Deonte Hoard had hit that age when a boy on Chicago’s South Side begins to see his friends die. For some boys, that age is 13, or 14, or 15, or maybe a boy is lucky and makes it all the way through high school without seeing any of his friends buried. Deonte’s time came three months after his 16th birthday, in June 2013. It was a warm afternoon and he went to watch his friend Malcolm Whitney play a summer league basketball game. Malcolm was a budding prospect, with a jump shot even better than Deonte’s and a 3.8 grade point average. When Deonte got to the court, he didn’t see Malcolm there, so he called Malcolm’s sister to ask where he was. She told Deonte that Malcolm had died that morning from a bullet to the head.

Fifteen months later, in October 2014, Deonte arrived at school and heard from a classmate that his close friend Cameron Blair had been shot to death the evening before. The two had grown up on the same block, learned to play basketball together, and called each other brothers. Deonte cried in the dean’s office all day until it was time to go home, and when he got home, he cried in the arms of his brothers and sisters and his mother, Ebonie Martin. “He was just so distraught,” she said. “We told him things happen, and things happen to the wrong people, but you’ve got to live on. You’ve got to live on for them.”

Those next five months were hard. He had trouble waking up in the mornings. He didn’t seem to care as much in class. His grades slipped and he became ineligible to play on the varsity basketball team at Urban Prep–Englewood High School. He stopped attending games because he couldn’t bear to watch. This was his senior year and he had hoped to earn a walk-on spot on a college team. But while he couldn’t play basketball for his school, he could still play on the blacktops at Trumbull Park, just down the street from the housing projects on 105th Street where his family lived.

One afternoon in early March, about a week before his 18th birthday, Deonte called his friend Chester Palmer and told him he was just leaving school and asked if he wanted to meet up and hoop in a little bit. Chester, who was 23 at the time, lived next door to Deonte. It was about an hour and a half by bus from Urban Prep’s campus in the Englewood neighborhood to their South Deering neighborhood on the far South Side, and he arrived sometime after 6. He changed out of his school uniform and into some camo pants and a green jacket and then knocked on Chester’s door. We gotta go to the store first, Chester told him. He had to get milk for his baby.

They crossed the courtyard, past the four-story brown-brick buildings of the Trumbull Park Homes and past the empty playground. Railroad tracks lay on both sides of the projects, which sat on the edge of a neighborhood tucked deep into Chicago’s southeast corner, boxed in by three highways, a stretch of marshland, and the Calumet River. Refineries and smokestacks dotted the surroundings. The neighborhood was quiet. It was a place that felt isolated. It was a place where feuds could simmer and boil. “The Wild Hundreds,” some locals called this part of the city. For Deonte and Chester, keeping a close eye on their surroundings was second nature.

The streets were empty except for a black SUV parked in the fire lane down the block. Old, dirty snow coated the ground. Deonte and Chester scurried down the steps and turned onto the sidewalk toward the corner store a block away. The SUV slowly rolled forward in their direction, bumping over the deep potholes that lined the one-way street like a minefield. A dark-colored vehicle, idling in a no-parking zone in the projects, slowly approaching two young black males minding their own business — Deonte and Chester quickly reached the same conclusion. Yo, it’s the police, Deonte said. You dirty?

Chester checked his pockets. He had left his weed at home. Nah, I’m good, he said.

The SUV pulled up beside them. Deonte stopped walking. If the police were going to hassle them, they might as well get it over with. The two eyed the vehicle. “The back driver-side window came down,” Chester said. “They don’t say nothing. A dude’s arm came out the window and he had a gun and he just started shooting.”

They ran. Chester slipped in the snow and fell to the ground. He heard Deonte shout in pain, but Deonte kept running toward the front of their apartment building. Chester hopped up and took off in the opposite direction, around the back of the complex. He felt a sharp pain on the top of his head, from the bullet that grazed him and knocked off his beanie. He rushed into his building and banged on Ebonie’s front door. When she opened it, she saw that Chester’s face was covered in blood.

Deonte lay dead a few yards from his building, his blood soaking into the pavement. His older brother Daquon was kneeling beside him when Ebonie got there. A crowd gathered. Daquon told his mother he had tried to carry his brother home but couldn’t go any farther. He told her he was sorry.

Deonte was gone, but the social forces that led to his death lived on.

Word spread quickly. Soon, Deonte’s principal and several of his teachers and friends arrived. Blue lights flashed against the brick and the sounds of sobbing and wailing and anguish and anger carried across the courtyard. Police officers nudged the crowd away from the body. They asked Ebonie to step back. She said she was the boy’s mother, and at first they did not believe her because she looked so composed. The tears would come later, but for now she had a single-minded focus. Her son was lying there, bloody and lifeless and exposed, and she wanted his body covered. The police did not help her, so she went into her apartment and grabbed a bedsheet. His body remained out there for five hours, as detectives and other official-looking people paced around the scene, jotting notes and taking photos and small-talking.

It was the 53rd of 489 homicides in Chicago in 2015, more than all other cities in America that year and Chicago’s highest total since 2012, a byproduct not of organized gang violence, but of more fractured and chaotic cliques that sprung up in their wake. Another black boy was dead in the streets, and, locals knew, soon another would follow, and then another, with no end in sight, and the only uncertainty was whose name would be on the next memorial T-shirt. Deonte was gone, but the social forces that led to his death, the guns and the beefs and the fear, lived on.

“This is an environment of life and death,” said community leader Jedidiah Brown. “To a lot of young men, it is a fact that a way out is invisible. You’re dealing with people who feel hopeless.”

Ebonie stood there, stunned and confused, as the night turned cold; she had done so much to avoid this ending. She grew up in Englewood and had four children with her high school sweetheart, then moved her family without him 10 miles south to South Deering when Deonte was in grade school. She wanted to escape the violence that had made Englewood notorious. By then, things were better than they had been during her own childhood in the early ’90s, when more than 900 people were murdered each year in Chicago.

By the early 2010s, the city’s murder rate had dropped to its lowest point in nearly half a century, at around 500 a year. But the violence that remained was highly concentrated in the low-income black and brown neighborhoods on the city’s South and West sides. To the residents of those communities, long-term sociological trends were mere abstractions compared to the gunshots they heard at night and the loved ones and neighbors they had lost. To Ebonie and other locals, Englewood still felt dangerous. “Ain’t nothing like Englewood to me,” said Chester’s teenage nephew, who goes by V-Nice and lives in the neighborhood. “It’s worse than all of Chicago.”

South Deering felt safer. The Trumbull Park Homes were under renovation when Ebonie’s family moved in as part of the city’s broad plan to rehabilitate its housing projects, which had been neglected by the government for decades and become havens for drugs and violence. The city had built Trumbull Park in 1938 to serve as one of its whites-only housing projects — a policy that was unwritten but plainly seen. In 1953, the city accidentally integrated the complex when a light-skinned black woman, whom officials thought was white, moved in. When residents found out, they threw rocks and fireworks at the woman’s apartment. Facing pressure from both segregationists and civil rights activists, housing officials split the difference and decided to allow 10 more black families into Trumbull Park. White residents protested, and the city dispatched riot police to prevent further violence. Over the years, whites fled, and by the time Deonte lived there, nearly every resident was black or Latino.

Ebonie thought she had done everything right, then she watched her son get zipped into a body bag and carried away. “That’s when I broke down,” she said. Friends and relatives gathered at her home that night. They were crying and hugging when an upstairs neighbor, a man in his twenties, showed up at the door. He told Ebonie that he knew who had killed her son. They were members of the LAFAs clique, which was based a few blocks away, in the neighborhood’s Jeffery Manor community. He told the family who he thought these men were, and Deonte’s brothers and sisters were familiar with the names. They were Facebook friends with them. Ebonie urged the neighbor to talk to detectives, and the neighbor agreed. But when the detectives arrived, he changed his mind and said he didn’t know anything. “I was pissed,” Ebonie said. “He was too scared to talk.”

Detectives took a statement from Chester at the hospital. After getting treated for the graze wound on his head, he returned home and began packing clothes into a bag. He drove to his mother’s house in Indiana that night. “Just to lay low,” he said. “I just didn’t wanna be around.”

The street game had changed over the years. When Cobe Williams was coming up, gangs dominated the neighborhoods. These were big, organized, criminal enterprises with vast territories, initiation protocols, strict hierarchies, and a business sense — Gangster Disciples, Vice Lords, Black Guerilla Family, Black Disciples, Black P. Stones, and others. Williams began throwing up gang signs when he was 6 or 7 years old. “You were born into it or sworn into it,” he said. “I was born into it.” His father was a high-ranking member of the Black Disciples.

Gang violence was usually tied to business: disputes over territory or money, or campaigns to eliminate drug-dealing competitors. Gang leaders frowned on violence that didn’t help advance the bottom line — violence that would needlessly draw police attention or, worse, spark a war with another gang. “Back in the day you couldn't do this and do that without checking in,” Williams said. “I had to be accountable for what I do and what I say. Otherwise, I risk a violation.” Those who went rogue were punished. Charles Jones, who ran with the Gangster Disciples, said that “all of us listened to what the older guys told us to do and not to do. If they told us to shoot, we did it. If they told us to stop, we stop. It was about business back then.”

Then authorities across the country cracked down on the gangs. Leaders and high-level members were swept into prison. By the end of the 1990s, the old gang social structure had significantly eroded. Yet in Chicago and most every other city, the root problems that had pushed young people into gangs remained. The poverty rate in Englewood increased from 27% in 1970 to 48% in 2015. Around half of all 20- to 24-year-old black men in the city were not working and not in school in 2015, 15% higher than the national rate. Around 75% of homicide victims in the city that year were black, and around half were in their twenties.

Jones, who now spends his days with juvenile offenders for his job with Chicago’s First Defense Legal Aid, and Williams, who now works to prevent violence for the CeaseFire organization, both noticed how their city had transformed over the last 20 years. The old gang structure left a vacuum, and a new social dynamic filled it. In New York City, Baltimore, and St. Louis, locals and police officers called them “crews.”

In Chicago, people called them “cliques.” These were smaller, informal, block-based groups without a strict hierarchy or official initiation protocol or business model. Whereas there had been a few dozen gangs back in the day, there were now hundreds of cliques. They formed and dissolved and changed names. Some had scores of members. Others had several to a dozen. Their territories could be as small as a block or a single building in a housing project. Some cliques had members who sold drugs. Some cliques were simply a union of boys who grew up in the same area and hung out together and gave their squad a cool name.

The old-school gangs had not disappeared. Many young people still repped them. Some cliques claimed affiliation with a gang or originated as a faction within a gang. Some cliques contained members who affiliated with a diverse range of gangs — kids who would have been rivals 25 years ago now running together. Indeed, the relationship between gangs and cliques remained somewhat ambiguous, case-by-case. But Chester Palmer described it this way: “Your gang is what you is. Your clique is who you with.” As the nature of these street groupings changed, so did the nature of the street violence.

Business and drugs, the targeted strikes ordered by shot callers, no longer were the driving forces. “Now that all the structure and leadership ain’t here no more,” Williams said, “everybody doing what the fuck they wanna do basically.” Now, many shootings were caused by personal beefs. Friends took sides with friends, maybe showed their support on Facebook or Instagram, and personal beefs escalated into beefs between cliques.

“Now any conflict can lead to all-out war.”

“Now any conflict can lead to all-out war,” said Jones. “It can be as small as somebody looked at me wrong. Somebody was talking to my girl. It might sound petty, but remember these are kids, and to them it’s not petty.”

The prevalence of guns in Chicago made these disputes deadly. A report from the mayor’s office showed that police confiscated around 7,600 guns in 2012, which was higher per capita than New York City and Los Angeles combined. Though Chicago has strict gun control laws, its central geographic location has allowed weapons to pour in from states with more relaxed policies, like Mississippi, Indiana, and Wisconsin. According to the mayor’s report, 60% of guns used to commit crimes in the city from 2009 to 2013 were purchased outside of Illinois — double the national average of out-of-state guns recovered in crimes.

The mix of guns, anger, disillusionment, and youthful recklessness created a climate of fear and panic, of shoot first or be shot. “You can’t even argue with nobody,” Chester said. “You done laughed at them and now he done shot you seven times, just ’cause you made fun of his shoes. So some dudes think they gotta carry a gun too, just ’cause everybody else is. And so now these two dudes both got a gun, and maybe neither of them wants to pull it, but they scared the other will.”

To Chester, navigating this world required a delicate balance. “You can’t bow down ’cause if you do that they gon’ try to go on you,” he said. “You can’t let anybody talk to you any kind of way.”

It was a delicate balance, but Deonte had mastered it, Chester said. “He ain’t did nothing to put a target on his back.”

The news of his death first popped up on Facebook and then Twitter. It had spread far across social media by the time Ebonie called Urban Prep Dean of Students Aric Brown, who rushed to the scene and passed the news on to other school administrators and a handful of students who were closest with Deonte.

Urban Prep–Englewood was closed the next day, a Tuesday, for ACT testing, and Principal Dennis Lacewell made the announcement to the juniors on campus for the exam. He called state education officials and they agreed to allow the students to take the test on another day. The next day, teachers and administrators lined up at the school’s front entrance to greet the kids in the morning. Most had heard the news by now, and those who hadn’t soon found out and some of them burst into tears on the spot. Many students cried throughout the day, in the hallways, in the bathrooms, in the classrooms. Some went home within the first few hours. Others floated through the day in a daze. Teachers tried to hold back their own tears, but a few could not. “Those days after it happened were the hardest days that I’ve seen here,” Lacewell said. “Some of those kids had to let it out, and they did.”

The school offered counselors. Jimmy Taylor, Cordarryl Williams, and a few of Deonte’s other friends gathered in one of the offices. They cried together, alternating between bouts of sorrow and fury. They talked about how unfair it was, how messed up it was, how this shouldn’t have happened to him and it wasn’t right and maybe they should go find the guys who did it. They felt helpless. “It makes you feel as if whatever you’re doing, whether it’s right or wrong, you have no way out,” Cordarryl said.

Brown, who was in the room with them, calmly listened, then spoke his piece. “I acknowledged that they were hurting and it’s OK to hurt and it’s OK to be angry,” he said. “To tell them that it would be all right would have been a little disrespectful, a little insulting, because at the time I didn’t know if it would be all right for them.” He urged them to keep the peace, asserted that the retaliation wouldn’t be worth it, that making other boys feel the pain they now felt would not ease their own pain. Everybody in the room knew how it could have gone — the back-and-forth killings, the cycles of death and revenge. This had been the nature of the violence they saw around them. And when they left the room, none of them were sure which way this would go. “What Mr. Brown said, it took a while to kick in,” said Cordarryl.

Many students tried to channel their grief into honoring Deonte. They traded memories about him whenever they could. They recalled his goofy smile, ever-present and wide even though he was missing his top row of teeth. He’d messed up his mouth when he was younger, falling on the pavement during a basketball game, and the bridge the dentist made him didn’t fit, so he never wore it. They joked about how much Deonte loved to eat oranges, and how he would try to force Jimmy to eat oranges even though Jimmy didn’t like oranges. “But I eat oranges now,” Jimmy said.

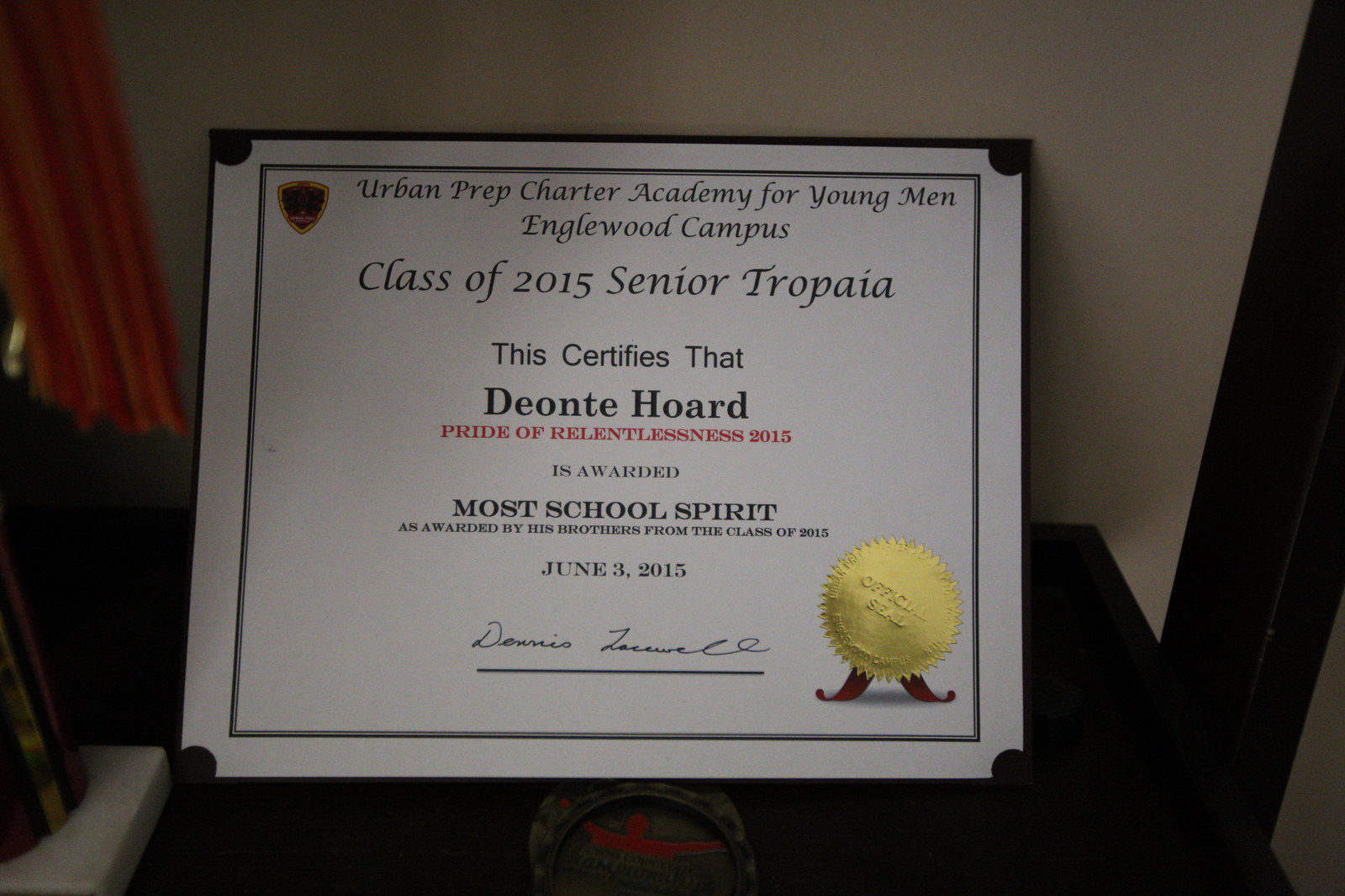

Urban Prep held a ceremony for every college-bound senior. Deonte was killed four days before it.

His friends built a memorial at his locker. On his birthday, they released balloons, ate cupcakes and pizza, and played his favorite songs. They organized photos of him into a slideshow. They held a moment of silence at the daily morning assemblies. They turned the desks he sat in for each class and his usual seat in the cafeteria into de facto memorials, to be left untouched and treated with respect.

One day, a student sat at Deonte’s cafeteria seat. Others asked him to move. Some shouted at him to move. Jimmy walked up and moved the boy himself. He threw him to the ground and they fought. In those weeks after Deonte’s death, there were many fights in his name. “Students were very, very angry and on edge,” said Quan Wilson, who was a dean at the school and a mentor to Deonte. “They felt that if you’re not mourning and feeling what I’m feeling, then you’re the enemy.”

It was the first time a student at Urban Prep had been murdered. The administrators had considered the possibility, had even emotionally braced themselves for it. “You look at the data and you’re grateful every day when this type of violence doesn’t touch one of your students,” said Tim King, the school’s founder. “You just kinda dread that moment when you know it’s gonna happen. That doesn't make it any easier when it actually does happen.”

King had founded the all-boys charter academy in 2006, opening campuses in three of Chicago’s most “high-need communities,” as he put it. More than 85% of students qualified for free or reduced lunch, and over its 10 years, every graduating senior at Urban Prep enrolled in a college, King said. Ebonie had heard about the school. Students wore suits and ties and were required to send out at least 11 college applications. Teachers didn’t use students’ first names but instead called them by “mister.” The Englewood campus was a big, wide, brick building with windows tinted and only on the second and third floors. Those driving past during school hours wouldn't be able to spot a single student. Far in the distance, the Sears Tower peeked up above the trees. But the surrounding neighborhood was filled with empty lots, boarded-up houses, apartment buildings with unpainted wooden staircases on the back, and narrow clapboard homes with iron gates on the doors. The campus was a fortress that seemed to block out the outside world. The school received much local acclaim but had room for only around 1,200 students across the three campuses. A prospective student must be lucky enough to be drawn from a lottery. Deonte Hoard was one of the lucky ones.

He was the youngest among his siblings yet always seemed mature for his age. His loved ones called him “Tookie,” after Crips gang leader Tookie Williams, because when he was a baby he often wore tough, adult-looking facial expressions, and the nickname stuck, even if that's where the similarities ended. At 2, he was reciting rap lyrics he heard on the radio. At 5, he was showing off his dribble moves with a basketball bigger than his head. At 7, he was dancing at social gatherings. At 9, he was dropping moral platitudes on older relatives. “Sometimes when he talks you have to turn around and look at him and say, 'Is this kid really this young?'” said his great aunt Diane. “You just knew he was gonna be something. You just knew.”

He began his freshman year at Hyde Park Academy High School before transferring to Urban Prep for the second semester. He got off to a bad start there. His teachers found him disruptive. Too often, he showed up to class late. He broke the dress code in small, subversive ways, wearing blazers that were too big and keeping his ties loose, sometimes with his collar popped. Administrators heard about a few fights he had been involved in outside of school. He told them he was only trying to break them up, but even then, Brown got the sense that he was “hanging with the wrong people.” To keep away from any bad influences in his neighborhood, Deonte would spend some weekends at Wilson’s or Brown’s place. “He was not a bad kid or this problem student,” said King. “I think he came to us like most of the students come to us — tough backgrounds, tough situations, coming into a new environment. But then he went through the same maturation process that many students go through.”

Within two years, administrators and teachers had seen a dramatic change. By the end of his junior year, he had become a model student in their eyes. He talked about what college he wanted to go to. He joined various clubs on campus and participated in school activities. “He reinvented himself,” Brown said. “It was a great success story.”

He rapped and did flips in the school talent show. During basketball games, he would sit at the scorer’s table, take over the public address announcer microphone, and make jokes for the crowd during time-outs and halftime. He walked some of his classmates home, “to make sure his brothers were always safe,” said Cordarryl. As a senior, he introduced himself to freshmen and greeted them every morning. “I watched a young boy grow into a man and really accept the challenge of wanting to be something in life,” Wilson said

He received acceptance letters from 12 colleges. Each year Urban Prep held a ceremony awarding red-and-gold-striped ties to every college-bound senior. Deonte was killed four days before the 2015 ceremony. Administrators framed a tie and presented it to his mother. They left a seat open for him at graduation and placed his cap and gown on it. Students gave Ebonie a standing ovation. Many of them would be off to faraway colleges soon. Many of them would be escaping the South Side. But they would be leaving with scars. The South Side had taken much from them.

Deonte was the third friend Jimmy Taylor lost during high school. “We don’t really shed tears like that anymore, but you can feel the sorrow in our pain," he said. "I’m not gonna say that it’s, like, normal to me. But it kinda is.”

The LAFAs clique was beefing with the 10-7 clique when Chester moved into the Trumbull Park Homes in September 2013. He learned about the conflict after he saw a memorial for a slain teen in the courtyard and asked a neighbor what had happened. He didn’t know how it started, but he knew that once the bodies started dropping, it didn’t matter how it started. Two more young men with ties to the cliques were killed over the next year or so, he said. One of them used to date Deonte’s sister, Monee.

Deonte’s family had lived in the projects for several years by the time Chester arrived. Chester met Deonte on the park’s basketball courts, and soon they were playing pickup games together on the regular, and soon after that Deonte was spending time at Chester’s house watching TV and playing video games and rocking his baby. As the neighborhood veteran, Deonte schooled Chester on the landscape. The LAFAs were based just to the north of their building, between 99th and 103rd streets, and they often congregated at the gas station on 103rd and Torrence Avenue. The 10-7’s territory was just to the south of their building, on 107th Street. Caught in the middle, Deonte and his family stayed neutral. “We didn’t have beef with either side,” Monee said.

But that didn’t mean they could avoid trouble. When they first moved in, the LAFAs picked on Deonte’s older brother Kingsley. He was new to the neighborhood and a confrontational dude who had a bad habit of mean-mugging, Monee said, and they beat him up a few times. “The LAFAs would jump people for no reason,” Monee said. But Deonte never had any problems with them. Once, when he stepped in to stop a group of LAFAs from fighting a friend, his mother, having gotten word that her son was in a brawl, ran outside screaming. “When I got there, one of the boys said, ‘We didn’t touch your son! He ain’t got nothing to do with it,’” Ebonie said.

Chester quickly learned about his new friend’s reputation. He recalled one day, shortly after they met, when they were walking to the park together and they crossed paths with a group of LAFAs. Instinctively, Chester put his guard up. His face was hard and he kept his eyes straight ahead — the familiar look of a young man trying to both look tough and avoid confrontation. He knew how this worked. A group of locals spotted an outsider and asked that loaded question: Where you from? “If you walking through the wrong part of the neighborhood, if a group of people seen you, somebody gon’ ask,” Chester said. But the boys didn’t ask where he was from. “They shook Tookie’s hand, and Tookie vouched for me, and they said wassup to me,” Chester said. “Everybody loved Tookie. He was cool with everybody.”

Ebonie had 1,000 programs printed and they were gone before all the mourners filed in.

And so everybody was there at St. Andrew’s Temple on 67th Street for Deonte’s funeral. More than 1,000 people showed up, including Mayor Rahm Emanuel, who was in the midst of a tough re-election campaign and faced criticism for failing to reduce gun violence in the city. Ebonie knew the approximate number of attendees because she’d had 1,000 programs printed and they were gone before all the mourners filed in. She was too worn down by grief to take care of the arrangements, so her loved ones — her fiancé, her parents, and her aunties and uncles — had carried the load. Dozens of bouquets framed the casket.

Inside it, Deonte wore a gray suit over a pink shirt. Ebonie did her best to look strong that day, as she accepted the stream of hugs and well-wishes and I’m-so-sorrys from familiar and unfamiliar faces. Several girls who knew Deonte were sobbing and shrieking before they approached her, and when they saw that she was not crying, they asked her, "Ma, how do you make it?" The boys who knew him also cried, but their sobs were angry and their fists were balled. There was talk of revenge.

“Just witnessing somebody you love so much just out on the cold ground where your whole family and all your friends can see it — that would make you want to retaliate,” Monee said. The rumors had been spreading in the hours and days after the murder. By the time of the funeral, many of Deonte’s friends believed they knew who had killed him.

The mothers and fathers met in the basement of St. Sabina church, just off 78th Street. Around 20 usually attended each week. They shared their stories and feelings. The support group helped Ebonie work through her pain. These mothers and fathers had experienced what she was now experiencing, and while they did not have words to ease her pain, they listened and understood, and she found that she needed that.

She had begun to go through Deonte’s things a few weeks after his death. She found a notebook filled with rap lyrics he’d written. “I wanna thank God that I’m here and take advantage while I’m here, and pray my mother don’t have to shed any tears,” read one verse. “But mom just know I promise I’ma give you the big house you always wanted.” She watched the many videos he had posted on Facebook — of him swishing three-pointers in the gym, of him dancing in front of his drama class, of him holding his phone up to his face and spitting a freestyle. He’d posted a video just a few months before his death. “Growing up in the Chi, you already know it’s hard,” he said into the camera. “Thank God I made it. Man, I swear it’s real to stay alive in this battlefield.” She showed off the video, and “everybody was saying he wrote his own eulogy,” she said.

As she listened to the stories in the church basement, she realized that not all murders were treated the same. The local news articles about Deonte’s death mentioned that he’d been accepted into colleges and featured quotes from school officials talking about how he was a good kid who had a bright future. Other mothers and fathers lamented the way the news articles had called their own sons “known gang members” and featured quotes from police officials talking about how the killing was “gang related.”

“They think that just because guys like to hang around outside that they’re bums or menaces,” said Miyoshia Bailey, whose 23-year-old son Cortez was killed in 2013.

“Growing up in the Chi, you already know it’s hard,” he rapped. “Thank God I made it. Man, I swear it’s real to stay alive in this battlefield.”

Bailey remembered the afternoon Cortez died as a warm, bright day. She remembered the phone call she got from her daughter. She remembered going into her backyard and screaming into the sky and then collapsing to the ground and sobbing. And she remembered vividly the feeling that this pain was only her own, that the world was indifferent to it. “Life goes on,” she said. “Nothing stopped. When my son got killed, I look out the window, people still going to work, people still going to school.”

The mothers and fathers had learned the startling truth that most people have no idea how to act around a parent who has lost a child. Most people spouted optimistic platitudes. He’s in a better place. It’s all part of God’s plan. God has gained an angel in heaven. God picked a beautiful flower for his garden. Everything happens for a reason. And so on. Bailey believed that these phrases served only to ease the burden of sympathy and sadness and guilt weighing on the person speaking them. Whenever somebody used the words “passed away” to talk about Bailey’s son, she cut them off and corrected them: “My son was killed.”

“You will not tell me he’s in a better place,” Bailey said. “The clichés, that’s not real.”

Ebonie shared with the mothers and fathers the rumors she had heard about why her son had been killed. In the days after the murder, Monee and her brothers received Facebook messages from friends who affiliated with the LAFAs. “I’m sorry for what they did,” one wrote. Another said, “That shit was bogus.” They told Monee that Deonte was not the target. “They shot the wrong person,” one friend told her. “Your brother was in the wrong place at the wrong time.” Monee knew three of the people she had heard were inside the black SUV. She could pull up the Facebook app on her phone, scroll through her inbox, and find the messages they’d exchanged over the years. “I’m 100% confident about who did it,” she said.

One day, a few months after Deonte was killed, Monee pulled up to the gas station on 103rd and Torrence. A group of LAFAs was kicking it there and among them were those three young men. It was the first time she’d come across them since her brother’s death. “They looked like they’d seen a ghost,” she said. Though they knew her, they said nothing as she walked past them into the convenience store. “No word needed to be said, but their face expressions and how they acted showed me they had some kind of guilt for the situation,” she said.

Though nobody had told her this explicitly, Monee believed that Chester Palmer was the target. Jimmy Taylor believed this too. Monee had heard that Chester had gotten into a minor dispute with a member of the clique. Neighbors came to Monee and her brothers with stories they had heard about how Chester “had started some trouble with some gangbangers.” She wondered why Chester left town so quickly after the shooting. She knew that Chester had been shot at before. This speculation spread through the neighborhood until it had become the conventional narrative. Soon, Deonte’s family blamed Chester for Deonte’s death almost as much as they blamed the young men inside the black SUV. “My brother was at the wrong place at the wrong time with the wrong person,” Monee said.

But while many people around the neighborhood were talking, nobody was talking to the police. Many kept silent out of fear, knowing there was little the police could do to protect them from retaliation for snitching. “People just be really scared of what they think might happen if they speak up,” Ebonie said. “They just wanna make sure their family is protected regardless of what information they have.” A few neighbors told Ebonie that they would talk to the police if she paid them money. The window for sympathy and mourning passed. People began to act like it never happened, Ebonie said. She felt a pressure to move on and get over it.

“I just couldn’t deal with being there,” she said. “I just couldn’t be around it. These people that you’re seeing every day, you know they know what happened. Or they were involved in what happened. But nobody would say nothing. So how can you live? When everybody around you knows what happened but won’t say anything.”

She moved her family to another neighborhood six miles north.

Chester moved back into the Trumbull Park Homes after about two months. He was disheartened to learn that his friend’s family had turned against him. He believed the shooters must have confused him or Deonte for somebody else — maybe they were going after a 10-7s member. “I just almost lost my life and people tryna blame it on me like it’s my fault Tookie got killed,” he said.

He had been shot at before, but that incident was also a case of mistaken identity, he said. He’d fled town because Deonte’s murder left him shook. Back in the neighborhood, he was still shook. He rarely left the house now, and from inside his first-floor living room, he peeked around the drawn curtains every few minutes to see who was in the courtyard. “After dark, I don’t even go outside no more,” he said. “You’re not supposed to live like that. We moved down here and there was a war going on. We moved right down here in the midst of a war, feel me?”

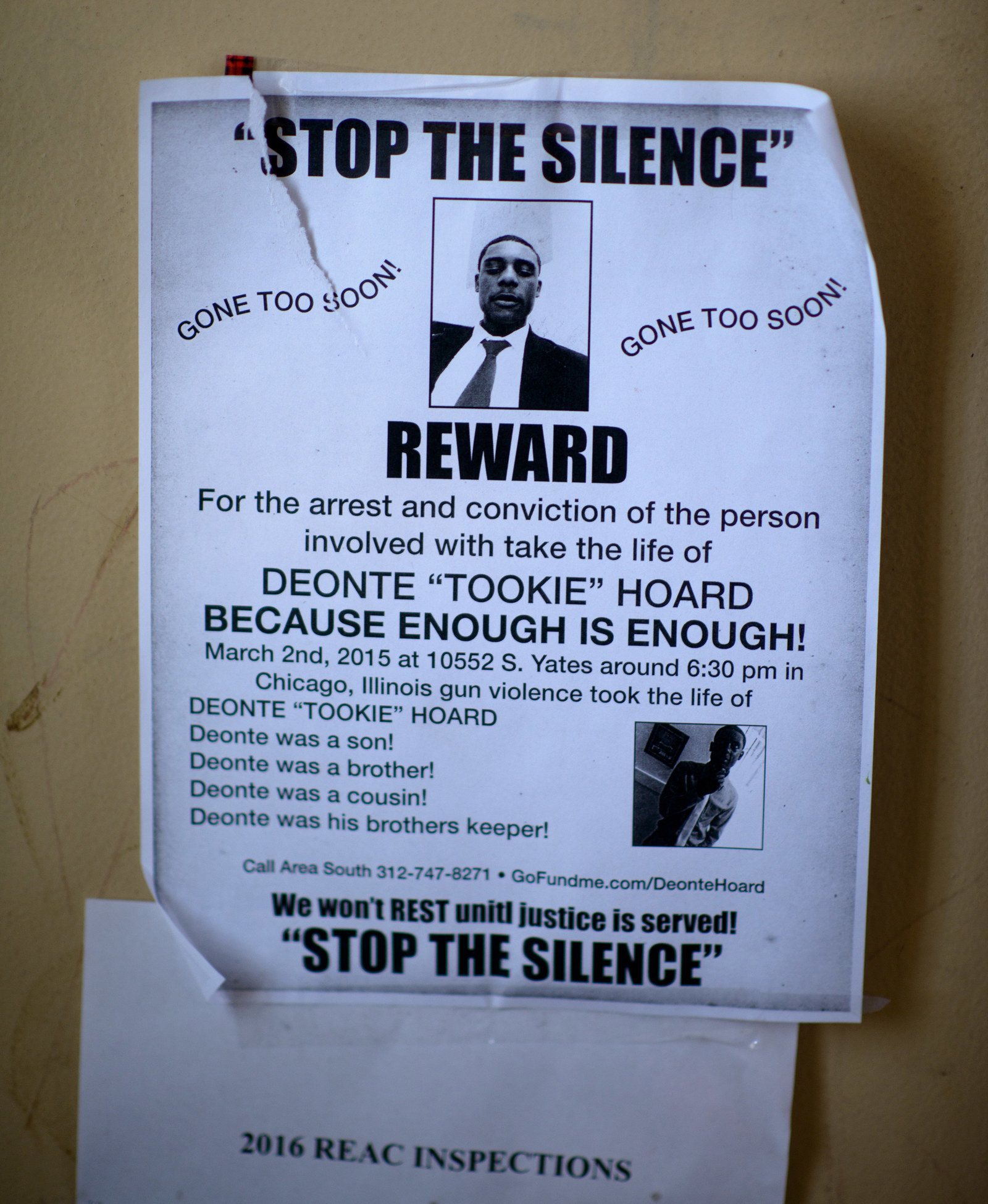

On the one-year anniversary of Deonte’s death, the murder case remained unsolved. Ebonie spoke with the detectives at least once a month. She told them what she had heard about who might have been in that black SUV, but the detectives explained that there was little they could do without physical evidence or a witness who had firsthand information. (The Chicago Police Department did not respond to interview requests for this story.) Ebonie spent the anniversary canvassing the area around the Trumbull Park Homes, passing out fliers that said “STOP THE SILENCE” above a photo of Deonte. Ebonie knew that most gunmen in Chicago don’t get caught. In 2015, the police department solved 26% of homicide cases and prosecutors filed charges in just 6% of nonfatal shootings.

Ebonie thought she had done everything right.

There were twice as many murders through the first three months of 2016 as there were over that stretch in 2015. Many locals feared a bloody summer. In April, Mayor Emanuel selected 27-year Chicago police veteran Eddie Johnson as new police superintendent. Johnson vowed to crack down on any police misconduct he discovered. To bring the murder rate down, though, he said he needed the community’s help. He said, controversially, "I have to emphasize that because these gun offenders are becoming so young, I'm going to ask the parents in the black communities to step up and be parents. You have to be mothers, you have to be fathers. You have to know what your children are doing because if you don't raise them, the streets will."

Ebonie thought she had done everything right. She often thought about the last time she saw Deonte alive. He came home from school and told her he was going to play ball at the park. Urban Prep–Englewood had a playoff basketball game that night, but Deonte didn’t want to go. Since losing his eligibility, he had worked hard to get his grades up to get back onto the team, and his grades had gone up, but his score in math was still a few points too low. He was so close to being able to play, frustratingly close, and he wanted to get his mind off of it. Ebonie told him to return home from the park early. They had to talk about college. Southern Illinois University, University of Iowa, Jackson State, Tennessee State, Kentucky State, Alabama State, Alabama A&M, Florida A&M, Texas A&M, Texas Southern, Paul Quinn College, Grambling. When he returned home that night, they agreed, he would pick where he would go. •