WASHINGTON — After six years of promising to repeal Obamacare, congressional Republicans are finally in a position to do so. But now they are heading home to their districts for recess, with only vague details of how they’re going to move forward.

“We’re putting ourselves at risk to a certain extent” by seeking to overhaul the health care law, President Donald Trump warned congressional Republicans gathered in Philadelphia last month.

Now Republicans find themselves dealing with those consequences, facing pressure from constituents, their base, and liberal groups to hold town halls, with just a broad set of principles and guidelines to point to on how they could, eventually, repeal Obamacare. And with the voices on all sides getting louder, the simple message of “repeal and replace” isn’t going to work much longer.

“What we can’t do is continue to talk about goals without giving specifics to the American people and I think that’s part of the frustration that you see,” Rep. Mark Meadows, who chairs the conservative House Freedom Caucus, said at a BuzzFeed Brews event this week, noting that his office got “about 1,300 this month,’ up from an average of 150.

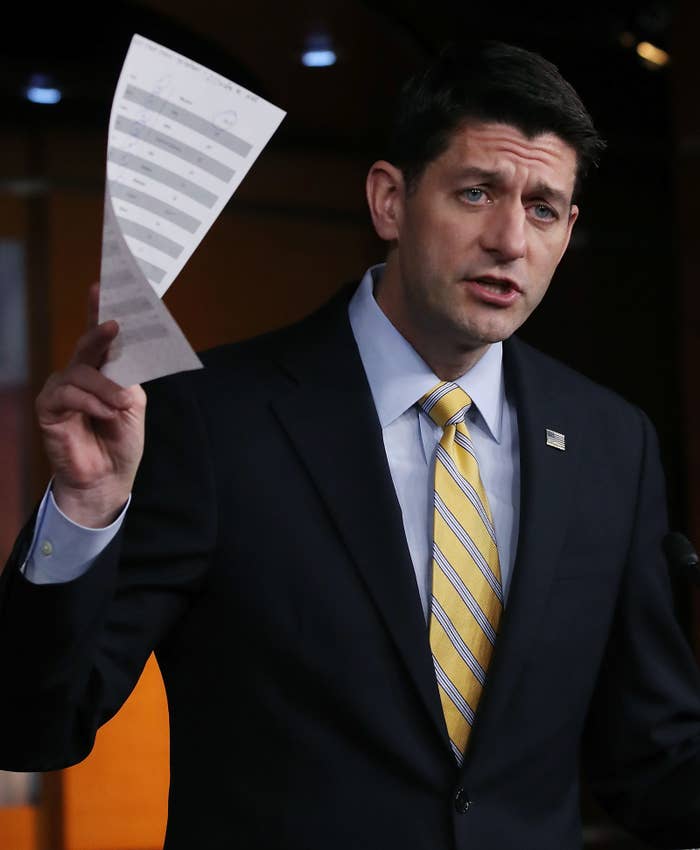

House Speaker Paul Ryan, on Thursday, told reporters they would roll out a plan to repeal and replace the much-maligned health care law after the recess, which ends on Feb. 26. That can’t come soon enough for some members.

“I can’t constantly go home and say I’m against this thing — what are we for?” Pennsylvania Rep. Scott Perry said at the BuzzFeed Brews event, blaming Republicans’ reticence to pass piecemeal health care bills out of committee in recent years to at least give them something to go off of. “I mean I co-sponsor bills and talk about the principles but until you put that in legislative language, you can’t go out and tell people this is what we would like to change … and this is how we’re going to do it.”

Until then, Republicans are stuck talking about the principles they agree on and explaining why things are taking so long. And that’s where things can get tricky.

“Until I got here eight years ago, I didn’t understand the speed of this place, which is glacial,” said Tennessee Rep. Phil Roe. “I think that’s not necessarily bad,” he added, “especially on something as big as this health care issue.”

House Republicans regularly gripe about the Senate and it’s complicated procedures that make any substantive policy changes take ages (“We play rugby; they play golf,” Ryan has said). But explaining that to constituents unfamiliar with the process who want answers now isn’t easy.

“It’s a challenge. It’s a challenge because the legislative process is much more difficult than people think it is, even if you control everything,” said Ohio Rep. Pat Tiberi, who chairs the Subcommittee on Health. “And no one quite understands the 60-vote threshold in the Senate, so it is a communication challenge, there’s no question about that.”

The slow process has Meadows and other members of the House Freedom Caucus calling for Republicans in the House to at least start debating something, arguing that it’s better to make changes to a plan that’s out there than to continue debating broad principles with nothing to show for it.

“We believe we need to start the debate on what actually goes into a replacement plan. Not about the goals, not about anything else, but let’s start debating it. ... Did we act quick enough? I don’t think so. I would have loved to have done it on January 20, but at this point hopefully we’ll do it in the next 30 days,” he said.

But Republicans are also facing another communications challenge — how to deal with an increasingly vocal group of liberals who have already turned several Republican town halls into circuses. How do you reason through what Republicans are trying to do with health care in that setting?

“You can’t. It’s impossible,” said Roe. “So you just have to sort of play it out over time and show people results. If we do what we say we’re going to do, which is hopefully provide better health insurance coverage for more people, we’ll be fine. If we don’t do that, we’ll have problems in 2018.”

The National Republican Congressional Committee, the House Republican campaign arm, is taking a hands off approach to how members handle those town halls — or if they do them at all. The committee has talked to more than 80 offices one-on-one to address specific concerns. Some members are scheduling in-person town halls, while others are doing virtual town halls – either on the radio, on the phone, or over Facebook – where they have more control over the questions.

“I’m not interested in being baited into an event so an outside group can then hijack it and make a spectacle out of it. That doesn’t help my constituents get heard at all,” said New Jersey GOP Rep. Tom MacArthur, who was asked during his tele-town hall this week why he had no in-person events scheduled.

In the meantime, Republicans on key committees and in competitive districts are getting some help. American Action Network has spent $6 million already this year on various forms of advertising touting Republican solutions on health care.

“Our job is not to provide cover; our job is to communicate the Republican plan to key constituencies. And that's what we've spent over $6 million doing,” said AAN president Corry Bliss.

But for now, members cannot point to a definitive plan accepted by all Republicans. They can point to the principles, as AAN does, or one of the myriad of plans put out there by members of the conference, none of which are likely to be accepted in their entirety.

“It’s important to note that we are in week five of this Congress, and the first three weeks of this Congress we didn’t even have a president. We didn’t have a Health and Human Services Secretary until this week,” said Ohio Rep. Steve Stivers, who chairs the House Republican campaign arm.

And until the recess is over, they won’t have a concrete piece of legislation to point to. Until then, they’ll do what they can.

“You try,” Tiberi said. “You continue to try.”