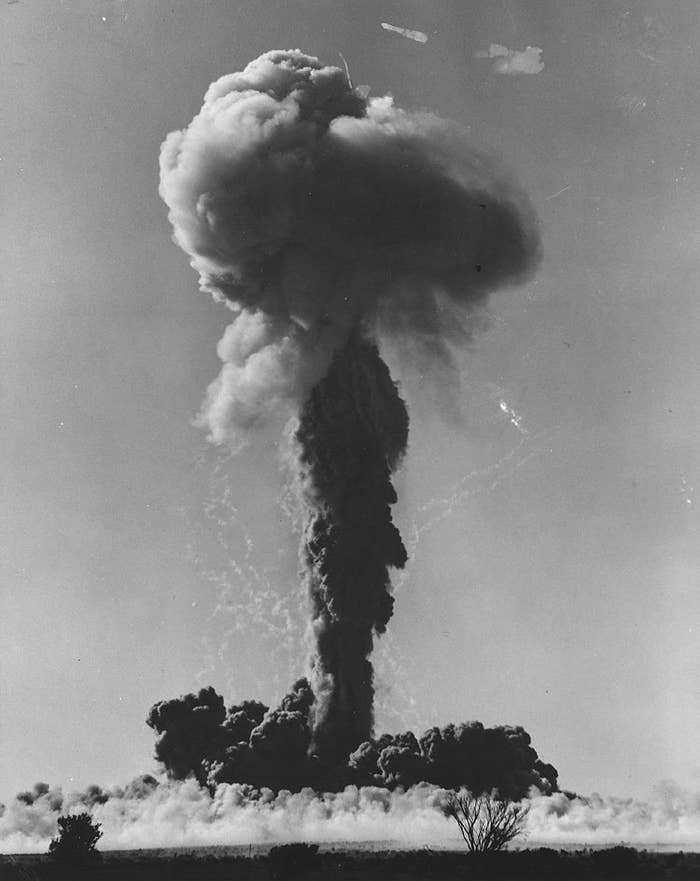

Sixty years ago, a black mist engulfed the traditional lands of the Yankunytjatjara in South Australia, leaving behind sickness not only in the bodies of the people and their children, but also deep within their country.

From 1952 to 1963, Australia allowed the British government to undertake a series of nuclear tests in Emu Field and Maralinga in South Australia, and the Montebello Islands off the coast of Western Australia.

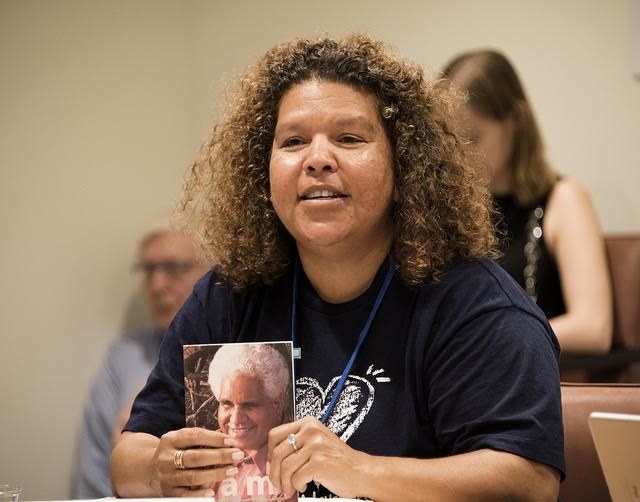

Karina Lester’s father Yami was only a child when the British government detonated the first of two nuclear bombs in Emu Field.

“Dad always remembers that it was black and silent,” Karina told BuzzFeed News.

“It rolled towards us without a sound. Usually you know if there is a dust storm coming so you can get shelter, but this black mist snuck up on everybody and no one could work out what it was. There was a lot of fear.”

Then people became ill. They suffered skin infections and sore eyes, including Yami Lester, who went blind shortly after.

Dr Elizabeth Tynan, author of Atomic Thunder: The Maralinga Story, told BuzzFeed News the “layers of secrecy” around the trials meant there is no official death toll or information on the number of people injured, although “we can be sure it was a lot”.

After a lifetime watching her father battle both Australia and British governments for justice, resulting in a royal commission in the 1980s, Karina took her people’s fight to the United Nations last month to speak in support of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which was formally adopted in New York over the weekend.

The treaty is seen as a vital step towards eliminating nuclear weapons, putting them on the same legal footing as chemical and biological weapons. It was adopted with a final vote of 122-1, with the Netherlands voting against and Singapore abstaining.

The treaty also recognises the disproportionate impact of nuclear weapons on Indigenous peoples around the world, and has provisions for assistance and reparations for those affected.

Despite its stated commitment to a nuclear-free world, Australia chose not to attend the treaty negotiations, along with all nuclear states: the United States, Britain, Russia, China, Pakistan, India, and Israel.

A spokesperson for the Department of Foreign Affairs told Fairfax in March that Australia was committed to eliminating nuclear weapons “in an effective, determined and pragmatic way”. A treaty without the participation of nuclear-armed states would not help that goal, the spokesperson said.

But the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons' Gem Romuld said Australia’s position was not justifiable “when we know how deeply devastating these weapons are, and with 15,000 of them still in the world”.

“The only way we can prevent them being used is to eliminate them, and the ban treaty is a very important step on the path to total elimination,” Romuld told BuzzFeed News.

Australia’s stance is also disappointing because of the impact of nuclear testing on Aboriginal people, she said.

“The whole campaign for the treaty has focused around the real world impacts of the weapon and what it does to people and the environment. Indigenous people have born the brunt of the impact, of not only nuclear weapons testing, but also the nuclear industry as a whole, from where uranium is mined, to the testing of bombs in South Australia and Western Australia,” Romuld said.

Not only did Aboriginal people near Maralinga and Emu Field suffer health problems following the nuclear tests, but they were also left dispossessed of their traditional lands. Many still fear it is unsafe to traverse their country despite clean-up efforts.

At the time of the nuclear tests, no one warned the local Aboriginal communities who had lived on their lands for tens of thousands of years. Many continued to walk their country, and continued to access their important sites and ceremonial grounds.

“Aboriginal people had no political voice at all, they had no say in what happened to them on these lands, and the British were not attuned to these issues,” Tynan said.

“The Australian government made sort of token attempts … but I don’t want to say to ‘look after’ (Aboriginal people), because they weren’t looking out for them at all.”

Tynan said Australia does not have an “honourable record” on issues like this, with the nuclear tests at Maralinga only stopped because of the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in 1963. “Australia really played no part in stopping testing on its own soil,” she said.

Although Australia has never been a nuclear nation, it is in a “unique position” because “we willingly allowed another nuclear nation to test weapons on our territory”, Tynan added.

“It just shows that at the time of the Maralinga tests we were a rather immature democracy more interested in kowtowing to a great power, and of course that great power happened to be the colonising power as well."

Romuld pointed out that the nations who did take part were former colonies of the nations who boycotted.

“Often people say, ‘oh, what’s the point’, because none of the nuclear weapon’s states have signed up, but I think that’s where they don’t understand … that it’s a tool to be used to increase pressure on states to reject nuclear weapons and disarm,” Romuld said.

“Most of the governments are from the global south, are from Africa and Asia and Latin America, and while they don’t have weapons and can’t disarm themselves, they have undertaken to do something which is in their reach, and that is to make this weapon illegal.

“There are a lot of countries who are former colonies of the nuclear weapon states, so I think that’s poetic justice in the stance that they’ve taken to declare the weapons of their former colonisers illegal.”

Australia’s refusal to take part in negotiations will remain a source of disappointment for Karina Lester, whose family still deals with the fallout of that black mist more than 60 years ago.

“It’s really frustrating when you know what happened in your backyard, you know how it impacted on Aboriginal people and your community, and your people," she said. "And then Australia not being there at the table to negotiate a treaty to ban nuclear weapons… It’s extremely disappointing.

“It’s almost gutting that the country that you live in, and the country where these nuclear tests took place, is not representing those people. It really shows where Aboriginal people are at a political level. We are at a very low end of the scale.”