The police arrived at Terrence Dandridge's house at 6 a.m. on May 20. They took him to the police station and booked him on suspicion of armed robbery. That afternoon, he was in an orange jumpsuit with shackles around his ankles, standing before a magistrate judge, who set his bail at $5,000. His public defender told him he'd need to pay a bondsman $1,400 to make bail.

He didn't have that.

Dandridge had been working at a restaurant called Luke for three years. He'd started as a dishwasher, making minimum wage, then got promoted to prep cook, where he made slightly more than minimum wage. He was on track to become a line cook real soon. He took a second job at another restaurant, Johnny Sanchez, owned by the same man who owned Luke. He needed the money to keep paying for the community college classes he'd been taking in business management and culinary arts. He hoped to become a chef. And though he'd been saving for months, he had less than half of what he needed to get out of jail. Until he could come up with that money, he'd sit behind bars for up to two months.

In Louisiana, the district attorney's offices have 60 days to decide whether or not to charge a person for the felony they were arrested for, 45 days for misdemeanors, and 120 days for serious crimes like murder and aggravated rape. If prosecutors have still not filed charges when the time runs out, the defendant must be freed from jail without bail. Most states give prosecutors 72 hours to file charges before a defendant must be released. California allows for 48 hours. New York allows for six days. Florida allows for 33 days. Texas allows 60 days for felonies and 30 days for misdemeanors. Despite the many sweeping changes to New Orleans' criminal justice system made in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, these lengthy pre-charge detentions have survived.

"I don't know of any that are longer than Louisiana," said Steve Singer, a law professor at Loyola University.

The median felony arrest charging decision time during the first half of 2014 was 52 days, according to data collected by the city's Metropolitan Crime Commission, three days more than the same period in 2013.

"A lot of times the DA's office uses all the time they have," said Derwyn Bunton, Orleans Parish's chief public defender since 2009.

"There's too much at stake for the prosecution to have that much time to accept or reject a case," said Norris Henderson, director of the nonprofit Voice of the Ex-Offender. "If the guy had housing, he'd have lost it because he couldn't pay his rent. If he had a job he'd have lost that because he hasn't been present. It's a system set up on the backs of folks who can't pay."

The purpose of the law is to give prosecutors time to investigate the merits of a case before deciding whether or not to formally file charges. The consequence, however, is that poor defendants who can't afford to pay bail end up behind bars even when there is little evidence against them. The practice, known as "DA time," is one of many factors that helped drive Louisiana's incarceration rate higher than any other state's and New Orleans' higher than any other city in the country.

"When I first started working here, I remember calling my friends in public defense offices in other states and telling them, 'You won't believe this,'" said Katherine Mattes, a law professor at Tulane University. "This was a shocker."

Dandridge spent that night in Orleans Parish Prison, which is a jail and not a prison. The facility has been under court supervision stemming from a 2009 federal investigation that found that conditions at the jail were so deplorable they violated inmates' constitutional rights.

Over the next several days, he called relatives but wasn't able to scrape together enough cash. Dandridge was one of hundreds of thousands of people locked up in American jails without having been convicted of any crime, waiting for their cases to move forward to trial or a plea deal or a dismissal of charges. Dandridge, though, had not even been charged.

Dandridge was in jail because he had been around the area of the crime when it took place and because he fit a description that the victim gave to police: a black man with dreadlocks. Enough probable cause for an arrest, and in New Orleans probable cause is enough to hold a felony defendant for up to two months. Dandridge had not stood in a police lineup. The robbery victim had not identified him. No witness had identified him. He had no prior record. His only brush with the law had come six years before, during a traffic stop when a police officer found a small bag of weed inside the car he was riding in. Dandridge was in jail for eight days off of that small bag of weed. Then the driver admitted that the weed was his, and prosecutors dropped the misdemeanor charges against Dandridge. (District Attorney Leon Cannizzaro's office did not respond to multiple interview requests for this story.)

Dandridge's situation is common in New Orleans. But it had been even more common before Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005. In the decade since the storm, thanks to a wave of policy changes aimed at reducing the city's incarceration rate, police have made fewer arrests. From 2009 to 2013, arrests dropped by half, from around 60,000 a year to around 30,000. As a result, the district attorney's office charges a higher rate of arrestees. In 2003 and 2004, the DA's office decided not to file charges against 42% of arrestees. That dropped to 18% in 2013 and 14% in 2014.

City leaders and many advocates cite the lower arrest numbers as one of the signs of progress in New Orleans' criminal justice system over the last decade. The courts began using a pretrial service program to evaluate how high a judge should set bail, and the number of defendants released on their own recognizance has increased by 10%. The city established an independent police monitor. The public defender's office was rebuilt, with a full-time staff of attorneys replacing what had been a part-time network of private defense lawyers.

"Every one of the components of our criminal justice system are all functioning significantly better than they did before Katrina," said Michael Cowan, a Loyola University professor and executive director of Common Good, a network of community organizations formed in the aftermath of the storm. "It would not have been possible to do any of that the day before Katrina."

The reformers had also sought to address DA time. But that was less successful. In the months following the storm, with buildings flooded and lawyers and judges out of the city and county jail inmates shuttled out to prisons across the state, the court system shut down. There was not a single criminal trial for 10 months. The backlog of cases grew, and when the system picked back up again, it moved slowly. Prosecutors said that they needed more than 60 days to investigate many cases. In 2006, around 3,000 defendants were released because prosecutors ran out of time, five times more than in 2004. Newspapers reported that locals had coined the terms "misdemeanor murder" and "60-day murder" to describe the perception that criminals were serving their DA time, then getting released back into the outside world, with no charges likely coming. And the effort to reduce charging decision times never gained momentum.

"We wanted to get rid of DA time," said Bunton. "But that's one area that hasn't changed."

The police had come to Dandridge's house that morning after first speaking with his neighbor, Michael Tolliver. Tolliver was a suspect in an armed robbery in the French Quarter the night before, and when the police showed up to his house that morning, he told them that Dandridge could confirm his alibi. Dandridge just needed to come down to the station, the police told him, and they could straighten this all out.

In a small room at the police station, Dandridge told two detectives that he and Tolliver spent most of the night drinking at a club on Frenchman Street, then headed to a McDonald's several blocks south, then went home. They had nothing to do with any robbery, he told them.

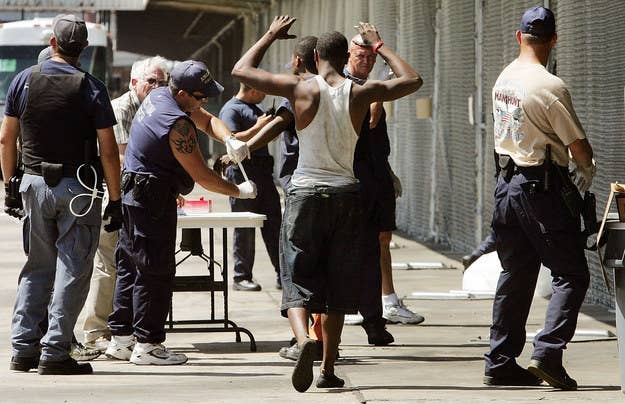

Minutes later, police officers booked Dandridge on suspicion of armed robbery. At Dandridge's first hearing, the prosecutor announced to the magistrate judge that the robbery victim told officers that the suspects fled in a dark SUV. Officers spotted a dark SUV in a McDonald's parking lot a few blocks away from the crime scene. They ran the license plate and the next morning they showed up at its listed address. The victim had also told officers that the suspects were two black men, one with dreads and one with a scar on his face. The man at the address, 27-year-old Michael Tolliver, had a scar on his face. The man Tolliver said he was with the night before, 23-year-old Terrence Dandridge, had dreads. Both were black. These physical similarities, the prosecutor argued, were enough probable cause to justify the arrest.

From jail, Dandridge tried to call his sister, but she didn't pick up. His older sister had been his closest relative for most of his life. His parents were from New Orleans originally, mom from Mid-City, dad from the 7th Ward, but he'd had a falling-out with them when he was a teenager and moved in with his sister in Memphis. Then he headed back down to New Orleans on his own at 16, and bounced around among relatives, eventually ending up with his grandma in the 7th Ward.

On his sixth day behind bars, Dandridge again called his sister, and this time she picked up the phone. She sent the money he needed to make bail. The next day, Dandridge learned that he had been fired from both of his jobs. His boss told him that the restaurants' owner had heard that Dandridge's mugshot was on the news for armed robbery. (A spokesperson for the owner, John Besh, called Dandridge's version "inaccurate" but would not specify further, citing "employment and privacy issues.") And Dandridge had not been cleared yet. With the charges pending, he decided not to enroll for the summer classes he'd been planning to take. He figured the school wouldn't take him.

In June, Cannizzaro's office decided not to charge Dandridge, and he began trying to find a job.

"People don't wanna be around a robber," Dandridge said. "This really kinda like messed up my life."