“I’ll tell you why these neo-Nazis and fascists move here,” a man named Phil, who’d moved up to Glacier National Park after graduating from a liberal arts college, told me over dinner. “During the summer, I’d work at this place that rented all sorts of stuff to tourists in the park. So this woman comes in with a Southern accent, I ask where she’s from, she says Georgia. She rents one of those infant backpacks — the kind you put your kid in. And then she says, ‘This place is just so great — did you move here because there’s no black people?’

“I pause, look at her, and say, ‘Well, Kalispell has the most black people in Montana.’ This isn’t true, but I wanted to throw her. Then she says, ‘Well, what about Whitefish?’ And I say, ‘Well, it’s just all gay people.’ Again, not true. 'Columbia Falls?' she asks, and I say 'Filled with Hispanics.'"

“‘Well, we just want to get away from some of the, well, drama down there,’ this woman said, referring, you know, to Georgia.

“So she takes off with her husband and her baby, and I don’t see her again — until, months later, she comes back for a 9 mm unmarked pistol they’d forgotten in the little pouch on that infant backpack. ‘We moved here!’ she exclaimed. ‘We’re homeschooling our kids!’”

The woman in Phil’s story may not be a neo-Nazi, but she arrived in the Flathead Valley for the same reason that so many neo-Nazis, “Patriots,” and other fascists have: Flathead County, population 96,000, is one of the whitest places in the nation (95.2%).

There are other allures for people at odds with mainstream American culture: the large pockets of open space, the ability to live off the grid, the lack of restriction when it comes to gun ownership. The Montana political ethos — some mix of libertarian, conservative, and “don’t fuck with me” — is inviting that way. As a local pastor put it, “It’s a place where people can feel safe when they say outrageous things.”

The winters are frigid and last forever, but the summers are exquisite. Any direction you look, there are mountains. You can get a big house in the backwoods for under $100,000. For decades, tourists have come to town and asked shop owners the same thing: “How can I live here?” Starting in the early 2000s, white supremacists wanted in too.

Gradually, Montana became home to the highest concentration of hate groups in the nation. In the Flathead — which includes Kalispell (more industrial, more sprawling, population 22,000), Whitefish (a quaint grid of a resort town, population 7,000), and Columbia Falls (a former timber town, now filling with those priced out of Whitefish, population 5,000) — they mostly keep to themselves. Sometimes there’ll be a piece of Nazi propaganda slipped between pairs of expensive jeans in clothing boutiques; other times there’ll be flyers for “A Nature-Based, Race-Centered Religion for White People” folded in children’s books at the local bookstore. “Every place in town has a story like that,” one business owner told me.

But some things can’t be ignored. Like in 2010, when April Gaede — better known as the “Nazi stage mom” to twin girl group Prussian Blue and a member of Pioneer Little Europe, an organization of whites-only intentional communities — began showing Holocaust denial films at the Whitefish library. Or this past December, when a neo-Nazi site, the Daily Stormer, launched a campaign to troll local Jews as revenge for perceived attacks on the mother of “academic racist” (and Whitefish resident) Richard Spencer.

In the post-election tumult, the story of the troll storm quickly made the national news. A neo-Nazi march was threatened. Counterprotests were declared. Residents of Whitefish had to decide: How could they fight hate, and definitively declare their town infertile to the messages of these groups, without defining the town in the public imagination by that fight?

These questions concern more than just the residents of this rural corner of Montana. The online trolls who threatened Whitefish may have been terrifying in their anonymity, but like other fascists and neo-Nazis, they were easy to decry. Meanwhile, other forms of hate — more subtle, and more culturally normalized — flourish, virtually unassailed, across the nation. Moving forward, Whitefish and other towns will have to ask themselves: When does hate cross a line, and what responsibility does a community, and the nation that witnesses it, have to react when it happens?

Hate can gather in the most banal of places. Like a conference room at the Kalispell Hilton Garden Inn, outfitted with about a hundred chairs, a simple podium, and bad ’90s carpet. That’s where Chuck Baldwin’s church, Liberty Fellowship, gathers every Sunday from 2 to 5 p.m., and where his message is livestreamed to hundreds of loyal followers across the country. On a Sunday in January, the service started with a haunting hymn, sung in harmony by several women, before Baldwin took the pulpit to preach, without notes, for two hours.

Baldwin looks like a mix of a church dad and a real estate agent: He has a thick head of golden hair and a Mona Lisa smile that looks kind from one vantage point, scheming from another. For 35 years, he helmed a church in Pensacola, Florida, where his anti-gay, anti-abortion, fundamentalist preaching drew thousands.

Baldwin believes the South should’ve won the Civil War. He believes that the “castrated churches” of America are terrified of “Judaizers” and hamstrung by political correctness. For his various explicitly homophobic, anti-Semitic, and anti-Muslim preachings, Baldwin and his church have been designated an extremist group by the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Hate can gather in the most banal of places.

But Baldwin believes he is not a racist, and he declares as much on his website. A section entitled “Is Chuck Baldwin a Racist?” features a single video testimony from a black man who, according to Baldwin’s caption, grew up in the church. When I visited, there were more people of color (at least eight) than I’d seen elsewhere in the valley. A Hispanic family had driven an hour to visit the church for the first time. “I didn’t know you all were so close by,” the father told a greeter. “I’ve been listening for months.”

In 2010, Baldwin decided he and his extended family needed to relocate to a place that truly understood the meaning of freedom, and where he and his flock could ready themselves for the fight to come. “America is headed for an almost certain cataclysm,” he wrote. “We believe that this cataclysm will most certainly include a fight between Big-Government globalists and freedom-loving, independent-minded patriots.”

True liberty, Baldwin believed, could be found in the Flathead Valley — where he could stockpile arms, proselytize that “there is no liberty without the semi-automatic rifle,” and preach against the evils of gay people, Islam, Israel, moderate Republicans, and abortion. Inside the two entrances to the conference room, two large men positioned themselves for the duration of the service. Call them ushers, call them bouncers, call them people who wanted to make sure no one came and took issue with what Baldwin was preaching. The parking lot was filled with four-wheel-drive vehicles plastered with bumper stickers for Liberty Fellowship and “The Trump Train.”

Still, most people in Kalispell haven’t heard of Baldwin. They might have heard of church attendees like Randy Weaver (made infamous by the 1992 Ruby Ridge standoff in Northern Idaho) or Gaede, who has taken to online neo-Nazi forums to encourage readers to flock to the area. But that sort of anonymity is part of the point: Baldwin aims to build a mini civilization, free from any oversight other than his own — and God’s.

The Flathead Valley represents the “convergence” of two strains of Pacific Northwest extremism: antigovernment “Patriots” (distinguished by extreme prepping, weapons caching, and, oftentimes, a belief that they live outside the law) and white supremacists. It’s difficult to know just how many neo-Nazis, fascists, and adherents to other designated hate groups live in the Flathead Valley — there are dozens of names associated with just as many movements. But it wasn’t until 2010, when Gaede and fellow Pioneer Little Europe member Karl Gharst began screening Holocaust denial films at the Kalispell library, that an opposition began to emerge.

Oppositional protests, ad hoc at first, were headed by Reverend Darryl Kistler (then pastor of the United Church of Christ), Allen Secher (then rabbi of Bet Harim, the valley’s only synagogue), and Secher’s wife, Ina Albert. Later, under the name of “Love Lives Here,” the group moved on to offer educational events, including the now-yearly Martin Luther King celebration, an elaborate, star-studded production that is anything but a high school play.

Love Lives Here has a board of directors, but as Paige, a thirtysomething with an undercut who handles administrative duties, told me, it’s not a group with meetings so much as a mailing list with a suggested $30 member fee. As an independent affiliate of the Montana Human Rights Network, Love Lives Here’s primary role is to “envision the Flathead Valley as a caring, open and inclusive community.”

In December, that task included coming to the defense of a local real estate agent, her husband, their child, and two local rabbis, who had become targets of a “troll storm” instigated by the Daily Stormer.

The story of how that storm began to brew is complex and contested, but it goes something like this: In 2007, Richard Spencer had dropped out of his PhD program at Duke to pursue, in his words, a “life of thought crime” — a dressed-up way of saying that he was devoting himself to propagating fascist, racist, white nationalist ideals via various media publications, foundations, and quasi think tanks. In 2013, Spencer moved full-time to Whitefish, taking up residence in a $3 million “Bavarian-style” mansion owned by his parents, William (a wealthy ophthalmologist) and Sherry.

Spencer is tall and, as many profiles have gone out of their way to emphasize, handsome, with the practiced, articulate garrulousness of the grad student he once was. He is obsessed with creating an image of fascism that is the opposite of the bedraggled, tattooed, backwoods vision most associate with neo-Nazism. When Spencer posed for a New York Times profile last summer, he was fastidious about the details of his hair, his pose, his clothing. Recently, Spencer was punched by a protester after Trump’s election; as he scurries away in the now-viral video of the encounter, the first thing he does is fix his hair.

Spencer maintained a relatively low profile in Whitefish, at least until 2013. While riding a chairlift at Whitefish Mountain, Spencer started a fight with a conservative lobbyist, berating him for believing in “this whole democracy BS.” After some back-and-forth, the lobbyist forced the exclusive Big Mountain Club they both belonged to to decide: this racist, or me. The club initially chose Spencer — and the story got picked up by the national press. (Spencer was later asked to resign his membership.)

Back then, Donald Trump had yet to enter the political sphere, and the threat of what would come to be known as the alt-right, including men like Spencer, seemed minimal — even humorous. No matter that Spencer had been deported from Hungary and given a three-year travel ban in Europe for trying to organize a white nationalist conference: That was ridiculous extremism, and it would never take hold in America. Love Lives Here’s attempt to ban Spencer from doing business in Whitefish culminated in a compromise: The city council adopted a nondiscrimination resolution, but Spencer, and his publishing business, could stay.

For the next two years, Spencer continued to base his operations in Whitefish. He became an object of public fascination after a series of profiles highlighting his brand of “academic racism” and the concurrent rise of the so-called alt-right — a term he is said to have coined himself.

At the same time, Trump’s campaign worked to inflame xenophobic tendencies across the electorate. Trump did not explicitly align himself with white nationalism, yet Spencer, along with other neo-Nazis and hate group leaders, aligned themselves with him, hailing his presidency as the long-awaited turn from multiculturalism and political correctness. “I think if Trump wins we could really legitimately say that he was associated directly with us, with the ‘R’ word [racist], with all sorts of things,” Spencer told Mother Jones in October. “People will have to recognize us.”

Like nearly all of Montana, Flathead County voted overwhelmingly for Trump (65% of 46,250 votes cast). White nationalist Taylor Rose lost the race for the Montana House of Representatives’ 3rd District, located just a few miles from the Flathead County line, by just six points. Against the backdrop of a reported spike in hate crime reports across the nation, a clip of Spencer giving a Nazi salute and declaring “Hail Trump, hail our people, hail victory!” at an alt-right conference in DC in November went viral.

On December 5, Whitefish Mayor John Muhlfeld issued a proclamation to a packed chamber: “The City of Whitefish repudiates the ideas and ideology of the founder of the so-called alt-right as a direct affront to our community’s core values and principles,” he said. “As mayor, let me assure you — everyone is welcome in Whitefish.”

In the aftermath, a set of conversations took place between Sherry Spencer and a local real estate agent about the possibility of her selling a mixed-use building and publicly refuting the ideologies of her son. Details of what transpired rely heavily on Spencer’s own account of events, which she published, along with emails from the real estate agent, on Medium. Spencer argued that the agent was effectively extorting her, threatening to arrange a wide-scale protest in front of the building unless Spencer sold it and issued a statement of denunciation. (The emails deserve a close read; they seem not to suggest extortion so much as sympathy.)

The agent has not told her side of the story, but sources close to her offer a different take. According to them, Spencer began conversations out of fear that her business and/or status in the community had become imperiled because of her son; the agent simply suggested potential means of redress. Spencer then reversed course and posted her version of the story, positioning herself as the victim of zealous PC attacks, online.

Daily Stormer editor-in-chief Andrew Anglin seized upon this accusation, setting his trolls on the real estate agent, her family, Love Lives Here, the local Jewish community, and anyone who had (or might have) connections to them, including a local soap maker, an antique shop, and a café — at least until they figured out that the café owner’s Jewish-sounding name was not, in fact, Jewish. When the story was picked up nationally, Anglin claimed the “Lying Jew Media” was incorrectly portraying his site’s campaign against the Whitefish “Jewish racketeering cabal” as “threatening.”

April Gaede had been heard around town complaining, "What’s the problem with these new Nazis?!?"

So Anglin redoubled his efforts: If the real estate agent did not apologize, followers of his site, including “skinheads from San Francisco” and “a member of Hamas,” would descend upon Whitefish for an armed march in January.

On December 30, Richard Spencer posted a video requesting the end of the “Whitefish race controversy.” He didn’t want his own idyll — where he still skied and lived with his (now-estranged) wife and their young child — spoiled. Still, he downplayed the seriousness of the threat: “I’m not telling Anglin to do anything,” he told the Missoula Independent. “I just assumed it was a troll. Can he really bring out people for a march on a ski village in remote Montana?” (Spencer also said he would not be bullied into leaving Whitefish. “I’m not going to obey them,” he said, referring to Love Lives Here. “I might stay here to piss them off. I’m dead serious.”)

But Anglin wasn’t backing down, even if it made Spencer look bad. That’s the thing about the far right: It’s easy to group them together at one extreme, but they are, in many cases, at odds, united only by convenience and their onetime support of Trump. (April Gaede had been heard around town complaining, “What’s the problem with these new Nazis?!”) Spencer fancies himself more sophisticated, erudite, and palatable than Anglin; Anglin believes something along the lines of “Richard Spencer can go fuck himself.”

In an addendum to her Medium post, Sherry Spencer also requested that Anglin desist — but trolls, once set in motion, are nearly impossible to stop. Their power, after all, stems directly from their unruliness. Usually, that unruliness is limited to online harassment, with periodic entrances into real-world harassment.

Anglin filed a permit for a “James Earl Ray Day Extravaganza,” to be held on Martin Luther King Day. But his planned route, which included a nonexistent “Jewish Community Center,” made little sense; according to city manager Chuck Stearns, he did not include the proper fee for an event of its size, nor did he secure the necessary insurance or permission from businesses along the route.

His permit request denied, Anglin announced that he’d called off the buses scheduled to carry the “skinheads” from San Francisco. He promised to consult the ACLU and launch a case against the city for prohibiting the march. (He didn’t.) They’d march in February instead, Anglin said. Just you wait.

Days before the trolls had planned to descend on the town, Whitefish remained on edge: Who knew whether Anglin was bluffing? The online Nazis might not show up, but others, including those living closer by, still might. Threats hold power whether they come true or not — just like hate is real, whether it’s manifested online or off.

“It’s been so horrible,” Lisa Jones, the public relations manager for Explore Whitefish, told me at the Firebrand, a glossy new hotel on the edge of downtown. “Anglin has controlled my life for the last six weeks,” she said, referring to the way he’s both attacked the town and held it in suspense over whether or not the march would go on. “He’s the puppeteer and I’m the puppet. That’s what’s really infuriating.”

Jones wore a version of the unofficial uniform for women over 20 in Whitefish: thick wool tights and stretchy skirt paired with several layers of fleece and down jacket. She moved to Whitefish in 1989, back before the millionaires discovered it, when you could still buy a house for $40,000. Today, she has the frazzled look of someone whose life has been consumed by weeks of warding off attacks from bored, anonymous, spiteful people on the internet.

Trolls, once set in motion, are nearly impossible to stop.

In 2010, Jones had watched the controversy over the screenings at the Kalispell library, but it hadn’t directly affected or threatened Whitefish’s tourist economy (which, as of 2015, topped $635 million). Tourists come from Seattle, first and foremost, but also from California, Minnesota, Texas, and all up and down the East Coast. Montana lives in their imagination as a place of wide-open spaces and unrivaled beauty, not the home of extremism and hate.

That is, until Spencer started mentioning Whitefish in interviews — in at least 25% of his conversations with mainstream outlets, according to a spreadsheet personally maintained by Jones. Still, calls from tourists didn’t start coming in earnest until the troll storm — and the national coverage of it — erupted. “I’ll have people contact me from Dallas, wondering if it’s still safe for them to come for their ski vacation,” Jones said. “But we reassured them.” Tourists visiting from Idaho, which had its own battle with neo-Nazis and extremists in the ’90s, might understand that the extremist views do not define the city. But it’s harder to convince someone who’s never been to this tiny town in the middle of the wilderness that it is safe.

“They only see the story about Spencer and those trolls,” Jones said. “They don’t see the way this community wrapped their arms around those who were attacked. How, the Thursday before Christmas, we announced that people could drop off their cards and gifts of solidarity and support, and those baskets overflowed with gifts, wine, food, homemade crafts, cards and notes and letters — even for Sherry Spencer.”

Businesses posted “Love Lives Here” stickers in their windows and images of menorahs, printed by the local newspaper in homage to the nationally publicized fight against anti-Semitism in Billings, Montana, during the ’90s. When trolls bombarded the “soap lady,” as she’s become known, for her association with the real estate agent, supporters purchased more soap from her in a month than she usually sells in a year. When trolls began leaving fake reviews on restaurants’ Yelp sites (“I found a cockroach in my burger”), townspeople left positive ones to drown them out.

Now, when a tourist emails or calls with a concern, Jones and other community leaders have a strategy. “You don’t want to call attention to it if someone doesn’t know about it,” Jones explained, “but the messaging is there.” A message, in other words, that everyone is welcome in Whitefish.

That was the message of the “Love Not Hate” rally that took place a week before Anglin’s planned march and attracted thousands from the Whitefish community. “We started thinking about it right after the election,” co-organizer Jessica Loti Laferriere told me at a Whitefish coffee shop where, just the week before, Spencer had held court while the Missoulian snapped photos.

Laferriere and her co-organizer, Dominica Cleveras, had become frustrated with the media’s focus on the hateful and divisive beliefs within the valley that didn’t actually represent most of its residents. Beliefs like those of Spencer and Gaede, of course, but also those manifest in moments of casual prejudice at the local high school, like a student telling a substitute teacher from South America to "go back to Mexico."

“We thought, 'Maybe we’ll have 100 people come, max?'” Laferriere said. But after Anglin’s call to action, the event swelled to at least 500. There were food donations, and a warming station, and chair massages and a kids corner and a photo booth and sprawling coverage in the local papers. It was, as one Democratic Socialist who attended the protest put it to me, “very kumbaya.”

A week after the Love Not Hate rally, several dozen people gathered at the Outlaw Inn in Kalispell for a film screening hosted by ACT for America — one of the very groups that Love Not Hate wishes to counter. ACT for America was founded in 2007 to, in its own words, “promote national security and defeat terrorism.” In practice, this means lobbying for anti-Sharia legislation, fighting immigration and refugee resettlement, and spreading the idea that Islam is a hateful ideology — not necessarily a religion, or subject to protection under the Constitution.

ACT currently claims membership of around 400,000 (although that number cannot be confirmed), with 1,000 chapters, some dormant, across the United States. It is officially nonreligious, although it strongly supports the Israeli state, and is officially nonpartisan, although General Michael Flynn, Trump’s recently appointed national security adviser, who has publicly referred to Islam as a “cancer,” sits on ACT’s board of directors.

In the Kalispell conference room, the atmosphere was welcoming — at least to a white woman. On one table, there were cookies and coffee; on another, a suggested reading list (including Because They Hate: A Survivor of Islamic Terror Warns America, written by ACT’s controversial founder Brigitte Gabriel, a Lebanese Christian) and a handout with “facts and statistics on refugee resettlement” (“13% of Syrian refugees have positive feelings towards the Islamic State terrorist group”).

I sat next to a middle-aged guy dressed in a Carhartt vest, sturdy jeans, and work boots — which, in Montana, could’ve marked him as a rancher or an orthopedic surgeon. He asked if it was my first time, and whether I knew the score for the Seahawks game. “You’ll find this all very informative,” he told me.

"We are against illegal immigrants, we are against people who cannot be vetted, who come here with diseases and then we have to deal with the problem.”

The meeting was called to order by a prim woman named Caroline Solomon, herself a Belgian immigrant. Speaking with a thick accent, Solomon attempted to clarify the group’s principles: “We are not against immigrants, we are not against refugees — there are a lot of them we should help. We are against illegal immigrants, we are against people who cannot be vetted, who come here with diseases and then we have to deal with the problem.”

Solomon introduced Tom Osborne, a grandfatherly man whose interest in Islam first developed during his time with the LAPD, when he was involved in a 5.5-hour “gun battle” with the Black Panthers in 1969.

Osborne introduced the day’s screening: Islam Rising, a repackaging of far-right Dutch politician Geert Wilders’ infamous, inflammatory anti-Islam documentary Fitna, which argues that Islam is forcefully colonizing European culture and values. After the screening, Osborne conducted a question-and-answer session, elaborating at length on one of the central arguments of his teachings: that there is no such thing as a moderate Muslim.

“Jihadists are 10% of the 1.5 billion Muslims in the world,” Osborne said, his cadence measured and professorial. “Probably more. And 10% of 1.5 billion Muslims is 150,000 Muslims who will do whatever it takes to change the way you, your children, and your grandchildren live. It is the largest militant force in the history of this planet, even at just 10%.”

The audience listened in rapt silence as Osborne elaborated on the way that Islamists, which he estimated at another 10% of the Muslim population, “provide fertile ground” for jihadis.

“Now, does that leave 70% or 80% of of the world as so-called moderate Muslims? Muslims who are not a threat? Well, yes and no. They will not speak out against what the other 20% are doing — because it is apostasy in their faith to do so. It’s the death penalty. So they acquiesce with silence, which makes them passive terrorists. Those 70% or 80% of Muslims in the world — are they committed to killing us for being infidels? Probably not. But they’re sort of guilty of acquiescing to it. So there are no innocent Muslims.”

“There has got to be a significant percentage of Muslims in the United States who look around and see everything their religion is not,” Osborne said. “The freedom, the peace, the light, the forgiveness, the choices — all the things we take for granted. None of these things are available to them in their dark, restrictive world of Islam. It’s a world of nothing but restrictions and fear ... There’s no light, there’s no peace, there’s no love, there’s no forgiveness. It is a black religion.”

Osborne and ACT’s dark vision of Islam is shared by Steve Bannon, who infused Trump’s campaign — and, now, executive orders — with its tenets, including, as one scholar of Islamic studies put it, “a master narrative that pits the Muslim world against the West,” a sort of 21st-century version of the Crusades.

This vision is particularly effective in places with few or no Muslims, like Flathead County, and those in proximity to cities with a recent influx of Muslims. Places like Missoula, Montana, which started accepting refugee families in March, sparking ardent assurances from surrounding counties that they would reject all attempts at refugee resettlement. At the ACT meeting, Missoula's refugees were mentioned with great derision — but no mention was made of the fact that of the 17 families that had arrived in Missoula since March 2016, five were Congolese Christian and six were Eritrean Orthodox Christian. Only four families — two from Syria, and two from Iraq — were from Muslim-majority nations.

Halfway into the Q&A, the conversation shifted to Whitefish and the events of the last month. “Right here in our own Flathead Valley, we have Love Lives Here,” a woman named Linda said. “And when this whole thing came up with Mr. Richard Spencer, the, uh...”

“White supremacist!” someone in the crowd shouted.

“Yes, the white supremacist,” Linda continued. “We’re Montanans. We’re fair and loving people. We don’t tolerate that, and we won’t tolerate that. But [Love Lives Here] made Whitefish the talk of the world, I saw it everywhere — CNN, all over. They made Whitefish look like it’s home to racists.”

The crowd murmured in agreement.

“They’re very pro-Muslim,” Linda said, referring to Love Lives Here. “And anti-Israel ... We have to fight them, because they’re trying to silence us.”

Talking through applause, Osborne complimented Linda on her question. “There’s a great, to me at least, hypocrisy in that movement,” he replied. “On the one hand, they don’t want that kind of intolerance towards a race or group of people to be exhibited. But they support, as you stated, the most historically intolerant theology in the world. They support Islam. Now, you can’t have it both ways. Either you’re against discrimination of that sort or you’re not.”

In dire tones, Osborne warned the crowd to remain vigilant — but not against Muslims so much as laws that would curtail criticism of Muslims.

“We have a false sense of security here in Montana,” Osborne said. “We think we’re so safe and secure from the horrible realities in the other world, in California, but we’re not. We talk about free speech, for example, and how they will do anything to close the door with things called ‘hate speech laws’ that prohibit the criticism of Islam. So how safe are we? The summer before last, a hate speech law came within one vote of passing the city council in Billings, Montana.”

“Right. Here. In Mon-tan-a,” Osborne said, drawing out the name of the state. “It could happen everywhere.”

On Martin Luther King Day in Whitefish, the sun didn’t rise until 8 a.m. The temperature inched from 5 to 10 degrees as I drove the 20 miles from Whitefish to Kalispell, and pockets of sun poked through the fog blanketing the valley. When Anglin first announced the march, at least a half dozen groups sprang into action. Rebecca Schaffer, an effervescent playwright and director who’d founded Whitefish’s one and only cabaret, had spent the last month attempting to coordinate communication between them. Schaffer wanted a passive, peaceful, possibly artistic form of resistance. Another group planned a Matzo Ball Soup Brigade. A group from Missoula wanted to “troll the trolls,” in blue troll wigs. The Anti-Fascist Group, better known as Antifa, advocated direct action.

Schaffer suggested I reach out to Adam Langer, who was coordinating a different faction on Facebook, mostly from the Kalispell area, who wanted to stand in the street and block the march.

“I’m not a leader,” Langer told me from his office at a local car dealership, a classic rock station playing in the background. “I’m just the guy who put his name on the Facebook group.”

“We just want to stand in the street and block their way,” he said. “We’re not looking for a fight. But some of these other groups, they’re like, if we have matzo ball soup there, they will just put their guns down and just eat soup. And it’s like, no, they won’t.”

Langer laughed, leaned back in his chair. “There are so many opposition groups. But they’re all from somewhere else! From Missoula, from Washington, from Helena — and it’s like, we live here.” Still, Langer was willing to let everyone have their own mode of protest.

“I’ll put this way. When I was in Whitefish at that meeting, Trump’s name got brought up more than once,” he said. “I voted for Trump, and I am proud to say that I voted for Trump. Most of the liberal opposition are the ones who don’t actually want to do anything if Anglin comes. The non-liberals are the ones who actually want to stand in his way.”

Back in Whitefish, the downtown had the feel of a tensed and tiring muscle. There was an hour before Anglin’s planned march time — 3 p.m. — but residents had already phoned the police, concerned about people walking the streets in all black, with pink armbands. (They were members of the Queer Insurrection Unit, up early from Missoula.) On the road into town, someone had stapled a fluorescent poster-board sign to a telephone pole: “DIVERSITY IS BEAUTIFUL.”

A man leaned out of his window and yelled, "Have you seen any douche Nazis yet?"

A small group formed near Depot Park, mostly composed of members of Antifa, the Alliance for Intersectional Power (formed at Standing Rock), and the IWW (better known as the Wobblies, a century-old union with deep roots in Montana). A guy in his twenties, shivering in a shearling jean jacket, recently moved to the valley to work the train yards after spending time as a roughneck in North Dakota. A contingent of 20 had caravanned five hours from Spokane, Washington, led by Native American activist Jacob Johns.

Two protesters, their faces obscured by black scarves, described themselves as “anarcho-communists,” committed to direct action. “Anglin and his trolls are such flakes,” one of them said. “We’re here because we stick to our word.”

An SUV drove by, honking. A man leaned out his window and yelled, “Have you see any douche Nazis yet?”

A group spilled out of a car and began slipping on blue troll-hair wigs. They offered me a nine-page document explaining the inspiration, roles, and praxis of their satirical protest, Trolls Against Trolls. Josh Manning, a member of the Progressive Vets who lives in Helena and works as a civil rights investigator, had driven four hours from Helena. “I’m a secular Jew,” he said. “Part of me didn’t want to come, though, because I’m not from Whitefish. But Montana is one big small town.”

Down the street, the Matzo Ball Soup Brigade were setting up their soup station. Rebecca Schaffer bustled between groups, collecting designated reps from each in a circle. “Can we all put in our numbers so we can communicate on WhatsApp?” she asked. “We only use Signal,” one of the Antifa members responded, referring to the end-to-end encryption service.

As the leader of the Antifa group, who goes simply by “Strider,” began to read a declaration of principles, two police officers arrived on the scene. The protesters could assemble on the street, the police told Schaffer — who had become the de facto mediator between the outside protesters and the city — but they couldn’t use the bullhorn. Adam Langer stood a few steps away, coffee cup in hand, observing the scene with a look of bemusement.

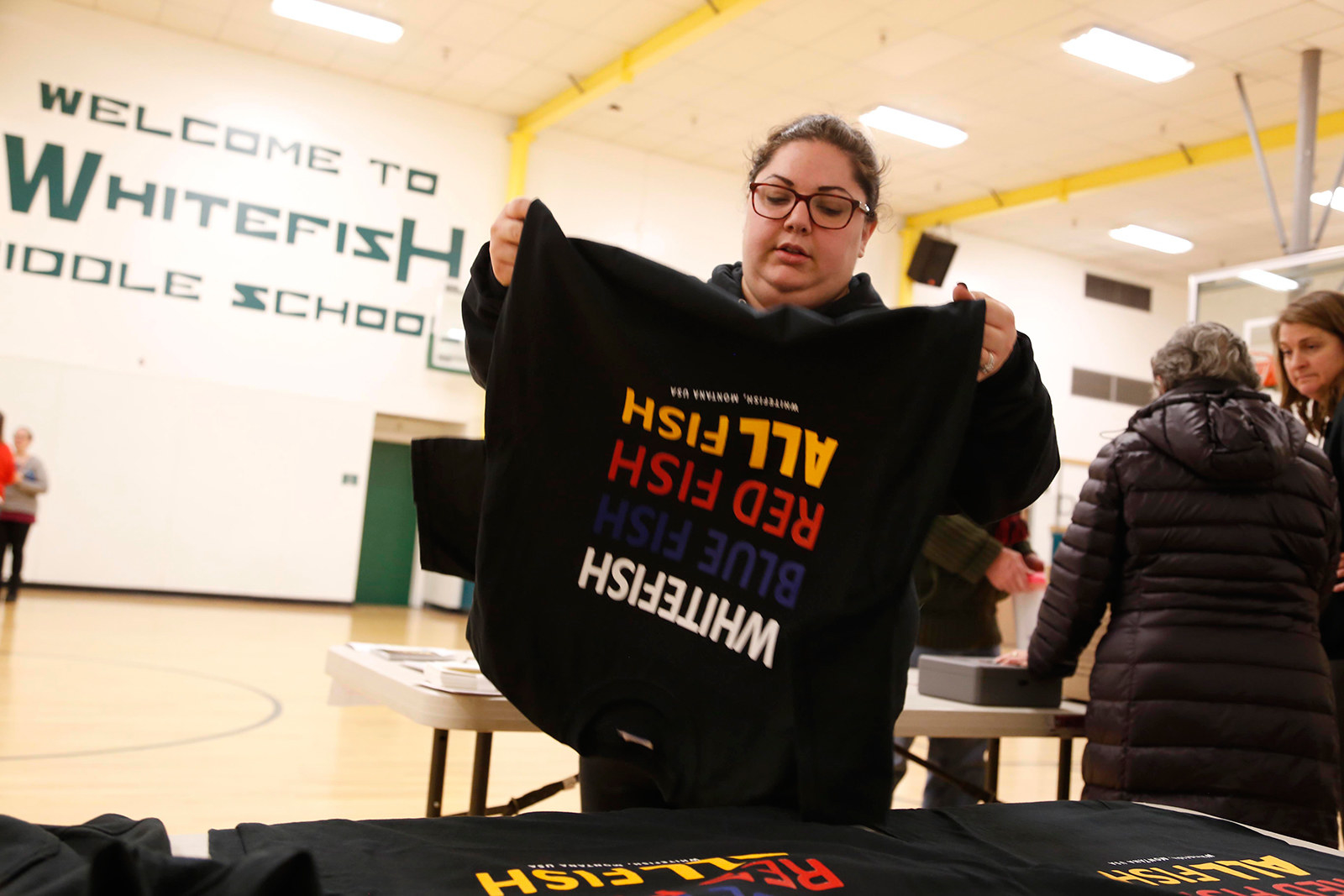

The time allocated for the Nazi march came and went; the protesters shivered and stamped their feet to keep warm; cars kept honking their horns as they passed. Gradually, the various factions dispersed: most back to Missoula and Spokane, others to the middle school gym, where a family activity fair sold shirts that read “WHITEFISH BLUE FISH RED FISH ALL FISH.”

A few hours later, locals packed the auditorium of the local arts center for the Martin Luther King Day celebration. The Crown of the Continent Choir, composed mostly of what one local lovingly called “the silver-hairs,” sang “One Voice.” When Rabbi Francine Roston rose and, through tears, praised the city at large for wrapping its arms around those who’d been targeted by the trolls, it felt like the several hundred in attendance were engaged in a collective, deeply therapeutic group hug.

In Whitefish, the events of Martin Luther King Day were a fitting end for the last weekend of an Obama presidency: a harbinger of both a dormant, spirited resistance and the reality of a newly empowered strand of American intolerance. Like the Women's March and airport Muslim ban protests that would soon follow, that Monday in Whitefish offered a reason to be hopeful, coupled with a sobering truth: you only needs to be reminded that "love lives here" if hate does too.

There's no question that love, does, indeed live in Whitefish — and that the town has forcefully rejected the rhetoric of hate associated with its most extreme residents. But something else, something quieter and less immediately dismissible, lives there as well. It’s there in the gas station manager who tells his employees not to serve people with license plates that indicate they’re from the Blackfeet Reservation. It’s there in the casual misgendering of a queer woman, three beers in, and the comments and stares that follow her through the night. It’s there when people second-guess the credentials of a local orthodontist, simply because he’s Korean-American. And it’s there in the nice-looking white ladies nodding their heads to the phrase “Islam is a black religion.”

For certain types of misfits and social outliers, Montana is a paradise. For others, it's a place where every day is a matter of weathering a kind of banal, smiling bigotry. There’s quite a difference between defending your town from outside interlopers and making it hospitable to people who are not white or straight or from a Judeo-Christian background. It’s the difference between creating a safe space for tourists to visit for the weekend and making the larger area safe for anyone to, well, live their lives, if they don’t look or live or love or worship like the people who’ve lived there for decades.

Describing the difficulties the valley still has with intolerance, Jessica Loti Laferriere, the kindergarten teacher who put on the Love Not Hate rally, put it simply. “Part of the problem is that there are no Muslims who live in this area,” she said. “So how do we support them?” And how do Muslims — along with refugees, and trans people, and undocumented immigrants, and even black people — become real people, not abstract concepts, to those inclined to reject them?

As the Missoulian editorial board explained, “Hatred is not isolated to one man in Whitefish, or even to one fringe group. We see it, not every day, but often enough to dishearten us, whenever the Missoulian reviews letters to the editor or online comments that are simply too prejudiced to publish. Our readers never see these letters, and thus remain unaware, perhaps, that their neighbor, their favorite business owner, their colleague holds these views.”

The situation that devolved around Richard Spencer in Whitefish was specific to the town, its history, the moment in time, its inhabitants. But there are so many other places, with so many other potentially incendiary combinations, that could incite explicit action from trolls, fascists, and racists. “The problem isn’t that Spencer lives here,” Lisa Jones told me, shaking her head. “It’s great that the march was called off. But this fight’s not done. It’s a marathon. Every day, we just have to keep building community.”

Fighting hate isn’t just printing signs or showing up to a protest. Nor is it denouncing Spencer — or even punching him. It’s no single action or stance or belief. The best strategy I heard was offered up at a sleepy Sunday service at the United Methodist Church, the day before Martin Luther King Day. “If we’re not providing ideologies that provide people with answers,” Pastor Morie Adams-Griffin asked his congregation, “what other groups are? The white supremacists — the white nationalists. So why aren’t we the ones providing answers for those who are hurting?” ●

CORRECTION

Liberty Fellowship was located in Pensacola, Florida. An earlier version of this post misstated the location.