Crime stories of murderous husbands or kids killing their parents resonate because they combine transgression (I can’t believe they did that!) and relatability (what if that happened to me?). Serial killers, on the other hand, fascinate the public precisely because their horrific acts seem monstrously outside of human comprehension. The higher their body count, it seems, the more notorious they become.

Richard Ramirez is one of the most well-known serial killers in history. His violent crime spree — including murders, sexual assaults, child abductions, and home invasions — threw California into a state of panic in the mid-eighties.

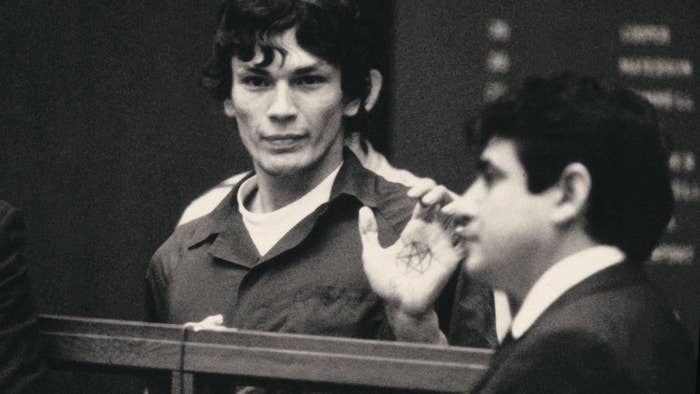

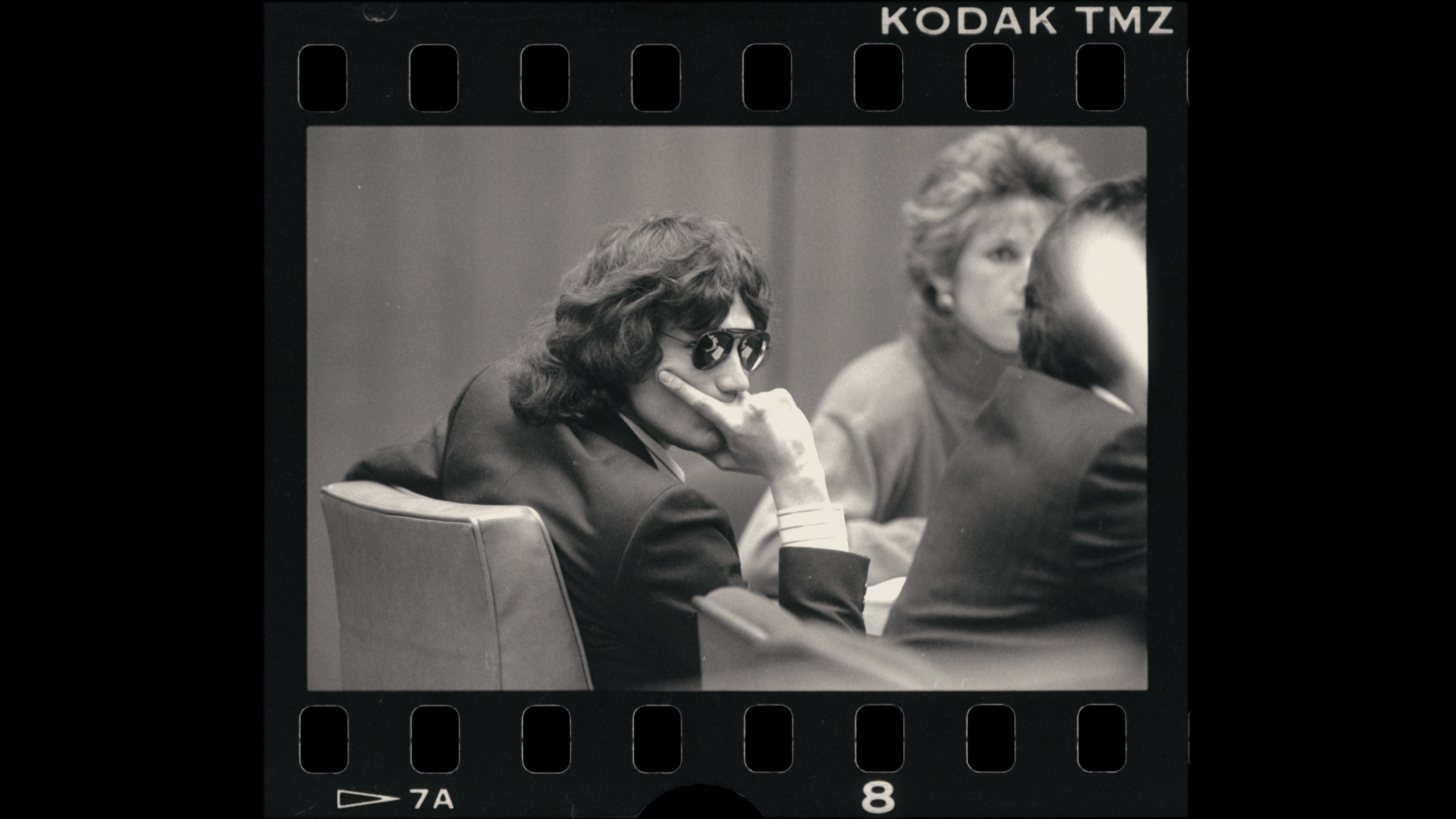

He was eventually tried and convicted of 13 murders, five attempted murders, 11 sexual assaults, and 14 burglaries, not including his victims who were minors. Pentagrams he drew at his murder scenes added a Satanic edge to his persona, as did his striking looks and faux–deep philosophizing about evil. His trial captivated the nation and he played up a depraved persona to cameras — wearing sunglasses to his trial and shouting “Hail Satan!” He even attracted groupies.

So it’s not surprising that he’s now the subject of a new Netflix docuseries: Night Stalker: The Hunt for a Serial Killer. Director Tiller Russell said he didn’t want his docuseries to “glamorize” the murderer — and it’s true that it doesn’t follow the well-trod ground of humanizing or explaining the killer, like the Oscar-winning Aileen Wuornos biopic Monster or the recent plethora of Ted Bundy documentaries and movies.

Ramirez remains a spectral presence in the series, appearing mostly through voiceovers. But the documentary doesn’t provide much insight into anything else beyond the crimes, like Los Angeles in the ’80s, policing failures, or even the ongoing cultural fascination with serial killers. Instead, it’s a glorified cop procedural that sensationalizes Ramirez’s spree in lurid detail.

As its subtitle announces, The Hunt for a Serial Killer is not the usual exploration of criminal psychology. Instead it’s a play-by-play of how California law enforcement (and, we later learn, the public) hunted Ramirez down as he terrorized Los Angeles, and later San Francisco, over several months in 1985.

The series largely centers around interviews with two detectives at the helm of the investigation: Gil Carrillo, a self-described former gang member who becomes the series’ most fleshed-out character, and Frank Salerno, who’d gained recognition for his work solving the Hillside Strangler case, another series of Los Angeles murders committed by two men in the late ’70s.

Unlike the Hillside Strangler, though, police didn’t initially connect the spate of rapes, murders, and child abductions as being the work of one person. His victims didn’t fit one type; they included older couples, young women, and children; some were murdered, others sexually assaulted. As the docuseries opens, we learn he murdered one woman and shot her roommate while escaping, abducted and sexually assaulted a 6-year-old girl, and brutally attacked two sisters in their eighties, raping one and killing the other.

While the spree is mostly recounted by Carrillo and Salerno and some reporters who were working at the time, the documentary also features interviews with the surviving victims of his crimes or their family members. A woman who had been sexually assaulted by Ramirez when she was 6 years old, for instance, offers gruesome and poignant details of her ordeal after being abducted from her bedroom one night.

But the victims’ and the families’ perspectives seem to be presented more for shock value than as a way of allowing them to reclaim their trauma. The plethora of gory crime scene photographs shown and reshown for creepy effect and the re-creations of rapes and murders often come off as gratuitous — deployed solely to heighten the dramatic stakes of the cat-and-mouse game between Ramirez and the police and media.

Carrillo is credited with pushing the investigation forward against all odds — including, at the very start, attempting to prove that the crimes were linked — amid rising public pressure as Ramirez’s mounting body count became more and more of a media story. Initially nicknamed “The Walk-In Killer," and "The Valley Intruder," he was finally branded the “Night Stalker” as his spree spread across Los Angeles’s mostly middle- and working-class Eastside communities. News footage of frightened Angelenos buying guns and taking self-defense classes further illustrates a climate of pervasive fear. (Even Carrillo’s family moved out of his home after Ramirez struck nearby.)

Adding to the panic and frenzy, word began to spread that the Night Stalker had made satanic references during his attacks (he told one surviving victim to swear to Satan, not swear to God), and drawn pentagrams on the walls in the crime scenes. The media — and docuseries — framed him as the embodiment of evil, almost supernatural. “This guy's gonna levitate right out of this room and scare the bejesus out of me,” said Carrillo, about his fears when he first interviewed him.

Yet Ramirez made numerous mistakes, and the police’s own multiple missteps helped him elude capture for months. Because of cross-division turf wars, a car that Ramirez used was left out in the hot sun and was fingerprinted so late that they lost crucial evidence and time. Dianne Feinstein, then the mayor of San Francisco, held a press conference about several murders the Night Stalker perpetrated in her city, leaking privileged information about shoe prints found at multiple scenes. Ramirez was watching the news and reportedly ditched the shoes that linked his crimes.

Most egregiously, because of supposed budget constraints, the LAPD decided to remove officers staking out a dentist’s office — one of the only leads they had — where Ramirez showed up soon after. The trail went cold again, and Ramirez committed more murders and assaults. None of these missteps are highlighted as a result of systemic issues or serious incompetence; instead, they become signs of random setbacks that the heroic cops — especially Carrillo — must fight against.

It was ultimately an informant who revealed Ramirez’s name to San Francisco detectives. (One cop fondly recalls threatening to punch that reluctant informant in order to get the name.) When San Francisco police released Ramirez’s picture, which got plastered on the cover of every newspaper and newscast, he became a walking public target. It was a passenger on a bus with the serial killer who ultimately alerted the police to his whereabouts, finally leading to his capture. As Ramirez attempted to flee, Angelenos surrounded him, beating him and holding him until a patrol officer stopped after seeing the gathered crowd. These moments are represented as part of a crescendo of justice finally being served.

There’s no comment, however, on the mob justice and vigilantism involved in Ramirez’s capture, or, for that matter, the potential police brutality against the informant. Or the irony of the series celebrating Carrillo’s role as a heroic Mexican American cop for his work in the ’80s, as the LAPD at the time was grappling with its institutionalized racism. More broadly, the focus on the hunt, and on Carrillo’s character arc, means the documentary loses steam after the capture, and glosses over the meaning of the cultural fascination with Ramirez.

The aftermath of the story and Ramirez’s trial is stuffed into the last episode. We see footage of him wearing sunglasses at his court appearances and claiming society just couldn’t understand him. We are told that he accrued groupies who flocked to his trial and wrote to him in jail. (One woman who talks about her close encounter with Ramirez in the documentary is already a meme for calling these groupies “the dumbest bitches ever.”)

Talking heads trot out tired ideas about criminal causation. “Practically all the things that could poison a child’s life were part of his life,” one reporter mentions; another notes that Ramirez’s father used to punish him by tying him to a cross in a cemetery overnight.

Carrillo notes in passing that Ramirez was actually a student of serial killers — both Charles Manson and the Hillside Strangler — and was seemingly courting celebrity through his crimes. He followed his own case closely on the news and was thrilled to know that Frank Salerno was one of the detectives on his case. He appeared to have tailored his crimes for infamy. But there’s no analysis of, say, the media’s commodification of criminality, or even what the sanctimonious moralism around the commercialization of crime means.

Instead, the series relies on rehashing clichéd ideas about evil to explain away why Ramirez did what he did.“There’s evil in that man,” says one court spectator. Despite its director's skepticism about glamorizing Ramirez, Night Stalker ultimately agrees that evil sells. ●