underrated,” said novelist Jess Walter — who grew up poor on the outskirts of the Spokane reservation. “He doesn’t have an MFA. He went to state schools. And a lot of times when you’re reading an author whose ethnicity you don’t share, they went to Brown and then got their MFA at Iowa. But Sherman writes from a very different place.”

Revisiting Alexie’s work always makes me homesick to my stomach: How lucky am I, to have such a poet for such a place we’ve both come to loathe and love?

And that place — the heart of the rural mountain West — is a place very few people write about. “There aren’t many writers from Washington,” Alexie told Neko Case in a 2012 Believer interview. “And even fewer who speak the language of kids who grew up in poverty there, and probably less than a handful of those speak the poetry of our region. ‘Our’ trees are not ‘their’ trees, if you know what I mean.”

As someone who grew up just a few hours from Alexie’s reservation and went to summer camp just over the county line, I know what he means. I read Alexie’s work growing up because I had a college-educated white mother, but also because no one else seemed to write about the sort of people I knew in rural Northern Idaho: poor people, bigoted people, anti-gay people, Native people, Western people. Angry, frustrated women; drunken, self-defeated men; hopeful and weird misfit kids like myself.

When I was young, I watched Smoke Signals a dozen times because it was the first time I’d seen my landscape depicted onscreen — the dusty sagebrush interspersed with towering pines, the bleak but beautiful and everlasting roads to nowhere. Revisiting Alexie’s work always makes me homesick to my stomach: How lucky am I, to have such a poet for such a place we’ve both come to loathe and love?

Alexie is renowned for his readings, which are essentially one-man tour-de-force performances. He gets paid handsomely to appear at colleges and colloquiums, to give keynotes and capstone lectures. But after his mother’s death — and after surgery, last year, to remove a tumor on his brain — he took a purposeful sabbatical from the circuit and its psychological tax. He quite literally needed to rest his brain.

For this tour, he’s doing what he often does: hitting the big liberal coastal cities, while also appearing in the smaller cities, where few authors go, but that are close to reservations: places like Albuquerque or, for the first time, Tulsa. But the first appearance was on Alexie’s home turf, in front of a sold-out crowd at Seattle Town Hall — a stately old Christian Science church where, on a Wednesday night, the standby line wrapped long around the building.

“It’s a terrifying time to be an American, and it’s a terrifying time to be a citizen in the world.”

The crowd, like so much of Seattle, was very white. But Town Hall, a nonprofit, also prices its tickets to make them accessible (read: $5 a piece) to those who don’t fit the typical cultural-event demographic. In the wooden pews that fill the sanctuary, there were hippie punks and Native kids, grad students reading political theory and white-haired couples holding hands. A dad-looking guy snuck into the back pew at the last minute: Turns out he’d met Alexie playing basketball at Gonzaga back in the ’80s.

“He’s written books that piss off provincial school districts across the land,” the announcer proclaimed. “But he’s ours, and we love him.” Alexie took the stage, made a self-deprecating joke, and the laughter — his own infectious laugh, the audience’s in response — bounced off the walls of the church like a rowdy hymn. “In real life and in the book,” he said, “when I’m nearing the pain I tell a joke,” and then proceeded to tell a 15-minute-long account of the grief poop he took at the funeral home after his mother’s death.

“It’s a terrifying time to be an American, and it’s a terrifying time to be a citizen in the world,” he told the audience. “So I’m gonna read you something very sad.”

That piece — a poem that beats from the heart of the book — is simply titled “Eulogy.” “My mother was a dictionary,” he began. “She was one of the last fluent speakers of our tribal language. She knew dozens of words that no one else knew. When she died, we buried all those words with her.”

Alexie’s voice broke. He bowed his head slightly, and something raw and guttural and soblike escaped him and floated to the ceiling.

He read on, his words swimming past and through the audience, like so many salmon, like so much loss, like the culmination of years of grappling with what it means to be the Indian that no one around you expected:

My mother was a dictionary.

She knew words that have been spoken for thousands of years.

She knew words that will never be spoken again.

I wish I could build tombstones for each of those words.

Maybe this poem is a tombstone.

My mother was a dictionary.

She spoke the old language.

But she never taught me how to say those ancient words.

She always said to me, "English will be your best weapon."

She was right, she was right, she was right. ●