Cops who viewed Donald Trump as their law-and-order ally could now lose essential funding if the new president carries out his threat to crack down on cities that protect undocumented immigrants.

“Terrifying,” said New Haven police officer David Hartman. “This is something that’s terrifying.”

Their fear is rooted in a memo sent by the Department of Justice last summer to hundreds of law enforcement agencies, warning that they would be ineligible for large slices of federal funding if they violated a vaguely written law passed 20 years ago: Title 8, Section 1373 of United States Code.

Simply put, Section 1373 bars police departments and other government entities from withholding information about a person’s immigration status from federal officials. Scores of cities, like New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and New Haven, have countered Section 1373 with their own policies that aim to protect undocumented immigrants from the reach of federal deportation efforts.

No court has ruled on whether these so-called sanctuary cities are actually violating the law, and the Justice Department has not made a determination. The July memo didn’t clarify things, so officials in New Haven — a city on the forefront of sanctuary policies, according to Police Chief Anthony Campbell — weren’t worried at first.

“We understand that the federal government can say, ‘you’re a sanctuary city’ and turn the tap off.”

Then, in August, candidate Trump declared that he would “end sanctuary cities” within his first 100 days in office by barring them from federal funding. Three months later, he was elected president, and now, the July memo has taken on a new and ominous meaning. If Section 1373 is enforced, sanctuary cities stand to lose hundreds of millions of dollars in federal law enforcement grants — grants that “mean the world to us,” said Campbell.

“We understand that the federal government can say, ‘you’re a sanctuary city’ and turn the tap off,” Campbell said.

The bureaucracy of government funding is complicated, sprawling, and slow, and Trump’s administration would have to overcome a series of legal hurdles before it could dry out every bit of federal money to every sanctuary city. The hurdle is lowest, though, when it comes to more than $600 million in Justice Department funding. On the day he steps into office, Trump will immediately have the power to begin the process of draining police departments nationwide of many of the grants, subgrants, and other DOJ funds that they depend on for everything from hiring to training to equipment purchases.

“If those jurisdictions have not complied with the new policy by Inauguration Day, then our new president can throw the switch that I’ve created and turn off all their federal law enforcement funding,” Republican Rep. John Culberson of Texas, who orchestrated the DOJ policy change behind the July memo, told BuzzFeed News. “They can lose all their money at noon on Jan. 20.”

This would put the new president on a collision course with the law enforcement authorities he has vowed to protect. Trump, who has said “police are the most mistreated people in this country” and “we have to give power back to the police,” finds himself caught between his vow to rid the country of undocumented immigrants and his vow to strengthen the forces who maintain law and order.

Culberson usually doesn’t support the imposition of federal power into local policy. A vocal proponent of state’s rights, he recently proposed a bill that would give state officials “special standing in court” to challenge any federal regulation that they deem unconstitutional. Another bill he proposed would give governors the power to reject refugees sent to their state by the federal government. “It is unbelievable that the power for governors to choose what happens within their own state has been stripped by the federal government,” Culberson stated in a press release. His website puts his philosophy this way: “Simply put, John Culberson believes in ‘Letting Texans Run Texas.’”

His reverence for the 10th Amendment, however, stops at the borders of cities, counties, and states who, in his mind, “interfere in any way with the sharing of information regarding criminal illegal aliens in their custody.”

To those places, he said, “if you want federal money, follow federal law.”

“I’ve had my eye on this law for a long time,” said Culberson, who was elected in 2000. He gained the power to give Section 1373 some teeth when, in 2014, he was named chairman of the Commerce, Justice and Science Appropriations Subcommittee, which controls how much money the DOJ gets every year. Culberson reminded Attorney General Loretta Lynch of this in a February 2016 letter. “I expect your office to enforce Section 1373,” he wrote, “in the course of the upcoming 2016 grant application process.”

“If you want federal money, follow federal law.”

In his letter, he attached a list of cities, counties, and states that he claimed were violating this law — around 300 jurisdictions in all, compiled by the Center for Immigration Studies, a think tank dedicated to supporting immigration restrictions.

Five months later, the DOJ had implemented Culberson’s policy in at least three major grant programs: the State Criminal Alien Assistance Program (SCAAP), which gives around $200 million to local correctional agencies that house undocumented immigrants; the Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) program, which sends out more than $100 million, mostly to pay for new police hires; and the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant, the department’s largest, an annual pot of more than $300 million that gets doled out to local law enforcement agencies.

“This is just beginning,” Culberson said. “You have to start somewhere. I found a way to enforce that law, and I intend to expand this to every annual federal grant under my jurisdiction.”

For now, it is law enforcement agencies facing the most pressing questions over the future of their budgets and initiatives. Applications for Byrne and other DOJ grants open in January. The deadline to apply is March. The grants are announced in the summer. Yet departments remain in the dark over how the Justice Department’s new policy might apply to them.

“We don’t know,” said Hartman. “That’s the problem.”

DOJ officials declined to comment for this story, responding to BuzzFeed News’ questions with only a link to the new policy guidelines sent out in July.

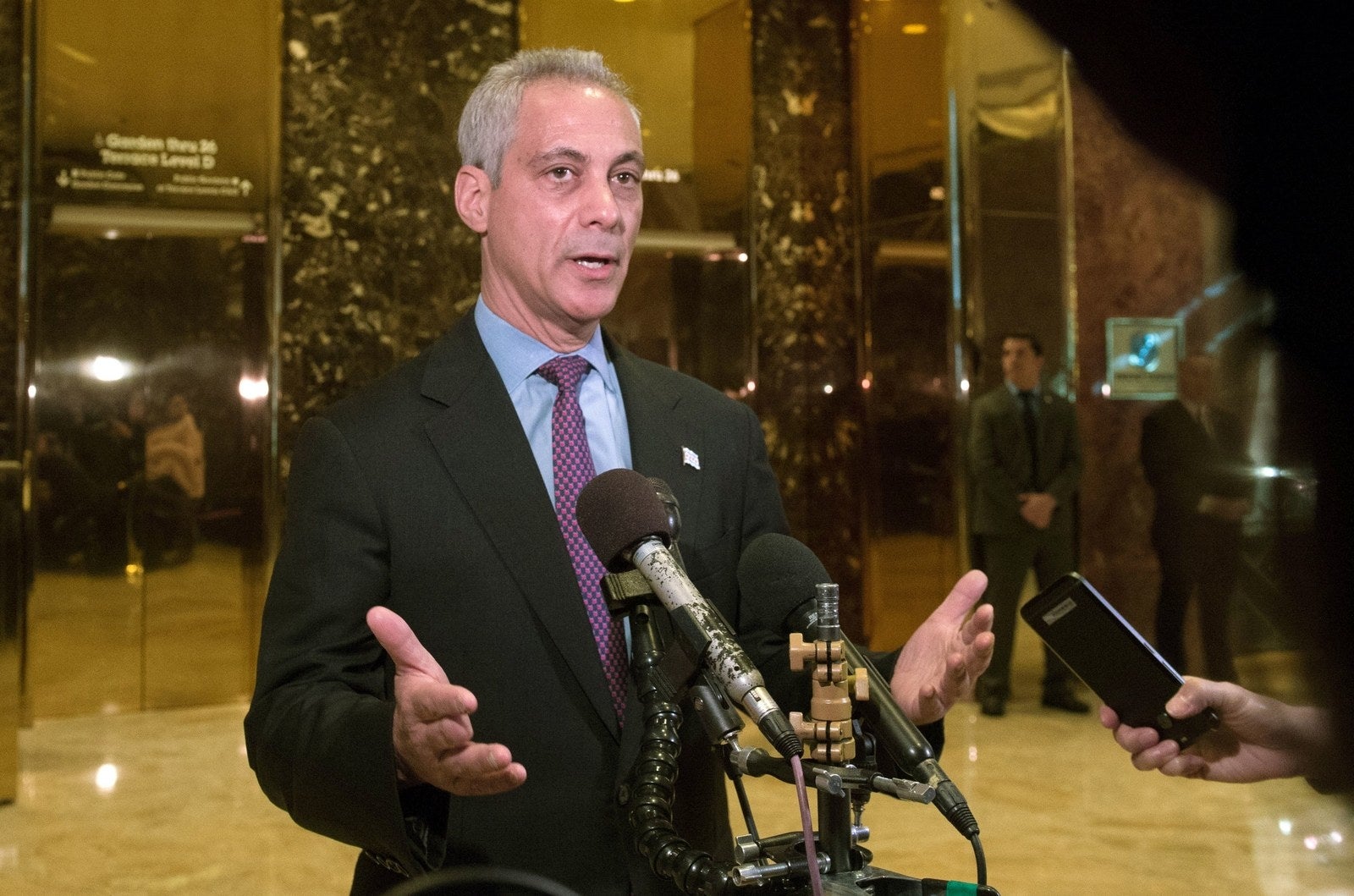

Rahm Emanuel said that Trump is bluffing about defunding sanctuary cities. The Chicago mayor served in the White House under two administrations, he reminded reporters during a December press conference, and based on that experience, he predicted that the incoming president “will not threaten all those cities.”

“When they look at all their priorities and the things they have to tackle, this is not where they are gonna go,” he said. “Because in governing, you have to make choices.”

A reporter asked: What’s the plan if Trump does go through with it?

“I’m not gonna get into hypotheticals because I don’t believe he’ll do it,” Emanuel shot back. “Because that will mean every major city in the United States will be targeted, and that is not what an administration will do.”

Many red states, Emanuel added, rely on the money brought into big blue cities, through property taxes and sales taxes, tourism and business. Residents of the Atlanta metropolitan area, for instance, account for more than half of Georgia's tax revenues. Would lawmakers really be willing to damage the “economic interests” of their own constituencies?

The Trump administration “will make a choice that this is not the battle they wanna take on because they have bigger fish to fry,” Emanuel said. “Just mark my words.”

His confidence seemed to conceal the stakes. The mayor had come to the press conference straight from a city council meeting in which he had warned that Chicago had to restructure its budget to avoid sweeping public sector cuts, including, by his estimate, a 20% reduction of the police force — a dangerous proposition for a city whose murder rate had increased by 58% from 2015 to 2016.

A recent review by the DOJ’s Office of the Inspector General calculated that the ten biggest cities and counties on Culberson’s list of 300 sanctuary jurisdictions received $1.7 billion in federal law enforcement funding over the last decade.

During Emanuel’s tenure, which began in the wake of the last recession, the Chicago Police Department has lost around 800 officers and civilian employees. Those cuts would have been deeper if not for federal funding. The city received $2.6 million in Byrne grants in 2016. Since 2011, its police department has received $15 million for 115 new hires through the COPS program.

Hundreds of police departments in cities big and small have relied on Justice Department funding to rebuild their ranks following the deep cuts of the recession years — a 2011 DOJ analysis found that 12,000 officers were laid off and 30,000 police positions went unfilled in the three years following the 2008 economic collapse.

The Los Angeles Police Department received $3.8 million in 2016 Byrne funding, and $3.1 million more in COPS grants to hire 25 officers. Oakland police received $1.9 million in COPS funding to hire 15 officers, and its county got $2.4 million in 2016 Byrne grants. Police in Hartford, Connecticut, have received $10.5 million in COPS grants since 2012 to hire 52 officers. Police in Wichita, Kansas, got $875,000 for new hires through COPS. Byrne grants in 2016 awarded police in Portland, Maine, $700,000; in Allentown, Pennsylvania, $100,000; and in Las Vegas $1.2 million. A recent review by the DOJ’s Office of the Inspector General calculated that the 10 biggest cities and counties on Culberson’s list of 300 sanctuary jurisdictions received $1.7 billion in federal law enforcement funding over the last decade.

“For most law enforcement agencies across the nation, federal funding is very significant,” said Rich Hoggan, chief financial officer for the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department. “We otherwise don’t have the money we need without the grants.”

On first glance, federal funding seems like a drop in the bucket of a police department’s budget. Of the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department’s $549 million in spending during the most recent fiscal year, just $13 million came from the federal government.

A closer look, though, shows that 93% of that $549 million covers the most basic, essential expenses: payroll, utilities, and vehicle and building maintenance. Hoggan compares this to the immovable expenses of a person’s life, like rent, food, insurance, and gasoline. That leaves just about $40 million for the department to spend on public safety initiatives, new equipment, new hires, and technological upgrades.

“We just don’t have a lot of discretionary dollars,” Hoggan said.

“We can try to go without the extra funding, but it makes things safer."

Most police department budgets look like this. And by these measures, federal funding can make up more than a quarter of a law enforcement agency’s actual “capital,” as Hoggan put it — the chunk of flexible money they can use to pay for things that could not otherwise fit into the budget, the things “we’re in need of” in any given year, said New Haven Police Chief Campbell.

New Haven police received $1.2 million in 2016 Byrne grants to pay for body cameras, Tasers, use-of-force training, and overtime for its depleted staff — “that’s an enormous sum of money,” Campbell said, noting that his department’s discretionary spending is around $4 million.

“The bulk of our budget, there’s no wiggle room,” said Campbell. “We can try to go without the extra funding, but it makes things safer. It lets us do our jobs better and fills the gaps for what we aren’t able to fit into our budget every year. When you see the impact of federal funding, it’s huge.”

Policing has gotten more expensive over the years. When Hartman began as a New Haven officer 22 years ago, “the most expensive thing a cop carried was a gun and a radio,” he said. These days, police departments aiming to keep up with technological developments accrue new, hefty expenses: mobile data terminals inside patrol cars, computerized crime statistical analysis, terabytes of data storage for all this new digital information, cloud software to hold the many hundreds of hours of body camera footage accumulating each day — all adding hundreds of thousands, sometimes millions, of dollars to the annual budget. “This is a different day and age, and everything costs a lot of money now,” Hartman said.

During the Obama administration, many of these new expenses were aimed at reducing excessive use of force. In New Haven, more than $1 million dollars of federal funding has paid for scores of Tasers, de-escalation training for officers, and the costs of sending command-level staff to travel the country to study the tactics of other departments. “They’ve helped us reduce the likelihood of deadly force,” Campbell said.

One of the models for implementing these new tactics is the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department, which saw police shootings decline by more than a third from 2010 to 2015. Over that stretch, the number of times an officer shot an unarmed suspect dropped from six to one.

Las Vegas police CFO Hoggan worries the department could be set back without federal funding, which helped pay for body cameras and training. It would be an especially unfair setback because, he said, his department does not consider Las Vegas a sanctuary city, even though it is cited on Culberson’s list. While the department’s policy does not explicitly prohibit officers from cooperating with federal immigration agents, Hoggan acknowledged that the new administration has the power to interpret the law as it pleases.

If Trump and Attorney General Jeff Sessions decide that Las Vegas is a sanctuary city, and if they decide to cut their federal funding, Hoggan said the department’s plan is simple: “We’re flat out saying you have the wrong guy.”

America’s criminal justice system is fragmented — a network of fiefdoms, each with its own laws, chains of command, constituencies, and rulers with the authority to make near-unilateral decisions. Police chiefs, appointed by mayors, can decide which laws to enforce strictly and which to turn a blind eye to. District Attorneys, elected by counties, can decide which types of criminals to throw the book at and which to go easy on. Police and prosecutors in San Francisco, for instance, have chosen to make arrests for weed possession a low priority, while the sheriff’s office in Maricopa County, Arizona, has chosen to make immigration law infractions a high priority.

“It’s a local system, and reform is based on the effort of local folks,” said Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart, who has pushed to reduce the number of people locked up in Chicago’s jail only because they could not afford bail. “The local level is where you’re gonna find the innovations.”

Obama has made strides in rolling back the tough-on-crime policies that sent incarceration rates skyrocketing in the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, but his executive powers are mostly limited to the federal level — and less than 10% of all prison inmates are locked up in federal facilities.

Presidents do have certain tools to influence local enforcement policy. In the most extreme circumstances, a president can deploy armed forces, as John F. Kennedy did to ensure safe passage for James Meredith, the first black student to attend the University of Mississippi, in 1962. In less extreme circumstances, the president can use the courts, as Obama has done by levying consent decrees against police departments with a history of civil rights violations.

But outside of armed forces and legal action — tools used only in a narrow range of situations — a president’s most effective tool is power over the purse strings.

With so many law enforcement agencies relying on federal funding, a president can try to influence policy by setting certain conditions on the money the Justice Department gives out. The US Supreme Court has described these legal incentives as “relatively mild encouragement.”

One recent initiative, in February 2016, allocated $500 million to law enforcement agencies working to reverse policies that cause “unnecessarily long sentences and unnecessary incarceration.” Overseeing a time of record-low crime rates and the public scrutiny of the post-Ferguson era, Obama “focused on law enforcement interacting more with the community,” Las Vegas police CFO Hoggan said. Facing the terrorism fears after Sept. 11, 2001, George W. Bush emphasized surveillance and militarization. In the wake of record-high murder rates, Bill Clinton pushed forward hiring initiatives that put more cops on the street. Ronald Reagan’s administration incentivized police departments to intensify the War on Drugs by distributing money based on a formula that rewarded agencies for high volumes of arrests and drug seizures.

Outside of armed forces and legal action, a president’s most effective tool is power over the purse strings.

“When local law enforcement agencies look at these performance measurements, they see it as a how-to guide,” said Lauren-Brooke Eisen, a lawyer for the Brennan Center For Justice, a policy institute that aims to reduce incarceration rates. Or as Hoggan put it, “federal grants can swing policy.”

What is the difference between those funding incentives and Trump’s proposal to cut off sanctuary cities?

The Supreme Court may have left legal clues in its 2012 ruling on the Affordable Care Act. One point of debate in that case concerned whether the law violated the 10th Amendment by withholding Medicaid funding from states that did not change certain health care policies.

A seven-justice majority ruled that this was unconstitutional because the “threats to terminate” funding amounted to a “gun to the head.” States, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote, must have a “genuine choice” about whether to accept federal funding.

Though other variables may come into play — most crucially, allegations that sanctuary cities violate federal law — this precedent suggests that Trump’s threat to end funding is unconstitutional.

“Cities would have standing to sue,” ACLU lawyer Jonathan Blazer said. That would leave courts to define the practical applications of Section 1373 and whether following this law is a valid condition for receiving federal money.

Law enforcement agencies have a deep interest in this legal battle. From Los Angeles to Madison, Wisconsin, to New Haven, police chiefs have spoken out about the importance of sanctuary policies. It is the job of federal agencies to apply immigration law, they say, and it is the job of police departments to maintain public safety for all local residents — two necessarily separate duties.

“If people are afraid to talk to us, now our relationship with the community breaks down, and without information, without communication, we cannot get the job done,” said New Haven chief Campbell. “We can only police a community as much as our community allows us to police it.”

If some residents believe that local police are working to deport them or their loved ones or neighbors, “I think you’ll see crime go up,” Campbell said. “It endangers the community and it will endanger the officers. The law is meant to serve humanity, and as long as you are serving humanity, I think the federal government should acknowledge that.” ●