In hushed tones and under the cover of Guatemala’s darkened sky, then-11-year-old Jessica, her brother, and some of her family members got up in the middle of the night for the long trip to the United States, away from the death threats and into the arms of the parents she hadn’t seen in 10 years.

In the beginning Jessica saw the trek as an adventure, where she got to meet different people and see new places. But the journey soon became tougher than she’d imagined.

“We had to walk day and night, cross rivers, climb hills, and get into buses that were packed with people,” Jessica told BuzzFeed News. “They wouldn’t put on the air conditioner and they would keep telling me that soon we would get to a cooler place.”

The now-15-year-old Jessica, who looks much younger than her age and wears her hair in a long braid that goes to her waist, doesn't look fearsome. But her presence has become the newest specter in the Trump administration's war on immigration, with officials changing policies or proposing measures targeting kids fleeing violence and abuse.

Attorney General Jeff Sessions and President Trump have blamed these kids for gang killings in the US.

“In the three years before I took office, more than 150,000 unaccompanied alien minors arrived at the border and were released all throughout our country into United States’ communities — at a tremendous monetary cost to local taxpayers and also a great cost to life and safety,” Trump said at a speech in Long Island on MS-13. “Nearly 4,000 from this wave were released into Suffolk County — congratulations — including seven who are now indicted for murder.”

The Trump administration is also planning on going after the parents of unaccompanied minors who paid smugglers to bring them to the US as a way to deter more mothers and fathers from doing the same because it puts their kids in danger. At the same time, the administration has killed an Obama-era program that would’ve allowed the most vulnerable Central American kids to apply for asylum in their home countries and get permission to come to the US while their cases played out, circumventing the smuggling dangers officials like Sessions express concern about.

Reuters reported that the Trump administration is also looking into ways to get rid of legal protections that limit how long and under what conditions children can be held in US immigration detention centers. The administration's efforts have prompted the United Nations to consider providing help to unaccompanied minors crossing the US border.

In exchange for passing legislation to protect from deportation young undocumented immigrants who've lived in the country for years, the White House has said it wants to change immigration law to "ensure the swift return" of more newly arrived unaccompanied children and get rid of "loopholes" that allow thousands of children from Central America to seek refuge in the US. The administration claims those loopholes create a magnet for illegal immigration.

It doesn’t make sense to Jessica, whose grandmother, her sole caretaker, started receiving death threats days after gang members killed Jessica's uncle for refusing to pay an extortion fee.

"Sometimes I ask myself why we have a president who wants to send us back even though he knows it's dangerous for kids like us to return to be killed," Jessica said.

Specifically, the administration wants to be able to deny entry to children from Central America, and deport them without having a hearing before an immigration judge through expedited removal — a process that Trump, through one of his executive orders, has asked the Department of Homeland Security to expand. However, expedited removal can't be used against people seeking asylum, as many Central Americans claim at the border.

The White House also wants to stop unaccompanied minors and families from Central America from being released while their immigration cases are pending. Hardline immigration proponents describe the practice as “catch and release,” as if the children were so many fish.

Growing up in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, Jessica knew young girls like her faced rape and death at the hands of gang members. But the dangers only hit home when her uncle was shot by a teenage boy and girl under the direction of the Barrio 18 gang after refusing to pay an extortion fee. The Barrio 18 gang started in 1980s Los Angeles but has since spread and grown into one of the largest gangs in the Western Hemisphere.

Once the same threats were made to the siblings' 71-year-old grandmother, the family — Jessica, her brother, grandmother, and a 9-year-old cousin — felt compelled to take a bus north in the middle of the night, days after the funeral.

They slept in hotel rooms or smugglers' safe houses. On the night they crossed the border into the US, they were stuffed into a hot trailer but had to get out halfway there because there was a police checkpoint up ahead, Jessica said.

The group jumped off, climbed a hill to avoid police, and was once again loaded into the trailer. Jessica said it dropped them off at a river where the coyotes told them to cross and walk down a road to meet another guide.

But when they got there they found two roads. They didn’t know which to take, so they picked one and hoped for the best. As they were walking, their eyes were hit by the headlights of the Border Patrol vehicles. Some people ran, but Jessica and her family stayed put.

“We didn’t run, we were scared,” Jessica said. “I thought they were going to send us back because we didn’t have papers.”

That’s where Jessica was separated from her then-12-year-old brother, Juan, for three days in a detention center. She was with her grandmother and her cousin. She said they felt hopeless not knowing how long they’d be in there. They did their best not to cry.

At the end of three days, she was put in a holding cell with her brother, which many immigrants call hieleras, Spanish for "iceboxes," because they were so cold. The aluminum blankets they received didn’t do much to combat the freezing temperatures, Jessica said.

“But I was just so happy to see my brother because I thought they were going to deport him,” Jessica said.

The pair were put on their first airplane the next day and sent to a center for other unaccompanied minors in New York, where Jessica celebrated her 12th birthday during a field trip to the beach. A month later, she was reunited with her parents, who’d come to the US in 2003 and whom she hadn’t seen in 10 years.

“It’s been good getting to know them,” Jessica said. “Little by little we’re getting closer.”

Ultimately, Jessica and her brother were able to win their asylum case. Soon, they’ll be able to apply for green cards and, later, US citizenship, though their parents are still undocumented. Jessica said she wants to be a doctor or a secretary when she grows up, but is angling toward the medical field because she’ll be able to help more people. Juan has considered joining the Army.

They both go to school with many other Central American kids who came alone or with a family member in recent years. Juan remembers one of his classmates from El Salvador was nervous about his upcoming asylum hearing.

“One day he didn’t show up and later a kid overheard a family member telling the school’s office that he was sent back,” Juan said. “I got sad because he was already here and he didn’t want to go back to his country because MS-13 was there.”

In a memo, Sessions said parents who pay smugglers to bring their children to the US put their children at risk of robbery, kidnapping, and sexual assault, and because of that, immigration authorities should deport or prosecute the parents. Families and immigrant advocates say these are some of the same dangers the kids are running from in their home countries.

For 10 years, their mother, Julieta, delayed bringing her kids to the US, the memory still fresh in her mind of two 7-year-old brothers whom smugglers drugged to keep them awake on the journey north. But eventually the dangers they would face if they stayed in Guatemala outweighed the risks of being smuggled into the US.

Julieta, who asked that her full name not be used because of her undocumented status, said she was left with no choice after her brother was killed and her mother, the kids' caretaker, started receiving threats.

"I was so nervous they would make it to the border and then be sent back, because over there, if they're returned, they're killed or forced into a gang," Julieta told BuzzFeed News.

Like hundreds of other parents in her shoes, Julieta gambled that the long and often dangerous route her kids would take would lead to a safer and financially more stable life for them.

The issue of unaccompanied minors came to the fore as their numbers started to increase in 2012, spiking in 2014 and garnering international attention. During the spike, Central Americans apprehended at the southern border outnumbered Mexicans for the first time and was the same in 2016, according to US Customs and Border Protection.

In fiscal year 2014, the US Border Patrol apprehended 68,631 unaccompanied minors and 68,684 families. The number of kids coming alone dropped to 38,500 this fiscal year, according to the White House, but the number of families rose to 71,500 compared to 2014, though still lower than 2016’s 77,857.

The Trump administration says deported kids are a far smaller group than the number of unaccompanied minors allowed to stay — equaling just 4% of the number of children released into the US in 2016.

It’s unclear if Congress will agree to enact new legislation that would make it easier to send back unaccompanied minors from Central America in exchange for keeping the DREAM Act intact. According to federal officials, the US has deported at least 2,707 unaccompanied minors in fiscal year 2017, according to PolitiFact.

"Because of these loopholes, few [unaccompanied alien children] who illegally enter the country are ever returned home," the White House wrote.

The loophole is actually a 2008 law passed by Congress that allowed undocumented minors from Mexico and Canada to be more easily and quickly sent back home, but requires children from nonbordering countries like El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala to be put in formal immigration proceedings. Trump’s wish list would make it easier for immigration authorities to quickly deport all minors at the border.

Doris Meissner, the former commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service and now the director of the US Immigration Policy Program for the Migration Policy Institute, said “loophole” is not the correct word.

"How can you call something a loophole when there's a statute that governs it?" Meissner told BuzzFeed News.

Being able to reunite with family in the US while their immigration cases are pending is a pull factor for these children and families, a Migration Policy Institute report said. But that’s in addition to the push they receive from the violence and poverty they face back home. The solution, Meissner said, is not to deport them quickly but to increase funding for immigration courts so Central American kids can have a speedy and fair hearing.

"This is ultimately an issue about hearings and deciding the cases,” Meissner said. “The situation we have now where cases take years to resolve because of the heavy caseload is the issue we should be addressing, not pointing at the people themselves as someone who is taking advantage of our system."

Despite a drop-off in new immigration court cases for unaccompanied minors this year, the backlog for their cases has continued to rise, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University, which collects statistics from federal records. The backlog peaked at 88,069 at the end of August; about 16,700 of those are cases that began in 2014.

Overall, the immigration court backlog was at an all-time high of about 621,051 as of the end of September.

Mark Krikorian, executive director of the Center for Immigration Studies, which advocates for fewer immigrants, said the reason the White House is trying to make it harder for Central American kids and families to remain in the US is because current law makes the US a magnet for illegal immigration.

"This doesn't deny that the situation is crappy in Central America but that's true for a whole lot of the world,” Krikorian told BuzzFeed News. “But because Central Americans who manage to get smuggled to the border [and] pretend to be unaccompanied minors are treated differently, it has become an inducement for illegal immigration."

He added, "The reason we don't want illegal immigrant kids growing up here is because we have this DREAMer issue today because previous administrations, for both parties, have simply refused to enforce immigration laws."

Michael Hagerty, a pro bono attorney with Kids in Need of Defense (KIND), said it’s cynical for the administration to pit unaccompanied minors against DREAMers.

“The people behind this plan realize the days of demonizing DREAMers are over so they’re trying to get as much as they can while they still have leverage,” Hagerty told BuzzFeed News. “And now they’re trying to exclude a group of people who are no less sympathetic but less publicized, less established here in the United States.”

Brian was 16 years old when he too left Guatemala for the US. Faced with an abusive father and a family that shunned him in his small town, he decided to join his brother in Los Angeles. With $6,500 he borrowed from his brother for a smuggler, Brian made it to the border by clinging to the top of the Mexican freight train known as the Beast, where migrants often are maimed, killed, or robbed by cartels.

Now 20 years old, he’s had to adjust to his new life without much support, only his brother who was often too busy working to look after him. BuzzFeed News previously wrote about Brian’s struggles to win his case because he lacked legal representation, which can be hard to come by for unaccompanied minors.

“I didn’t even know what a stoplight was, I come from such a small town,” Brian told BuzzFeed News. "I felt so alone and unloved when I first got here."

After being released from a detention center in Texas, Brian came to Los Angeles to live with his brother. Without a lawyer at the time, he didn’t know how to have his case moved to California and as a result a judge in Harlingen, Texas, ordered him deported in absentia in December 2014.

Brian works for minimum wage at a company that makes furniture, but the work is less grueling than the textile work he'd done previously. Brian has picked up English and Spanish since coming to the US — he only spoke Quiché, a Mayan language, back home — and proudly says he can switch among the three.

"These last few years I've been able to build my own community," Brian said. "Knowing that people love you is the most important thing — not money. That won’t make you happy."

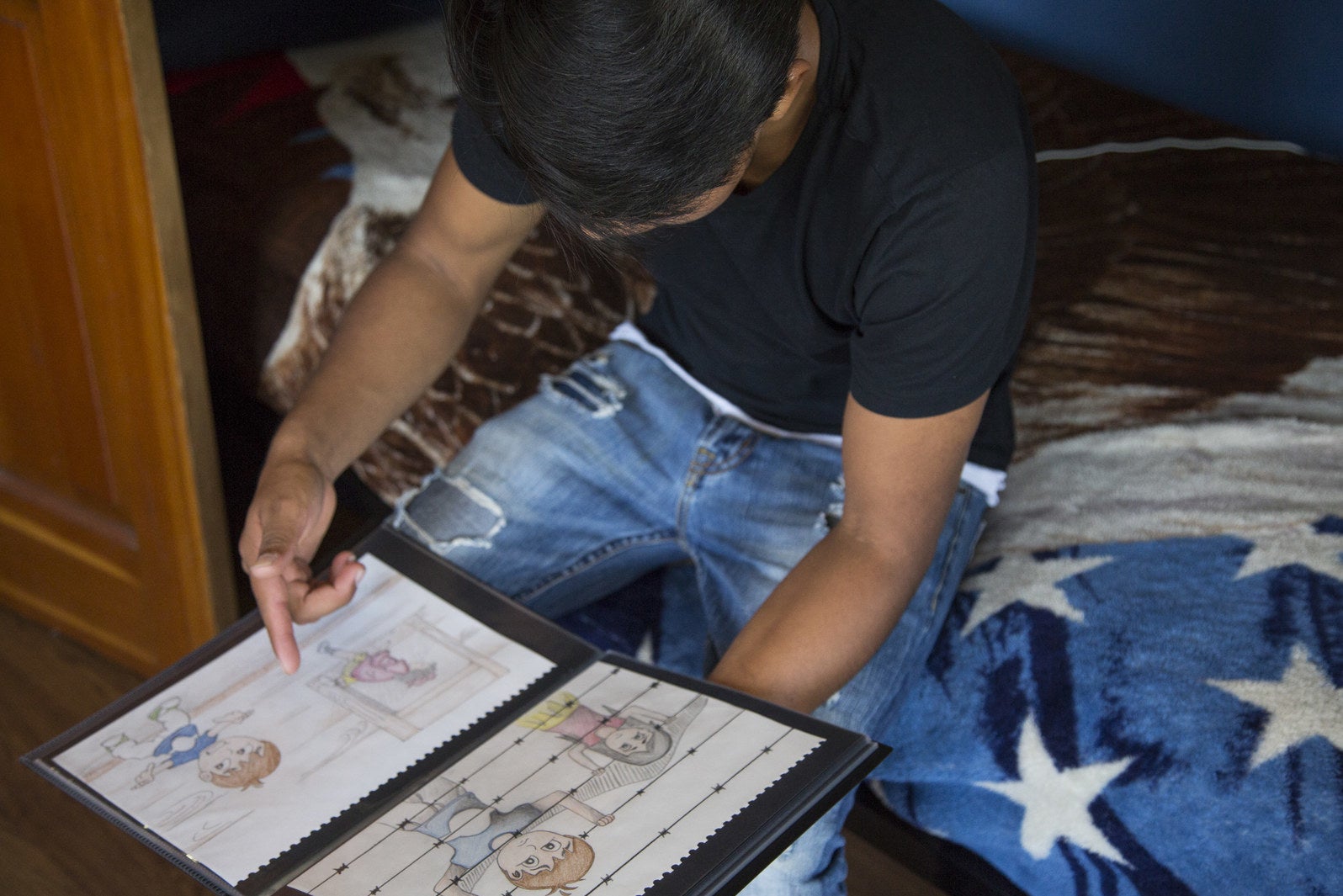

Part of his community is the Esperanza Immigrant Rights Project, an advocacy group that helps unaccompanied minors find attorneys. He volunteers with them and draws images of abuse or violence to help kids who found themselves in similar situations to his explain to lawyers why they fled. When Brian first walked into the Los Angeles offices of the organization, he cried after struggling to find the words to explain that his physically abusive father was the reason he left Guatemala. He said the pictures he draws makes it easier for children start talking about mistreatment or persecution.

The Esperanza Immigrant Rights Project was able to have his case reopened, and he won asylum in June. It was no easy task but at least he had his day in court, Brian said, which the Trump administration is trying to make more difficult.

“It’s hard enough being in this situation, especially if you’re alone, and now they want to pass laws to make it harder for us to win our cases?” Brian said. “You’d be sending them back to their deaths.” ●