TULSA, Oklahoma — One hundred years ago, Standpipe Hill in the Greenwood district of Tulsa was a battleground for one of the fiercest fights in the onslaught that is now known as the 1921 Tulsa race massacre. It was here where nearly 50 National Guard soldiers traded fire with a handful of armed Black men trying to protect their beloved and prosperous neighborhood from the violence and destruction of a white crowd. In the decades since, Black children in north Tulsa have been told not to play on what’s become known to locals as the “valley of the dry bones.”

On Monday, hundreds of flowers decorated the hillside as survivors, descendants, and locals honored those killed, particularly the victims whose identities remain unknown and whose bodies were never recovered.

“These bones have been speaking out for a long time,” said Kristi Williams, chair of the Greater Tulsa African American Affairs Commission.

Two of the three living survivors of the massacre — Viola Fletcher, 107, and her younger brother Hughes Van Ellis, 100 — were in attendance. Local musicians sang, drummed, and danced, while the crowd was asked to pick up soil, a tangible piece of history, and place it in jars to remember the dead.

“It’s emotional, but it’s really a celebration,” Janice Reed, a 35-year-old hairstylist born and raised in Tulsa, told BuzzFeed News. Reed said she’d been attending multiple centennial events to better educate herself about the massacre and what it meant for Black people in Tulsa.

“We can’t let the past drag us along; we have to take those steps to move forward,” she said. “What are the next things we do to unify and keep each other strong?”

For many, the answer is reparations, which survivors and their descendants have been demanding for years.

With the three remaining survivors all over 100 years old, the immediate need for reparations was obvious to many in attendance Monday morning. “Having that experience, that tragedy, that memory, and just wanting them to have some kind of peace,” said LaBrenda Washington Hutchinson, 35, who is from Tulsa.

While many in the crowd were Black Tulsans, either descendants of the massacre victims or people whose families have lived with its ramifications for years, other attendees had traveled to the city to bear witness.

“We can only get one 100-year celebration in a lifetime,” said Lashadion Shemwell, 34, who’d traveled to Tulsa for the first time from Houston with his mother, aunt, uncle, fiancé, and six children. “It was important for us to bring our children and be a part of it and just learn this history, because history repeats itself.”

The family was dressed in white T-shirts that read, “Black Wall Street — Never Forget 05/31/1921, Tulsa, Oklahoma.” His youngest daughter, 3-year-old Jurnee, met and spoke at the event with Mother Fletcher, the oldest survivor.

“To be able to pass on that generational resiliency and have it go from one generation to the next and be part of that,” said Shemwell, “it’s heartwarming and heartbreaking to remember all that took place here 100 years ago.”

On May 31, 1921, a crowd of white people, supported by local authorities, began a massacre that destroyed Tulsa’s Greenwood district, then one of the country’s most thriving Black communities and known as Black Wall Street. The mob had been incited by a newspaper editorial calling for the lynching of a Black man accused, with little evidence, of assaulting a white woman.

Over two days, the mob destroyed roughly 1,500 homes and burned at least 60 successful Black-owned businesses. Airplanes flew overhead, shooting at those fleeing and dropping bombs on buildings. Pictures of the aftermath show scorched trees, entire structures razed to rubble, and Black bodies lying in the streets of Tulsa.

Up to 300 Black people are estimated to have been killed during the Tulsa massacre. (In 2020, a city initiative uncovered a mass grave suspected to contain the remains of victims of the massacre.) Thousands were left homeless. Many fled Tulsa altogether, never to return.

The scars remain.

“I still see Black men being shot and Black bodies lying in the street,” said Viola Fletcher, who, at 107, is the oldest remaining survivor of the massacre, at a congressional hearing earlier this month. “I still smell smoke and see fire. I still see Black businesses being burned. I still hear airplanes flying overhead. I hear the screams. I live through the massacre every day.”

There were no arrests or trials. No one was ever held accountable for the deaths and destruction. Meanwhile, Black Tulsa was left to recover on its own. Insurance companies refused to cover the damage by falsely labeling the onslaught on Greenwood a riot incited by the city’s Black residents. And despite local and state officials' own role in the attack, the government never paid reparations to make the city’s Black community whole. Today, members of the Black community in Tulsa lag far behind their white peers economically.

Before the attack, Greenwood was home to thriving Black businesses and proud Black homeowners. Today, African Americans make up more than 15% of Tulsa’s population but are just 5% of the city’s small business owners. Black Tulsans are also far less likely than the city’s white population to own their homes.

“When I think about Black residents of Tulsa today, I wonder how different their lives would have been if they inherited the house that their grandparents built instead of being descended from people who had to relocate to a tent and start all over,” said Charlene Polite Corley, vice president of diverse insights and partnerships at Nielsen, the research firm that crunched the numbers on the massacre’s financial consequences. “The folks impacted by this are still here. Their family members are still here, and what they would have inherited was not just destroyed, but their stories were silenced.”

For years, the massacre was barely spoken about — not addressed by officials or acknowledged in history books. Starting just days after the massacre, officials in Tulsa, concerned about the reputation of the city, got to work covering up the true scale of the violence targeted at the city’s Black community.

It wasn’t until the 1990s that historians and media began uncovering this history, spurred in part by the search for suspected mass graves. The state of Oklahoma formed a commission to examine the massacre, with a 2001 report declaring it the worst civil disturbance in the US since the Civil War and a “tragic, infamous moment in Oklahoma and the nation’s history.”

“In the aftermath of the death and destruction, the people of our state suffered from a fatigue of faith,” the report began. “Some still search for a statute of limitation on morality, attempting to forget the longevity of the residue of injustice that at best can leave little room for the healing of the heart.”

More recently, the events of the Tulsa massacre received fresh cultural attention when they were depicted in the 2019 HBO series Watchmen.

At the May 2021 congressional hearing, the three known remaining survivors — Fletcher and her younger brother, Van Ellis, and 106-year-old Lessie Benningfield Randle — pleaded to Congress to see justice in their lifetimes. They spoke about their frustrations that Tulsa and Oklahoma officials use their stories to raise money, but they’ve never received any reparations.

“On this day i’m going to utter the word reparations,” said Sheila Jackson Lee, to cheers, before asking everyone to kneel.

In Tulsa, dozens of events are commemorating the 100th anniversary, from art exhibits and music performances to lunches that honor the survivors, as well as panels on reparations and the inequalities still present today.

The official events have been organized by the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, which raised over $30 million from corporate and government donors to build a museum, Greenwood Rising, which was supposed to open to the public Wednesday but is not yet complete because of building delays.

On Monday afternoon, in a baseball field in Greenwood, singer John Legend had been scheduled to perform, and voting rights advocate Stacey Abrams was set to speak at a televised event called "Remember and Rise." But organizers suddenly canceled that event Thursday evening.

The three survivors, who are suing the city for reparations, had refused to take part in events held by the commission, furious that despite the millions raised, no money would go to the families of survivors or their descendants.

Commission organizers declined to say whether the event was canceled because Legend and Abrams did not want to participate in programming that did not include the survivors. In a statement, Legend said he supported reparations for the survivors and the descendants of victims.

A candlelight vigil is set to be held at 10:30 p.m. Monday, the moment the first shot was fired in Greenwood 100 years earlier.

The trio of survivors were honored Friday as they led the Black Wall Street Memorial March, a small parade that for more than two decades has been held annually down Greenwood Avenue on the weekend of the massacre. Sitting in a carriage festooned with flowers, they passed a small group of Black Tulsans who lay down on the street before them out of respect.

“We are one America,” said Van Ellis, holding one finger up to the sky.

“we are one america” said Uncle Red as he rode past. the collective age of the three people in this carriage is 313 years old! and although there’s a few dozen people around watching, there are not many people out to watch the parade go past.

On Tuesday, President Joe Biden will travel to Tulsa to meet with the survivors and deliver commemorative remarks. In a proclamation Monday, he acknowledged the suffering of survivors and the financial effects not just of the destruction in 1921 but also of the decades of racist policies that followed.

“The Federal Government must reckon with and acknowledge the role that it has played in stripping wealth and opportunity from Black communities,” the president’s proclamation said.

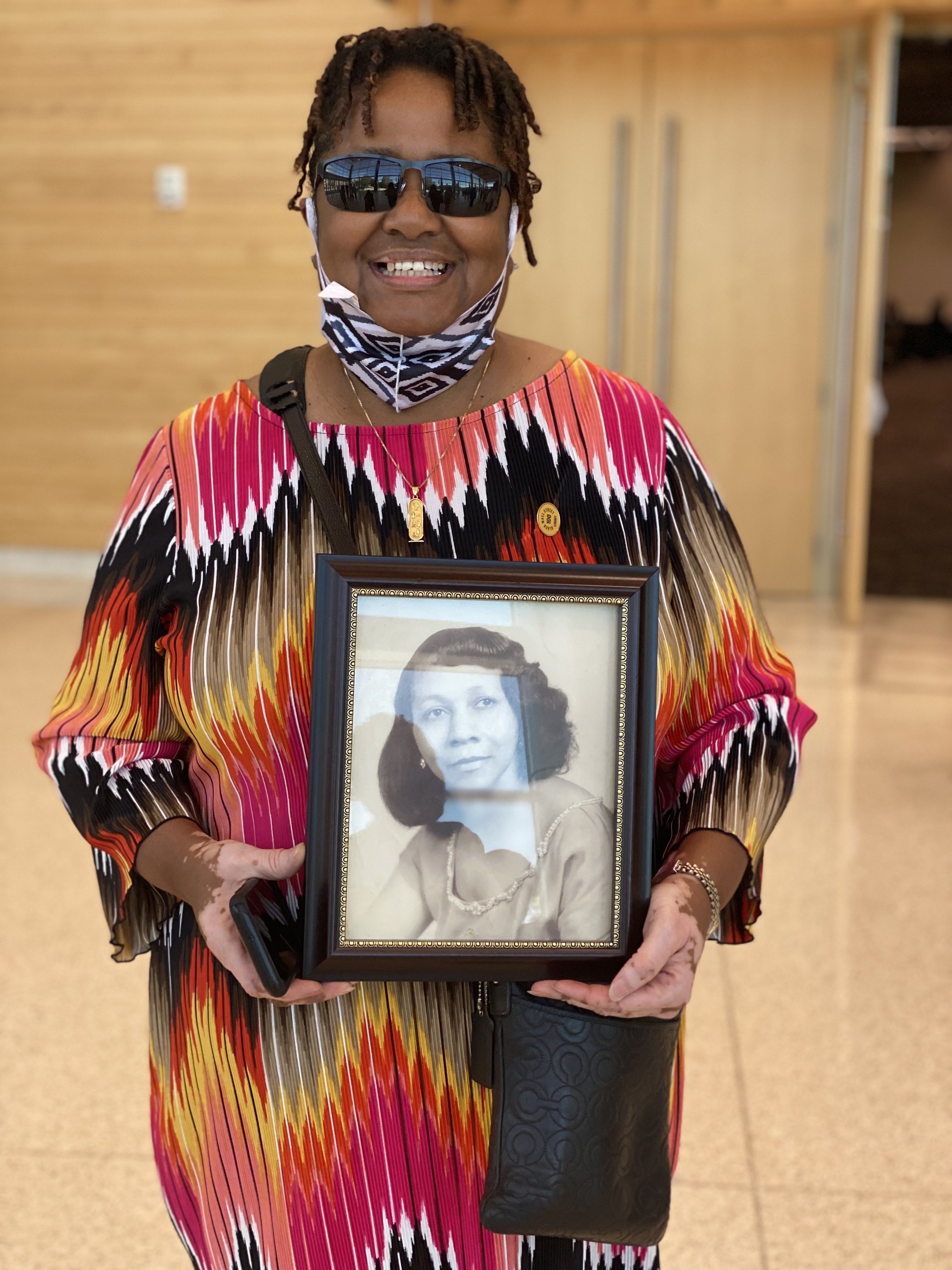

On Saturday, Cherri Lewis, 61, proudly held a photo of her grandmother Eldoris McCondichie at a luncheon hosted by Legacy Festival, a series of events organized by massacre descendants and survivors and not affiliated with the commission.

McCondichie was 9 years old when she survived the massacre that destroyed her community. She died at age 99 in 2010, another of the survivors to live until old age — but not long enough to see justice.

“Hopefully, people will begin to open their eyes and recognize that this is a tragedy that took place in the United States,” Lewis said, echoing the calls of others for reparations. “I think it’s past due.”