Zayd Dohrn still vividly remembers the most striking moment of his childhood. “Coming down the stairs in our fifth-floor walk-up in Harlem,” he told me from his living room in Chicago, “seeing these two guys leaning on a car, and knowing right away that they were federal agents.” His parents, on the run from the FBI, had schooled him on telltale signs that they were being watched.

“It had a nightmare quality,” the 44-year-old playwright and Northwestern University professor said. “Definitely a moment of realizing your life is going to change, and realizing that all the things you’d been worried about or been thinking about as a kid were actually happening.”

Dohrn is the son of Bernardine Dohrn and Bill Ayers, two of the most notorious, mediagenic leaders of a radical wing of the late ’60s New Left: the Weather Underground.

In Mother Country Radicals, his new podcast with Crooked Media, he chronicles the story of this now mostly forgotten group. Former community activists disenchanted with the limits of peaceful protest against police brutality and the Vietnam War, they sought nothing less than — as their founding statement put it — “the destruction of U.S. imperialism and the achievement of a classless world.” Black Panther leader Fred Hampton called them “mother country radicals,” or “white people in the mother country that are of the same type of things we are for.”

They pushed the boundaries of personal and political norms, making headlines for their “smash monogamy” mores and waging a “propaganda of the deed” campaign: bombings of symbolic edifices like the Capitol, the Pentagon, and the State Department.

An accidental explosion at the home of member Cathy Wilkerson in 1970 resulted in the deaths of three members and also destroyed the group’s legitimacy. Group leaders like Ayers, Dohrn, and Kathy Boudin, daughter of prominent labor lawyer Leonard Boudin, went into hiding.

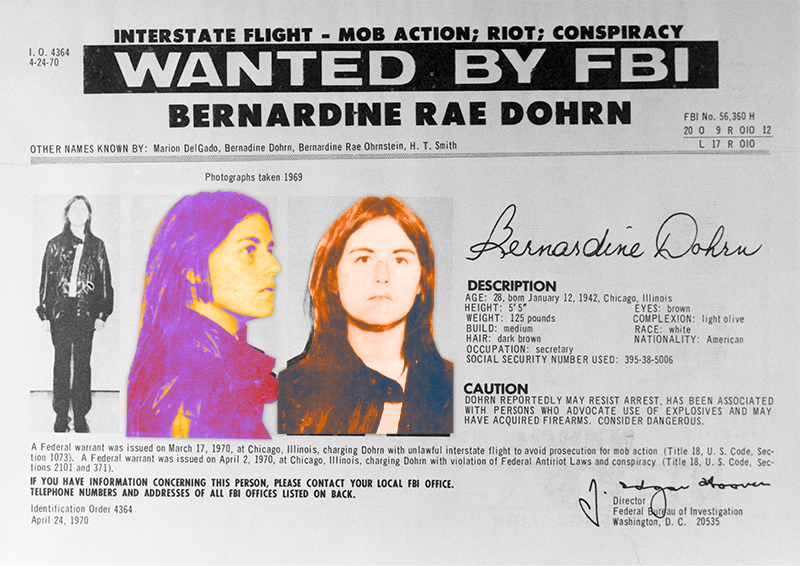

The FBI beamed wanted signs across TV screens, turning the members’ faces into emblems of white middle-class rage and the radicalization of America’s promising young women. J. Edgar Hoover called Dohrn “la Pasionaria of the lunatic left.” Yet, by 1977, after the end of the Vietnam War, the group had disbanded.

The Weather Underground has since been seen as something of a cult, and used by the right wing as exemplary of dangerous, misguided radicalism. Pulitzer Prize–winning Chicago Tribune columnist Mike Royko summed up one general view when he said in 1993: "They came from a background of being rich kids, where apparently tantrums would get them what they wanted. And they wanted immediate gratification and social change."

When Sarah Palin wanted to make Obama seem un-American in the 2008 election, she accused him of “palling around with terrorists,” referring to a fundraiser Bernardine Dohrn and Ayers held for him when he was a state senator.

“Every article you read was ‘unrepentant terrorist Bill Ayers,’” Zayd Dorhn recalled of the rekindled media spotlight. “It became an epithet attached to his name, it was incredibly surreal… Bill O’Reilly was camped outside our house in Chicago with a van.”

Dohrn found the media distortions and narrow focus on his father jarring. “It’s cultural amnesia,” he said. “My whole life I grew up with Bernardine being the central figure and the leader.” Yet, during the election scandal, the media referred to her “as [Ayers’s] wife,” Dohrn explained. “It’s crazy. That was never the dynamic.”

He also thinks the group’s history is more complicated than the prevailing narrative. In the series, he combines poignant personal memories and political postmortem in a kind of oral history of the ’60s underground. The podcast contextualizes the Weather Underground’s role in relation to groups like the Black Panthers and the Black Liberation Army.

But Dohrn is especially interested in grappling with his parents’ role in the organization, especially his mother, whom he views, as Angela Davis says in the podcast, as a kind of proto-intersectional feminist.

Bernardine Dohrn herself doesn’t like looking back, she told me. “I’ve been determined not to live in the past,” she said over Zoom from California. “And I think I’ve done a very good job of not living in the past, and to be involved in struggles that are happening now.”

Still, her son wanted to excavate lessons for activists about the challenges — and problems — of coalition building on the left. “There were things, obviously, that I had to overcome my own reluctance to touch — ‘sex lives of the Weather Underground’ — as the son, how deep into this do I want to go,” he half-joked. But he felt “a responsibility,” even when it came to “faults and shortcomings,” to grapple with them. “I owed it to myself, the wider world, the movement.”

The Weather Underground’s media-ready exploits have been amply chronicled. There was a 1976 Emile de Antonio documentary, Underground, filmed when the group was still in hiding. A 2002 Academy Award–nominated documentary, The Weather Underground, which included interviews with Bernardine Dohrn and Ayers, looked at the group through a broader historical lens.

In the late ’90s and early aughts, there was a slew of memoirs by former group members like Ayers, Wilkerson, and arguably the most skeptical, Jonathan Lerner, who offered a queer perspective. More sober recent histories, like Bryan Burrough’s Days of Rage, have been partly based on newly declassified FBI documents.

But neither Bernardine Dohrn nor Boudin ever wrote a memoir. Zayd wanted to get them on the record; his mother was nearing octogenarian status, and Boudin had cancer (she died earlier this year). “I started to feel like I had a chance to ask some questions I’d always had,” Zayd said, “and talk to people in a frank way — preserve those voices for my own family, my daughters, and posterity.”

The podcast begins its story in the mid ’60s, when the eventual members of the Weather Underground, including leaders like Dohrn and Boudin, were energized by the civil rights movement.

Dohrn grew up in suburban Milwaukee, the daughter of a furniture store credit manager, and went on to study political science at the University of Chicago before heading to law school. The sense of community in activism inspired her, she says, sharing a story in the podcast about Muhammad Ali showing up at a slumlord eviction strike in Chicago. Sheriffs were throwing tenants’ belongings on the street, and Ali started picking things up and putting them back in the houses. “Instantly, everybody … goes forward and picks up something and follows him in the building and takes it up,” she recalled.

Boudin was an activist for service workers at Bryn Mawr College, where she was valedictorian of her class. She went on to Case Western Reserve law school in Cleveland, where she started working with low-income mothers. In a 2001 interview with the New Yorker, she talked about the sense of hope activism gave her. “It was thrilling,” she explained. “I felt like I was learning about the realities of class, of poverty. It was the discovery that there was a whole other world that I was living next to, part of, and didn’t really know about.”

Throughout the later ’60s, Boudin, Dohrn, and Ayers, a University of Michigan student and the son of a prominent Chicago CEO, all in their 20s, became involved with Students for a Democratic Society, then the largest organization of leftist students. It grew bigger than ever thanks to increasing public opposition to the Vietnam War.

“I knew that I was fucking up.” She laughed. “I knew I wasn’t doing it all right.”

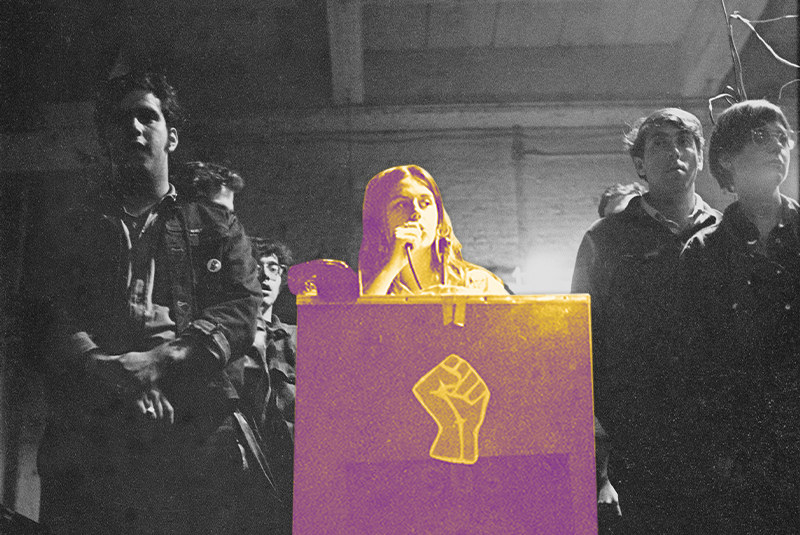

Dohrn, the group’s national secretary, became a nationally known face of the New Left. She’s sometimes remembered as a symbol of counterculture chic, once posing for a Richard Avedon poster in a trademark leather miniskirt. Network media seemed to love the color the New Left provided, and the SDS garnered plenty of coverage.

Long before left infighting and factionalism became social media fodder, student activism was rife with internecine wars. There were struggles about how to bring together anti-imperialist, anti-racist, and pro-worker politics, and to some degree, gender analysis.

Dohrn was trying to locate herself amid the factions. “I made decisions,” she told me, about what to address and how. In one talk at Yale, for instance, she said she faced a crowd of all men and “convinced them by the end that the war was terrible and they had to do more than just not fight the war, and disrupt the war machine.”

But a battle grew in SDS between its Progressive Labor Party and Dohrn’s Revolutionary Youth Movement faction for control of the group, and it came to a head at the 1969 SDS convention in Chicago. Dohrn and Boudin asked Black Panther member Chaka Walls to talk to the crowd. “We believe in the freedom of love, in pussy power,” he said. When some in the crowd reacted negatively to this characterization of women’s contributions to the revolution, Walls responded, “We’ve got some puritans in the crowd. Superman was a punk because he never tried to fuck Lois Lane.”

Attendees protested the “chauvinism.” The next day Dohrn, Boudin, and other women members staged a walkout and took over SDS.

Looking back at her efforts to bring together campaigns against racism, imperialism, and misogyny, she said, “There was no space in my environment — it certainly took me a long time. I give a lot of credit to the social movements, coming up with the word 'intersectionality.'”

She learned as she went, “trying not to let the contradictions tear apart the joy of being in the struggle,” she recalled. “But that being said, I knew that I was fucking up.” She laughed. “I knew I wasn’t doing it all right.”

Ultimately, Dohrn and Boudin’s walkout helped spark a splinter faction, the Weathermen, named after Bob Dylan's refrain: “You don't need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.”

In retrospect, the decision to name themselves after a song lyric written by America’s most lauded suburban white bard is telling, because the Weathermen’s actions often came off like a performance art project deconstructing middle-class whiteness: a mix of childish zest, appropriated Black vernacular, and sometimes cringey fantasies about revolution.

As Bryan Burrough chronicles in Days of Rage, they had essentialist ideas about working-class people being “more tough” and less bourgeois, and sought to recruit them into their movement. They took over classrooms at a community college in Detroit during exams and “lectured the thirty or so confused students on the evils of racism and imperialism,” he writes. In Pittsburgh, 26 Weatherwomen “stormed the halls of South Hills High School, waving a North Vietnamese flag, tossing leaflets, and … lifting their skirts and exposing their breasts.”

They started training for what was later known as “Days of Rage” demonstrating against the arrest of protesters at the ’68 Democratic National Convention, including New Left leader (and later Jane Fonda’s husband) Tom Hayden. “We really barely had any models,” Ayers says in the podcast. “So we began to do things like learn how to do karate and learn how to shoot pistols and learn how to make smoke bombs and learn how to make dynamite bombs.”

They expected thousands of students to show up at Chicago's Lincoln Park, but only about 200 did. Together, the group smashed windows and attacked a draft induction center. By then, 21-year-old Fred Hampton called the group “Custeristic.” “We think these people may be sincere but they’re misguided,” he said. “They’re muddleheads and they’re scatterbrains.”

They tried to leave behind cultural norms: “So much experimentation with sex, sex with women, sex with men, sex in orgies,” Boudin says in the podcast. Jonathan Lerner said the sexual experiments were basically for the men: “For me, it was sort of liberating, because I got a chance to have sex with some of the men I was after,” he told Burrough. “I have a memory of several women who came out as lesbians having their first sex with women, and it was weird because everyone was sitting around watching. … It was basically creepy.”

At a “wargasm” dance in a Black neighborhood in Detroit, Dohrn joked about the Manson murders, in words that have haunted her since: “Dig it. First they killed those pigs, then they ate dinner in the same room with them, they even shoved a fork into a victim's stomach! Wild!”

During the Obama-era controversy, she explained her Manson comments as an ironic joke, meant to highlight the amount of press coverage the true crime spectacle was getting. But in the podcast, she says she regrets the moment. “It was glorifying violence,” she admits. Tom Hayden was sitting in the front row and “came right up to me,” she remembers, asking “How could you say that?”

In retrospect, that embrace of violence seems like a consequence of hardening themselves, especially as white women, to leave behind aspects of femininity and bourgeois propriety that they felt were in service of capitalist inequality. After all, Dohrn had become radicalized through seeing white women’s reactions to the civil rights movement. “The men I would have expected to be hateful,” she says in the podcast, “but seeing the women being hateful was shocking to me.”

And there was a lot to unlearn. Members subjected each other to daylong “self-criticism” sessions, where they accused each other of not being revolutionary enough, of upholding the wrong values. “The more you get whipped, the more you feel like you’re becoming purified,” Boudin explains in the podcast.

“The models they were looking to were mostly these Communist, Chinese, Vietnamese, Cuban models, and those models had a very structural Marxist analysis,” Dohrn told me. “They resisted personal things — the criticism and self-criticism were an inverse of that. The whole point of them was to stamp out personal preference, personal history in service of a collective.”

Still, there was plenty of dissension within the group. “We had fought ourselves into a stalemate with several different factions internally,” Dohrn told me, explaining why she wasn’t present for the most infamous — and tragic — moment of the group, which came in New York in 1970.

Boudin, Wilkerson, and Diana Oughton were all in Wilkerson’s father’s townhouse in New Jersey, preparing explosives for a bombing at the Fort Dix military base that would “bring the war home.”

Dohrn wasn’t in touch with Boudin at that point. “I regret that I let go of arguing with a couple of collectives, one of which she was part of … the last few weeks before the townhouse exploded,” she told me.

When the bomb a colleague was making in the basement went off, it blew the house to smithereens.

When the bomb a colleague was making in the basement went off, it blew the house to smithereens. Three of their colleagues, including Oughton, Ayers’s former girlfriend, died.

Boudin was taking a shower; Wilkerson said she was ironing when the bomb went off.

To outsiders and the media, the blast seemed to mirror the group’s haphazard ideology. Boudin and Wilkerson emerged from the rubble and went into hiding. So did most of the leadership, and they became the Weather Underground.

Even in hiding, the group kept up their bombing campaign. They would announce the explosives to give people time to vacate, targeting police departments, the Pentagon, and other symbols of the American law enforcement apparatus. “We've known that our job is to lead white kids into armed revolution,” says a determined young Bernardine in her first communique from hiding.

They hoped, Zayd Dohrn said, to divert the FBI and police’s attention from intense surveillance of the Panthers. It wasn’t necessarily effective. “Pulling attention from the Black Panthers is a worthy goal,” he says, “but it also brought down more attention.” Some of their high jinks, like breaking out counterculture drug guru Timothy Leary from prison, look especially random in retrospect, divorced from any coherent politics.

In 1974, in solidarity with recently arrested Angela Davis, the group bombed the Center for International Affairs at Harvard. Their subsequent bombing of the San Francisco Department of Health, Education, and Welfare was pegged to International Women’s Day, accompanied by demands for daycare, healthcare, and birth control. (Apart from the three group members killed in 1970, no one was ever hurt by a Weather Underground bomb.)

In the 1976 Emile de Antonio documentary, Dohrn says: “We’re a very small organization, relative to the task to be done.” But by then it was unclear which task she was referring to. It was like an all-leadership organization, with no actual members. And the new iteration of the group turned on Dohrn.

In the podcast, she talks about being subjected to one of the self-criticism sessions. “Not being radical enough,” she recalls of the accusations, “for not partnering up with Black organizations more than we did … that I was self-serving and privileged.” She pauses. “So it’s stripping away skin and, you know, bone, till you feel like you don’t know who you are. And maybe they’re right. It was devastating.”

Both Bernardine and Boudin resisted personal explanations for their actions and decisions, or, as Zayd puts it, reducing their motivations to “Freudian rebellion against the father.” (In one episode, Zayd asks his mother if she thinks her organizing was about addressing her own father’s racism. “That’s too psychological for me,” she says.) Yet he says of Boudin, “When I visited her in prison, I used to joke about it as being psychiatry sessions, ‘cause we would sit there across the table from each other and stare into each other's eyes in these three-hour super-intense conversations about what was going on in her mind.”

In the podcast, both Bernardine and Boudin are candid, acknowledging the role that ego and self-conception played in their underground years. Dohrn says that she continued to hide in part because she “just hated the idea of surrendering. It felt like waving the white flag. It felt like being a radical activist would become something I did once, but not who I was, and I was pretty tied up in that identity.”

“I gave myself a certain kind of importance in staying underground, which was to be a symbol of resistance to the ongoing oppression and racism of the government,” Boudin tells Dohrn. She felt it was her “essence…a white woman who’s willing to sacrifice her life in a sense to supporting Black people’s struggle.”

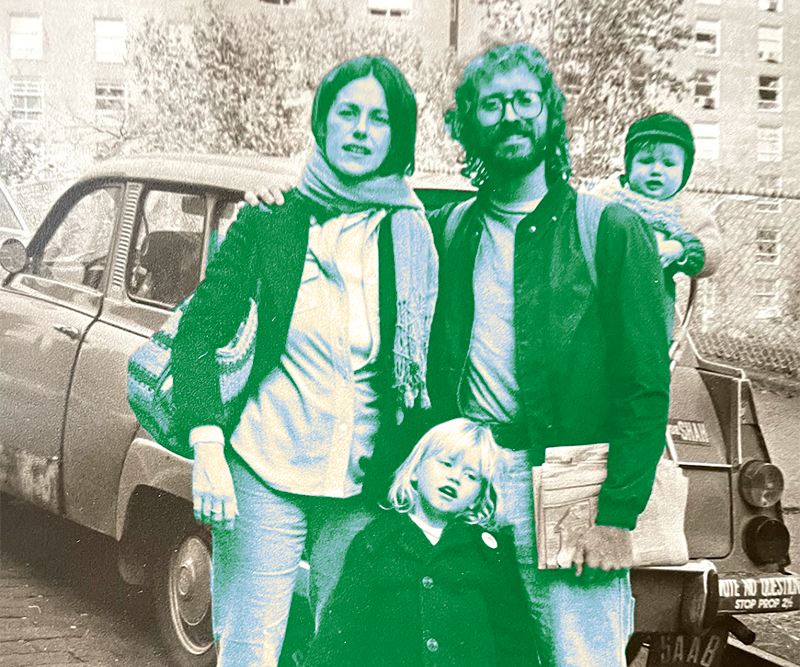

Dohrn and Ayers fell into their relationship underground; Zayd was born in 1977. His parents named him after Zayd Shakur, a murdered minister of information of the Black Panthers. During their time in hiding in New York, Zayd told me he knew his parents “by at least three names each and I had different names, although mostly they called me Z, because I didn’t have a birth certificate.”

It was raising him that made hiding increasingly impractical. Bernardine and Ayers turned themselves in to the police in 1980. By then, the FBI’s criminal behavior in its counterintelligence efforts to capture Weather Underground members led to all the charges against the group being dropped.

But the following year, Boudin, who had become a kind of outside assistant to the Black Liberation Army, was a getaway driver in a Brinks armored truck robbery that resulted in the deaths of a security guard and two officers. She received a prison sentence of 20 years to life.

After her arrest, her son, Chesa Boudin (who was recently recalled as San Francisco district attorney), went to live with the Dohrns. “They went back to my daycare,” Zayd said, “and reintroduced themselves to everybody, like ‘It’s in the papers, you all know what happened, let us try to explain where we were coming from and who we were.’”

Bernardine adds that Boudin would call for marathon phone sessions. “We had one wall phone, and there was a stool under it, the kids would talk to her,” she told me. “She was a known figure on the phone to their friends and to all of us.”

In the ’80s and ’90s, “this history was sort of forgotten,” Zayd says. “We just went about our lives.” Still, his mom refused to stand for the national anthem, which sometimes led to awkwardness at Little League games. Most Weather Underground members moved on to academia and the nonprofit world. Ayers became a professor of education at the University of Illinois. Bernardine became a law professor and juvenile court activist. Boudin became an activist for the formerly incarcerated and criminal justice reform, and after she was released from prison on parole, a professor at Columbia University. (The Black Liberation Army member Mutulu Shakur, also involved in the Brinks truck robbery and the stepfather of Tupac Shakur, is now seeking compassionate release.)

Of raising Chesa together with her friend behind bars, Bernardine told me, “We called it in our best times being ‘comadres.’” The word technically translates to comothers but is Spanish-language slang for best friends. But, she adds, “in fact there was tremendous amounts of sorrow, and pain and love, that carried it all the way through, and trust in each other.”

“I get tangled in exactly the kinds of questions we’re talking about, the complexity of: Is it this or is it that?”

“I’m writing a piece for Kathy’s memorial right now,” she said. She’s still grappling, at 80, with the lessons from that time and how to apply them. Looking back, she says ruefully, “Certainly when we were fugitives, we were stuck thinking not dialectically, not intersectionally. … Why didn’t we say the issues that are strangling the planet and turning us against each other are related?”

For her, solidarity is something complete, but difficult. “Solidarity implies you’re in it for the whole deal,” she said. “You have to stay in the whole conversation from beginning to end. You can’t just pick, ‘I like this group, and I’m going to do whatever they say.’ That’s not being a radical… you have to have your feet somewhere on the ground and be willing to be wrong. It’s messy.”

The children of these ’70s activists, including Kakuya Shakur, Assata Shakur’s daughter, who speaks out for the first time in the podcast, grapple with some of these questions in more concrete ways. “The cliché is … the hippie parents have the kid who wants to be a stockbroker,” Zayd told me. “That’s never been my experience, not of myself, not of my entire generation. You think of Chesa, me, Kakuya, Thai [Jones], all those people consider themselves to be radical whether they’re historians, writers, social workers, lawyers, activists, politicians. They all have differences with their parents, but I can't think of anyone who veered right.”

“It’s weird,” he said. “Growing up, I met Rosa Parks, Jesse Jackson — there was a world of people they knew and who they were connected to that was different than the other families.” Dohrn processes his past through his writing, including, now, the podcast. He views Chesa as the family’s true activist, though. “I joke with him and with my parents, that he’s the son they should’ve had,” he says. “They adopted him but he’s in many ways their proper heir.”

The two men lean on their family history in different ways. “It’s a cast of mind — I can’t quite summon the directness or activist nature he has,” Zayd says about his brother. “I get tangled in exactly the kinds of questions we’re talking about, the complexity of: Is it this or is it that?”

With Mother Country Radicals, he gives his own answer. ●