Tessa Thompson has a problem. “I really like to be good at things,” she says, reclining in a rich brown leather chair in the Library bar of Manhattan’s NoMad Hotel. It’s a Sunday afternoon in March, and Thompson is wearing a sheer black blouse with gold-chained collar pins and high-waisted acid-wash jeans. “It’s an impediment sometimes.”

The idea that the 32-year-old could be impeded by anything seems unlikely. In the past two years, she has been touted as Hollywood’s Next Big Thing based on performances in films such as the indie darling Dear White People, the historical drama Selma, and November’s box office hit Creed, and she has parlayed those successes into at least three potentially life-changing upcoming roles. “To be really bad in the beginning and to risk being bad every time and just continually be compelled to want to be good and better?” she says, her Ts aspirated in the manner of a lifelong performer. "Acting is the only thing I was able to push through that."

And, as Thompson acknowledges, the roles she’s had a particular knack for so far have tackled complicated issues of race and gender — all befitting the multiracial actress, who peppers her musings with references to everyone from bell hooks to Laurence Olivier. “Whatever alchemy it is, those are the kind of parts that I'm going to be better at.”

Fortunately for Thompson, those roles have been of particular importance in Hollywood in the past few years. Consider the critical and financial success of films like Creed, Selma, 12 Years a Slave, and Straight Outta Compton, and the ascent of directors like Ryan Coogler, Ava DuVernay, Lee Daniels, and Steve McQueen. Last year, movies with predominantly black casts spent five consecutive weeks at the top of the US box office in the crucial summer season. That’s not to mention the success of television shows such as Empire, Black-ish, Being Mary Jane, and the ShondaLand lineup. And all this in an industry that, despite ever-growing critical acclaim for black movies, continues to snub them at awards shows and that, despite an ever-growing roster of diverse black talent, fails to give them leading roles, or paints them purple, blue, and green when they get them, or would rather have Zoe Saldana wear a prosthetic nose than cast someone who looks like Nina Simone to play her in a biopic.

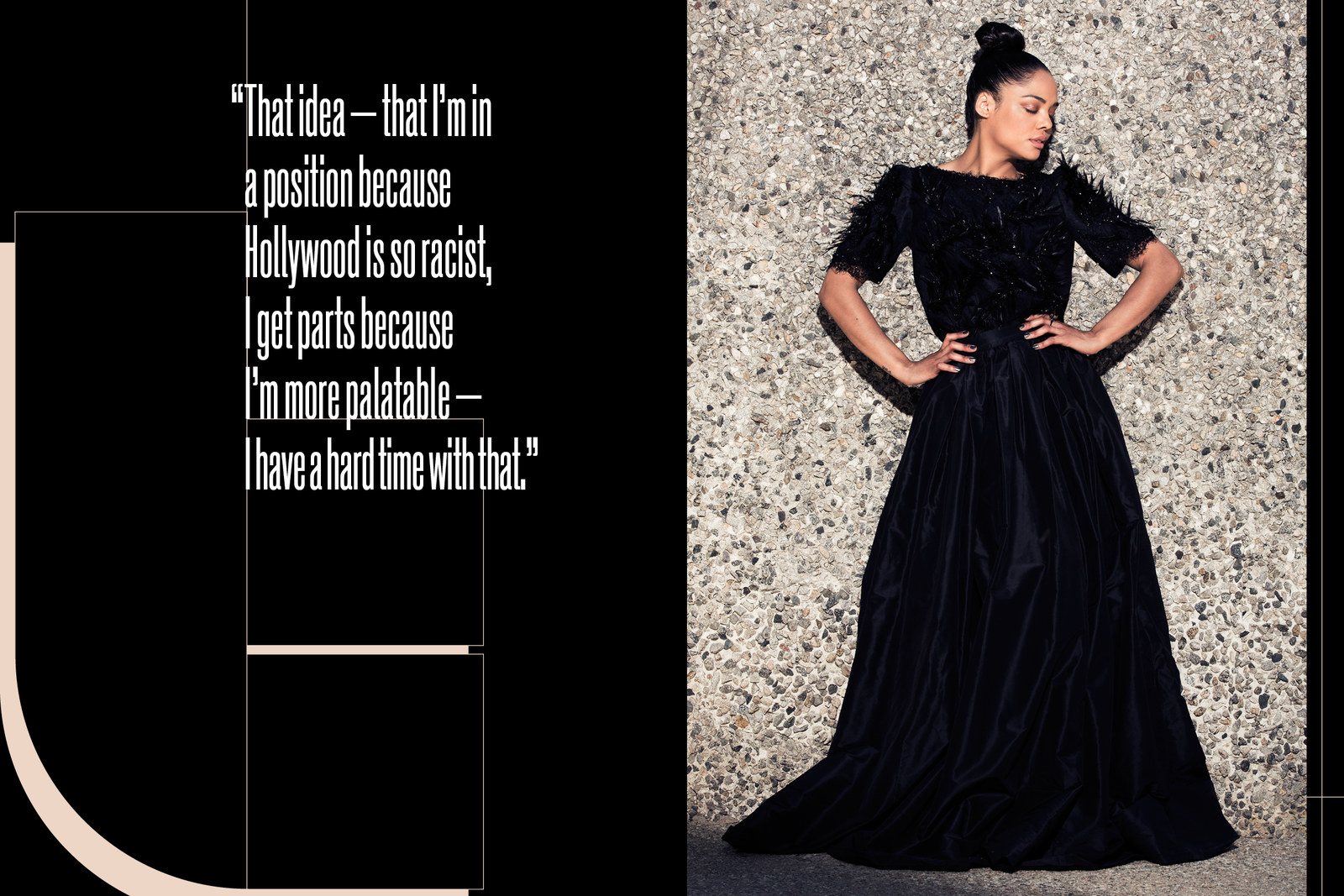

Thompson is caught in the crosshairs of this moment. After earning admiration for roles that were race-specific without being stereotypical, she is gearing up to be in three of Hollywood’s most highly anticipated sci-fi and fantasy franchises — notoriously white genres in which none of her characters were written to be racially defined. Her success is a symbol of both the industry’s attempts at progress as well as its limits. Thompson is a blessing at a moment when Hollywood can no longer ignore the lack of diversity in casting — for financial and PR reasons alike — yet still often favor light-skinned actors who satisfy Western beauty standards (if casting people of color at all). She’s the first to acknowledge her ascent may be the effect of a turning tide, not just the cause of one. But after over a decade of diligently building her résumé — and much longer being the kind of person who calls her high standards an impediment — that acknowledgment carries its own friction. How does she embody this pivotal cultural moment without being being defined by it?

“I remember reading some idea that I had been cast in Creed because I'm light-skinned," she says. "That idea — that I'm in a position because Hollywood is so racist, I get parts because I'm more palatable — it's not that I'm uncomfortable confronting the validity of that, it's that I also feel—” She stops and bites her lip. "I have a hard time with that. Because I just don't think it's true.”

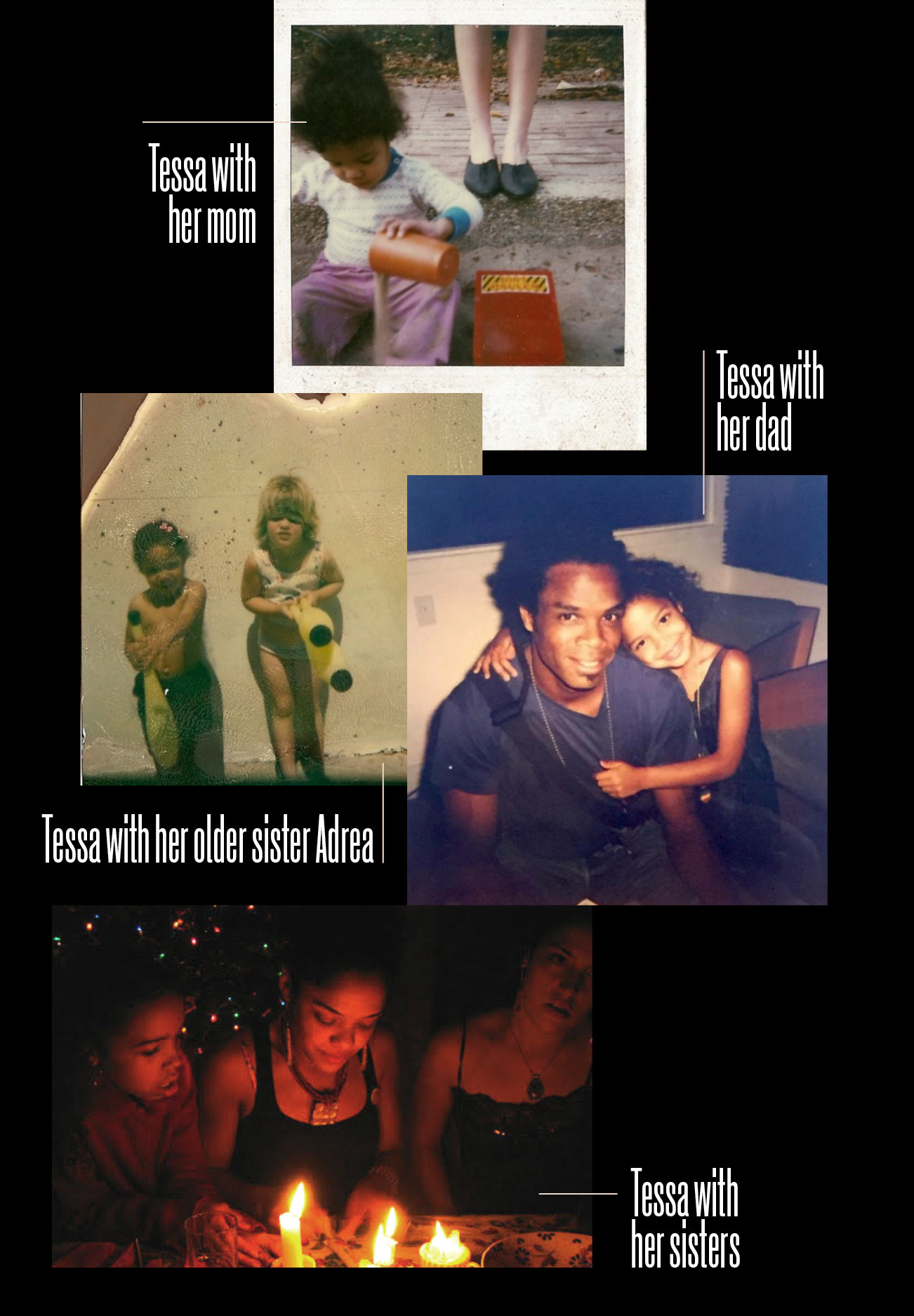

Having been raised by a black Panamanian father and half-Mexican, half-white mother, Thompson has spent her entire life probing the kinds of identity questions that confront so many of her characters. She was born in Los Angeles and spent her childhood shuttling between school in California, where her mother and older sister live, and holidays in Brooklyn, where her father, a musician, once lived with Thompson’s younger brother and sister and her stepmother. “My family's really open,” she says, cradling a cappuccino in the corner of the bar. “It wasn’t the sort of family environment where, ‘You're the kid, go to bed,’ or, ‘You're the kid, so you can't hear this part of this conversation.’”

As a child, she bounced from public elementary school to being homeschooled for a time by her mother — who, among having other jobs, worked in administration at UCLA — to attending alternative charter and private schools. Though she grew up without a television, she was fascinated by filmmaking, and once produced a homemade show with her dad about hunting for lizards in the Hollywood Hills. She left voicemails as different characters on her dad’s answering machine and, on at least one occasion, went to the park dressed in drag. “I stuffed all my hair into a baseball cap just for fun and I pretended to be a boy,” she remembers. “I've always been someone that's really fascinated by identity and really aware that it's a creation.”

It’s the type of bohemian, bicoastal upbringing one might expect of a budding performer, but it wasn’t free of obstacles. Thompson’s family paid nothing for her to attend private school in eighth grade, where she was, in her own words, there “to fill a quota”; and her thrifting habit, for which she’s received fawning fashion press, was born partially of necessity. “We were broke,” she says. “At the time it was horrifying because everyone's back-to-school shopping and you wanted the new things. It wasn't until later, once I had a knack for it and liked it, that it actually became sort of signature.”

Growing up in liberal locales also didn’t shield her from the realities of being multiracial in America. Thompson was around 7 when she was called a “nigger,” by a younger girl on a playground in suburban LA. She begged her mom to transfer her to the public Santa Monica High School after feeling trapped in private school. “I was one of four kids that were anything but white,” she says. Though the public school had 4,000 students and was incredibly diverse, it was also plagued by self-segregation, which she responded to by helping found a “racial harmony” club with older classmates her freshman year. “It was a weekend sleepover where 20 kids from each racial group would come together and dialogue over racial stereotypes,” Thompson explains. Her first year, she joined the club as a black student, the second as Latina. “I tried to do it my third year as a white person and they wouldn't let me,” she says, laughing.

“I've always been someone that's really fascinated by identity and really aware that it's a creation.”

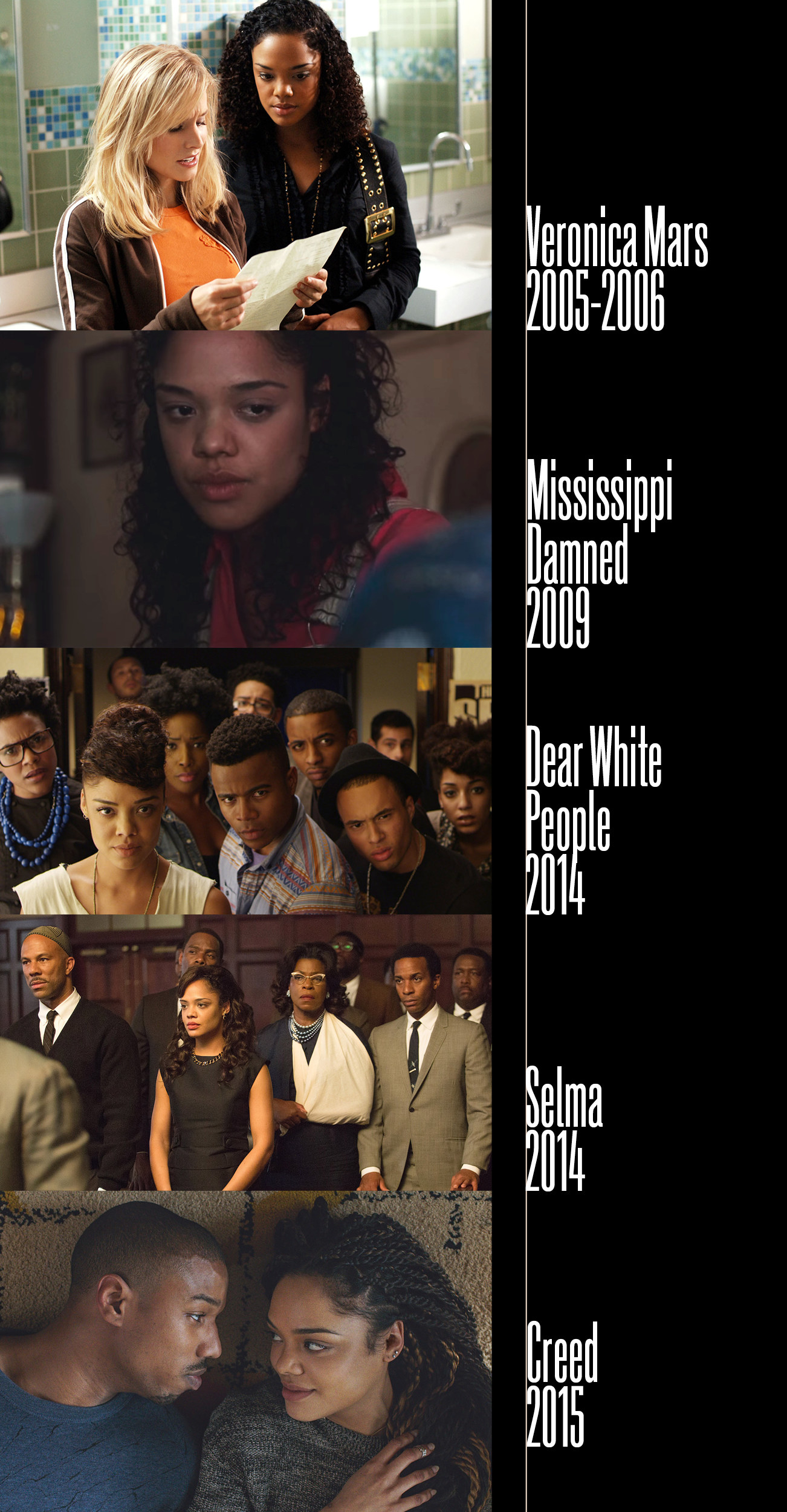

Thompson enrolled in community college with the intent of later joining the peace corps, but she quickly abandoned her plans to pursue acting. Her first paid role was in a 2003 theater production of Romeo and Juliet set in Antebellum New Orleans (the Capulets were Creole, the Montagues were American Protestants).

“Everything, even in the theater space, felt race-specific at the time in a way that I was sometimes the benefactor of in a great way,” Thompson says. “My counterpart as Romeo was a recent Juilliard grad, and I was completely untrained. But that happened because I looked the part and had a natural aptitude at Shakespeare and could be directed. So, in that case, I was lucky that they wanted a girl like me.”

Two years later, Thompson landed her first TV gig as a 1930s lesbian bootlegger in an episode of Cold Case. For the next near-decade, she picked up roles in dozens of television shows and movies, learning early on she had an affinity for characters whose race was central to the performance — whether she wanted it to be or not. On Season 2 of Veronica Mars, she played Jackie Cook, the title character's best friend's girlfriend, a role that was ultimately written off the show due to poor reception from fans. “Even on that show, a show that was so smart, I felt like my character was still boxed into a space of being the black girl,” she says.

It also wasn’t long before Thompson was forced to confront the palatability having light skin affords her as an actress of color. Following her feature film debut in 2008’s Make It Happen, a poorly reviewed dance drama, she co-starred in Tina Mabry’s Mississippi Damned, a markedly heavier movie that explores intergenerational trauma within a rural black family. It’s a film Thompson comes back to often — when discussing directors she admires, when lamenting the lack of distribution for black films — and one she’s clearly proud of. Thompson played, as she puts it, the “light of the movie,” an aspiring pianist who ultimately breaks her family’s cycle of addiction and abuse. However, she also recalls the moment a filmmaker at Slamdance — a festival for indie films and emerging artists — pointed out that there was something “rotten” in the movie. “It was the casting of me,” she says. Specifically, the filmmaker believed it was irresponsible to cast the lightest-skinned character in the movie as its heroine.

Though Thompson defends Mabry's decision on account of the fact that the movie was autobiographical, the interaction made her more conscientious of the implications her casting can have in films; one filmmaker later admitted to her that he was worried she was too light for a potential role, but that it could be “cool” because her character was indeed, again, "the light of the movie." "And I remember being like, ‘Oh, nope, not interested,’” she says. So, what did she think of Zoe Saldana being cast as Nina Simone?

Thompson considers the question, the cursive “yes” tattoo on her right outer wrist peeking out from the sleeve of her blouse. “I'm not sure she would have been the first person that I would have thought of to play Nina,” she says, her words measured. “To me, Nina is someone that was so seamless, she couldn't separate her politics from her work. She was an artist that said to us, 'How could you not reflect the times that we live in?' And that's not something that I've necessarily seen in Zoe's work in the same way.”

“I don't begrudge anyone that doesn't decide to make choices based on that, because I think the way that we move through the world has everything to do with what has been handed to us,” she continues. “I've been dealt a very different hand.”

It was Thompson’s role as Sam White, a tempestuous, biracial black rights activist at a fictional Ivy League university in Dear White People, that solidified her position as a go-to actress for roles that speak to the complexity of the black experience. A fast-paced satire, it features a diverse ensemble cast who deliver acerbic lines faster than you can recover from them. (Professor: “I read your entire 15-page unsolicited treatise on why The Gremlins is actually about suburban white fear of black culture.” Sam: “The Gremlins are loud, talk in slang, are addicted to fried chicken, and freak out when you get their hair wet.”) After having been sent two scripts for network dramas in which she would have played a slave, the film felt “like a beacon of hope.”

In the movie, Thompson is torn between her allegiance to the all-black house on campus and her relationship with a white teaching assistant. “It felt like Sam White was somebody that was manipulating identity and really understood that identity is a performance,” Thompson says. “I think because of my high school experience I understood what that was. And it was a way to get to process that and think about that with levity.”

Thompson followed Dear White People with a small but pivotal role in Ava DuVernay’s historical drama Selma as Diane Nash. Nash, a radical who co-founded the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, occupies as unique a space in the film as she did in history: one of a handful of female leaders who had MLK’s ear, and often the only one in rooms full of men. “I've spoken to people and I'll say that I was in Selma and they're like, 'Oh yeah? You were? Who did you play?'” she laughs. “I'm like, ‘Thanks. I was in Atlanta for three and a half months filming that movie!’”

Yet if her presence in Selma was muted, it was amplified in Creed, where her performance as Bianca, an aspiring singer with progressive hearing loss who lives downstairs from a boxing scion in training, was celebrated for offering so much more than the “thankless girlfriend roles” typically portrayed in blockbusters. In one particularly poignant scene, Adonis Creed helps Bianca take out her long Senegalese twists, a protective style worn by black women that fits with the film’s winter Philadelphia setting. “[It] is not necessarily a political movie, but the way that we had conversations, we thought we were making a really cinema verité about the black experience.”

All of Bianca’s songs in Creed were co-written by Thompson and Swedish composer Ludwig Göransson, and sung by Thompson herself. She used to perform in the indie electro-soul band Caught a Ghost before deciding to commit fully to acting, and says that music is the only other career she can see herself seriously pursuing.

“Maybe I'm romanticizing it, but I think there used to be this idea that you were a craftsman, that you had mastered something and that was enough,” she says. “It takes a while to get good at anything. Even for the people that appear to be overnight successes. Jennifer Lawrence had been acting since she was a kid. Lupita went to grad school for theater — she's not some bumpkin that came out of nowhere. Brie Larson has been around forever. All these ideas that this person falls out of the sky and gives a brilliant performance? Fine. But it doesn't generally happen that way.”

Thompson eyes a stack of cookbooks on the shelves towering beside us. She picks a copy of Entertaining With the Sopranos and smiles as she thumbs through recipes like “Carmela’s Lasagna.”

“I've never seen all of The Sopranos,” she admits. “It’s important, though, because it marked a real shift in television … Have you seen The Wire?” I shake my head in embarrassment. “Me neither,” she mouths. We discuss our wariness, given that watching the show has become the equivalent of saying “But I have a black friend.”

“People like to hang their hat on that. I know a couple of white people like that. I may or may not have been in a relationship with someone like that. I’m going to watch it someday. By the time I see you in Los Angeles, I will have watched all of The Wire.”

It’s a Saturday afternoon in April at the Getty Center, the sprawling art-filled complex of modern stone buildings perched atop Los Angeles in the Santa Monica Mountains, and Tessa Thompson still hasn't watched The Wire. She wants to see the Robert Mapplethorpe retrospective and walks into the center’s gleaming rotunda in a billowing white maxi dress that, despite the hard angles of her ankle boots, makes her look as if she’s gliding. “I love it because you can see the city," she says. "It's just sort of dreamy and you're above it."

Thompson is in town to shoot Westworld, the highly anticipated sci-fi Western that, after numerous delays, is finally set to premiere on HBO in the fall. In a week, she’ll fly to London to join Jennifer Jason Leigh, Natalie Portman, and Gina Rodriguez in shooting Annihilation, a sci-fi thriller adapted from Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach trilogy. And just days ago, it was announced that Thompson will join the Marvel Universe to play the female lead opposite Chris Hemsworth in the upcoming Thor: Ragnarok. After years of projects that were firmly grounded in reality, Thompson’s plunge into science fiction and fantasy did not come about by accident. “I was sort of like, I want to do something so far away from that, I want to go to another planet.”

As we make our way through the museum, we step out onto the balcony of its west pavilion, city and sea stretching before us like a living diorama. She plots points of interest: the Santa Monica Pier to the right, downtown LA to the left. Mid-City or Century City is directly in front of us, though she’s not sure which. “I’m sort of bad at this game,” she laughs. She walks up to the tall, handsome black man standing beside us and asks. It’s Century City. “I’m from LA. I should know that,” she tells him. “It’s very nice to meet you,” the man responds, beaming, while his gaze extends just over her shoulder. Thompson turns around to see a graying woman with a camcorder in hand filming excitedly. “My mom is so happy to actually see an actress while she's out here.”

Eleven years after her first television role, Thompson, who relishes people-watching on the subway and taking surreptitious photos of people she finds interesting, has a difficult time imagining the day — imminent as it is — that she can still consider herself not to be famous. “When we did the premiere of Creed, I found that experience overwhelming,” she says. “From the second I got out of the car, I was on camera because they're putting it up on a big screen and then everyone that's in the square can see. I'd never been a part of something like that. And in some ways it was better that I was unprepared because if I had known that that's what I was walking into, I might have been frightened.”

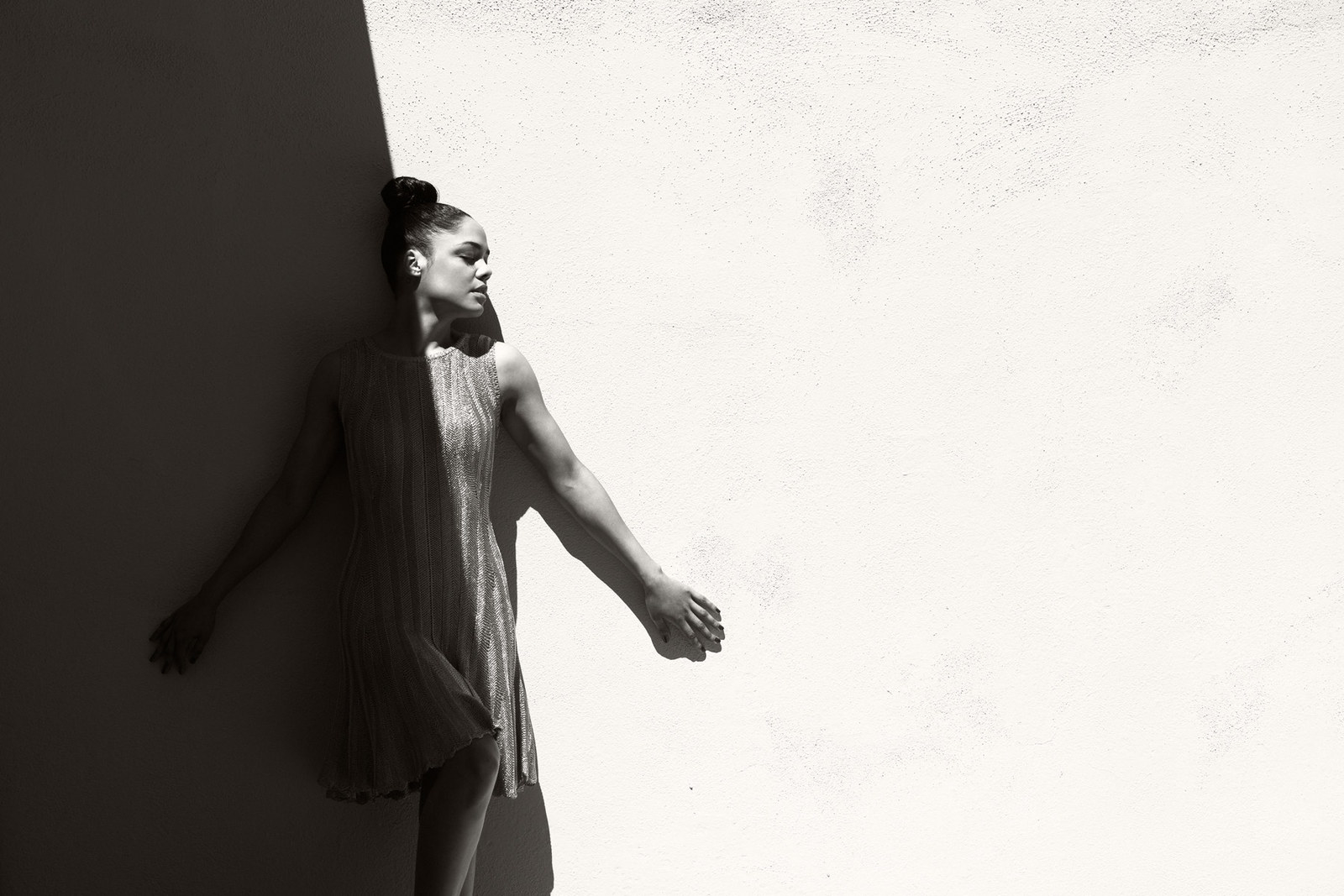

Having had no real relationship to Hollywood growing up, she flouts certain conventions the industry holds sacred. When Vogue crowned her Hollywood’s newest “It girl” in March, with a full-page photo of Thompson in a sleek, sequined Marc Jacobs gown at the London premiere of Creed, she posted a screenshot from the issue to Instagram and thanked the magazine for the shout-out. However, she also questioned the use of the term, which has dubious origins. “To me, seems easy enough to ‘have it’ when you are in sequins from head to toe and enough diamonds to warrant security in case you make a run for it,” she wrote in the caption. But she is wary of being too revealing.

“If you have social media at all as a public figure, there's sort of this expectation that you're an open book, and I'm just not interested in engaging in that way,” she says. Her Instagram feed, on which she posts to her 135,000 followers a few times a week, does offer some glimpses into her personal life: friends like Janelle Monáe and indie musician Moses Sumney; idols like Eartha Kitt and Prince. Recently, she also posted photos of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile as well as the Black Lives Matter protests that have come in the wake of their deaths, and replaced her bio with links to the GoFundMe pages for the families of both men. “There's no way I could ever be dismissive of what you can do on social media. I like people that have real direct conversations with their fans. I'm interested in watching that from afar. But personally, that's not a thing that I want. I don’t think I’d be good at it."

While Thompson was invited this year to join the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, she isn’t precious about awards and has cited the fanfare around them as her Hollywood “pet peeve.” Of the most egregious examples of movies with majority black casts and black directors that have been snubbed in recent years, Thompson has been in two of them: Selma — which won for Best Original Score, but lost Best Picture, and for which neither Ava DuVernay nor David Oyelowo received nominations — and Creed, which earned only one supporting actor nod for Sylvester Stallone. “Both with Selma and with Creed, the conversation becomes, 'Oh, you were snubbed.' No, we weren't. We did so well. We made a film that we're proud of and that did incredible things.”

“I'd like to think some of it is not just racism, it's people wanting to see what has been in their imagination. And then of course some of it is just racism.”

However, she also recognizes the deep significance awards can carry as acknowledgment of black artists and black art. In 2014, the year Lupita Nyong’o won Best Supporting Actress, Thompson attended the annual Oscar-watching party hosted by DuVernay in LA’s Downtown Independent theater. “To be in a room with other filmmakers and a lot of black people — just the feeling in that room,” she recalls. “There was a symbolism there that was so ripe.”

As we enter the Mapplethorpe exhibit, Thompson explains that she became fascinated with his work — which is best known for its provocative depictions of homoeroticism and S&M — after reading Just Kids, Patti Smith’s memoir of her and Mapplethorpe’s boundary-breaking relationship. “I was very enamored with their reversal of gender roles and how they continued to be friends and supporters of each other, even when it was clear he was gay,” she says.

She pauses at “Ken and Lydia and Tyler,” a nude photo, presented from the neck down, of a woman poised between two men, the three of them ordered from left to right by skin tone. “On Westworld, there are sometimes scenes with a lot of naked bodies,” she says. “I shot one of my first ones the other day and I was so distracted. It's just a room of 200 naked bodies and I just wanted to look at every single inch of every single one of them.”

Thompson is keenly aware that her foray into sci-fi projects like Westworld is more than just a boon to her range as an actor, not to mention her career and tax bracket. She recalls a conversation she once had with Justin Simien, who directed Dear White People. “We were joking and he was like, 'How come there are no black people in the future?’" she laughs.

Months ago, Thompson and her older sister were watching an action film set in the future — maybe Prometheus, though she’s not certain. “My sister’s like, ‘I'd love to see you in one of those movies,’” Thompson says. “I remember laughing at the time, just because I could never see myself in a movie like that. But I realize it has to do with the fact that well, yeah, it doesn't happen a lot. Growing up, as a little girl, I would not have seen myself in a movie like that.”

Now Thompson is not only going to be in one movie “like that,” but in two movies and a prestige television show. Though her character in Annihilation has yet to be confirmed, if characters are to match those in the book (which, Thompson reveals with a sly smile, they may not), she’ll likely be playing an anthropologist or a surveyor — professions historically dominated by white men.

Perhaps nowhere is that weight more palpable than in the reaction to the announcement that Thompson will play Valkyrie, a Norse warrior goddess, in Thor: Ragnarok. Marvel has been lauded in the past year for its decisions regarding Black Panther — Coogler will direct the upcoming movie starring Chadwick Boseman and Ta-Nehisi Coates is writing the latest installment of the comics — and recently passed the Iron Man mantle from Tony Stark to a black teenager named Riri Williams. However, there isn’t a single black woman on Marvel’s staff to write Riri. Marvel’s decision to cast Tilda Swinton as the Ancient One, a traditionally Tibetan character, in the upcoming Doctor Strange film, has also been roundly lambasted. According to an exhaustive breakdown from Nerds of Color, in Phase One of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, which covers the studio’s six releases from 2008 to 2012, of 61 top billed characters, only 10 were people of color, and only one was a woman of color. Thus many fans, who’ve long lobbied for more diversity among superheroes both in print and onscreen, are thrilled to see Thompson play Valkyrie, who, in the comics, is prototypically white and blonde.

“Right from the start we wanted to diversify the cast, and it’s hard when you’re working with Vikings,” Thor: Ragnarok director Taika Waititi recently told Comic Book Resources. “You have to look at the source material as a very loose inspiration … What do we even care?” he said. “We cast a very broad net, and Tess was the best person.”

Of course, many comic fans care. “I think it's disgusting they casted FOR diversity,” remarked one commenter on the interview. “If it's all fine and good to ‘diversify’ Norse gods, why is [it] totally unacceptable to cast white actors as Egyptian gods?” wrote another. Thompson, who has promised herself she would not look at comments regarding her casting, tries to stay empathetic. “So many of those comics were written a while ago, when there weren't as many conversations about inclusion or diversity,” she says. “I'd like to think some of it is not just racism, it's people wanting to see what has been in their imagination and what they've seen visual depictions of...and then of course some of it is just racism.”

Thompson stops in front of a collotype of Josephine Baker, eyeing the tendrils of Baker’s hair delicately sculpted into the signature curve on her forehead.

“It’s so incredible when someone comes along who does baby hair, like FKA Twigs, but her fans don’t know about Josephine Baker,” she muses. “I used to do that shellacking of the baby hair before it was, like, alt. It was just, at that point, considered hood. I just always thought it was so beautiful.”

As we exit the museum and wait in line for the tram to take us down to the parking deck, Thompson explains that despite the undeniable significance of her impending roles, that weighed less on her mind when she chose to take them. “It's not a political thing for me — it just seems really fun to work in that space,” she says, noting her excitement to work in front of a green screen. “Everything is imagination and I've never done anything like that.”

It reminded me of something Thompson had told me when we first met in Manhattan. In December, she had sat on a panel with Coogler, actor Andre Holland, and R&B musician Ledisi as part of Array Now, a black film festival founded by DuVernay. They were discussing Paris Blues, an early-’60s film in which Paul Newman and Sidney Poitier play two expat jazz artists who fall in love with two American women played by Joanne Woodward and Diahann Carroll.

“In every conversation, it always goes back to race because Diahann Carroll's character is basically saying to Sidney, ‘What about black people back home? You're here in Paris and you're this expat but what about us, what about the real work?'” Thompson had said. “It's an incredible film … But also, you're like, can we just have fun?” She growled playfully. “Can't they just for once be talking about something else? And I guess that's the sensation [I have] sometimes.”

In that moment, I felt guilty. Thompson and I had spent hours talking, and though we discussed topics as random as her most recent dream (“These cats were trying to invade my house and it sort of got violent — I cut a tail off”), our conversations inevitably turned back to race in one way or another. As a biracial journalist, I’m all too familiar with what it’s like to be asked to answer for a notoriously white industry — it is exhausting.

“But maybe not,” she continued. “Because, in the end, they're the relationship that matters in the movie. They're the ones that give it its heart and resonance. And I also think the conversation is shifting. Even in the years I've been working and making movies it's shifted so wildly that I'm like, I hope to work another tons more decades so it will continue to do that. And the idea that in any small way I'm part of the conversation shifting and opportunities changing for people is so cool. So in that way, I'm happy to talk about it until I'm blue in the face.”

“In the hope of one day not having to?”

She let out a long, resigned sigh. “Yeah, absolutely. You talk about it enough so you never have to talk about it again.” •