What makes an event, an action, or a person “scandalous”? The designation has always been yoked to the conservative mores of the time; as those evolve, so does what qualifies as scandalous behavior. In the past, women weren’t allowed the freedom to dress in certain ways, or be in certain spaces; now they are, as society has become more liberal and accepting. As have attitudes and ideas about gay and trans people, mixed-race relationships, and certain types of drug use. In many cases, what used to be scandalous — and, once made public, enough to eject you from society — has now become accepted, tolerated, or normalized.

What happened with Harvey Weinstein is different. Weinstein’s behavior, like that of so many other men in Hollywood, has long been acceptable. And though it wasn’t necessarily publicized, his attitude toward women — as objects for his manipulation and disposal — was built into the DNA of Hollywood.

Dozens of classic Hollywood stars and directors, including Clark Gable, Errol Flynn, and Alfred Hitchcock, have been accused of sexual assault or abuse. Maureen O’Hara, Marilyn Monroe, Kim Novak, Dorothy Dandridge, Loretta Young, Judy Garland, and dozens more were subjected to regular harassment and manipulation during their careers. The “casting couch,” a euphemism for male producers and directors demanding sex in exchange for a role in a film, emblematizes the overarching power dynamic long understood within the industry: Men took what they wanted; women played by or otherwise endured those rules if they wanted to succeed. Some may have viewed the actions of these men as gross or unspeakable, but they were still normalized: That’s just the way things are.

Many of those accused of harassment, as well as those who came to their immediate defense, admitted as much. Hollywood has always been a boy’s club, their explanations went; the accused shouldn’t be judged for failing to catch up with contemporary standards of decency. Weinstein-like behavior only became scandalous via investigative journalism, which transformed rumor into on-the-record accounts, and grouped those accounts in a way that established a pattern of behavior. Taken out of the framework of isolated stories by “bitter” or “failed” actresses, they became a matter of public record: documented sightings of a real monster, not just dark fairytales whispered among women.

And the revelations kept coming. Five days after the New York Times first reported on the allegations against Weinstein, a second story, detailing even more extensive and elaborate types of abuse and harassment, appeared in the New Yorker. It was followed by weeks of follow-up stories on, as one New York Times headline put it, “Harvey Weinstein’s Complicity Machine.” First-person essays and accounts from Salma Hayek, Lupita Nyong’o, Brit Marling, Molly Ringwald, and Kate Beckinsale added to both outlets’ reporting. As of this writing, more than 80 women have come forward with their own stories of harassment, abuse, and rape.

But it didn’t stop with Weinstein. In the two months since the reports about him went public, dozens of men within Hollywood alone have been accused of or admitted to different levels of inappropriate behavior, including Kevin Spacey, Dustin Hoffman, director Bryan Singer, Geoffrey Rush, Louis C.K., Matt Lauer, documentarian Morgan Spurlock, Pixar Animation head John Lasseter, Girls writer and producer Murray Miller, Jeffrey Tambor, Tom Sizemore, One Tree Hill showrunner Mark Schwahn, George Takei, Gary Goddard, Steven Seagal, Warner Bros. producer Andrew Kreisberg, talent manager Benny Medina, agent Adam Venit, Richard Dreyfuss, Jeremy Piven, Matthew Weiner, Amazon executive Roy Price, Robert Knepper, Ed Westwick, T.J. Miller, director Brett Ratner, and Danny Masterson.

Weinstein is just the most egregious manifestation of an industry-wide tolerance of abuse. Of course, not everyone knew about every alleged instance. Some in power were insulated from it; others appeared to willfully look the other way. Increasingly, a larger, more devastating scandal took shape: It wasn’t just that the people around these men had permitted this kind behavior. Instead, the unfolding scandal illuminated how effectively the industry had convinced itself, its audience, and the press tasked with covering it that this sort of behavior was a thing of the past.

Each new wrinkle in Weinstein’s abuse of power — accounts of how he forced Salma Hayek to perform a lesbian sex scene to placate his dissatisfaction with Frida, or how he blackballed Mira Sorvino and Ashley Judd at pivotal points in their careers — is devastating. But they also point, again and again, to a larger, even more unsettling revelation: This was Hollywood all along.

So what changed? What moved the boundaries of scandalous behavior? The obvious answer is Donald Trump, and the failure of allegations of abusive behavior to become scandalous enough to exclude him from the presidency. But there’s also significant precedent in American history for such a sudden and seemingly consequential shift in public perception: two scandals, now nearly a century old, but both so embarrassing, so damaging, that they forced their respective industries to install self-regulatory agencies. These agencies were intended to “cleanse” their industries of immorality and corruption, but their primary purpose — in Hollywood in particular — was to reinstate the sort of mythology that would, decades later, protect Weinstein and dozens of other abusers.

The first of these scandals involved baseball’s so-called Black Sox, in which eight members of the White Sox accepted bribes to deliberately lose the 1919 World Series, and resulted in their lifelong ban in 1920. Second: Fatty Arbuckle’s 1922 arrest, and three subsequent trials, for the manslaughter of a young woman who died of a ruptured bladder after entering a bedroom with Arbuckle at a party at the St. Regis Hotel in San Francisco. The woman’s condition was never connected to any actions on Arbuckle’s part, yet Arbuckle, at that point the biggest star in Hollywood, was blackballed for the rest of his career.

As cultural historian Sam Stoloff argues, the purported actions of Arbuckle and the admitted actions of the White Sox took on such scandalous significance because of anxieties they seemed to confirm: that industries, founded by or “infiltrated” by Jews, were subject to deep corruption; that the new-found American idols of sport and cinema were men of weak character, in part because they did no “actual” labor; that sudden stardom, and the skyrocketing salaries that accompanied it, led to perversion; and that Hollywood was, indeed, the den of iniquity claimed by reformers from the start.

Such attitudes were amplified and exacerbated by the press, but as Stoloff points out, they also served as a natural culmination of anxieties about what it meant to be an American, festering since the end of the Great War. Most of these anxieties stemmed directly from the continued spread of what we now call “modernity”: the rise of the automobile, the motion picture, and an increasingly automated workforce, but also larger social shifts, including the black migration to the Midwest and East, the entrance of women in the public sphere, the continued effects of immigration, the devaluation of “traditional” labor, and the spread of communist thought.

A moment, in other words, not dissimilar from today, but made all the more ideologically frantic by the fact that the prophesized ruin that would supposedly follow all of those developments, whether actual or moral or financial apocalypse, had not come to pass. People were prospering, in many ways, and — especially for women and people who weren’t white — like never before. But that prosperity, along with other changes, threatened the myth of American identity, upheld by the solidly white middle class. Hence: the uptick in KKK activity and lynching. The “Red Scare,” which aimed to root out communist “infiltration” of American institutions. Rampant, unabashed anti-Semitism. Anti-immigration sentiment. Moral panic over women’s sex lives. And Conservative rule. Again, not dissimilar from what’s happening today.

Stoloff suggests these reactionary policies and postures are manifestations of what Richard Hofstadter famously called “The Paranoid Style in American Politics”: the American tendency, following a great crisis or upheaval, to “see the presence of a vast invisible conspiracy that threatens the total destruction of the established order.”

Few things crystallized the 1920s’ anxieties quite as powerfully as the reporting on, reaction to, and aftermath of the Black Sox and Fatty Arbuckle scandals, which ultimately led to the self-regulation of both businesses (so as to prevent governmental oversight) and assurances of overarching reform. This reform was to be administered by the moralizing arm of the newly appointed baseball commissioner (who banned all eight players, despite their acquittal in court on charges of “conspiracy to defraud”) and the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA), which promised to govern both the content of films (via the soon-to-be-developed Hays Code) and the behavior of the stars who appeared in them.

Crucially, both professional baseball and Hollywood were in their infancy; it was easy to argue that oversight and self-regulation, once installed, would fix the larger problems (of stars running wild with power, in particular) that both scandals revealed. But regulation did not, in fact, fix those problems. Instead, through spin work and studio-employed “fixers,” they prevented the problem of public knowledge of those activities — which allowed the public to reinvest in the myths (of American identity, of proper masculinity and femininity, of Protestant work ethic and self-denial) that the scandals had brought into question.

Which is why, until now, no scandal had rocked Hollywood — or shattered audience confidence — in quite the same way. Not because of the stars involved or the industry itself, but because Hollywood’s publicity apparatus became far more skilled at spinning it or covering it up entirely.

Two years after the Arbuckle scandal, Wallace Reid — a sort of Chris Hemsworth meets Chris Pine meets Chris Evans of the Silent Era — died from complications from heroin withdrawal. The head of the MPPDA collaborated with Reid’s widow to frame his death as the result of an addiction to painkillers, which he’d supposedly taken so that he could keep making films for his worthy fans after sustaining an injury while filming a stunt. Together, they produced an after school special–like film, embarked on a national anti-drug crusade, and planted dozens of articles in the fan magazines, effectively painting Reid as a tragic victim.

The plan worked, and the vision of Hollywood as a place of no tolerance for illicit, immoral, or otherwise un-American behavior remained intact. If and when a star’s behavior threw that image into question — whether it was Clara Bow, Rudolph Valentino, Jean Harlow, or Paul Robeson — their actions were covered up until they couldn’t be covered anymore, at which point the stars became sacrificial lambs, like Arbuckle: expelled, shunned, or otherwise blackballed in service of the greater myth.

It was understood that men controlled the entertainment industry. At the time, it was understood that men controlled every industry. It was also understood, if unspoken, that abuse, harassment, or unwanted advances were an accepted cost of a woman “making it” in the business. If she was raped, it was because she slept around; if she found herself on the casting couch, she was a no-talent slut; if she was date-raped, it was because she had been flirting on set and asking for it.

The female film stars of silent and classic Hollywood were some of the most powerful and respected women in the world, but they were never free. If they reported abuse of any kind, it would be used against them as evidence of their unruliness, of nymphomania, of uppityness. Their actions, rather than their abuse or abusers, would become the source of scandal — an attitude that persisted, more or less unchanged, for the better part of the next century.

When the controls of the studio and star system began to disintegrate in the 1950s, the immediate scandals — Ingrid Bergman’s affair and child out of wedlock, Robert Mitchum’s marijuana arrest — largely served as teachable moments for the rest of the industry, which quickly learned how to spin or blunt the actions of the newly “freed” stars. Mitchum, who had been jailed, did a mini reform tour, posing for fan magazine pictures with his son. Bergman disappeared from Hollywood after her scandal, but when Rita Hayworth began a potentially scandalous affair with a “Moslem Prince,” the press spun it as a fairytale. The “scandal” of Marilyn Monroe’s overt sexuality was cloaked by tales of domestic devotion — to men who, as later became clear, psychologically abused her. Agent Henry Willson protected his stable of male actors, many of whom were gay, by creating hyper-masculine, hyper-American identities for them — and by exploiting their dreams of stardom for personal sexual favors. The list could unspool forever.

Hollywood was built on a straightforward, accepted dynamic: Men control, men make more, men are subjects of their own narratives; women are controlled, women make less, women are objects within men’s narratives. Part of this dynamic was an unwavering belief that, despite any signs to the contrary, Hollywood was a fundamentally moral place, filled with good people whose only and abiding desire was to entertain the masses. There was nothing dirty, or corrupt, or secret about the way things were done — and suggestions otherwise, as published in magazines like Confidential, were un-American smear jobs. If you read them, or believed them, you too were un-American, or at the very least prone to prurient thoughts.

The days of fixers and fan mag–arranged marriages were over. This was the new Hollywood, not a curated vision of it.

But at the same time that Hollywood was insisting on its own moral rectitude, it was also gradually expanding the parameters of “moral” behavior — a process facilitated, and even necessitated, by America’s own shifting mores. From the ’60s onward, it became increasingly common for stars to admit to drug use, for female stars to talk frankly about sexuality, for divorce to proceed without the once-requisite moral gymnastics. But Midnight Cowboy’s 1970 win for Best Picture and the success of films like The Graduate and Klute simply created a new, but equally hollow, myth — this time of Hollywood’s forward progress.

Throughout the 1950s and early ’60s, there was still real tension between conservative forces within the industry, including gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, many of the fan magazines, and several major stars, who were inclined to preserve the image of Hollywood as a wholesome power for good, American fun. But as more and more stars declined to outwardly abide by Hollywood’s morality code, the real shift wasn’t toward “immorality” so much as self-righteousness: You could try to stifle Hollywood, this new narrative suggested, but it would always resist, and never again allow its true self to be censored. The days of fixers and fan mag–arranged marriages were over. This was the new Hollywood, not a curated vision of it.

In the years to come, Hollywood would be celebrated — and celebrate itself, via awards — for its frank depiction of the Vietnam War, for its political activism, especially on the part of its male liberal stars, for its incisive satire (M*A*S*H, Shampoo), and its interrogation of racism (Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner) and labor issues (Norma Rae). It was a place where “art,” embodied in the form of “silver age” geniuses like Coppola, Scorsese, and Spielberg, flourished amid commerce. The stars eschewed the fan mags, talked shit about “press agents,” and sat for revealing interviews with the journalists of the “new journalism.”

This new vision of Hollywood was the one that venerated Sidney Poitier, wore red ribbons for AIDS awareness, openly mourned Rock Hudson. It was more open, less judgmental, and more progressive than Old Hollywood and its studio system, which, through dozens of widely consumed memoirs, tell-alls, and films, had become known as a deeply repressive and dark place, antagonistic to art and real talent. Old Hollywood might have been a horrible place for women and people of color and gay people, but this new Hollywood was a place where independent art cinema flourished, where a woman could be nominated for Best Director, where a film like The Crying Game could become the most talked about of the year.

But this understanding of Hollywood — as progressive, tolerant, multicultural, and unoppressive — was just as superficial as the myth of a moral Hollywood. Films celebrated for their noble treatment of other cultures were, at heart, white savior narratives; when nonwhite people were nominated for awards, it was almost always in roles that facilitated the moral development of the leading male character. The vast majority of directors and producers were still white and male. People magazine was no less curated than Photoplay. The gay narratives that made it onscreen were all sanitized; at the same time, gayness was sufficiently stigmatized within the industry that in 2003 Tom Cruise sued for libel, and won, when a porn star claimed he was gay. Cruise’s legal team successfully argued that suggestions of homosexuality would demonstrably alter his star value.

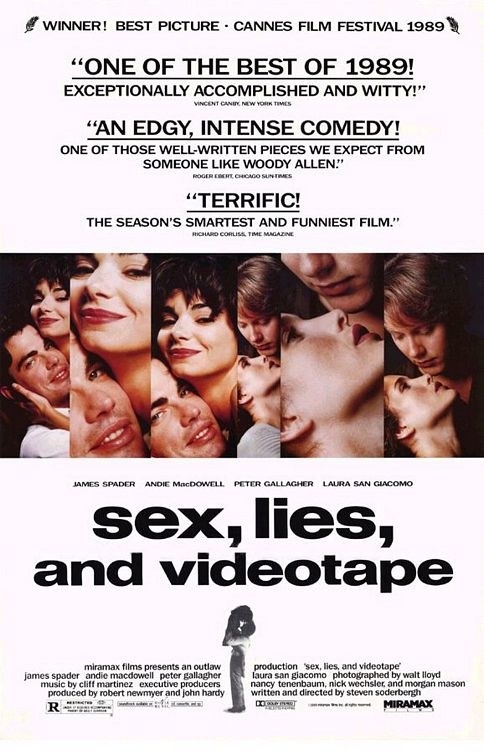

Few people contributed to a mythic, progressive vision of Hollywood in the 1990s and 2000s as much as Harvey Weinstein. Working with his brother, Bob — who produced the low-brow genre films that funded the high-brow prestige ones — Harvey’s success, and the films and stars and directors that paved the way for it, became proof of a new market and appreciation within the industry, where arthouse and “controversial” and foreign language films could thrive. This idea was especially appealing after the 1980s, when continued conglomeration and blockbusterization — along with the continued spread of cable — had dampened whatever creative spark remained from the auteur-driven ’70s.

Independent cinema, especially Weinstein-produced and/or -distributed films like Sex, Lies, and Videotape, Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, The Crying Game, Pulp Fiction, Kids, Il Postino, and The Piano, became proof of Hollywood’s expansive, liberal, creative capacity. Of course, that was all marketing — brilliant marketing on the part of Weinstein, who has never had a taste in cinema so much as a keen eye for publicity. He “loved” cinema inasmuch as he loved winning awards and making massive profits off films that had been produced cheaply, purchased, and made to appeal to larger audiences. He didn’t celebrate a female director like Jane Campion so much as he recognized the marketing value in the narrative of the first female director nominated for an Academy Award. Whatever was novel or experimental, beautiful or different — queer love stories, feminist films, foreign imports — was valuable to Weinstein only to the extent that it could be used as a tool, a slogan, an argument for prestige.

Hollywood loved what the success of Weinstein’s films, and the attendant rise of Sundance and indie film culture, suggested about the industry as a whole. Other studios attempted and ultimately failed to emulate his success, creating “indie production” units that — like much of Weinstein’s own productions in the 21st century — failed to make enough, or win enough awards, to justify their cost. The kinds of storytelling associated with Weinstein-era “indie” filmmaking have largely moved to straight-to-VOD or prestige television.

Even before Weinstein’s actions became public knowledge, Hollywood could no longer frame itself as a place where creativity or experimentation is nurtured, or where perspectives other than those squarely aimed at the great middle of the global audience could be celebrated. In truth, it never truly could. Weinstein’s success simply allowed the industry and its audience to believe otherwise.

Weinstein’s reign ran parallel to the development of a seemingly disparate, but no less significant, Hollywood myth: that of the transparent star. Old-school stars were bigger and grander, this understanding went, but they were also the creation of massive studio publicity teams. Proof was in later revelations surrounding the “real” humans behind the star images: Rock Hudson wasn’t even straight; maybe Cary Grant wasn’t either; Joan Crawford was a bad mother; Grace Kelly got around. The machinations surrounding the stars of the 1980s, especially ones as massive as Tom Cruise, were no less intricate or manipulative, but they were more effective in erasing any evidence of a PR campaign.

In the early 2000s, the rise of Us Weekly, whose “Stars: They’re Just Like Us!” humanized celebrities while fostering a market for paparazzi shots of “everyday life,” reinforced this myth. So did the subsequent rise of digital photography, “citizen” paparazzi, streaming video, and independent gossip blogs (Perez Hilton, Lainey Gossip, Dlisted, Oh No They Didn’t) that published them.

At first, these tabloid developments proffered revelations — and mini scandals — of their own: that Tom Cruise was an asshole and a dork; that Britney Spears was mentally unstable. The traditional publicity powers (People, Entertainment Tonight, E!), with their meager online arms, were powerless to counter this new gossip industry. For this brief period in the mid-2000s, the narratives of who the stars were and what they represented was wrested from the powers that be.

Yet the temporary rupture in the publicity apparatus was repaired, swiftly and with little fanfare, as the stars took back their own narratives in more recent years — not by relying on People magazine, but by embracing social media, which permitted a direct line of communication to their fans and created a gloss of unfiltered, uncensored access to the “real” star. Not all stars adopted these forms; in fact, many of the largest, most established stars refused them altogether. Yet with the encroachment of Instagram, Vine, and YouTube “stars,” social media became indispensable, even essential, for the new class of Hollywood.

As jaded and skeptical as audiences are now considered to be, we remain susceptible to this foundational myth of Hollywood: that the stars are who they say they are. Social media, with its aura of unmediated authenticity, has revivified that myth — even, importantly, for the stars who don’t use social media — in the 21st century.

Enter 2017, and the great “revelation” of Weinstein’s behavior. “Revelation” is in quotes because, as so many have attested since, his behavior was a widely known and badly kept secret within the industry. It was the subject of numerous gossip blind items and uncomfortable jokes; it was explained or understood as “Harvey being Harvey,” and was only rendered incendiary when exposed to the oxygen of public knowledge. Weinstein’s behavior itself wasn’t scandalous to Hollywood. Rather, public knowledge of his behavior — the extent of it, the complicity in it — rendered it scandalous.

Weinstein’s behavior itself wasn’t scandalous to Hollywood. Public knowledge of his behavior — the extent of it, the complicity in it — rendered it scandalous.

As with the Black Sox and Fatty Arbuckle scandals almost a century before, Weinstein’s actions became industry-threatening because of their placement amid — and encapsulation of — a slew of era-defining current events. Weinstein, after all, is far from the first major figure to be accused of sexual misconduct in recent years: Bill Cosby, Roger Ailes, and Bill O’Reilly were all stripped of power and contracts. But the reaction to the Weinstein allegations cannot be separated from the lack of enduring reaction to allegations against (and audio recordings of) President Trump. In many ways, the strength of the response to Weinstein — and the fortitude and continued fallout of the #MeToo movement — is a direct result of the weak response to the allegations of misconduct linked to the president.

But even that’s too simple. Our current moment of reckoning cannot be disentangled from the enduring gap between the promises supposedly fulfilled by second-wave feminism (increased freedom, choice, and power) and the reality of what it’s yielded (abiding fear of sexual assault and harassment, increased legislation of reproductive freedoms, the enduring wage gap, the uncrackable glass ceiling, and the absence of programs, such as paid maternity leave or child care, that would lead to actual change). Regardless of one’s personal feelings about Hillary Clinton, our treatment of her — from the right and from the left, from public officials and private citizens — evidenced just how effectively misogyny and sexism have been normalized, even in an era in which many believe feminism is no longer necessary.

The response to Weinstein, and the tidal wave of #MeToo accounts that followed, was fueled by this frustration, which had been building with each suspended sentence for a college rapist, each bungled apology and excuse, each report of the systemic ways in which women remain underpaid and underappreciated in industries, including Hollywood, built on the backs of their labor. The subsequent, detailed revelations about how Weinstein’s reported harassment — or his targets’ refusal to abide it — damaged various women’s careers have only further amplified this frustration. It’s not just about the acts of sexual assault and harassment, which are egregious enough. It’s about how assault and harassment, and the power dynamics they hinge on, sustain both patriarchal control and the continued (financial, physical, emotional) subjugation of women in general.

What makes the revelations of the #MeToo movement so “scandalous,” then, is the extent to which society at large and Hollywood in particular had previously bought into the idea of itself as a place where this sort of behavior was no longer accepted: where men are woke, or are, at the very least, not dicks with buttons under their desks to lock their doors; where sexual assault is rare, reported, and punished; where women can have any job they put their minds to; where women in power are celebrated instead of masculinized, desexualized, and viewed as threats; where women don’t willfully collaborate in covering up the mistreatment of other women; where the success of Wonder Woman means Hollywood will consider the roles and directoral chances it offers women; where no one is in the closet; where every star’s true self is laid bare in every interview, every Instagram, every statement screenshot from the Notes app and posted on Twitter. But that was never actually the world we were living in.

Alongside the supportive reaction to the #MeToo movement, an equally potent wave of paranoia has emerged, with some fearful that women will take the moment too far, that men will no longer be able to hug women, that accusers (specifically those of Republican candidates) were funded by conspirators (George Soros, the so-called “Deep State”). Some of this paranoia is a subset of generalized Obama-inspired, Trump-ratified birther shit. But some comes from men like Matt Damon voicing their anxiety that a pat on the butt has become indistinguishable from rape or child molestation, or New Yorker cultural critic Masha Gessen arguing that a watershed moment is in danger of becoming a “sex panic.”

When it came to Arbuckle and the Black Sox, the paranoia that exacerbated those scandals concerned the larger misdeeds of the industries that sheltered the men involved. This time, the paranoia centers on the agents who illuminated the scandals themselves — women — and how their revelations might change the way men have become accustomed to behaving in the workplace. Even if George Soros is the most commonly named architect behind some larger conspiracy, make no mistake: It’s a fear of these women taking action, rather than the actions of the men they’ve accused, that has prompted the most paranoiac attempts to discredit their message.

Left to fester, a scandal might actually infect and destroy the foundation of what it exposed. Which is why efforts to contain them are so swift: Weinstein and others accused of misdeeds become the sacrificial lambs, rightfully expelled in order to protect the greater whole. But the system, once patched, simply begins to reproduce itself. Ousted male executives are replaced by other male executives. An industry-appointed committee, not unlike the MPPDA put in place by the studios following the Arbuckle Scandal, makes a high-profile appointment (then, well-known social crusader Will Hays; now, Anita Hill) whose primary purpose is the appearance of serious self-regulation against future abuse.

The refusal to name patriarchal control as the ultimate source of this scandal means the lie will simply rebuild itself.

In the 1920s, Hays’ primary objective was to root out and cover up what was then considered and called “immorality.” Today, Hill’s mandate — and Hollywood’s at large — will be to defend against our new definition of “immoral” acts. But the acts aren’t the underlying problem. The real problem is the deeply inequitable system, one essentially built to produce them.

The refusal to name or truly address patriarchal control as the ultimate source of this scandal means the lie will simply rebuild itself, cloak itself in the auspices of truth, and sell itself as progress until the next revelation threatens to combust the system — at which point it, too, can be contained, and the system can carry on.

The best definition I’ve heard of “ally” is of someone willing to give up elements of their power or privilege in order to allow the person with whom they’ve allied themself to enjoy that power as well: to truly and demonstrably even the playing field. If Hollywood truly wishes to prevent another Weinstein-like scandal, it will have to stop thinking in terms of committees and apologies, and start thinking in terms of actual, system-altering, paradigm-shifting, non-performative allyhood.

Not because it looks good for social media, or because stars can wear a ribbon to celebrate it at the Oscars, but because of the radical belief that the sort of power imbalance sustained by Hollywood will not only produce victims, but hide them, at any cost necessary, in order to sustain itself. ●