If you’ve been watching the Brexit series over the last few seasons, you’ll have noticed that the UK and the European Union have been trapped in an emotional death roll of a relationship.

The UK says it wants “out of this crazy love thing!" The EU says, “Fine! Leave!” And then…well…nothing. The UK asks, actually, “Can we stay for a bit longer?” The EU replies mournfully, “Sure, babe.”

AND IT REPEATS. AGAIN AND AGAIN AND AGAIN.

This little mock relationship therapy has been playing out in a tortuous, long-running, correspondence — or, as former Downing Street official Matthew O'Toole called it, the "Dear Donald" letters.

For, um, well, let’s say “historical reasons”, we’ve decided to review the “Dear Donald” canon to see how far our tempestuous relationship has come.

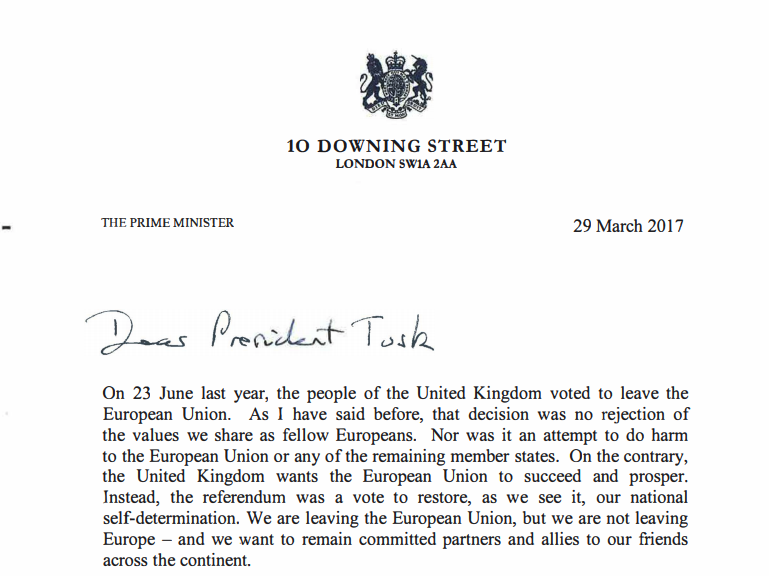

March 29, 2017

Just under a year after the UK had voted to leave the European Union — and 45 years after it first joined — Theresa May wrote to the president of the European Council, Donald Tusk, to announce that she was triggering article 50, the formal process to depart from the EU.

The UK said, “We’re out…and we need just the two years to get our shit together.”

May promised “a deep and special partnership”, a new status the prime minister hoped the UK and the EU would both enjoy.

“To achieve this,” May wrote, with the optimism that typically imbues the dawn of every new relationship, she added that “we believe it is necessary to agree the terms of our future partnership alongside those of our withdrawal from the EU”.

Somewhat boldly, she went on to conclude: “If, however, we leave the European Union without an agreement the default position is that we would have to trade on World Trade Organisation terms.”

Read today, the letter seems from a bygone era, back in the days when the still fresh prime minister was fond of saying “no deal is better than a bad deal”.

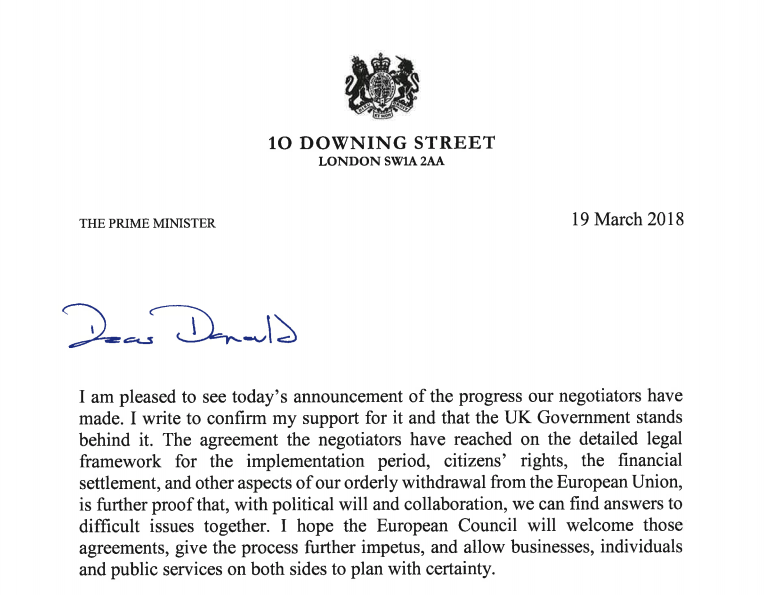

March 19, 2018

Less than a year later, the aspiration of negotiating the terms of the UK’s departure from the EU in parallel with the future relationship — or, as the Brexit bulldog David Davis had envisioned it, “the row of the summer” — was a distant memory.

This time, May wrote to Tusk to let him know how pleased she was that negotiations had progressed on the issues of citizens’ rights, the UK’s financial commitments to the EU, and transitional arrangements.

But just like life more broadly, Brexit sometimes serves you lemons.

The question of how to avoid a hard border in Northern Ireland — a conundrum that literally nobody* saw coming — remained unanswered.

It was in this letter that May, fatefully as it turned out, told Tusk that the UK was committed to “the so-called ‘backstop option’”, an insurance mechanism to keep the border open under all circumstances.

*Actually, quite a few people.

March 20, 2019

“We will leave the European Union on the 29th of March of 2019,” May boomed in Parliament whenever asked whether Brexit would be delayed.

“Will Brexit be delayed, prime minister?” and then came the retort, as reliable as a German washing machine: “We will leave on the 29th of March.” Rinse and repeat, some 50 times.

Nine days before that date, however, with her Brexit agreement twice defeated in Parliament, May sent Tusk another letter.

The prime minister tried to hide her real request in the second to last paragraph of a long exculpation: she asked the EU to extend article 50 to June 30, 2019.

You know how we said two years? We need a few more months.

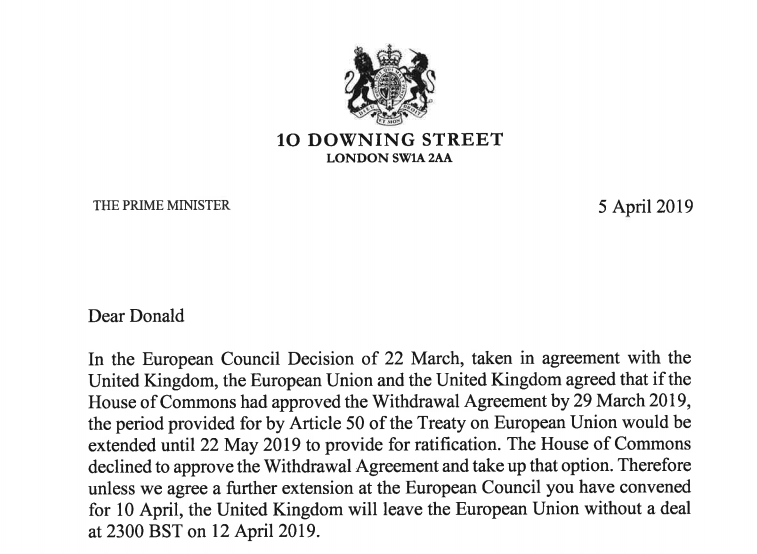

April 5, 2019

The EU said “fine”, you can have a delay but only until mid-April in order to get the Brexit agreement through parliament.

Just a few weeks later, May picked up her pen and wrote again to Tusk, sheepishly admitting that "...having reluctantly sought an extension to the Article 50 period last month, the Government must now do so again."

As in most difficult relationships, with the passage of time, the words between the two parties became fewer, the letters shorter. May once again proposed delaying Brexit until the end of June 2019. Just enough time to get the agreement through Parliament was her thinking.

But EU leaders were sceptical, having long since figured out that the UK was less strong and stable than previously advertised. The response was something like: “Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, ahhh, stop fooling yourselves, you idiots — yeah, sure, you can hang around a bit longer.”

Brexit was delayed to Oct. 31. The UK would have to take part in the European parliamentary elections — and with that, May’s tenure in 10 Downing Street came to an end.

Aug. 19, 2019

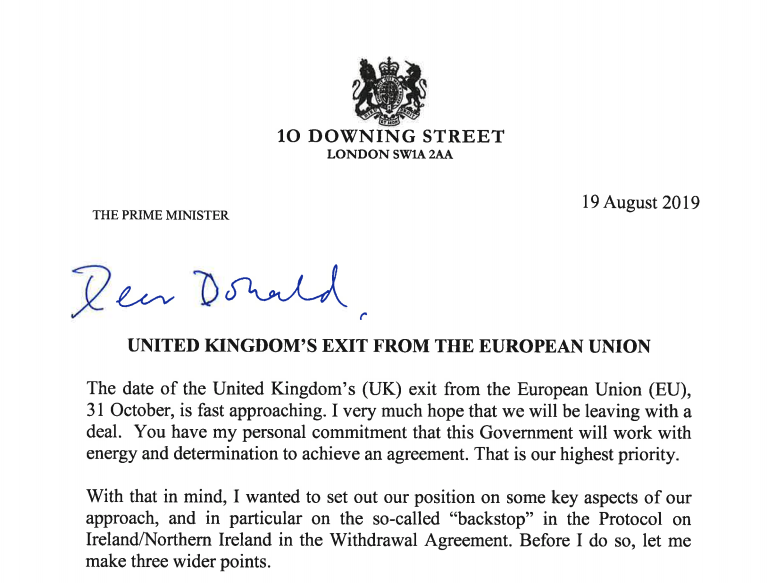

Over the summer, Conservative MPs and members elected Boris Johnson as their leader on a promise of getting Brexit done, come what may, and to leave the EU, with or without a deal, on Oct. 31.

There was a certain, let’s say, swagger and much confidence in Johnson’s first “Dear Donald” letter.

He declared the backstop “undemocratic”, and proposed replacing it with a “commitment” to never erecting a border and finding “alternative arrangements” as well as “flexible and creative” solutions to the issue that confounded so many fine minds.

Johnson pledged to leave the EU at the end of October, “do or die.”

With Downing Street sources briefing that a deal was basically impossible, there was a sudden plot twist.

After a long walk with the Irish Taoiseach Leo Varadkar on the Wirral, Johnson agreed to venture to a place where he and his predecessor had repeatedly and definitively affirmed no British prime minister could dare go: he accepted a regulatory and customs border down the Irish sea.

TL;DR: The dreaded backstop became a permanent frontstop, and a deal was thus sealed.

But, having played Incredible Hulk and difficult to get for much of the summer, Johnson didn't have much time to get his deal through Parliament.

And MPs were unwilling to just wave it through. To avoid the risk of crashing out of the EU without a deal before the necessary legislation was in place, they demanded that the prime minister ask for an extension beyond the Oct. 31 deadline so that they could actually read and scrutinise the agreement before ratifying it.

Oct. 19, 2019

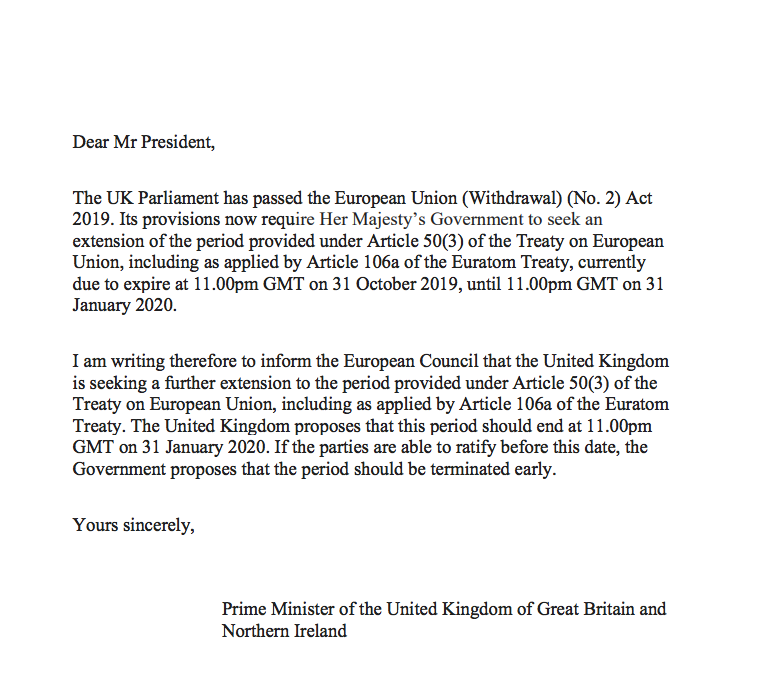

Ten days ago, not for the first time, Johnson penned two points of views.

One “Dear Donald” letter — well, "Dear Mr President" in this case because the tone was deliberately impersonal — that asked to extend article 50 for a third time to the end of January 2020. To really stick it to Parliament and the Europeans, Johnson famously didn't sign this one.

And a second letter that said, more or less, that Johnson was personally unhappy with having to make this request but would have to go along with it.

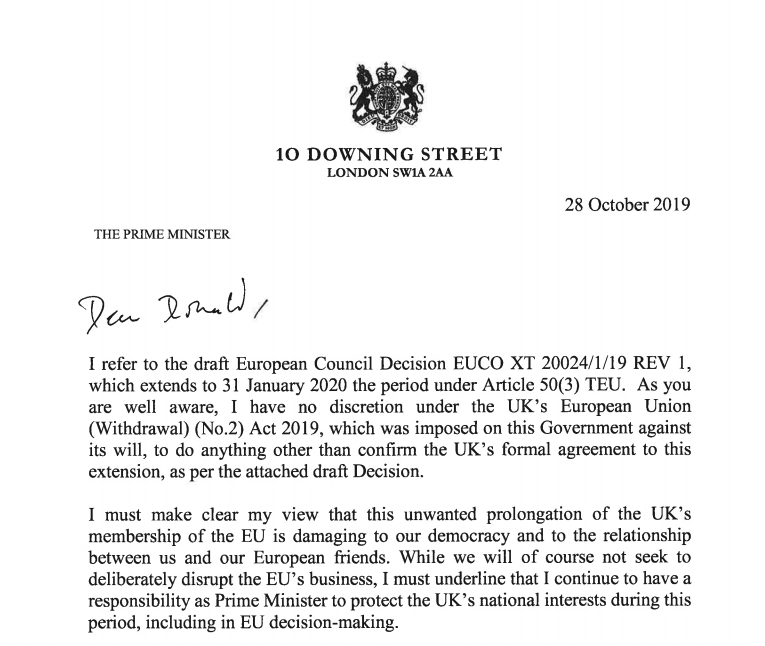

Oct. 28, 2019

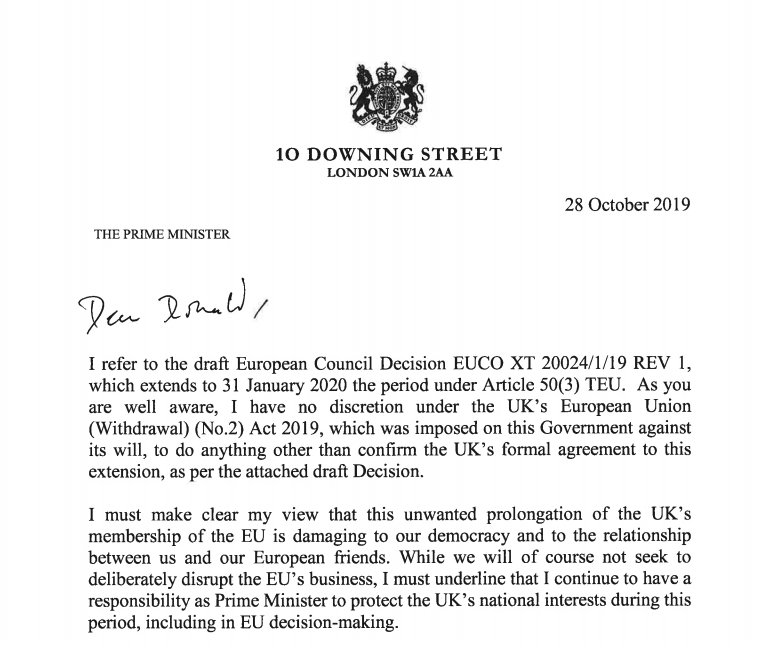

This week, the prime minister who said that he would rather be dead in a ditch than ask for an extension wrote to Tusk for the fourth time in three months to “confirm the UK’s formal agreement” to the EU's offer of an extension to Jan. 31, 2020.

Accepting the "unwanted prolongation" in a short — and signed — missive, Johnson urged “EU member states to make clear that a further extension after 31 January is not possible.”