In Kiribati culture, songs have a special power. A song can make you fall in love or make your enemy drop dead in the street.

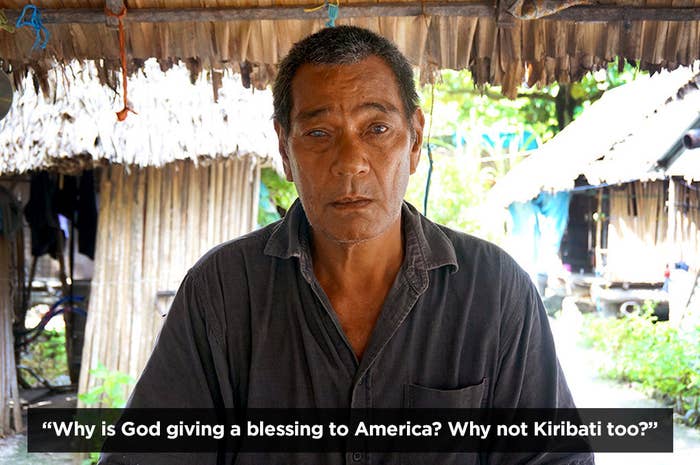

“In our culture, if we create songs, the words and rhythm of the song are a kind of black magic,” explains village leader Timeon Tion through a translator. We are sitting in his buia, a traditional raised hut in the North Tarawa village of Buariki.

“For example, if I compose a song for you to love me, straight after the public hear the song you will come and kneel down and ask to marry me. That’s the belief. And if I come and compose a song to kill you, within three days you will be buried, according to the rhythm and the words.”

Now Timeon is hoping for a song to save his drowning island.

“These big countries keep building their factories and coal mines, and in low-lying countries the water level is going to climb up to here, then up to here,” he says, bringing his hand first to his chest, then to his chin.

Then he raises his hand just above his head.

“When the water is here, that is the end of us.”

He doesn’t dwell on it, or pause for effect. It’s just a fact.

“So in the future we will lay down and sing God Bless America, so America will come and help us.”

Kiribati is a low-lying island nation in the Pacific Ocean in desperate need of help.

Made up of 32 coral atolls and one raised phosphate island scattered like jewels across the Equator, it's feeling the effects of global warming right now. Most of the land is only two metres above sea level, and people's lives are being impacted by wildly fluctuating weather patterns, vicious storms and a steadily rising sea level that floods homes and contaminates drinking water. Islanders rely on fishing to survive, but ocean acidification and rising water temperatures are killing off sea life.

“Why is God giving a blessing to America? Why not Kiribati too?” Timeon asks.

He tries out his new version of the US anthem in his raspy voice.

“God Bless America.. and us too.” He bursts out laughing. “God bless the whole world.”

Timeon didn’t understand or acknowledge climate change when he was younger, but in the 1980s, he started noticing changes that his traditional knowledge of the land and ocean couldn’t account for. Ancient beliefs and customs were called into question. There was unprecedented flooding, killing trees and crops. The land eroded over the years, under siege from both sides of the narrow island. The road had to be moved inland three times, before they built a seawall. The community meeting house, the maneaba, always has to be built in the centre of the village. But now it sits on one side off the island. The rest of the land is simply gone, claimed by the sea.

Scientists say the global sea level rise is caused by two main factors: water expanding as it warms, and large-scale melting of glaciers and polar ice caps. Modeling from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) found that it would rise at an accelerated rate this century. Timeon can measure the sea level by other means.

“When I first got married I lived over on that side, in my wife’s parents house. Now, the place where we lived is in the sea right now,” he says.

“No more,” he adds in English.

It’s a bittersweet trip to the village of Taborio in North Tarawa for Toani Benson, an accounting teacher turned climate activist. He attended the Catholic boarding school here as a child, and a group of nuns, some of his old teachers, comes out to greet us. They mock scold him as he makes them laugh. It’s school holidays now, so they sit in their buia, weaving baskets out of palm leaves to sell at the market, playing volleyball in the shade of the coconut trees.

But Taborio is not the same place it used to be. As we hop off the boat and wade through crystal clear turquoise water he points to a patch of beach as the waves wash over it.

“When we were kids we used to go camping here, in this spot. Now…”

His voice trails off as he waves his hand and shrugs, gesturing at the abandoned house teetering on the edge of what used to be a beach, above exposed tree roots and dead coral.

There’s no need to finish the sentence describing the impacts of climate change on his childhood home. What’s the point, when the evidence is all around?

But you don’t have to look much harder to see that the people of Kiribati, the I-Kiribati, are not giving up on their island. They’re on the frontline, and they’re fighting back.

Toani is a member of a group of young Pacific Islanders from 15 nations campaigning for the survival of their homes. They call themselves the Pacific Climate Warriors.

"We are not drowning, we are fighting” is their war cry, and they travel the world, sharing stories of their culture and protesting at new mine sites. They want the world to know that they are not passive victims of climate change.

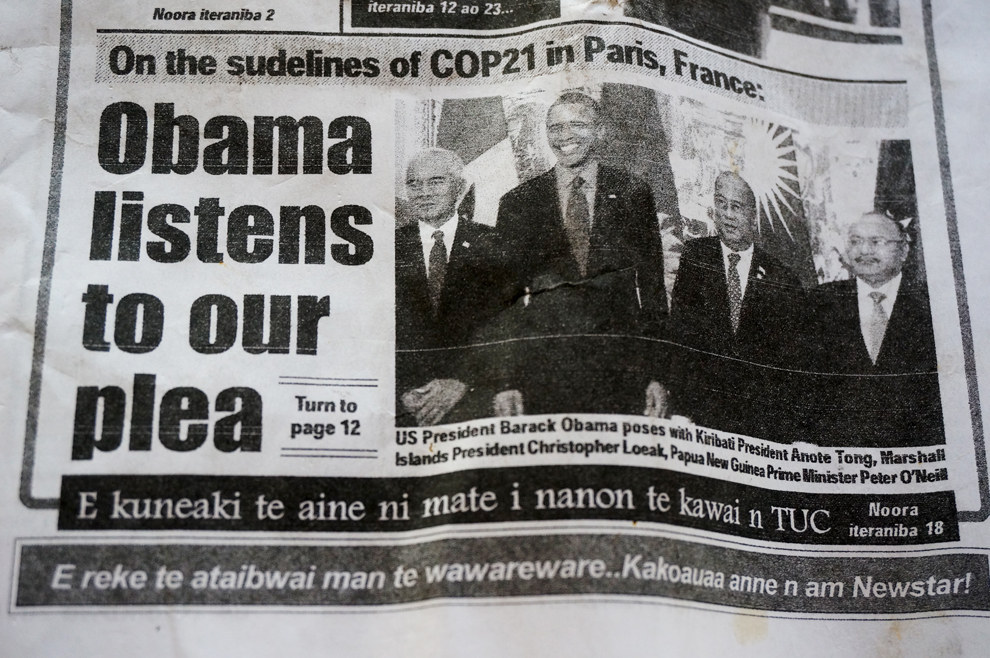

15,000 km from home, Kiribati president Anote Tong has also been fighting. Along with other Pacific leaders attending the COP21 talks in Paris Tong argued for the world to commit to a limit on global warming of 1.5 degrees Celsius , repeating the mantra “1.5 to stay alive”.

Marshall Islands foreign minister Tony De Brum spearheaded the Coalition of High Ambition and by the end of the talks, 195 countries agreed to hold the increase in temperature to well below 2 degrees, and to “pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees.”

In addition, developed countries promised to provide $100 billion for a fund to help vulnerable nations suffering loss and damage. It was cautiously welcomed by Tong, who stressed that agreements had to be followed by action.

"There was very clear acknowledgement of the special circumstances of the most vulnerable countries on the frontline of climate change,” he told the ABC.

"We are hoping that in spite of the lack of clarity in the wording, there is this very clear understanding that if it comes to building up climate resilience and adaptation and just recovery, countries that made a commitment will deliver," he said.

In Betio, in the western corner of South Tarawa, a rusty fishing boat smashed into a seawall by the waves is an arresting visual reminder of the danger posed by the high tides, which are becoming more frequent and increasing in intensity.

The force of the collision toppled a coconut tree, that now acts as a bridge for the children of Betio, who walk the plank to get to their very own rusty pirate ship.

“Hey! Hello! Hey!” the kids say in a grinning mass, jostling around me.

Do you remember the floods?

"Yes" they say, in ramshackle unison.

Were you scared?

“Yes,” they reply. “The waves came right up.”

They know what climate change is too. The world is getting hotter, one declares confidently.

Pacific Islanders have historically been able to adapt to extreme weather conditions and life on the constantly shifting coral atolls. But according to scientists, these children will have to deal with unprecedented turmoil caused by human-induced climate change, with the possibility that their island home could become uninhabitable.

On the outer islands, the impacts of climate change are obvious, but the situation is more complicated in South Tarawa. Home to 50,000 people, half the population of the entire nation, some parts of the island have a population density comparable to Tokyo or Hong Kong. Stray dogs sniff at rubbish strewn alongside the dusty main road. Homes are cobbled together with a mix of the traditional and the new.

Rapid urbanisation, lack of proper sanitation, high unemployment and extensive poverty for the developing nation are issues compounded by climate change.

Australia, the largest neighbour in the region, provides the most aid to Kiribati. Sitting in his office in Bairiki, acting Australian High Commissioner Michael Hunt believes it’s a challenging place for foreign aid.

“There are developmental problems here, immediate pressing issues that do need to be addressed before climate change,” he says.

He sees the biggest challenge for the country as what he calls a “poverty of opportunity” for the burgeoning young population, intensified by internal migration, as more people move to Tarawa from the outer islands looking for work.

“When the young generation graduate from education, there’s the possibility of internal conflict arising from unfulfilled expectations.”

Most money comes in from fishing revenue, and money being sent back home from citizens working overseas. The private sector is small, and as a result the government’s public finances are limited. The government’s recurrent budget is $120 million, about the same as that of a local council in Australia. It’s hard enough to maintain education, social services and infrastructure, without the added costs of rebuilding homes after vicious storms and flooding, which now strike more than three times a year.

High tides spilled over the seawall and into people's houses in June.

The rising ocean tides contaminate drinking water. Most residents have wells to pump freshwater out from a fragile underground lens of water that sits just below the surface. But now, they’re finding the water is salty, and making them sick. There are some community rainwater tanks, but not enough, and they cost about the same as a yearly wage for the average I-Kiribati. The water board pumps water out from the main reservoir that sits just under the Bonriki Airport tarmac, but only for a couple of hours a day. People have hacked the pipes to redirect the water to their own homes.

Simon Donner, associate professor of climatology at the University of British Columbia has studied the way Kiribati has been dealing with the rising sea level.

“You shouldn’t look at every flooding event that you see photos of and say ‘Aha! That’s climate change!’ because often the reason there is a lot of damage is that Tarawa is overcrowded and people move into vulnerable shoreline that no-one would have lived in 100 years ago because they knew better not to do it. But now because of overcrowding, people are living in very vulnerable locations - which is the same thing you could say in many crowded megacities in the world.”

The Kiribati government has been hard at work educating people about climate change. Claire Anterea works with the Kiribati Adaptation Program (KAP), traveling to communities on the outer islands to teach people how to cope with what’s happening now, and what’s to come. People tell her that the sun must be coming closer to earth.

“We do an action to explain global warming to people. We tell someone to smoke a cigarette and then we cover him with a mosquito net. What do you see? We ask them, and they see the smoke. And then we cover him with a blanket. When we take it off the man is sweating and coughing. We explain that is what is happening to the planet, from all the factories and the greenhouse gases becoming trapped in the atmosphere, and we explain that the ice is melting on land and flowing into the sea, which contributes to the rise in sea level,” she says.

Adaptation is the next big challenge for the Pacific Island nations. Government projects like KAP work to plant mangroves to protect the coastline, build seawalls to protect their homes, and teach people how to plant their own subsistence crops in difficult growing conditions.

Having convinced the world that they are suffering the impacts of climate change, they now have to secure the funds and figure out how to manage them.

Driving around the shark-fin shaped atoll of Tarawa, evidence of foreign aid is everywhere. How do you know that Australia is building a flood-resistant road for Kiribati? Don’t worry, there’s a big AusAid sign right next to it telling you. Every solar panel on domestic rooftops is emblazoned with the logo “With love from Taiwan.”

Funds from big polluting countries are necessary to help Kiribati adapt to climate change, but Professor Donner says they are often misspent.

“What’s happening in Kiribati shows just how hard adaptation is. The real day-to-day slog of trying to figure out what are good solutions we can afford and what are good solutions that we have the capacity to maintain. There are a lot of good intentions designed to help Kiribati adapt, but often they don’t work because of the need to rely on outside money and expertise. People come in without a great idea of what people in Kiribati are interested in and able to do.”

Pelenise Alofa knows the frustration of aid implementation all too well. She wants donors to work more closely with communities, describing the bureaucratic barriers and tangled network of foreign contractors and consultants that must be paid before anything is built.

“When I hear that the countries at COP have put aside aid money for developing countries, I ask myself, how much money will reach my people? When I say my people I mean the person right there on the ground, the person who will be collecting that water from the water tank. How much of that will reach them?”

But she has hope for the future, excited that a new generation of I-Kiribati studying at university are becoming qualified to become advisers to the government on climate change and aid implementation.

“Our young people say, we’re not moving, we will fight to stay here. Climate change has opened another door of opportunities. Before, nobody was thinking about renewable energy but now" - she claps her hands with excitement - “Ok! Let’s go and study climate change, renewable energy and water management and maybe help our people to adapt.”

Despite Kiribati's valiant efforts at adaptation, the nation's president Anote Tong has already prepared the the worst case scenario. In 2014 Kiribati's government purchased 5,000 acres of land on Fiji's Vanua Levu incase the I-Kiribati become some of the world’s first climate refugees: a policy Tong calls “migration with dignity”.

Everyone knows about the plan, but there are mixed feelings. Some people, sick of constantly repairing sea walls and frustrated by the lack of opportunities, are impatient to leave for Fiji, and angry it hasn’t happened yet. Others are more cautious.

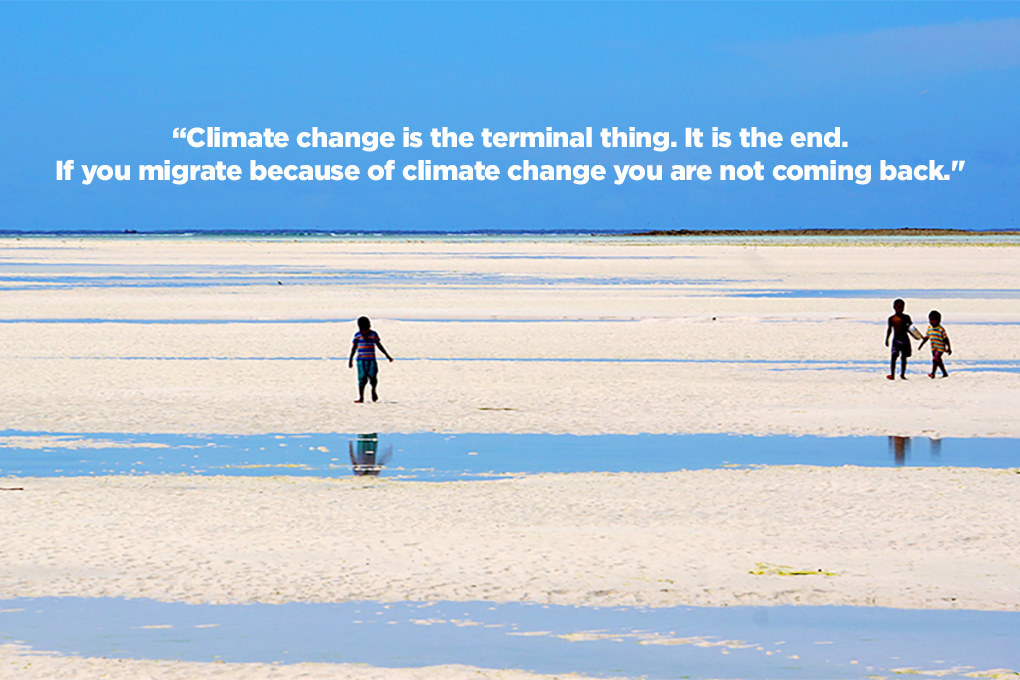

Pelenise Alofa believes there’s a world of difference between people wanting to migrate to look for jobs, and becoming climate refugees, unable to move back home.

“Climate change is the terminal thing. It is the end. If you migrate because of climate change you are not coming back. But if you go for other economic reasons, you can come back. I think our people want to migrate because they want to see they world, but it’s totally different to migrate because there is no more Kiribati,” she says.

“Our Pacific people have never really left home. When they migrate they can always come home to their own land, but when you talk about a refugee, a refugee is a person whose rights have been taken away. As long as Kiribati is here, people will stay here."

Claire Anterea recalls seeing people eating out of the trash and orphans alone on the street in her travels to India and South Africa. She fears the same for Kiribati's people if they are forced to resettle in countries where it is impossible to survive without money.

“We already have our own peaceful place here. There are no guns, no people shooting each other on the street. Our standard of living is different but we are rich in families and values. Here, we can live without money. If you don’t have money you can go fishing, or you can pick breadfruit from the tree, or eat taro, or coconut or bananas.”

Kiribati is playing its part, shifting to renewable energy and creating protected marine zones for ocean biodiversity, now she asks the world to play theirs.

"I would say to the world to keep working hard to save our islands. We understand that countries like Australia have people who need to work, but we are on the frontline. We are only two metres above sea level and if people are willing to take a step out of their own comfort zone so we do not have to leave our land, that would be our dream. It's time to do it now. They talk about economy, but we talk about survival."

As the sky and ocean conspire to put on another spectacular sunset, young men wade out into the lagoon with a fishing net to catch dinner as teenagers kick a soccer ball around on the local sports ground. The voice of the bingo caller echoes out of the meeting house.

Over a plate of fried chicken wings in a low key Chinese restaurant run by the president's daughter, two young men are discussing the future.

“One day there will be a seawall all the way around Tarawa,” one says with a smile, sipping from a can of Australian beer.

“Maybe it will bring tourists to Kiribati, like the Great Wall of China,” the other counters.

They burst into laughter.

“Yes! The Great Seawall of Tarawa!” He leans back on his plastic chair and imagines it. “That would be good, I think.”

Down the road, young men and women are dressed up at a graduation ceremony from a course run by the Mormon church. Between the benediction and speeches from graduating students, the words of one hymn in particular stand out.

We will not retreat, though our numbers may be few, When compared with the opposite host in view; But an unseen power will aid me and you.

The name of the hymn is “Let Us All Press On”. As the people of Kiribati wait for the rest of the world to drastically curtail carbon emissions and stop the ocean from claiming their island, for now, this is all they can do.