An Aboriginal man who has been locked up for a quarter of a century for a murder he says he did not commit says police held a gun to his head and threatened to “dispose” of him off the top of a mountain if he did not confess to the crime.

The confession is the only piece of evidence that ties Kevin Henry, who was 21 at the time, to the murder of an Aboriginal woman in the Central Queensland town of Rockhampton in 1991. Lynda, whose surname has been suppressed out of respect for her family, was found on the banks of the Fitzroy River on September 1 of that year.

Henry was convicted of her murder in 1992. But he has continued to protest his innocence since then, and there has never been any DNA or forensic evidence linking him to her death.

Henry, now 48, is currently serving time over his sentence, and has been continually refused parole, partly due to his refusal to admit guilt.

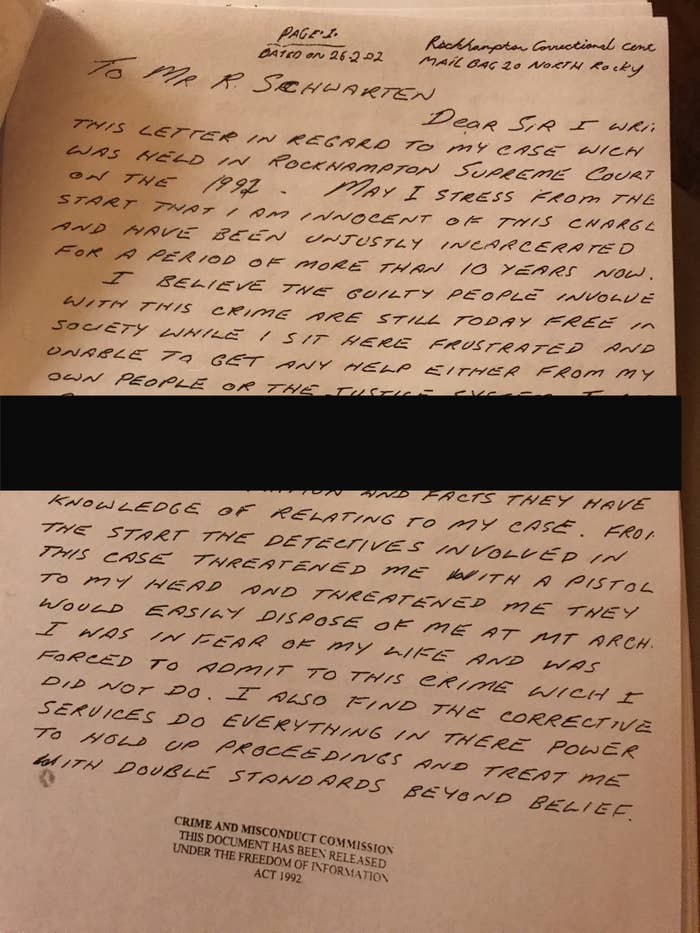

In 2002, Henry wrote a letter to his local Labor MP Robert Schwarten, then the state’s public works minister, stating he had been “unjustly incarcerated” by investigating officers, who he claimed had threatened him at gunpoint if he did not confess.

BuzzFeed News has obtained a copy of this letter.

“From the start, the detectives involved in this case threatened me with a pistol to my head and threatened me they would easily dispose of me at Mt Arch (sic),” Henry wrote in the letter.

Mt Archer is the highest mountain in the Berserker Range, which circles Rockhampton’s north side.

Schwarten forwarded Henry’s allegations to the Crime and Misconduct Commission (CMC). The body was established to investigate crime and corruption in the public sector, including in the police service.

It was not the first time Henry had made allegations to the body. Henry had made his first complaint to the Criminal Justice Commission (CJC) in 1993, and then in 1999. The CMC was set up following the merging of the CJC with the Queensland Crime Commission in 2001. It is currently the Crime and Corruption Commission (CCC).

In 1993, Henry claimed he had been wrongfully convicted and alleged police officers in the case had taken false witness statements while witnesses were intoxicated.

The CJC decided not to investigate any further in 1993, stating the “commission could not act as a further appeal forum”. In 1999, it again said it could not work as an “appellant court”.

Henry has exhausted the appeal process but his legal advocates say his appeal was not based on the new information that has since come to hand.

In 2002, at the time of Henry’s third complaint, the CMC referred the investigation to the QPS.

The QPS investigation was conducted by a detective acting senior sergeant, who cleared the investigating detective of the allegations, stating he found “no evidence of misconduct or breach of discipline”. At the time, the detective investigating Henry’s complaint, was stationed at the Rockhampton local area command, along with the detective alleged to have put a gun to Henry’s head.

In response to the QPS investigation, the Crime and Misconduct Commission wrote to Henry and said it "had no further requirements of the Police Service in relation to this matter".

But senior advocate for the Foreign Prisoners Support Service Martin Hodgson says the matter was a case of “police investigating police”, and that there is reason to believe Henry’s confession was coerced.

Over the past year, a renewed investigation into the case by Hodgson has also cast doubt on his guilt, based on historical tidal records, new forensic analysis, Henry’s alibi, and three witness statements that point to other perpetrators, that were not taken into account.

In 1991, Lynda was found murdered on the banks of the Fitzroy River, which runs through the centre of Rockhampton.

Lynda was from South Australia, and had been missing for eight days before her death. Her non-Indigenous husband, who she was separated from, lived in the town with their four sons.

Educated and accomplished, Lynda had been at the forefront of early childhood education in South Australia, helping set up the state’s first Aboriginal pre-pre school in the 1970s. At the time of her death, she was being treated for schizophrenia.

Lynda had come from a strong Aboriginal family in her home state, but had not escaped trauma. Seven years before her death her brother had died in custody, and had become one of the most high profile cases investigated by the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. The report was handed down only a few months before Lynda’s death.

Within a week of her death, four people had been charged over her murder — three women and Henry — related to two separate sets of circumstances: three women for brutally assaulting Lynda; and Henry for allegedly placing Lynda in the river. The women later had their charges of murder downgraded to grievous bodily harm and were convicted of these charges.

The assault was witnessed by up to 35 people who were at Toonooba House, a local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander alcohol and drug rehabilitation centre, run by an Anglican church charity.

The building was on the banks of the Fitzroy River, and was known as a sanctuary for Aboriginal people, with many of them sleeping underneath the house on mattresses during the night.

On the night of August 31, 1991, it was not a sanctuary for Lynda. The assault was perpetrated over a period of more than an hour, and Lynda sustained horrific injuries. She suffered severe trauma and bleeding to her head, body and perineum. It is likely she could have died of these injuries.

There is no suggestion that Henry was involved in the assault. Instead, police allege that after the assault he dragged Lynda to a nearby clearing, where he sexually assaulted her then placed her in the river where she drowned.

There were no witnesses, and new analysis of historic tidal records by Hodgson, as well as analysis of the forensics in the case by international experts — which state she may not have died by drowning — cast doubt on this version of events.

Henry was visiting Rockhampton that weekend from his home in the Aboriginal community of Woorabinda, a two-hour drive away.

Not only did Henry have an alibi — he was drinking at a local pub with a group of Aboriginal people from Toonooba House — he didn’t have any of Lynda’s blood or DNA, or river mud, on his clothes.

Instead, Henry’s conviction was reliant on a confession three days after Lynda was found in the river. Henry was picked up off the street in Rockhampton, and taken to the watchhouse where he was questioned by two detectives for two and a half hours, during the course of which he confessed.

The judge at Henry’s trial threw out a large portion of the confession, stating it was not admissible as a “voluntary statement”; that a large portion of the statement was “tainted”; and that police had “ignored” Henry’s right to silence.

“Clearly enough, the accused is exercising his right to decline to answer any further questions,” the judge said at trial. “The exercise of this right is ignored by the investigating police, and the accused is put in the position where he is effectively told he has no such rights.

Despite this, Henry was convicted of the rape and murder and was handed a life sentence, which in Queensland meant 25 years.

Hodgson, who has worked on wrongful conviction cases for a decade in the United States, including the death penalty case of Rodney Reed, believes Henry’s confession was false, and says the fact the trial judge threw out a large portion of it is significant.

Hodgson says Henry has repeatedly stuck to his story that officers put a gun to his head, and threatened to take him up to Mt Archer. He says despite Henry making the allegation, the CMC refused to investigate, and the Queensland Police cleared itself of any wrongdoing.

He says Henry did not have legal representation during his multiple police interviews, and he was likely still intoxicated. He had only reached Year 9 at school and was illiterate at the time, and the tape was stopped three times during the course of the interview.

Henry’s cousin Doug Graham saw footage of the alleged confession shortly after Henry was detained. He said Henry seemed "drowsy from sleep”, or looked intoxicated.

"After police stopped the tape during the interview where the alleged confession was offered up, Henry changed his statement dramatically," Hodgson told BuzzFeed News.

"There's clearly multiple windows of opportunity for police to have done something to force a confession.

"There are questions that need answering about what happened every time that tape was turned off. Clearly the trial judge shared my concerns, he stated large parts of the statement were 'tainted and cannot be received as voluntary'."

Hodgson says the judge allowed in a portion of the statement before Henry makes it clear he wanted to terminate the interview. In that portion, Henry does not admit to murdering Lynda.

He says the matter deserves to be fully investigated.

"Kevin's allegations were investigated by a member of the Rockhampton police, at a time when the detective alleged to have used the gun against Henry was still a member of the Rockhampton local command. We have to raise questions about the practice of police investigating police, and ask the CMC why they refused to investigate further, or at least provide real oversight.

"This supposed confession is the only piece of evidence against a man who is still behind bars 26 years later."

Hodgson says cases of false confession are prevalent in the United States, but that Australians find it hard to believe you could confess to a crime you did not commit.

“Kevin’s case has similarities to many cases of false confession in the US. We now have popular culture delving into the problem of false confessions, from Making a Murderer to The Confession Tapes, but in Australia, we still refuse to believe someone could be made to confess to a crime they did not and would not commit.

“But if it can happen in the US, it can happen here. This was after all when Queensland had just been through the Fitzgerald Inquiry.”

The Fitzgerald Inquiry, which uncovered the extent of police and political corruption in Queensland, was a watershed moment in the state, leading to the jailing of three former ministers and the resignation of former state premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen, who was later charged with perjury for evidence he gave to the inquiry. It was tabled in 1989, two years before Henry was picked up for murder.

In the US, one in four people who are exonerated by DNA evidence had made a false confession, according to the Innocence Project.

Hodgson says the fact Henry has consistently made this allegation over 25 years gives it credibility, as well as three witness statements that absolve him of the crime.

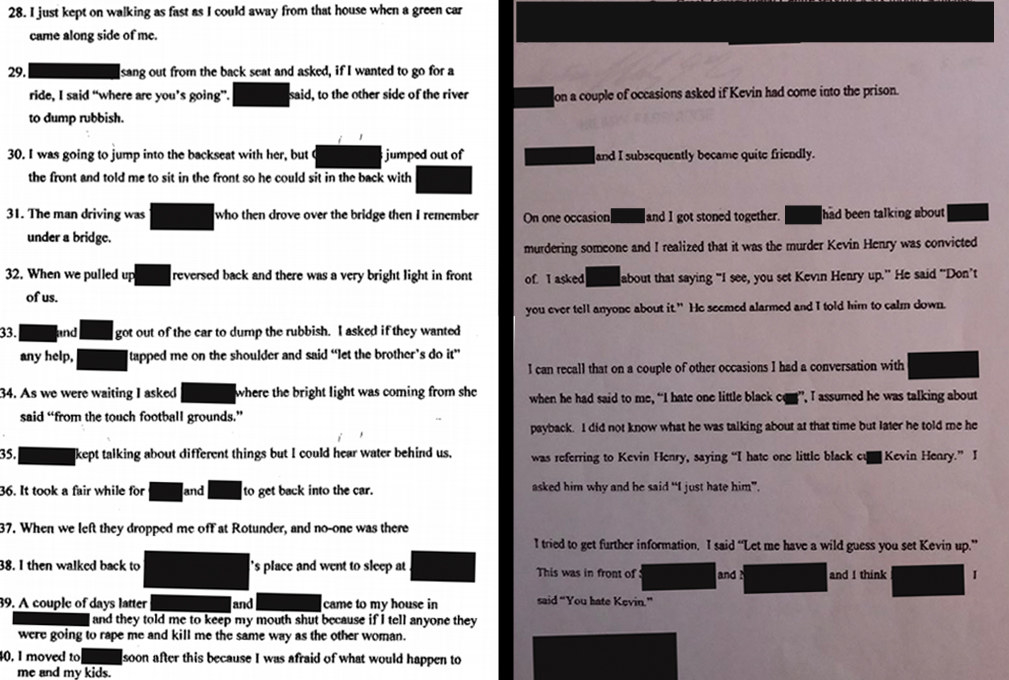

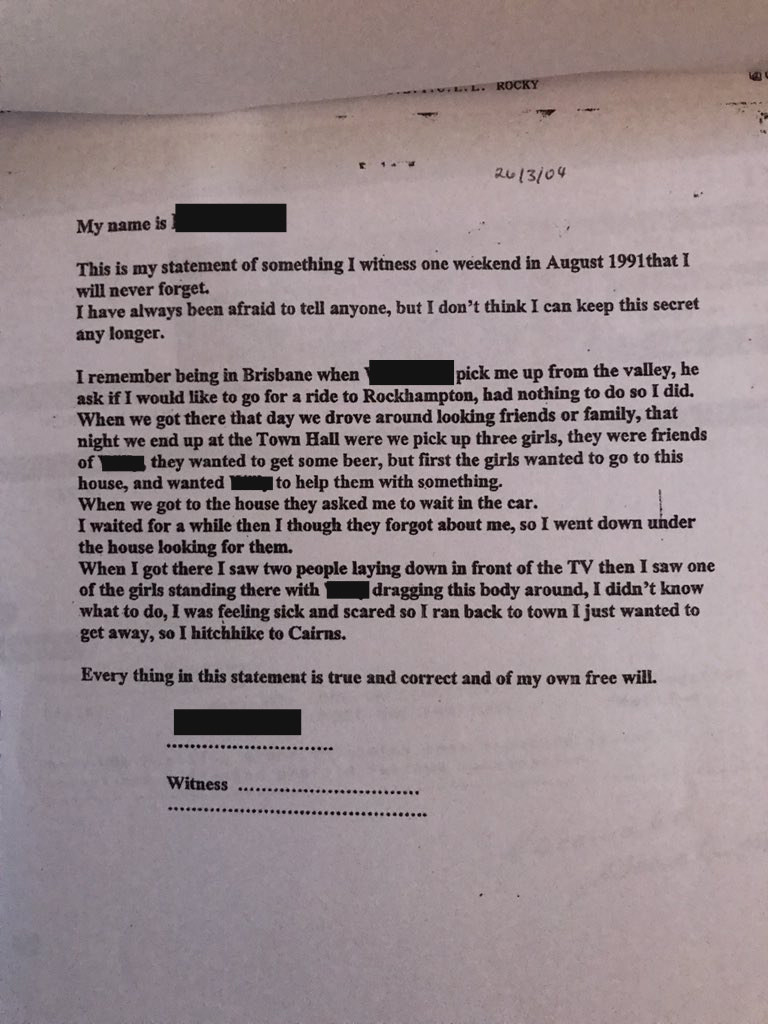

BuzzFeed News has seen copies of the witness statements.

Hodgson’s own investigation into this case has spanned nearly two years, and he says the evidence points to Henry’s innocence.

“We’ve uncovered three witness statements — one of which involves a woman who saw the real perpetrators put Lynda’s body in the river. Her statement is backed up by two other witness statements.

“But after the police had extracted a confession from Kevin, all other avenues of investigation stopped. They did not follow up any other leads, and instead tried to a build a case against Kevin.

“But there is no DNA evidence, or other forensic evidence linking him to the crime, he had an alibi, there’s no witness that saw Kevin commit the act and the events police allege do not align with where Lynda was found, on the other side of the river, or the forensic analysis of the crime.”

The Queensland Police Service told BuzzFeed News it "considers this investigation finalised and there are no current plans to reopen the case."

A spokesperson for the CCC told Buzzfeed News that the CMC was “satisfied with the manner in which the QPS investigated the complaint from Mr Henry.”

In relation to the issue of police investigating police, the CCC spokesperson said under the CMC’s governing legislation - the Crime and Misconduct Act 2001 - that “alleged corruption in an agency should generally happen in the agency”.

“If Mr Henry has any fresh evidence, or new information that he has not previously provided to the (Ethical Services Command) or the CCC, he can provide this to the CCC. The CCC would assess such information in line with our current complaints process.”

Amy McQuire and Martin Hodgson co-host Curtain The Podcast, a long-running investigation into Kevin Henry’s incarceration.