“We’re like a cult,” a tan, freckled, ambiguously aged woman tells me, the dregs of Coors Light swishing in the bottom of her plastic cup.

We’re in the women’s bathroom of the Ballard Elks Club, decorated with white wicker furniture and a tray of drugstore lotions and hairspray. “The guy I’m seeing, he’s a member too,” she continues, stuffing her phone into her Louis Vuitton purse. “And we’re trying to convince the club to do a fundraiser so we can go around and do to other clubs what we’ve done here.” Specifically: Make the Elks more appealing, more vital, maybe even cool — while still preserving its ties to both its old Seattle neighborhood and the longtime members who remain its core.

The woman is wearing an oversized faux fur vest and heeled suede boots, which is to say she’s dressed for neither the Elks nor Seattle. But the mother of two is a regular fixture at the lodge, which she joined about four years ago, so that “my kids would have somewhere to pee when we were at the beach.” That beach, right on the Puget Sound — and the bar that extends above it — is how the vast majority of the new members at the Ballard Elks found out about the lodge, which is one of the fastest-growing in America, mushrooming from around 800 members in 2012 to over 1,200 today. The lodge’s median age, 52, is the lowest in the country — and a figure that, if current trends hold, will only continue to fall.

Fraternal organizations have always met specific cultural needs. In Ballard, the Elks are a salve for very contemporary syndromes.

Many Ballard Elks were first drawn to the beach parking and cheap drinks, but have found that their investment in the lodge, and the community that forms around it, has transformed into something more. Fraternal organizations have always met specific cultural needs — providing a space for men as women entered the public sphere at the turn of the 19th century, and a return to the brotherhood of military service after both world wars. In Ballard, the Elks are a salve for very contemporary and Seattle-specific syndromes: For transplants, it’s an antidote to the “Seattle Freeze,” the term for the difficulty non-natives face in making friends or finding dates; for natives, it’s a retreat from the Amazon-incited condo-ization of the city as a whole and Ballard in particular.

But it’s also part of a national phenomenon: For the first time in 35 years, the Elks are growing. Average member age is down from 69 to 61. Membership is exploding in San Francisco, the Florida Keys, North Carolina, and dozens of other areas, including the bedroom communities of New Jersey, where Eli Manning was just voted to membership. Each of those lodges has a story of where that growth is coming from, yet the impulse remains constant: seeking connections, with people who are not necessarily like them, in dusty old buildings with $2 drafts and animal heads hanging over the doorway.

“I tell people that I’m part of the Elks and they give me funny looks,” Ben Braden, who sits on the Ballard Elks’ executive committee, told me. “But then I take people here and they’re like, ‘Do I have one of these in my neighborhood?’”

The Elks and similar fraternal organizations were part of a broad trend of “joining” and civic engagement that started in the 1880s, dropped off during the Great Depression, and surged following World War II. “Fraternal organizations,” writes historian Robert D. Putnam, “represented a reaction against the individualism and anomie of this era of rapid social change, asylum from a disordered and uncertain world.” Many provided “material benefits” like life and health insurance, as well as “social solidarity and ritual”; by 1910, more than one-third of adult males over the age of 19 were a member of at least one.

Some, like the Jaycees, the Rotary Club, the Kiwanis, and the Lions, were more explicitly business-oriented; others, like the Odd Fellows, were more invested in providing care for their members; while the Black Elks, Black Moose, and dozens of others developed similarly robust organizations segregated from their white counterparts. The Elks were officially desegregated in 1973, but black members were routinely denied membership through the 1980s. Today, most lodges have diversified: While many, especially in rural areas, remain largely white, there are dozens of clubs whose membership is almost entirely black; in Charlottesville, Virginia, the Elks Club has become “the only real place for black folks to go.”

As late as the 1970s, the lodge was where you went to dance on a Saturday night, to dress up on New Year’s, to play bridge and hobnob and drink under the auspices of charity. Franklin D. Roosevelt was an Elk; so were Truman and MacArthur and Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy.

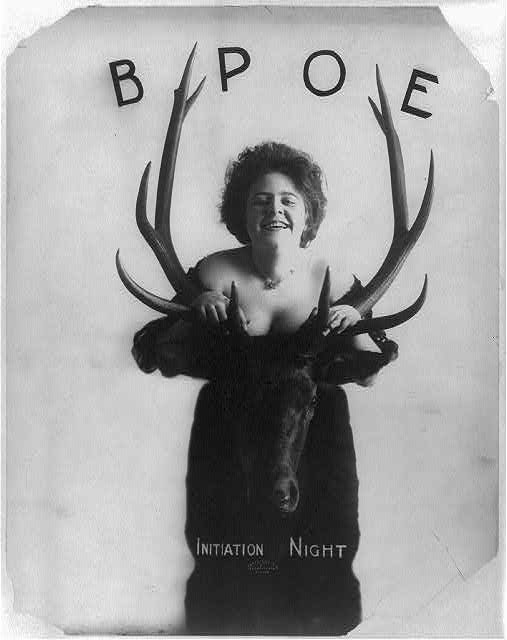

The Elks — officially known as the Benevolent and Protective Order of the Elks, the BPOE, or, if you ask an Elk who likes dad jokes, “the Best People on Earth” — was founded in New York City in 1868. The specific lore of the early Elks has filled books, but the bare facts, as presented during a recent Ballard new member orientation, are easier: “Some actors wanted to drink on Sundays, which wasn’t allowed at the time, so they put together a private club so they could succeed at that. Gradually that group started doing more with charity, and a lot more with veterans, but it was pretty much a men’s organization.”

The group voted to name itself the Elks, narrowly defeating the Buffaloes, and borrowed much of its ritual from the Freemasons, then one of the largest organizations in the country. By 1910, Elks done away with almost all of the ritual — including secret handshakes and passwords — and settled into the function they held for much of the 20th century: a group of (white) men, initiated only upon recommendation from another member of the lodge, who paid yearly dues, enjoyed lavish facilities built with those dues, and donated time and money to local, state, and national charities.

Elks membership was fueled by a “long civic generation,” as Putnam calls it, born between 1910 and 1940, who were more engaged in community projects, more trusting of others, and far more likely to vote than their grandchildren are today. The Elks and other fraternal orders — along with bowling leagues, churches, women’s associations, and bridge clubs — offered a deep well of what sociologists call “social capital,” which, studies have shown, makes people feel more secure, less alone, and more, well, happy.

There are myriad reasons for the decay in social capital and civic investment: women moving full-time into the workforce, suburbanization and resultant commute time, television, globalization, changes in the family unit, and a general distrust and disillusion with politics and efficacy of civic engagement. The “ebbing of community,” Putnam writes, “has been silent and deceptive”; membership in nearly every civic activity, from the PTA to card games, has more than halved since the peak of involvement in the 1960s.

But few civic disengagements have been as visible as what’s happened with the Elks and organizations like it. Before World War II, membership was at 1.1 million and growing at a rate of 110,000 new members a year. In 1976, membership crested at 1.6 million, but over the next 30 years, as the “civic generation” began to die off and boomers and Gen X came of age, membership plummeted to 850,000. But 2016 marks a reversal of that trend.

All cities are a collection of neighborhoods, but Seattle’s location — hedged in and bisected by water — makes it more so than most. The city’s geography most resembles Manhattan: the urban core attenuated thin with Puget Sound on one side, massive Lake Washington (past which lies Microsoft and the ritzy, suburban Eastside) on the other. Instead of Central Park, there’s Lake Union, filled with floatplanes and houseboats. There’s Green Lake to the north and the polluted Duwamish River meandering south, and in between all that water, there are neighborhoods: the radical and queer of Capitol Hill, the chichi of Queen Anne and Magnolia, the hippies of Fremont, the pan-Asian enclave of the International District, the aspirational squares of Wallingford and Green Lake, the young families of West Seattle, the historic African-American community of the Central District, and the sleepy, Scandinavian-infused world of Ballard.

That is, until Amazon — and its estimated $5 billion citywide impact and 24,000 Washington employees — happened, and every neighborhood seemingly transformed into an amalgam of overpriced condos with “living roofs,” hot yoga studios, CrossFit boxes, bars with $7 microbrews on tap, and transplants willing to pay for all of it. The bad traffic got worse, the city grew even whiter, and it became impossible for most middle-class families to buy a home in the city. The dream of Seattle had been colonized by a bunch of rich dorks in performance gear who didn’t even know how to flirt.

Or so the narrative goes. In truth, Seattle’s transformation resembles that of San Francisco, Austin, and Brooklyn — and is a natural extension of gentrifying processes set in motion more than 20 years ago. While there are certainly real and distressing changes in the way that Seattleites actually live, one of the biggest changes is a state of mind: Seattle just feels different. There are plenty of Bernie Bros and kayakers to protest Shell Oil, but the things that made Seattle seem unique, its own particular sort of nerdy-nice grunge, seem to be in flux.

The dream of Seattle had been colonized by a bunch of rich dorks in performance gear who didn’t even know how to flirt.

Few Seattle neighborhoods have experienced that change in feel as acutely as Ballard, which, more than any other Seattle neighborhood, has always felt like its own tiny town, in part because it was — at least until the early 1900s, when it was annexed, under much protest, to the city of Seattle. Back then, Ballard overflowed with Scandinavians, Norwegians in particular; according to lore, local law required a church for every bar, which resulted in a profusion of both.

Ballard was isolated, both demographically and physically, from the rest of Seattle; today, locals like to say it’s “20 minutes from everything.” One hundred years ago, most of the people who lived in Ballard worked in Ballard, whether in the marine industry, the shingle mills, or the tidy spread of shops, banks, bookstores, and restaurants that lined Market Street.

The community was bound by its common culture — a Nordic Heritage Museum, a yearly parade celebrating Norwegian independence, lefse at the local grocery store, and dozens of middle- and working-class fraternal organizations: the Sons and Daughters of Norway, a robust VFW, and outposts of the Eagles, the Odd Fellows, the Moose, and the Elks, who owned an ornate building in the center of Ballard before moving to their current location, right in the elbow of Shilshole Bay.

The route to the Elks is choked with new condo developments, their siding painted tasteful, bold colors (turquoise, mustard yellow, brick red) and lined in white trim. They all rent for about $1,500 to $3,000 and boast views of water and walking distance to Ballard Avenue, a bricked street lined with gastropubs, French brasseries, shops that sell cute sandals and even cuter baby clothes, and bars with names like Shelter and King’s Hardware that literally overflow with twentysomethings.

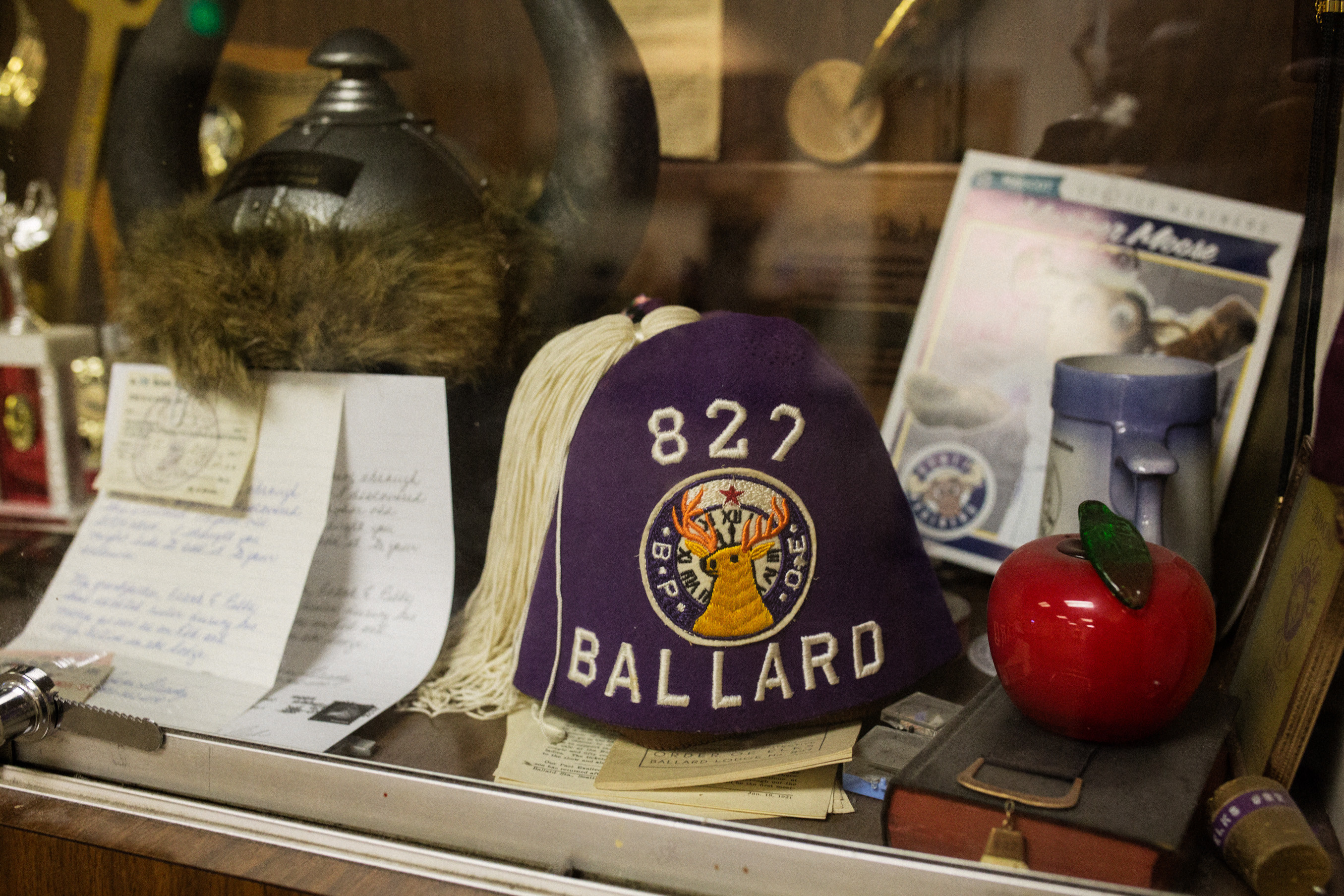

The sign for the Elks bears the distinctive Elks “E”: a backwards 3 that looks like it’s been scribbled in thick marker. Anyone who’s lived long in Ballard has attended a memorial, a wedding, or a party in the ground-floor ballroom, the rental of which is contracted to an outside catering company. But the upstairs is Elks territory, in all its wood-paneled glory. There’s the event space — panoramic windows, a mounted elk head, and ample space for the line dancing, Zumba, and waltzing classes — and the “social quarters,” resplendent in old photos, vinyl bar chairs, a shuffleboard table, and a digital jukebox (one night, it played Fine Young Cannibals’ “She Drives Me Crazy” on repeat).

At the bar, there’s a cluster of hunched old-timers, a baseball game on the television, and the rhythmic movements of the bartenders — blonde, slightly weathered, and unrivaled when it comes to remembering both your name and drink. But on a clear day, the real action’s outside on the deck — which is where a kayak fisherman named Brad Hole is waiting for me.

Seattle weather is the only thing about the city that’s temperamental or contrary. When it hit 80 degrees late this past April, the city filled with Velcroed sandals, summer skirts, pale legs, and musty athletic gear — all of which could be found in abundance at the Ballard Elks at 5 p.m., where Brad was prepping to brief the latest crop of initiates. This month the number’s around 30; usually it hovers between there and 50.

Brad Hole is prototypical Ballard Elk: Years ago, he started using the beach as a kayak launch and joined the lodge after a friend invited him up to the bar. Today, he’s wearing a purple Hawaiian shirt emblazoned with the Elks symbol from the club in Honolulu. “I got it off eBay,” he explains to everyone who asks. “You wouldn’t believe the old Elks stuff on there.”

Brad has a jolly build and a salt-and-pepper beard; he’s somewhere in his forties, drinks Coronas, and has lived in “Old Ballard,” as people call it, “forever.” Along with his girlfriend, Anne, he functions as the club’s de facto welcoming committee, responding swiftly to emails, talking up the club, and ushering new members through initiation.

He folds and unfolds a scrap of paper where he’s doodled the major themes of orientation: Here’s what you pay in dues ($99, paid every April), here’s the good we do (thousands of dollars every year to various charities), here’s your commitment (“The Elks is whatever you make it”). All members are required to check off boxes on an application stating that they believe in a higher power and to pledge that they have never attempted to overthrow the government — a recent modification from the stipulation that members could not be Communists.

All members are required to state that they believe in a higher power and to pledge that they have never attempted to overthrow the government.

Today’s group includes a broad-smiling, Anthropologie-vibed woman, in her mid-thirties, who became involved through the “Eat Ballard” neighborhood association; a couple with relaxed faces in their sixties who live in the condos next door; a real estate agent in her forties who “thought it’d be a good time to be part of a service organization”; and a youngish dad who runs a business refurbishing vintage furniture from his home, “just a pinecone’s throw away from here.” There’s also a pair of grizzly-bearded, round-bellied twentysomethings, one of whom just moved from Pennsylvania, where his grandfather’s an Elk. “I heard about the club through Rob Casey, because he surfs my tugboat wake.”

Surfs, as in rides a stand-up paddleboard behind the tug when it makes its way through the bay outside the club. Casey, who has the freckles and eye crinkles of someone who lives on the water, was one of the first to start stand-up paddling in Seattle. He’s watched as the sport, and the popularity of the beach next to the Elks, has exploded; over the last five years, he’s taught hundreds to paddle and introduced dozens to the lodge. Casey also arranges a weekly race — with a $5 entry fee — that attracts fiercely competitive paddlers, with all proceeds directed to the Elks scholarship fund. As the new members introduced themselves, a group of 20-plus Elks paddleboarders were grouped around a large table in the other room, putting the final touches on a plan that will allow them to store their boards in the lodge’s basement.

After introductions, Brad tells the initiates about the Facebook page, and the newly designed Elks app, and all the ways they can get involved: “What we’re looking for in a member is about five volunteer hours a month”; “You’re not required to go to meetings, but you get so much more if you do”; “You get a membership card, and with that card you can visit other lodges. We call it ‘going Elk’n.’” “It’s fun to get your friends to join, and to meet new friends here,” he adds. “It’s kinda like your own country club.”

“I like to remind people that once you’re an Elk, you’re an Elk for life."

At this point, Brad’s wingman, Scott — Tom Cruise–like head of hair; works in IT at the University of Washington — interjects: “I like to remind people, though, that once you’re an Elk, you’re an Elk for life. We expect those dues every year, unless you’re under duress. It’s a fun place, and a light place, but I wouldn’t take it lightly. The charity that we do here is pretty impressive. And it really makes you proud to be part of it once you see it happening.”

That philanthropy takes many forms, but unlike other organizations, the vast majority of it takes place on the local level. In the last year alone, the Ballard Elks have donated $9,000 in scholarship funds to high school students at Ballard High; a massive clothing swap brought in $2,000 and pounds of clothing for Mary’s Place, a resource center for homeless women and children. Nationally, the Elks raised $343 million in charitable gifts in 2015, and while each lodge pays dues on the national level, most funds remain local. “With the Elks, it’s all about transparency,” Rick Gathen, a representative from Elks National, told me. “With other organizations, a lot of dollars go to jets and national salaries; with us, people know where the money’s going. It directly impacts their communities, and they can feel and touch it.”

Millennials are philanthropic — 84% made a charitable donation in 2014 — but that giving is largely directed toward national, non-chaptered organizations; 62% of donations took place via an app, an email, or a text message, with little in terms of direct, visible results. But when that money stays local — when you meet the students who receive the scholarship when they come to the lodge, or watch the Girl Scouts run around the event space next door — it just feels different. It feels, as Putnam would put it, like social capital.

But why the Elks? Sure, the Freemasons are too mystical and readily associated with the villains of The Da Vinci Code; the Odd Fellows, whose membership once topped 2.7 million, can’t overcome their name; and the business networking function of the Jaycees, Lions, and Rotary have been overtaken by LinkedIn. Perhaps the growth stems from the fact that the Elks, like the Moose and the Eagles, have always been rooted in the social, the apolitical, the relatively low-commitment philanthropic. The Grand Exalted Ruler of an Elks lodge can hold office for only a single year; as a result, there are no ruling dynasties, and young and new members aren’t just encouraged to take control, but also essential to yearly operations. In many ways, the lodges are ciphers: event spaces malleable to the shifting civic and psychological needs of their members, instead of dictating them.

That malleability can also be disastrous, especially when new members don’t join the Elks so much as attempt to wholly make it in their image. In the early 2000s, the Elks lodge in Austin enjoyed a membership surge after a woman tried to sneak into the pool. A member discovered her, but, instead of kicking her out, brought her to the bar. Afterward, she brought her friends, and the lodge began to expand exponentially.

Those new members — composed of stockbrokers, tech workers, and other monied hipsters filling Austin in the mid-2000s — had a different idea of what the Elks could be: They wanted to eliminate the semi-alienating names for elected leaders, forbid smoking in the bar, and host functions like the one, in the mid-2000s, where Dead Kennedys singer Jello Biafra judged a bikini contest. Yet in 2011, the Grand Exalted Ruler was dismissed for “improper conduct,” which she alleged was part of a larger plot on the part of older, male members to remove her and other female leaders from power. Two years later, the Elks revoked Austin’s charter due to “lack of dedication, lack of interest, lack of knowledge of Annotated Statutes, and lack of respect for duly constituted authority.” Today, the once-new members have regrouped as The High Road, a nonprofit with a waiting list, access to the pool, and none of the hassle — or legacy — or an entrenched organization.

In Ballard, the age span is part of the lodge’s allure. Sometimes, there’s light friction — Lois Morgensen, the lodge’s secretary, finds herself annoyed with some of the aspects of growth (“All these people trying to get their spousal cards,” she told me, “and their last names are different!”). Old-timers who’ve been coming to the bar for decades feared that new events, like the monthly karaoke night, would make things too loud, too different. “But then they see what happens, and they say, ‘Wow, that was wonderful,’" Anne told me. "So we just have to keep showing them success.”

“I’m about as Seattle as you can get,” Ariel Nilsen tells me later that week between rolls of “the dice game,” a lodge tradition in which members pay a dollar for three rolls of the dice. If you get a Yahtzee, you win the accumulated pot and buy the rest of the bar drinks. “My family owns one of the shops on the lower level of Pike Place Market," she says, "and I spent my entire childhood running around there.” Like many Ballard Elks, she’s a “liveaboard” — as in, she and her boyfriend, who’s also an Elk, live on their boat, docked just down the road at Shilshole Marina. “I kept coming here with dudes, but finally I said, ‘You know what, screw the dudes, I’m gonna join. I don’t half-ass anything.’”

Which is why, within a month of initiating, Ariel found herself accepting a nomination to be a trustee. The position entails making critical decisions about the day-to-day operations of the lodge and the yearly budget — and, like the rest of the trustees and inner council, wearing a tuxedo to the monthly meetings. (“It’s so unflattering!”)

“You hear about the Seattle Freeze,” she says, “and it is alive and well. But this place bucks that trend. I’ve only been a member for three months, and I’ve met so many people. Dockmasters, fishermen, liveaboards, all of us odd ducks. But what I love about this place is you leave what you do at the door. People don’t come in to talk shop or rub elbows. And in a town where that’s no longer the case in a lot of ways, it feels really freeing.”

That’s precisely what drew Lauren Zuniga, a reedy 26-year-old who moved to Seattle from rural Kansas when her boyfriend got a job in tech. “I work from home in data entry and had a really hard time meeting people,” she told me on another 80-degree afternoon. “I was that freak talking to people at the gym and the grocery store, just trying to start conversation.” One day, she saw a flyer looking for Girl Scout leaders, and she was swiftly assigned to the brand-new troop that meets at the Elks. Within months, she’d joined the Elks as well.

Zuniga scrolls through photos on her phone, showing pictures of the girls, who span first through sixth grades, working diligently on various badge projects. “I asked the other leaders, do I need anything covered, like my tattoos or anything? And they said no way — just don’t cuss in front of the girls, and don’t drink before the meetings.”

One of those leaders, Liz King, pops into the bar and gives Zuniga a hug. She’s just there to pick up supplies for the massive lasagna dinner the troop’s hosting at the lodge that weekend (sold out at 200, raising $4,400 for the Scouts, 10% of which went to the Elks). “Making lasagna for 150 is totally normal for me,” she deadpans. “I’m Spanish and Italian; I have 38 first cousins — 200 will be nothing.” Zuniga asks King if she’s had the time to look at her résumé, which she’s promised to pass along to a colleague at the University of Washington. “I have some edits for you, — I’ll send you an email,” she replies, rushing out the door to make a literal mile of lasagna noodles from scratch.

The bartender pulls a bag of popcorn from the microwave and pours it into a bowl for everyone at the bar to share. “I just love Ballard,” Zuniga sighs. “I’ve only been yelled at to ‘go home, gentrifiers’ once! And here at the Elks, I don’t ever have to worry about my drink being spiked, or my purse being stolen, or guys harassing me.”

A man one seat down, silent our entire conversation, speaks up, his eyes still focused on the Mariners game in front of him: “And if you ever do have problems, you know, you can count on us.”

“If we were a mafia organization,” one member tells me, “then Lois would be the boss.” When I first meet her, she’s wearing a two-piece jean outfit with nautical embroidery and matching jewelry. She’s come out to the deck to remind Ben Braden that he’s got 10 minutes until the house council meeting. “Turning 90 again?” Ben teases. “No! 29 backwards!” she snaps back, an iron trap.

“Last year, we were going to do this party for her birthday,” he explains. “And she said, ‘I don’t want anyone to know it’s my birthday.’ So we put up these signs that said, ‘Celebrate Lois,’ and people came in and said, ‘Oh my god, did Lois pass away?’ But no, she was alive.”

“Very much so!” Lois interjects. “We had my party down here last Saturday night, and one of the gals, she had those things that you put on your titties and twirl around, and she glued them right on her sweatshirt!”

Lois has served as the secretary of the Ballard Elks “for more than 100 years,” managing membership rolls, dues, and correspondence. As recently as four years ago, announcements were made through a clipboard in the lobby; today, it’s all email and Facebook, both of which Lois has mastered. (“Let’s just say she knows how to use caps lock,” another member told me.)

In many ways, Lois is the go-to historian for the Elks: She’s been attending functions since the 1960s, when they were in their old building, and joined the Emblem Club, a still-vibrant auxiliary organization for spouses of Elks members that developed during World War I. Lois describes the lodge in the ’60s as “kind of weird.” “The women couldn’t come in the bar, which was up on the second floor,” she says. “'The stag bar,' they called it. Women weren’t even allowed to put a toe in that place.”

There are pictures of a younger Lois in the back of the club, the same firecracker look in her eye as she has today. “I didn’t join until the ’90s. I’d been widowed twice, but the gentleman I was going with at the time, he got me to join.” Women had been lobbying for entrance for years, but it wasn’t until 1996, when the Elks had already spent over $1.25 million litigating suits brought by women around the country, that the national organization voted to allow them entrance. Back then, a self-professed “old school” member of the Ballard Elks complained about the “eager-beaver” women agitating for membership: “When they’re twisting your arm,” he told the Seattle Times, “I’m sure it’s going to pass.”

Today, any hint of that resentment or reticence is gone — or at least undetectable — and the Elks has become Lois’s second home. Nearly every night, she drives the 10 minutes from her home in North Ballard and drinks MacNaughton and water out of a pink beer mug that everyone knows as hers. On her birthday, she received over 200 Facebook messages — the vast majority of which came from men and women at least a third of her age.

Portraits of officers of the Ballard Elks on the monthly initiation day. May 24, 2016.

Matt Lutton / Boreal Collective for BuzzFeed News

There’s a similar cult of personality around Nestor Tamayao, a retired Army communications officer who, along with his brother, Felix, joined the Elks in 2012. Today, Nestor, 65, serves as the Esteemed Loyal Knight, a sort of vice president to the club’s Grand Exalted Ruler. The brothers moved to the States in the 1950s when their father, who’d survived the Bataan Death March in the Philippines, chose to retire to Seattle after his own career in the military.

“So many changes since then,” Nestor told me over lunch at Ray’s Boathouse, the fancy seafood restaurant next door to the Elks, whose cocktails cost three times as much. “When my family lived in Wallingford, we were the only Asian family in the entire neighborhood.” Since then, the demographics of Seattle, like the Elks themselves, have been slow to shift. “You know, the Elks wasn’t open to people of color,” he tells me. “It wasn’t until the ’70s that they allowed male minorities to join. Today, there aren’t barriers like that.” As late as 1989, there was only one black member at the three Seattle lodges; today, lodges do not collect statistics about the racial makeup of their members, but a normal night more or less mirrors the makeup of Seattle: around 68% white, 14% Asian, 7% Latino or Hispanic, 8% black, and 3% biracial or other races.

Nestor and his wife moved to Ballard decades ago, buying a home that they’d never be able to afford today. He’s watched as the Ballard VFW, where he’s also a member, has declined — and fielded multiple all-cash offers for its slowly dilapidating building, situated in prime Old Ballard real estate.

It’s like home, in a time when that notion is very much in flux.

But he loves what’s happened at the Elks. “The youngsters, as I call them, they keep me young,” he says, his tone metered and deliberate. “They don’t look at me as some old fogy. One member couldn’t believe that I was older than his father.” He laughs, slaps the table. “I don’t want to sit in a rocking chair. This is a new chapter in my life.”

Organizations like the Elks span age groups, political orientations, sexual identities, classes, and, increasingly, race; in so doing, they foment “bridging” social capital — that is, connections with people who are not necessarily like you. In this way, the 21st-century version of the fraternal order — whose existence once hinged on insularity and exclusion — is making its members more empathetic. As multiple studies have shown, the more you drink and eat and do philanthropy work and live with people unlike you, the more likely you are to treat them as people, whether in your voting patterns, public speech, or willingness to help them in a time of crisis.

The renaissance of the Ballard Elks suggests, however quietly, that wide-scale civic engagement — and the bridging social capital and empathy that accompanies it — is returning. As Putnam argues, the history of civic engagement is not simply one of decline: “It’s a story,” he writes, “of collapse and of renewal.” The Elks, and organizations like them, are attractive not when they become “cool,” but when their absence starts to reveal itself as a lack — as something like sorrow. What the Elks provides varies from person to person, but the overarching gift remains the same: It’s like home, in a time when that notion is very much in flux.

“Go talk to that woman over there in the pink fleece,” Anne says, half under her breath. “She told me this day is a dream come true for her.” A week after new member orientation, it’s initiation night, and the steaks, served to every new member, are on the grill. The woman in the fleece just biked over from her job at the University of Washington, where she heads up Title IX compliance, specifically with sexual assault and violence. She grew up in Ohio; her grandfather was an Elk. “I believe in the Elks mission, and I believe in the community. So when I moved to Seattle, I asked myself, ‘How do I capture that same community?’”

“In my job, I’m in a world of ‘How do you make big global change,'” she continues. “Whereas here, it’s ‘How can I give to a food bank, or contribute a toiletry kit for the homeless.’ This feels like something I can wrap my arms around.”

Outside in the lobby, Lois and Brad are checking steak tickets. “We just got PayPal,” Brad announces, “so we’ve officially joined the ’90s!” He’s joking, but the adoption of digital technologies — like the ability to pay dues online instead of writing a check (which, until very recently, was the only way to keep your membership active), and an active Facebook page, and the app — has been crucial in expanding the Elks’ reach. The more robust the Facebook page, the rule seems to go, the healthier the IRL lodge.

The initiation dinner is a mix of new, recent, and longtime members, sitting eight to a table, with thin paper placemats emblazoned with a proud and fully racked elks. The steak’s especially good this week, according to Lois, because Felix is using a demi-glace. “I’m going back to the kitchen to get a piece of foil for my leftovers,” she tells me, “and I’m gonna tell Felix that was the worst damn steak.”

The head of scholarship, Karl Johan Uri, made a béarnaise sauce at home, and a small Tupperware of it is circulating at a corner table, where Ellen, in her early thirties, waits for her husband to arrive. “Isn’t this fun?” she asks no one in particular. “This is so fun.” Beside them, there’s a clean-cut guy in the Seattle-standard rolled-up Oxford who, after some questioning, admits he works for Amazon. “But I’m not a transplant!” he says. “I’ve been here 10 years!”

Across the table, John — somewhere in his forties, with a sprawling smile — brings up his initiation, back in 2012. “The guy who did the interview, Bronco, he told us, 'Do not join anything. Go to events, see what we do, and find one that appeals to you — or create one. We’re getting a lot of new blood, but we have to sustain it.’” John and his partner, Jake, chose bingo, helping run the Memorial Day events and eating monthly steak.

Jake has the round Norwegian face you see all over Ballard, and he first joined the Elks “a lifetime ago.” When he moved to Alaska, he became an “Elk in Bad Standing,” but when he started attending bingo with John, he paid a simple $25 fee and returned to the fold. The couple recently sold their sprawling home in the suburbs and downsized to a condo on the waterfront, where they walk to work and compete for the most steps on their Fitbits.

Before initiation starts and I’m ushered from the room, Jake asks, in a slightly tremulous voice, whether, during my two weeks with the Elks, I’d been able to stay past 11 p.m. “That’s when we remember all our forgotten brothers and sisters,” he said. “Any Elks club in the world, when the clock strikes 11, we recite the toast.”

The toast is ostensibly about the Elks, but it also ritualizes the broad and primal hunger to know that your presence has been, in some way, indelible — a dream that “joining,” and its attendant commitment, of labor, of capital, of care, guarantees. You can watch dozens of versions of it on YouTube, in various degrees of formality and intoxication, the words sticky in throats and scratchy on old gramophones. It’s been modified slightly over the years, but has remained substantively the same since the late 19th century, arriving, after a slightly weepy preamble, at its real heart:

“It is the golden hour of recollection, the homecoming of those who wander, the mystic roll call of those who will come no more. Living or dead, an Elk is never forgotten, never forsaken.” •

CORRECTION

Liz Mozzarella is the Girl Scout leader who picked up supplies for the lasagna dinner. An earlier version of this story misstated her last name.

The actors referred to in a quote regarding the origins of the Elks formed a private club after they wanted to drink on Sundays and it wasn't allowed. An earlier version of this story misstated that fact.

UPDATE

A name in this story has been changed to reflect the subject's preference.