When I was 3 and a half, my family – after years of being vaguely itinerant – moved permanently from my native Canada to a small town in France. I guess I’m an immigrant; I just don’t get called that because I am white, Anglo-Saxon, and middle-class, and I came from North America rather than to it.

Instead I get called an expat. Which is a way of saying I’m not visibly un-French, and as such get to bypass a thousand and one obstacles I would have faced if anything other than my passport marked me out as foreign. But even so, I have always felt awkward answering the question I have been asked over and over my whole life: “So do you feel more Canadian or French?” It took me a long time to figure out that the answer is neither. In the end, I am bicultural in some aspects and totally culturally disconnected in others. I also come from the generation that is the first to be internationally pop-culturally connected in a different way: online.

I learned the language quickly, after being dropped into the very French-ly named “Joan of Arc” kindergarten. But French was exclusively the language of school, and friends, and English was the language I spoke at home, and in which I did anything that was for fun. At home we watched English and American shows and movies, for instance. This naturally excluded me from any conversation about pop culture my friends were having, and, equally, they had no point of entry into my world of English-language media. For a while I tried to I make an effort to read popular French comics, but Tintin bored me where Calvin and Hobbes didn’t. When, in 2002, Astérix et Obélix : Mission Cléopâtre came out in cinemas and became an overnight hit, I ended up seeing it just so I wouldn’t be left out while everyone else was quoting it around school.

I am bicultural in some aspects and totally culturally disconnected in others.

On the other side of the cultural divide, I spent my summers at a camp on lake in Ontario. In theory, this should have solved the problem of the linguistic divide, but North America was impossibly ahead of Europe pop-culture-wise. The summer blockbusters everyone there had seen wouldn’t come out until the fall in France, and while Britney Spears made it across the pond to us, NSYNC didn’t. I was left trying to pick up context clues from their conversation so I could pretend I knew who Justin Timberlake was all along. I was as culturally adrift in English as I was in French, it turned out.

And then there were books.

The very first time I used the internet was to buy a book. Specifically it was to buy a volume of the Boxcar Children series on Amazon. I remember that Saturday morning weirdly distinctly, sitting with my dad in his office and spending hours carefully selecting which volume of the many adventures of Henry, Jessie, Violet, and Benny I wanted. This sudden appearance of the internet in my life would turn out to be a game-changer, but it would take me a while to realize the full potential of it beyond just the ability to have books delivered to me.

In keeping with the rest of my pop-culture consumption, I read exclusively in English, so my friends and I had no common reading experience. The Boxcar Children wasn’t out in French and the Fantômette books, which my friends were reading, weren’t translated into English. I shaped habits of keeping books to myself because of this and at some point, I took it one step further than not being able to share interests. Reading became an intensely secret and personal part of my life. I internalised books in a way you only do when you’re first finding things on your own, and you sense that this book was written just for you, and you can’t help but feel that revealing anything about it might potentially be revealing something vulnerable and personal.

I don’t think I was even really conscious of how much I was doing this until some of my books started being passed on to my younger brother. Presumably he was more responsive than I was when my parents asked “what are you reading?” because I remember one night hearing, from the other side of the hallway, the whole plot of a book being laid out for my mother as he was being tucked in. After she was gone, I crept across the hall to his room to ask him very seriously if he would mind not telling my mother about the contents of the books. He didn’t understand what I was talking about, or why something that was in the pages of a book anyone could pick up should be a secret. But at the time this seemed like a huge violation of my privacy, that he was laying bare an integral part of my private internal life to someone else.

There were two books that would change this for me.

The first of them was handed to me by my dad, soliciting a sceptical eyebrow raise from me. I had asked him to order me something specific off Amazon, and this other book he brought home from the post office wasn’t it. He told me he had read an article about this series in the paper and he thought I might enjoy reading it. I said I supposed I could give it a shot, but could he be sure to order me that other book which I had asked for. The book he’d handed me was called Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. You may have heard of it.

Everyone of my generation has a Harry Potter story of some kind. I was 11 when I got my hands on the first three volumes, and I was finishing my first year of university when the last one came out. It quite literally bookended my whole young adulthood. Unlike every other book I had read up to that point, it also existed in French. And because it was a massive phenomenon that crossed borders, the rest of my school read it too. And we talked about it.

Sure, there were some small barriers to sharing our thoughts about the boy who lived, having read the books in different languages. We pronounced Hermione in different (equally wrong) ways, and Hogwarts in French is called Poudlard (which literally translates as “Lice of Lard”), so my attempts to say “Hogwarts” with a rolled French “r” were met with confusion.

But, still, it was a universal phenomenon, a cultural touchstone I shared with friends and classmates. I learned the expression “Nuit Blanche” from a classmate when we were talking about reading Harry Potter, a French idiom for “pulling an all-nighter”, in this case to finish Prisoner of Azkaban. I also learned from him that he was also a huge Indiana Jones fan, which I never knew due to my aversion to sharing things I liked with anyone.

In distinct contrast to my chastising my brother for revealing intimate plot details, I remember walking into his room just as my mother had finished reading "The Boy Who Lived" to him, in order to ask him how much he hated the Dursleys. He looked at me blankly because all he knew of them at that point was that they lived at number four Privet Drive and were proud to say they were perfectly normal thank you very much. “You will hate them,” I promised him smugly, turning to swan back across the hallway to my own room and wait for him to read chapter two so he could join me in my feelings of righteous indignation of the treatment of young Harry.

When Goblet of Fire came out, our local bookshop hosted a fan event. I went along to it, dragged by a friend whose mother ran the bookshop. I was still not entirely sold on flaunting my likes so publicly. I’ve always cared far more than is healthy what people think of me, and I was still not sure about opening myself up to potential scorn by revealing something I loved. At the event I ran into another girl I knew, someone I had always counted as one of the cool girls who had grown up just a bit faster than the rest of us and who I’d never have guessed was a HP fan. A local journalist interrupted our conversation to get a quote about why we had come that afternoon. And if she wasn’t afraid to admit her love of the Wizarding World, I supposed I could put myself out there too and own it. Years later, she and I would end up in multiple school theatre productions together, if you want to talk about really putting yourself out there to be judged by others.

The second book was the one that engaged me online instead of with my peers.

Games of Thrones came to me just I was running out of YA fantasy and had started to move semi-reluctantly into the realm of adult fantasy, where I was struggling to find the same interesting and badass women I had learned to love in teen books. I have the Amazon “if you liked X you might enjoy Y” recommendations to thank for bringing the epic saga into my life at an inappropriately young age. Game of Thrones might have looked like any other fantasy, with a cover displaying a dark-haired hero astride a horse in the snow, but as anyone who has seen the TV show will know, Game of Thrones ain’t just your average fantasy series. It’s huge and sprawling and desperately clever and incites the sort of ardour that justifies the etymological meaning of “fan”. And it completely hooked me. I came for Arya Stark, who reminded me of the gumption-filled, gender-role-defying, cross-dressing heroines I had loved in YA, and I stayed for, as it turned out, for the online theories.

Much as with Harry Potter, the first three books of the saga were out by the time I came to the series, and I tore through them. And I didn’t flip ahead. Which is a rarity for me. I am not a patient reader. And suddenly I was done and I had an obsession and a multiple-year wait until A Feast for Crows was released. And for the first time I wandered on to the internet looking for somewhere to put that obsession.

I found a Game of Thrones fan forum, and immediately started catching up on all the theories developed by people who had already been reading for five years and who had been waiting for A Feast for Crows since before I arrived. I got caught up on the (as we now know) ironclad R+L=J theory, the speculation that Tyrion is a secret Targaryen. I read and reread the "Three Eyed Crow" and "House of the Undying Prophecy" chapters to interpret and analyse them. I joined in on conversation about character motivations – Littlefinger’s endgame obsessed me. I engaged in silly conversations with people I had never met about which high school clichés the characters would fulfil if they were cast in a John Hughes-style 1980s scenario. And when that ran out, I hunted down fanfiction, because dammit all I have ever wanted in life is for Arya and Gendry to come out of these books alive and together. Though I’d never heard the term at the time, I shipped it. I allowed other people’s obsessions to feed mine.

Nowadays, seeking out online communities seems natural to everyone. And I’m sure that if I were 16 in 2017 instead of 2004, it would have been a connection that was made much more painlessly and with less subterfuge than it was. But it did what it needed to, even in the days of dial-up. It was a place that connected me when I was disconnected, linguistically, geographically, and, most of all, culturally.

I don’t feel any less attached to books now than I did when I was a teenager. Telling you about a book or movie I love still feels like baring a piece of my soul. The difference is, I’m now good at baring that part of myself. I will talk endlessly about a book or movie if I’m allowed to. And my book-pusher instincts have grown strong with the Force. I have been known to march people into bookstores to make them buy a book so I have someone to talk about it with.

And beyond that I write my own books. And there’s nothing quite as revelatory of a piece of yourself as sharing not just a book that you love, but a book that you created.

I allowed other people’s obsessions to feed mine.

The thing is, even all these years later, I probably still do care far too much what people think of me, because I don’t think any of us ever totally shed our 16-year-old selves. If I had, I probably wouldn’t write books about teenagers. But there is a big difference a dozen years makes: I realised that being passionate about things, and sharing that, is a huge part of what makes me interested in people, and people interested in me. No one should be a blank slate. I display my fangirlness easily and proudly where I once played my cards close to the chest. I don’t worry anymore about if anyone is silently scorning me because I have theories about Rey’s parentage. And I don’t care if you think I made a poor life choice staying up until 4am to finish a book the night before an important meeting in the office. It’s half the reason I wanted to write for teenagers, because no one is as unabashedly and honestly passionate about things as a teen reader.

And if 16-year-old me had never figured out that it wasn’t enough to keep her interests secret, keep them safe (10 points to Hufflepuff if you get that reference), then I don’t imagine how I would have ever gotten to the point where I could share my own writing, and engage about my own books online on a daily basis. No man is an island, and no fan should be either.

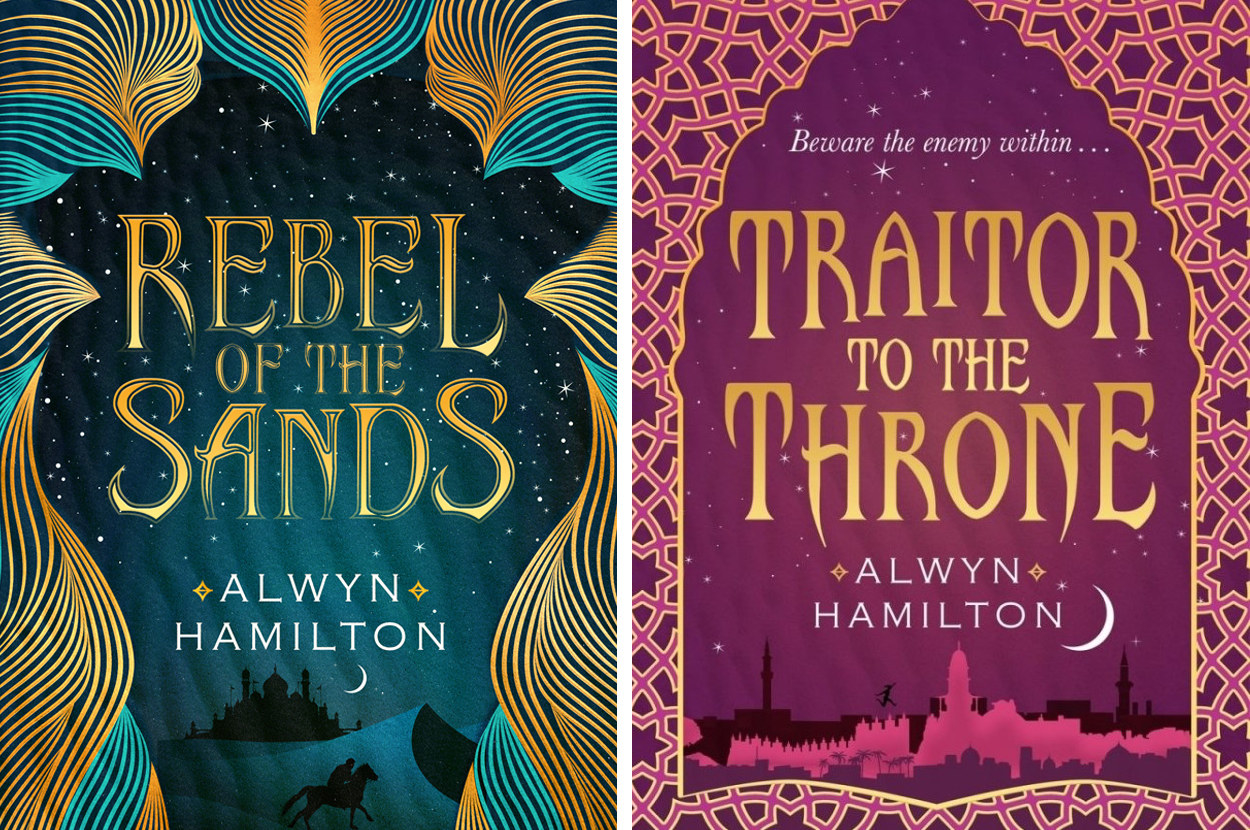

Alwyn Hamilton is the author of Rebel of the Sands and Traitor to the Throne, both out now.