The three friends agreed to meet on Monday mornings, before 9am, at the Georgian townhouse in Mayfair where one of them worked for a right-wing think tank.

Steve Baker, one of the Conservatives’ most committed Eurosceptics, had just been appointed to a ministerial position in the Department for Exiting the European Union. Crawford Falconer, a former New Zealand trade official, was the new chief trade negotiator at the Department for International Trade. Both were now deeply embedded in the UK’s preparations for leaving the European Union.

The third man, their host, didn’t work for the government, but in a different way he was also heavily involved in the political maneuvering around Brexit.

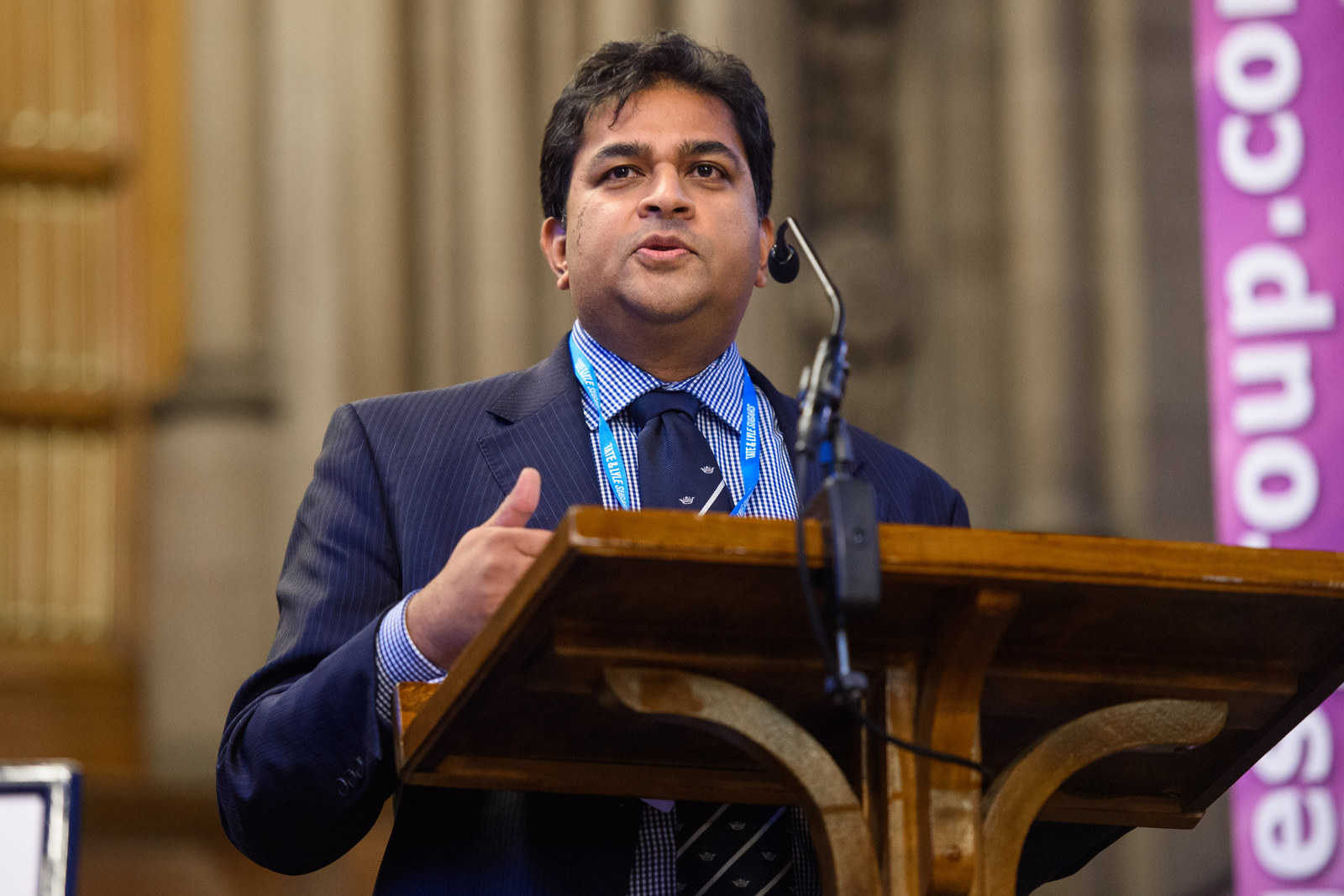

Shanker Singham, a 48-year-old lawyer and free trade campaigner, had become one of the country’s most influential policy specialists in the two years since the EU referendum. As the director of economic policy at the Legatum Institute, he’d built such close links to the Eurosceptic Tories who made the political weather in Westminster that journalists referred to him as “the Brexiteers’ brain”. Environment secretary Michael Gove, one of the architects of the Leave victory, described him as probably the UK’s “leading expert on trade deals”.

Singham had been friends with Baker since the 2016 referendum; they met often to talk about trade and economics while Baker ran the European Research Group, an alliance of more than 70 die-hard Eurosceptic Tory backbenchers. And Singham had known Falconer for 18 years, dating back to Singham’s time as a lawyer and lobbyist in the US. Falconer had been on a panel of trade experts Singham set up at Legatum before he joined DIT. All three shared a fervent belief in free markets and a vision of Britain becoming the new guiding star for global trade outside the EU’s single market and customs union.

In the second half of last year, after Baker and Falconer joined the government, Singham continued to meet both men, BuzzFeed News has established. According to a source who is familiar with the arrangements, Singham saw Baker and Falconer numerous times over several months, outside of work hours, at the Legatum building in Mayfair. This was not disputed by any of the three men or Legatum when it was put to them by BuzzFeed News.

None of these meetings has been disclosed publicly until now.

The government’s ministerial code requires that meetings between ministers and external organisations at which government-related matters are discussed are organised through their departments, with officials present, and disclosed to the public every quarter. The top-ranking civil servants in each department also publish details of their official meetings with outsiders every three months. However, DExEU and DIT’s transparency records for July to December show no meetings between Singham and Baker or Falconer.

Representatives for Baker and Falconer didn’t deny they had seen Singham during that period, but insisted that there were no contacts with him at which governmental matters were discussed. Any meetings were purely social.

“Steve and Shanker have been friends for years,” said a spokesperson for DExEU. “All meetings on official business are declared in the usual way.” A spokesperson for DIT said: “Mr Falconer has known Mr Singham for nearly 20 years and they have not met in an official capacity.”

Neither department answered specific questions about the meetings:

What did they talk about if not Brexit and trade policy?

How many times did they meet?

Was anyone else in the department aware that they were happening?

The DIT spokesperson said that because Falconer said they didn’t talk about official business, there was no requirement for records to be kept or for the meetings to be disclosed to the public. He said it wasn’t the department’s business to press Falconer for more details. It would be inappropriate to intrude on a colleague’s private life. BuzzFeed News had already “established the facts pretty clearly”, the press officer said.

But the revelation that two senior government figures had multiple, undisclosed, unminuted, out-of-hours meetings with a prominent campaigner whose work cuts across their areas of official responsibility – and who has been close to a partisan political group, the ERG, that has actively sought to influence government policy – raises serious questions. It will add to concerns in some quarters about the extensive access Singham has enjoyed to people at the highest levels of the Brexit process.

Singham was already under scrutiny because of his connections to the leading Brexiteers. In November, the Mail on Sunday accused him of being the “third man” in an alleged plot by Gove and Boris Johnson to steer 10 Downing Street into a hard Brexit. Newspapers began digging into Legatum and accused its founder, a New Zealand-born businessman named Christopher Chandler, of having connections to the Russian state. The allegations reemerged this month when they were raised by MPs in the House of Commons. Legatum has vigorously denied that Chandler has had any association to the Russian state. It maintained that he plays no part in the running of Legatum and has no influence over its work. Legatum also denies taking a stance on Brexit.

Despite being a figure of intrigue in the media, relatively little is known about how Singham sprang seemingly from nowhere to play an outsize role in the most important policy debate in British politics in decades.

Interviews by BuzzFeed News with dozens of people over several weeks – and a review of numerous articles, speeches, academic papers, emails and other communications, archived CVs, public records, and other sources – has provided the most detailed account yet of what drives Singham, how he got here, the depth of his political connections, and the resentment he’s provoked among rival trade specialists and Whitehall officials – some of whom “think he’s a total clown”, in the words of a Conservative adviser.

In March, Legatum abruptly announced that Singham was leaving. After two years at the institute, he was taking a team of three analysts to set up a new trade and competition unit at the Institute of Economic Affairs, a free market think tank in Westminster.

“It’s very amicable,” Singham said of his departure, speaking to BuzzFeed News at the IEA’s office a few blocks from parliament. He had only positive things to say about Legatum and insisted the press had it wrong about Chandler, though he was happy to have moved. “I think this is a better place for the work that I want to do,” he said.

It was a Wednesday morning in April, and Singham had been at his new professional home for about a month. He wore a dark suit, a patterned red tie, and braces. In his writing, Singham can be grandiose at times, but in person he came across as agreeable, courteous, and calmly persuasive. In a 90-minute interview and multiple follow-up emails, he seemed keen to play down the fuss about his work, to present himself as an ordinary policy wonk.

But Singham isn’t an ordinary policy wonk. Since the referendum, dozens of think tanks, academic institutions, and consultancies have competed to fill the gulf in expertise in Whitehall, advancing various solutions for the government’s huge policy challenges – but none have been as successful at steering the political conversation, or got as close to the politicians driving the debate, as Singham has.

Official meeting records, emails, and interviews show that Singham has had regular access to ministers and officials who are closely involved in Brexit. Less visible, but perhaps more important, is his relationship to the ERG, which is now chaired by Jacob Rees-Mogg.

The most powerful faction in the Conservative party, the ERG has put enormous pressure on Theresa May to make a clean withdrawal from the EU. In recent weeks, as a dispute over the customs union became the fiercest battlefield in British politics, the group has repeatedly intervened to squeeze 10 Downing Street. Some of its members have threatened they will challenge May’s leadership if she doesn’t comply with their demands.

In the last two years, MPs in the ERG have drawn heavily on Singham’s ideas and research to bolster their arguments. He admits attending their meetings. And, according to communications seen by BuzzFeed News, reported here for the first time, he was included in private discussions between the tight-knit group of MPs and peers who run the ERG. There are no rules against MPs including external advisers in their communications, but it does indicate how much trust the ERG’s inner circle placed in Singham.

With the fighting between the Tory factions intensifying recently, Whitehall insiders say they’ve detected Singham’s fingerprints on several occasions. Some officials believe that a letter sent by Boris Johnson to 10 Downing Street in February, setting out the foreign secretary’s views on the Northern Irish border, drew on Singham’s ideas.

And then there was the 30-page memo the ERG sent Downing Street at the start of this month attacking May’s preferred option for a new customs system. Among the ERG’s boldest attempts yet to sway the prime minister, the memo was leaked to the press the night before an important meeting of May’s Brexit “war cabinet”. Some of the arguments about trade policy came from Singham, such as a claim that a new alliance of like-minded free-trading countries led by the UK would boost the world economy by $2 trillion over 15 years if they removed just a fifth of the anticompetitive regulations across their markets.

Singham became the Brexiteers’ guru on trade because he advocates a vision that fits with their grand ambitions for a thriving, self-confident “Global Britain” that will once again command respect internationally. Most mainstream experts are gloomy about the UK’s prospects after Brexit. They think it’s foolish to pull away from its biggest market; that no new alignment of Britain’s trading arrangements can come close to making up for what it will lose by leaving. Singham says the opposite. Britain will flourish on its own. Leaving the EU’s orbit, pursuing new trading alliances with the US and the Commonwealth, joining the Trans-Pacific Partnership and NAFTA, adopting a lighter, more business-friendly approach to regulation: These will not just transform the UK economy, he argues, but rejuvenate the entire global trading system.

Singham sees Brexit as being about more than reclaiming the UK’s sovereignty – as part of a bigger, existential fight for the future of the world economy. Humanity is at a pivotal juncture, Singham believes, facing a stark moral choice between fundamentally different visions of how to govern an economy. Right now, the populists are in the ascendancy. People across the West have lost faith in the power of capitalism to improve their lives. But the UK has a chance to turn it around. It can be a torchbearer for economic liberty. Brexit can be the start of a new era of prosperity – if our political leaders have the courage to do it the right way.

It's a “unique moment to deliver the staggering wealth creation possible for mankind”, Singham wrote in one paper.

“We are embarking on a process with the rest of the world which could improve the lives of billions of people,” he wrote in another. “They are counting on us and we must not fail them.”

Singham’s supporters say he’s exactly the sort of person Britain needs at this moment. A world-class economist and trade expert. A brilliant thinker. Visionary. Principled. His CV includes several glowing testimonials from political figures he’s met over the arc of his career:

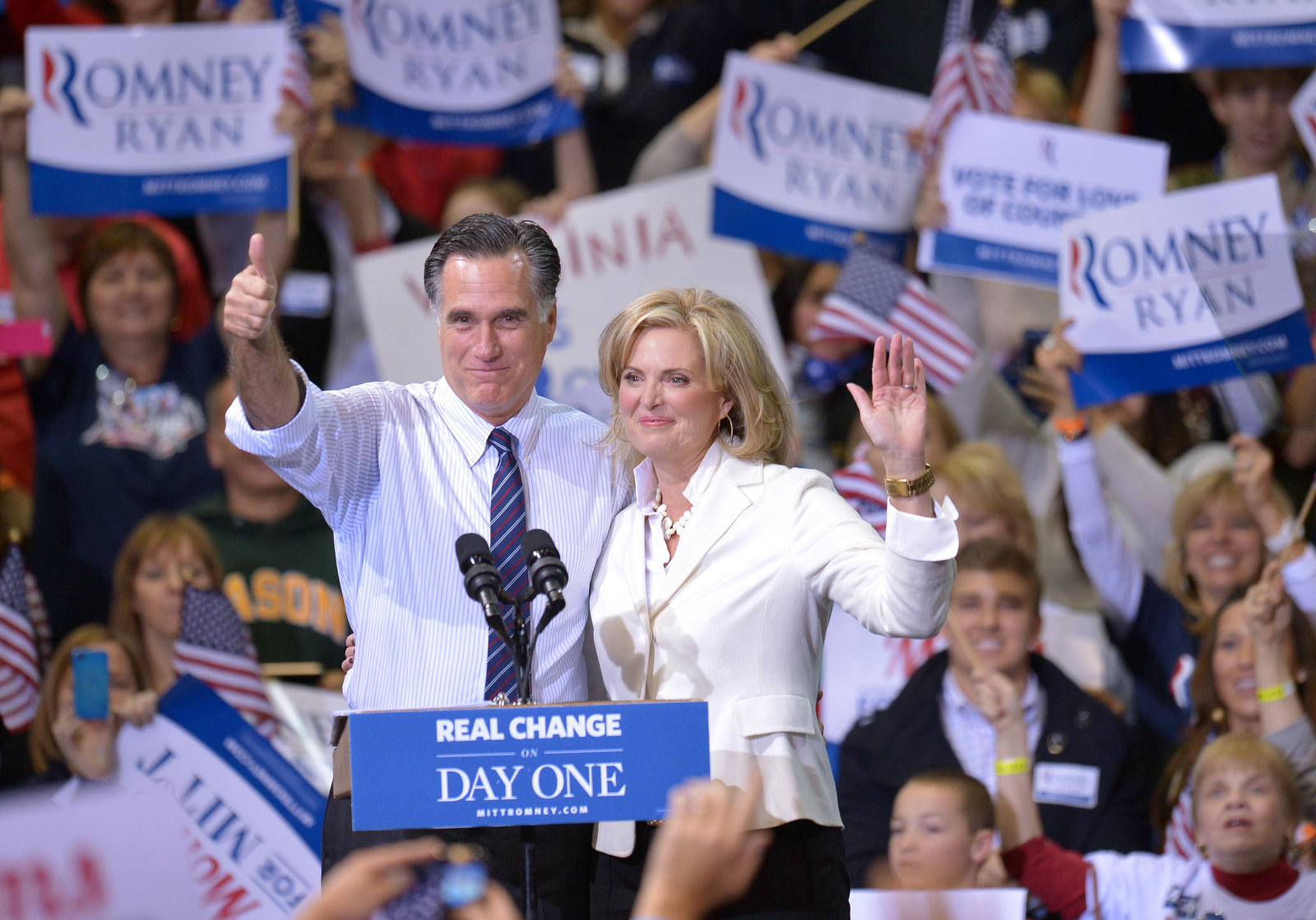

“I believe Shanker is the most brilliant conservative economist of our generation,” said Kerry Healey, a former lieutenant governor of Massachusetts (who met Singham through Mitt Romney’s presidential campaign in 2012).

“In my opinion, Shanker is one of the world’s greatest economic thinkers,” said Admiral John Poindexter, a national security adviser to Ronald Reagan in the 1980s (whose wife, Linda, was Singham’s spiritual adviser when he converted to Roman Catholicism in Washington, DC, in 2014).

This infuriates Singham’s detractors.

BuzzFeed News spoke to multiple economists, policy wonks, Conservative advisers, politicians, and journalists who said they’re baffled that he’s become so prominent in the Brexit debate. They say his standing in the trade world has been overblown. They don’t dispute that he knows the subject, but most hadn’t heard of him before he emerged at Legatum. They find it exasperating that he’s been portrayed in the UK as a vastly experienced trade negotiator, as if he were one of the decision-makers in the room when the world’s biggest trade agreements were hammered out. He wasn’t that close to the action, they say.

“He was basically a lobbyist,” said a trade specialist who has known Singham since the 1990s.

They think he got lucky. Right place, right time. He got access to politicians because he told them what they wanted to hear. His plans for Britain’s future trade policy, they say, are fanciful. He overstates the benefits of new free trade deals, glosses over the costs and complexities of pulling away from the EU. And the calculations he’s used to justify his claim that Britain's would be better off leaving its biggest market, they believe, are flawed.

“He’s saying things that people like Liam Fox wish were true,” said Peter Holmes, an academic at the UK Trade Policy Observatory at Sussex University.

It's not uncommon for Singham’s critics to reach for fictional comparisons when trying to describe him. Walter Mitty. Gatsby. Chauncey Gardiner, the character played by Peter Sellers in the film Being There: a simple gardener who rises to prominence in Washington after his banal remarks are mistaken by the political elites for profound wisdom.

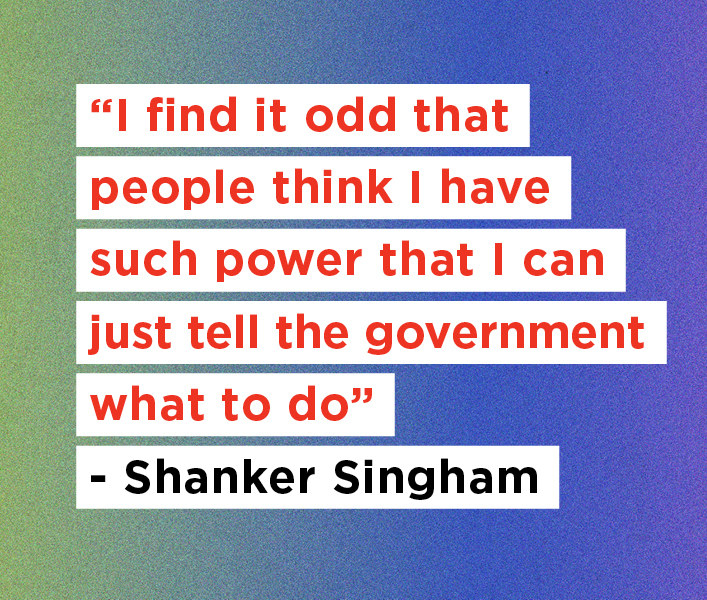

When BuzzFeed News repeated this to Singham, he said: “Either I’m a deluded Walter Mitty fantasist or I’m meaningfully influencing the government’s thinking at the very highest levels. Pick one.”

Others who know Singham advanced a simpler view. They said he’s merely a lobbyist using a tried-and-tested Washington playbook to swing a policy argument in his favour. They don’t agree with his analysis or his prescriptions, but they admire how successfully he’s managed to put himself at the centre of the conversation.

“The UK has never seen DC-style political entrepreneurship of this kind,” said Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, director of the European Centre for International Political Economy, a Brussels think tank. “Many academics are riled by his success and take it rather personally. But in the end he accomplished something astonishing.”

Singham didn’t give much thought to leaving the EU before June 2016. But when the vote happened, he felt a sense of destiny. His whole career had prepared him for this moment.

Singham was born in London in 1968, the second of two children. His parents migrated to the UK from Sri Lanka in the 1960s; his mother was a microbiologist and his father an accountant. Singham went to St Paul’s, where he overlapped with George Osborne, and then studied chemistry at Balliol College, Oxford. He represented the university at the 400 metres and wrote novels in his spare time, though he has never had one published. After briefly considering becoming a criminal barrister, Singham joined a City law firm in 1992.

It was in America that Singham’s driving ambition was formed. In 1995, aged 27, he moved to Miami to work for a law firm named Steel Hector & Davis. At first, the British public school boy was out of place in the hard-driving, eat-what-you-kill American legal culture, where lawyers didn’t just stay in the background giving advice but acted as lobbyists and political fixers. But colleagues recall that he was smart, hard-working, and hungry, and he rose quickly.

“Clients liked him,” said Joseph Klock, the managing partner at Steel Hector at the time. “People liked him. The folks at his church liked him.”

Singham spent a decade in Miami, then eight years in Washington, DC. His work focused on helping big companies get around trade barriers in overseas markets. Public records from the time show that he lobbied Congress and government departments on behalf of Cuban billionaires who were trying to recover a painting that had been confiscated by Fidel Castro, a Russian businessman with mining interests in Mongolia, and a powerful trade body for the US cotton industry. He represented a group of technology companies on a committee of major exporters that advised the US government on US trade policy, which required him to have a security clearance.

“Shanker was a well-respected lawyer who not only knew trade law but was also very much into developing policy in the trade space,” said Francisco Sánchez, a former colleague of Singham’s at Steel Hector who was Barack Obama’s undersecretary of commerce for international trade from 2010 to 2013.

Singham’s critics in London don’t dispute that he was a reputable trade lawyer during his time in Washington, but they’re not convinced that anything in his experience marks him out as especially well-qualified to help the UK navigate Brexit. Several said they’d never heard of Singham before he joined Legatum. Some did come across him in Washington, but said he didn’t strike them as one of the people in the field that you had to know to get things done.

David Henig, a former UK trade official who visited Washington regularly during the negotiations on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), the proposed trade deal between the US and EU, said: “I was heavily involved in TTIP for three and a half years, and I didn’t come across him once during that period. As that was the big show in town, you would’ve thought I would come across him.”

During his years in Washington, Singham became active in politics. In 2008 and 2012, he was one of several trade specialists who sat on a volunteer advisory panel to Mitt Romney’s presidential campaigns. On several occasions, including on his current CV at the IEA, Singham has described his role in Romney’s campaign as that of a “senior” adviser. In an interview, he told BuzzFeed News he met Romney several times and contributed one of his key trade policies: a free trade prosperity zone, similar to the concept he’s now advocating that the UK adopt after Brexit.

BuzzFeed News contacted several former Romney staffers to get more information about Singham’s role in the campaigns, but some of them cast doubt on just how “senior” and closely involved he was.

Romney’s 2008 policy director, who was responsible for policy advisory groups, told BuzzFeed News she didn’t remember him. The 2012 policy director said Singham was one of several outside specialists who helped shape Romney’s trade policy that year, and had been “a genuinely helpful part of the team”. Kevin Madden, one of Romney’s senior staff on both campaigns, said: “I have no recollection of the name. … In my capacity I only really dealt with the candidate himself and true senior staff. … Campaigns always have a universe of volunteer policy advisers who are used for input and feedback … but you really aren’t a senior adviser unless you were paid, day to day staff, and were in regular meetings with the candidate himself.”

Singham also claims to have been a “senior trade and economics adviser” to Marco Rubio when he ran for the Republican nomination in 2016. BuzzFeed News attempted to verify this and was told by a former Rubio aide: “Neither the communications team nor our campaign manager have ever heard of him. Our policy adviser isn’t sure if/what role he had, but said that he definitely never would have talked to Marco. … We had a very large ‘trade policy working group’ that he may have been a member of.”

Singham insisted he made an important contribution to the Romney and Rubio campaigns and did talk to both candidates. “Campaigns tap up the best trade minds they can find to sit in small working groups on policy matters. I served on those for all three [Romney and Rubio] campaigns. These committees met regularly and I was engaged with them all in putting trade policy proposals on the table for the candidates.”

It was a damp tropical evening in March 2013 when Singham took the stage at the Ocean Reef Club, an exclusive resort in Key Largo, Florida. He was there to give a talk about “the moral case for free markets”.

Nearly two decades after moving to the US, Singham was growing restless. The global trading system was in crisis. Over his career, he’d come to believe strongly that open competition between private enterprises, unhindered by government interference, was the only way to grow economies and lift people out of poverty. In parallel to his legal practice, he regularly gave speeches and wrote articles arguing the case for free trade and open competition. As he got older, he became more evangelical about it. The role of government, Singham wrote in one paper in 2012, should be limited to protecting its citizens’ physical safety, private property, and economic liberty; everything else should be left to the invisible hand of the market.

By the time of the 2012 presidential election, Singham was gravely concerned about the direction the US was heading. After Romney lost to Barack Obama, he considered running for office himself, as governor of Maryland. Singham embarked on a speaking tour to make the case for free enterprise, one small venue at a time. He gave a talk to a libertarian campaign group at a community hall, and to a group of parents at his son’s Roman Catholic school in the Maryland suburbs. Now, he was addressing an audience of wealthy conservatives on a Monday evening in the Florida Keys.

Trillions of dollars were being wiped out every year because governments meddled in markets, Singham told them, and in future it would be worse. Chinese-style state capitalism and the backlash against free trade in the West would plunge millions into poverty and despair, unless people like them did something about it.

“History will judge whether we answered the call or whether we were found wanting in the balance,” Singham said.

On a Thursday morning in September 2016, a few months after Britain voted to leave the EU, Steve Baker rose to his feet in parliament and urged the new trade secretary Liam Fox to take Singham’s advice.

“A team of skilled, experienced, first-class international trade negotiators has been assembled at the Legatum Institute’s special trade commission,” Baker told the Commons. “Will my right honourable friend consult the commission and listen to its proposals for a much larger prosperity zone than the European Union?”

Singham was watching in the public gallery above. He had moved back to the UK and joined Legatum at the start of 2016. Singham hadn’t campaigned for Brexit; nor had he seen it coming. “I just assumed, like everyone else, that they’d vote to remain and that would be the end of it,” he told BuzzFeed News. But when the result happened, he saw an opportunity and moved quickly.

Raised the @LegatumInst Special Trade Commission at the first Trade questions - vital we draw on expert experience https://t.co/uuvuFs3fzY

Weeks after the referendum, he formed a “special trade commission”, pulling in several of his contacts from his time in Washington – former officials from countries such as Australia, New Zealand, and Canada who had the sort of high-level experience that the UK would now desperately need. Crawford Falconer was one of them. It was a brilliant piece of marketing, which instantly elevated Legatum’s credibility in the field.

Singham churned out policy papers. He gave evidence to parliamentary committees. Journalists began calling to seek his views. Soon, it seemed there couldn’t be a public discussion of Britain’s trade relationships without Singham involved. At the same time, he was tirelessly cultivating contacts in government. And doors were opening. Government records show that Singham had numerous meetings with cabinet ministers and top-ranking officials. When the Brexit department held a summit of business leaders at Chevening, the foreign secretary’s traditional country home, last summer, Singham was the only think tank expert who attended. In the space of a few months at the end of last year, he met Greg Hands, the trade minister, no fewer than six times.

“I hope we can meet frequently and monthly is a good objective,” Hands wrote to Singham in October, according to emails obtained by the campaigning website Open Democracy.

Liam Fox appointed Singham to a five-member “committee of experts” set up to advise DIT on trade and investment. And when Fox’s department appointed a chief negotiator to help broker the new agreements Britain would need after Brexit, it was at Legatum, on Singham’'s special trade commission, that they found their new recruit: Falconer.

Gove and Johnson, the two most influential Leavers in cabinet, also relied on Singham’s counsel, according to several Conservative sources. “He has a lot of influence,” said one person who is close to Johnson. “He’s been a massive driving force in the intellectual and political argument.”

Singham also had a close relationship with the Leavers on the Tory back benches, in the ERG.

He became friends with Baker, meeting regularly to talk about “trade, free markets, competition and other issues”. Baker embraced Singham’s vision of a new UK-led free trade prosperity zone. Baker tweeted praise for Singham’s “definitive contribution” to Brexit policy and his “authority based on experience”. During a meeting with Baker in his parliamentary office in early 2017, Baker gave BuzzFeed News a copy of a policy blueprint written by Singham, Trade Tools for the 21st Century.

.@ShankerASingham is making the definitive contribution, demonstrating expertise available to UK via @LegatumInst Special Trade Commission https://t.co/5nkMXhzGHz

After Baker became a minister last summer, Singham continued to have a close relationship with the ERG. Its MPs circulated Singham’s policy papers in the WhatsApp group chat they used to coordinate their parliamentary campaigning, according to messages leaked to BuzzFeed News. And Singham was looped into communications between the senior leaders.

“There are members of the ERG that I certainly know well,” Singham told BuzzFeed News, when asked about his relationship with the group. He confirmed that he had spoken at their meetings, but said he had no official role with the ERG and that was only one of several political groups that he’s dealt with. “I make myself available to anyone. If a group of MPs said, ‘We want you to come in and talk to us and be a resource for us on Brexit and trade issues,’ then I think it’s my responsibility to do that.”

Asked about his meetings with Baker after Baker joined DExEU, Singham said: “I meet with a lot of people and he was one of the people that I would meet with.” A spokesperson for Legatum confirmed that Singham had met Baker after Baker became a minister, although Legatum would not comment on the timing or location or Falconer’s involvement.

Baker’s spokesperson confirmed they’re friends but said he didn’t meet Singham during the period to discuss official business, and would not comment further.

On Falconer, Singham said in an email: “Crawford Falconer and I have known each other since 2000, and are also friends, and regularly meet to discuss international trade issues generally.”

A press officer for DIT confirmed that Falconer had continued to see Singham after he joined the government, but said they were merely social engagements out of work hours, where government policy wasn’t discussed, and therefore didn’t have to be disclosed.

The press officer said that BuzzFeed News’ account of the meetings had been put to Falconer and he didn’t dispute the details, except to say that they met in the coffee shop in the basement of the Legatum building, rather than Legatum’s office. The press officer said he didn’t know how many times they met, over what time period, and what they talked about. And he refused to push Falconer for more details. “He met him for coffee, as friends; they’ve not had an official meeting,” the press officer said. “No government information was shared. And what two individuals do, in their own time, is their business.”

On his meetings with politicians, Singham said there’s nothing unusual about a think tank taking an active role in policy formation. And he insisted there’s nothing exclusive about his work – he’s happy to work with anyone regardless of their party, ideology, or whether they voted Leave or Remain, if they want his advice.

“If Jeremy Corbyn said to me, ‘I want to meet with you every day to talk about Brexit,’ I would meet with him every day to talk about Brexit,” Singham said. “I would meet with whoever wants to meet me.”

He knows there are sceptics. It doesn’t seem to get to him.

In February, Singham took part in a head-to-head debate with the Financial Times commentator Martin Wolf at King’s College London. It was a characteristic Singham performance. In front of an audience of nonbelievers, he made the optimistic case for Brexit sound so reasonable that one of the organisers, a critic of Singham’s, said later: “If you didn’t know anything about the subject you’d think Shanker Singham had won.”

When the debate was finished, an academic named Michael Gasiorek came up to speak to Singham.

Gasiorek, a senior economics lecturer at the University of Sussex, had been examining Singham’s claims about the potential economic benefits of removing market distortions – the model that produced the $2 trillion claim in the ERG’s memo to Downing Street – and was unimpressed. Speaking to BuzzFeed News, Gasiorek said there was so little information in Singham’s published papers about how he arrived at his conclusions that it had been difficult to replicate. Gasiorek didn't think the methodology was correct or that the evidence was strong enough to justify Singham’s conclusions. It wasn't academically credible, Gasiorek concluded – and he was willing to say that on the record.

But when Gasiorek approached Singham after the debate, Singham appeared unruffled. “He’s very suave and glib,” Gasiorek said.

Gasiorek isn’t the only person who has a problem with Singham’s work. BuzzFeed News spoke to several economists and trade specialists who said they don't regard his assertions about Britain’s prospects after Brexit as realistic. Singham is smart and knowledgeable about international trade law, one said, but he underplays the complexities and costs of leaving the EU and presents as plausible scenarios that most experts believe are incredibly unlikely.

In Whitehall, some of the civil servants working on Brexit share these doubts and are concerned that politicians have listened to him too much, several people said. “They think he’s a total clown”, said a Conservative adviser. “Like any of these Brexiteers, he comes up with these ideas that aren’t workable. He’s a good blue-sky thinker, but on the practicalities and details he gets blown apart.”

.@ShankerASingham provides advice on trade to anybody who asks. Government, Parliament and the Civil Service seek his advice because he knows what he’s talking about. It really is that simple.

Singham stands by his work. He said he’s secured a $1.1 million grant for a three-year research project on anticompetitive distortions in international trade from the Templeton Foundation, which funds research on science, free markets, and religion. The foundation undertook an “extensive, peer-reviewed analysis” before awarding the grant, Singham said.

“The views that attack my expertise are amply rebutted by those who believe me to be one of the world’s leading experts in this area,” Singham said.

He seemed slightly baffled by the griping. As he sees it, he’s just one of many policy specialists putting forward a point of view on Brexit. He’s not stopping anybody else from doing the same. If decision-makers in government find his solutions useful, they’ll listen; and if they don’t, they won’t. “I am not the decider here,” Singham said. “I am not the only person making this call. I find it odd that people think I have such power that I can just tell the government what to do.”

Singham’s determination to see Brexit done his way is unwavering, said a former colleague. “He’s a true believer in all of this stuff. And he thinks that all he’s doing is really just trying to explain the obvious to people who just don’t quite get it. He comes from the standpoint that it really needn’t be this complicated. You can do this if you want to do this.”