"Far from the Bible Belt's conservative territories, in blue-state cities and suburbs, young, educated, married mothers find themselves not uninterested in the metaconversation about 'having it all' but untouched by it," writes Lisa Miller in this week's New York. These are the so-called "retro wives," women who could have high-flying careers but instead choose to stay home with their kids.

But at this point, Miller's story itself feels retro: The fascination with well-heeled women giving up work for family is decades old.

Ten years ago, Lisa Belkin gave the genre its most famous formulation with "The Opt-Out Revolution," her 2003 Times story on Ivy League–educated young women deciding to be stay-at-home moms. But the tradition of the opt-out story stretches back much farther — the Times published "Case History of an Ex-Working Mother" back in 1953. Such stories are now common enough that one expert in work-life law published an entire study of them, identifying 119.

Despite the reams of pages devoted to the subject, opting out has never been a real trend. The number of married women who leave behind successful careers to care for kids is a very small subset of the stay-at-home mom population. So why do these stories have such staying power?

Part of the impetus for opt-out stories is surely their pot-stirring potential; the subtext of these narratives is almost always that kids are better off if moms (and not dads) stay home with them full-time. And few things are surer to stir up controversy among the largely middle- and upper-class people who buy magazines and read The New York Times than suggesting they're raising their kids wrong.

But there's something else at work too: a genuine anxiety about how Americans lead their lives. Miller herself betrays it in her New York piece. She and her husband both work, she says, but "I yearn sometimes for the vast swaths of time [stay-at-home mom] Kelly Makino has given herself to keep her family's affairs in order." Balancing work and family is difficult, especially now that American parents are spending more time on both, and there's an undeniable appeal in the idea of choosing just one.

Especially when it looks so pretty. Makino, Miller writes, now spends her days taking the kids hiking and to museums, buying her husband dark-wash jeans, and preparing his favorite recipes, like "one for pineapple fried rice that he remembered from his childhood in Hawaii." Thanks to Makino's choice, the whole family's life is now Pinterest-ready. The opt-out story is aspirational.

The number of men who can provide in this style, however, is very small. Makino's husband Alvin supports their family of four on a "low-six-figure salary" — in 2011, only about 9% of American men made more than $100,000.

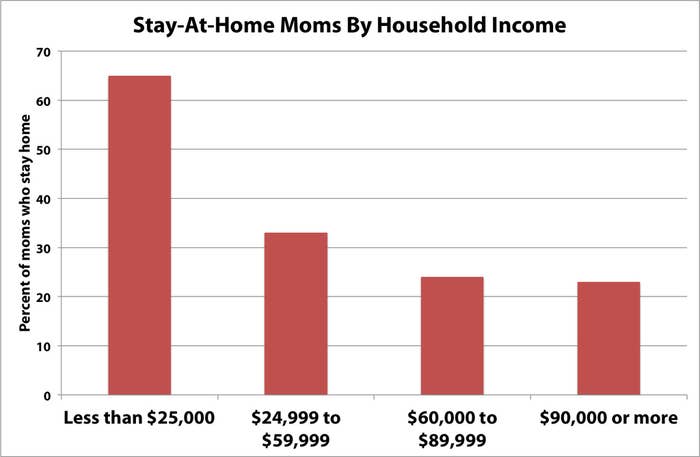

And most stay-at-home moms live on significantly less. According to a 2012 Gallup poll, the moms most likely to stay home are those whose household income is under $25,000 a year.

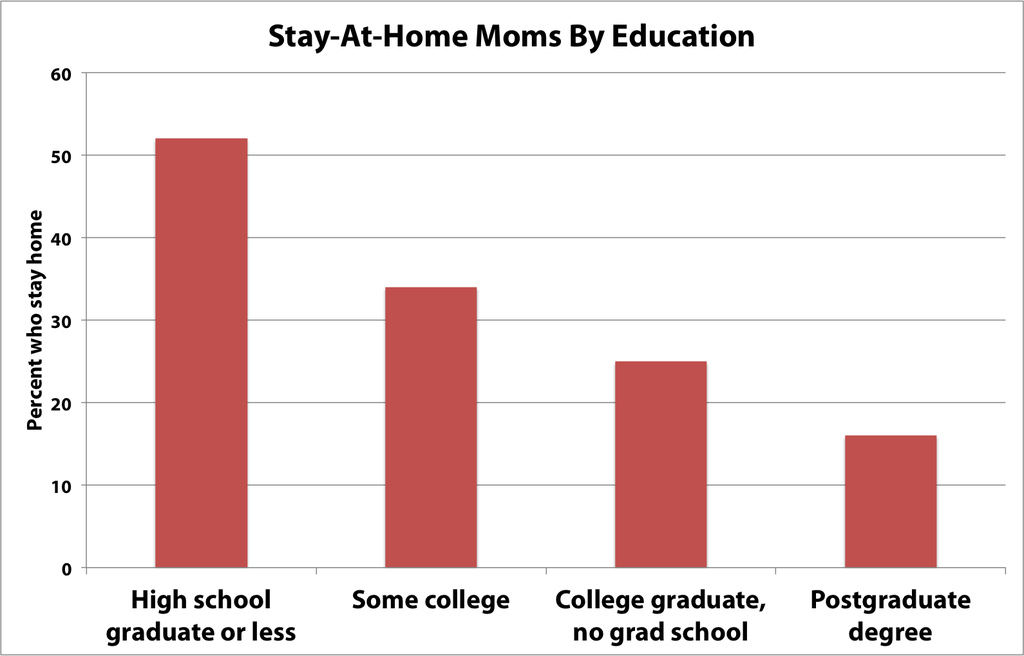

For these women, it's not about opting out. It's likely many of them wouldn't be able to earn enough to pay for child care if they entered the workforce. Moms are most likely to stay home if they didn't graduate from high school — just 31% of stay-at-home moms have a bachelor's degree or higher, according to a 2010 census report [PDF]. That report concluded, "there is no opt-out revolution changing the landscape of stay-at-home motherhood. Rather these data suggest a 'left out' group of married mothers who are young, Hispanic, and have less than a high-school education."

Focusing on the "left out" group — women who may have been laid off, who can't access maternity leave, or who can't earn enough to cover child-care expenses — raises serious questions about American public policy. These women may be clipping coupons, not buying designer jeans. Their husbands may be working multiple jobs to support their kids. They may be far from the serenity that Makino's choice seems to offer, and they may not have made a choice at all.

Ultimately, the opt-out story is a fantasy: that if women just made the right decisions, their lives could be worry-free. But the "decision" to live on one six-figure income is only available to a tiny fraction of Americans — for many more, raising kids is a struggle, whether Mom works or not. Tackling the reasons for that is a lot more complicated than stirring up one more mommy war. But it's also a lot more necessary.