When eight people were shot at Burnett Chapel Church in Burnett, Tennessee, last week, an Idaho man posted a link to a news story on the shooting. “My church is a ‘Guns Welcome’ church,” he wrote. “I pity the fool who would try something like this there.” This man, a Facebook friend whom I won’t name here, is a proud gun owner; in fact, he moved to Idaho in part because it’s easier to own and carry guns there.

This friend articulated one of the main reasons why the gun control debate remains at an impasse even in the aftermath of dozens of mass shootings, including an attack on Sunday night at a country music festival in Las Vegas that killed more than 50 people and injured hundreds. Specifically: the deeply held belief, among many people in this country, that evil men with guns should be countered with righteous men with guns — or that evil is uncontrollable. It’s the same idea that guides the training of teachers to wield rifles in a rural Idaho town and that allows the concealed carry of firearms on Idaho college campuses. At a public meeting held last week in Idaho, I saw the telling bulge of at least three concealed weapons.

This philosophy is not limited to Idaho: All 50 states permit concealed carry; 23 states allow individual institutions to decide gun laws on their campus; 10 additional states mandate that concealed carry must be allowed (with specific provisions). Most of the laws that permit guns on campus — or reverse bans on concealed carry — were introduced and passed in the aftermath of the Virginia Tech shooting in 2007. It’s the pro-gun version of gun control: Protect Americans from bad people with guns by allowing more guns to circulate.

One side believes in the responsibility of the group to put controls in place that protect its individual members. The other believes, above all else, in the rights of the individual.

Whether or not you believe that philosophy, you can see how fundamentally discordant it is with the liberal belief that restrictions on access to guns — whether banning certain types of guns, mandating waiting periods, preventing certain individuals from obtaining guns, or eliminating public ownership of guns altogether — will decrease mass shootings, accidental shootings, homicides, and even suicides. Data, and comparisons to countries with tighter and/or complete gun control, supports these claims. Thus the declarations that percolate across social media after every mass shooting: “Why does anyone need a gun like this?” “Why do we keep letting this happen, when there’s an obvious solution?”

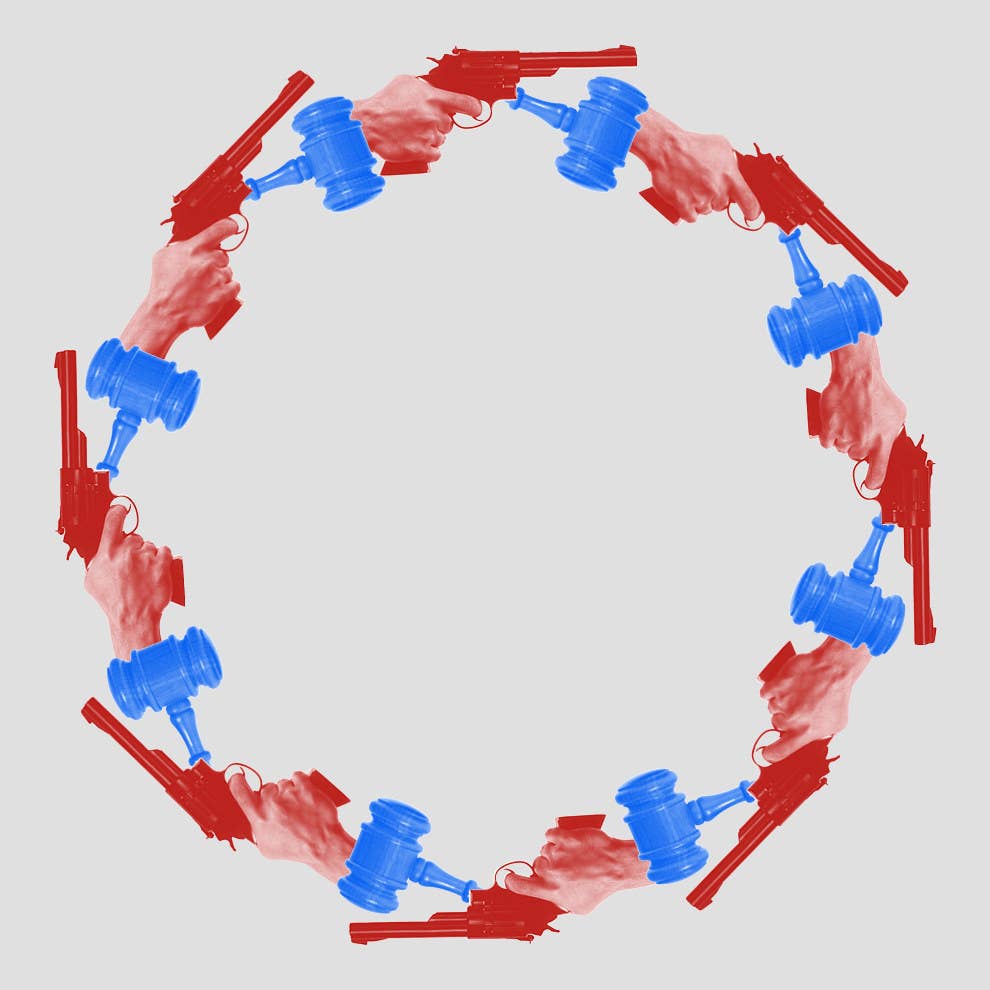

With each mass shooting — and there have been 273 in 2017 alone — these oppositional philosophies harden. The same conversations, statistics, accusations, videos, memes, and, as Jamilah Lemieux put it on Twitter, “vague chatter about the mentally ill that doesn’t lead to any action other than further stigmatizing the mentally ill,” cycle through the media, then go dormant until the next mass shooting reactivates them.

The impasse remains, at least in part, because these discussions of gun control don’t really address the deeper, seemingly intractable difference between the two sides — one that has everything to do with the way that each conceives of individual agency. Simply put, one side believes in the responsibility of the group to put controls in place that protect its individual members. The other believes, above all else, in the rights of the individual. What we’re not talking about when we talk about gun control is just how difficult it is to for these viewpoints to meet in conversation.

For those opposed to government-mandated gun control, no limit will actually inhibit an individual who is set on committing violence. To impose any of those strictures, even on people with mental illnesses, would limit the inalienable rights of all citizens — making many answer for the actions of the few. That’s why many gun advocates prefer to be called advocates for or “protectors” of the Second Amendment: Their answer to tragedy isn’t more regulation, but more freedom. (Those in favor of gun control would counter that the first inalienable right outlined by the Declaration of Independence is the right to life, which is impinged upon by those who abuse their access to guns.)

These attitudes align fairly precisely with the two sides of the political spectrum. Liberal ideology supports governmental regulation in the name of the greater good, for higher taxes that pay for social safety nets, for universal health care. Each of those ideas is rooted in the belief that what happens to one of us happens to all of us, and measures should be put in place to ensure the greater good.

On the other side of the ideological spectrum, the conservative stance is rooted in the individual’s ability and right to make decisions for themselves and their families, to decide how to spend the money they earn, to do the right thing, to use guns safely and correctly. One person shouldn’t have to have to pay for others’ mistakes, nor should their liberty be compromised because of the tresspasses of another. These ideas fuel the canny and successful messaging of the NRA, which calls itself “freedom’s safest place” and incites membership by warning that “our rights are under attack like never before.”

One position leans toward socialism, the other toward libertarianism, and our country has been built through compromises on both sides. The agreement that we’ll pay taxes that fund schools even if we don’t have children in them and the reliance on programs like Medicare and Social Security are all undergirded by a persistent belief in the American dream, which suggests that any person, of any race or religion or class or upbringing, can become a thriving member of society if they work hard enough.

The American democratic project survives through détente between left and right.

The American democratic project survives through détente between left and right, through the election of moderates who seem to reconcile both sides and extremists who balance each other out. It is often troubled, and never without conflict. But it endures, an assurance to voters that their philosophy of the country and their place in it remains intact.

But certain issues — Obamacare and gun control foremost among them — are increasingly treated by many conservatives as warning shots, threats to the integrity of the entire enterprise. Within this logic, a move to curtail gun ownership is a move to curtail liberty, full stop. That’s why so many politicians currently making inroads from the the far right label themselves “liberty-minded”: They have pledged to prevent the first rock from sliding down the slippery slope toward government control. They do more than pledge it — they make it a centerpiece of their campaigns. This then forces their opponents in both primary and general elections to pick a side, which often means reassuring people that they aren’t out to take away anyone’s all-American rights.

In the dozens of states that aren’t solidly blue, to come out for even limited gun control dooms you as a conservative candidate, and severely hobbles a moderate hoping for independent voters. When Montana Democrat Rob Quist ran to replace Ryan Zinke, the newly appointed secretary of the interior, in the House, on a platform that included the registration of assault rifles, he was painted as a gun control fanatic. Montana Sen. Jon Tester, a Democrat in a state that voted overwhelmingly for Trump, has repeatedly pledged to “stand up to anyone — Republican or Democrat — who wants to take away Montanans’ gun rights.”

These examples are deeply Montanan, and Montana, like so much of the Mountain West, is a state where guns do have a utilitarian role. But for hundreds of federal, state, and local legislators outside of liberal enclaves, to sign on to gun control — even in the wake of a tragedy as massive as the one in Las Vegas — would translate, come election time, as an effort not to protect the lives of others, but to curtail the freedom of all. The NRA, which contributed to the campaigns of 293 sitting US legislators and issues a “grade” to each candidate — works tirelessly to ensure as much.

On Monday morning, Connecticut Sen. Chris Murphy, a Democrat and leading voice in the gun control movement, tweeted the following: “To my colleagues: your cowardice to act cannot be whitewashed by thoughts and prayers. None of this ends unless we do something to stop it.” But there’s a reason that some are already floating the idea of Tester — a working farmer and “gravel road” Democrat who appeals to moderates on both sides — as the future of the Democratic Party.

Of course, some politicians could swallow their future personal defeat in the name of a greater law — that’s what dozens of Democrats did in order to get Obamacare through the House, knowing full well how their vote would be framed when they faced reelection. But that supposition returns us to the fundamental difference at the heart of the two positions and, by extension, two Americas: One believes in the ability of the government to create safety, even if it entails sacrifices, small and large, on the part of the individual. The other believes those sacrifices, and the incremental increases in safety they cannot even guarantee to provide, are simply not worth the compromise of their liberty.

We return to this bitter, circular debate because it’s not, at heart, about guns.

When Stephen Paddock opened fire in Las Vegas, Jason Aldean, one of the biggest acts in country music, was onstage. His current hit, “They Don’t Know,” is about the judgment people from cities pass on small towns: “They think it’s a middle of nowhere place where we take it slow,” he sings, “but they don’t know.” Country music is rooted in the virtues of ruralness, and plenty of artists have made brash hits out of small-town pride. But Aldean’s song is a somber, almost mournful one: “They don’t know a thing / About what it takes / Livin’ this way,” the chorus repeats.

There’s anger when people don’t understand your way of life — for instance, when then–presidential candidate Barack Obama declared that small-town resentment and economic anxiety had led citizens to “cling to guns or religion.” But there’s also an abiding sadness. The day after Aldean fled the stage, we return to this bitter, circular debate because it’s not, at heart, about guns. Through decades of Westerns, through the fetishization of the Constitution, through ideological maneuvering on the part of the NRA, guns have become signifiers — deadly ones, but signifiers nonetheless — of the American ideal of personal freedom. A gun rights advocate might not put it that way, but they would likely tell you, when you argue that no one “needs” a gun, or that gun control measures won’t impede upon the larger right to bear arms, that you just don’t get it.

This weekend’s shooting in Las Vegas, like the dozens of others over the past year, and the hundreds more over the last two decades, is a tragedy. On that, both sides agree. But people will continue to die until the two sides of the issue can actually have a conversation with each other. Like so many issues in American politics, this debate is ultimately driven by fear — of losing life, or losing a way of life. And until those on each side can honestly face what they’re afraid of, neither will feel safe. ●