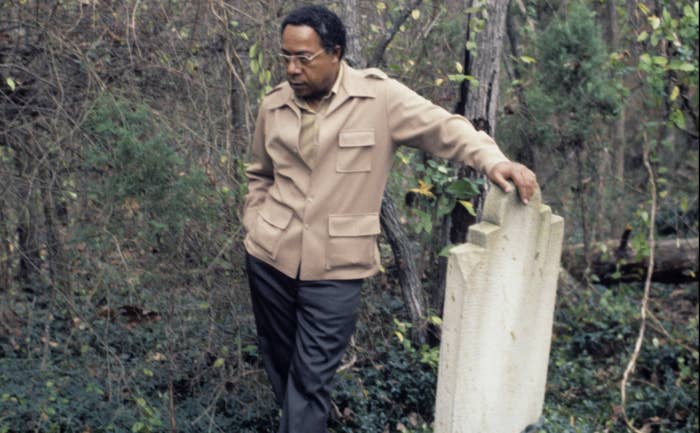

Alex Haley died broke. The celebrated author of The Autobiography of Malcolm X and Roots, two of the most widely read American books of the 20th century, was so deeply in debt that after he died of heart failure in 1992, his family auctioned his Pulitzer to pay his bills.

Haley’s fall was steep. Roots — the book, published in 1976, and the blockbuster ABC miniseries in 1977 — was a groundbreaking work, an epic saga in which Haley claimed to have been the first and only person to have traced his family line from the first African slave brought to America. It was also a best-seller, moving millions of copies, and sparking a nationwide interest in black genealogy and the history of slavery.

But by the time of his death, all Haley had left was his reputation, already damaged by accusations of plagiarism, which would soon buckle under sustained assault. The next year, Village Voice reporter Philip Nobile would publish a detailed attack on Roots. Nobile alleged persuasively that Haley had made up or altered important details, particularly his supposed discovery of an African ancestor named Kunta Kinte who was the first in his family to be enslaved.

The slave known as Toby was likely not the same person as Kunta Kinte, who probably never existed as Haley wrote him. There’s no concrete evidence that Kinte’s daughter Kizzy ever existed, and the biography Haley gave of his great-great-grandfather, the enslaved gamecock trainer Chicken George, contradicted basic historical facts. Nobile proclaimed Roots “the modern era’s most successful literary hoax,” a fraud enabled by Haley’s deception and the refusal of guilty white liberals to take on a cherished cultural symbol. Though Haley’s Pulitzer was not rescinded, it is now generally accepted that Roots is more historical fiction than history.

Haley’s original book, and by extension the miniseries, was marred by poor scholarship and deception in pursuit of an admirable goal, what Haley saw as uncovering the journey of every black American whose history was destroyed by the transatlantic slave trade. The History Channel’s new remake, though a powerful tribute to the original, suffers from a desire to give its audience a sense of justice the enslaved could never have enjoyed. This is the “Django Problem” — that idea that the only acts of resistance that are legitimate and worth remembering are those that involve violence and that resulted in the death of slavers.

The remake, produced by original Roots producer David Wolper’s son, Mark Wolper, and original Kunta Kinte LeVar Burton, is described by The Hollywood Reporter and the New York Times as Roots for “the Black Lives Matter era.” It is both a tribute to, and attempted correction of Haley, with THR gingerly noting that the producers wanted to incorporate “historical material that has come to light in the 40 years since Haley's book first was published.” But in making these corrections, the new series makes a few missteps of its own.

The original 1977 miniseries adaptation was a cultural event that, in all likelihood, cannot be imitated in an era where cable and the internet compete for viewers. An estimated 130 million Americans watched part or all of the eight-night broadcast, and 80 million watched the encore. The population of the United States was only 230 million in 1977, which means more than half of all Americans watched all or part of Roots. White supremacist groups burned crosses at the headquarters of NAACP chapter and the local ABC affiliate in Nashville in response to the broadcast. In Washington, D.C., legislators skipped President Gerald Ford’s State of the Union speech to see a special screening of the first two episodes. Students in high schools and colleges across the country redoubled their demands for more instruction in black history. Ronald Reagan, just a few years away from becoming president, called Roots “destructive” and complained of anti-white bias. It was as if people were watching the Super Bowl, only instead they were watching a 12-hour miniseries about one family’s triumph over the horrors of slavery.

Just as remarkable was that slavery had never been portrayed that way in movies and television. In the 1960s and 1970s, spurred by the civil rights movement, historians were delving deeply into the daily lives of slaves for the first time, but popular portrayals of the institution, like D.W. Griffith's Birth of a Nation and Gone With the Wind, invoked loyal, happy slaves who identified with their white masters. If Roots was a failure as a historical text, it was nonetheless closer to the truth of slavery than much of a hundred years of scholarship that denied both the agency and humanity of the enslaved. "It opened up the eyes of a lot of white viewers particularly, to this part of the black experience, which people had tended to sugarcoat,” Eric Foner, a professor at Columbia University and Pulitzer Prize–winning historian, told BuzzFeed News.

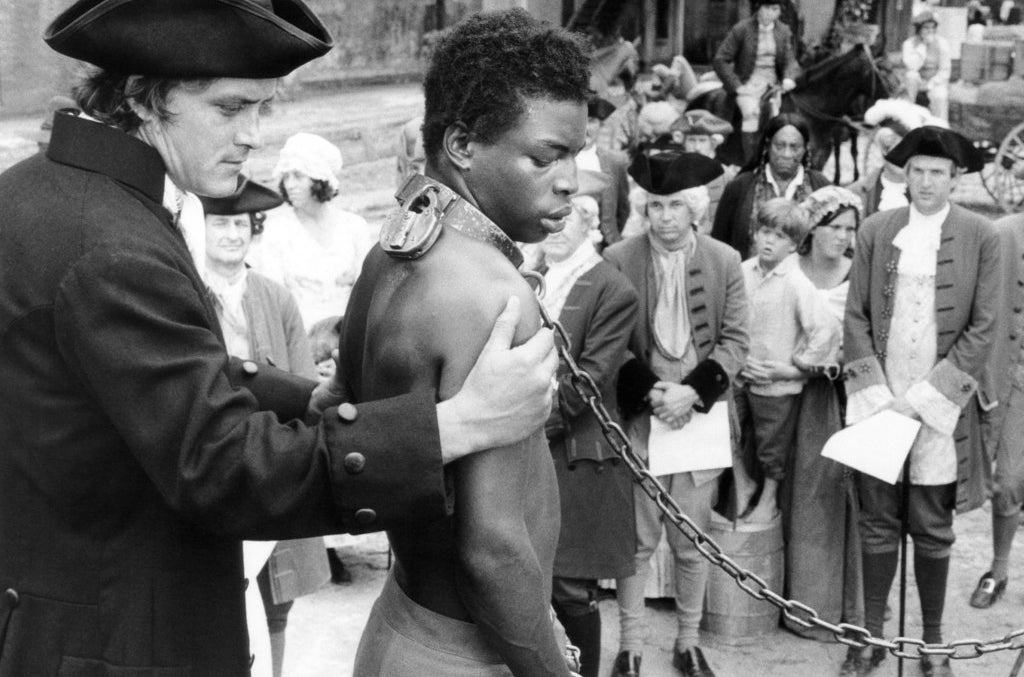

Americans had never seen anything on network television like the excrement-coated hold of a slave ship, or heard the wails of human beings kidnapped and chained, never to see home again. They had never seen anything like the spider web of whip scars across Kunta Kinte’s back, or heard a slave owner glibly mention that he had raped his way across the county, leaving a generation of his own children in bondage. They had never heard the cries of a child being sold away from her parents. They had never seen the acts of resistance and deception, large and small, employed by slaves struggling to balance their dignity with their survival. They had never seen the black American story traced through the middle passage to an origin in West Africa. And on primetime network television, no less.

“We were just starting to, in those years, try to teach courses in black history,” David Blight, an author and professor of history at Yale told BuzzFeed News. “Seeing the capture of Kunta Kinte in Africa, seeing the transport in slave ships, and seeing the brutality in plantation life in the Colonial period, it was sui generis, it was a new thing to see in this medium.”

At their best, stories about slavery remind us of the humanity of both the enslaved and the slavers, the better to recognize the incredible resilience of those who persevered through one of the great crimes of human history and to understand how those who participated in it could have done so. They show how the political and economic effects of the slave trade persist into the present. But the risk is that, in Hollywood’s discovery of the rich and untapped lives of the enslaved, the stories can be warped to meet the political demands of the moment, conforming to our emotional whims rather than historical truth.

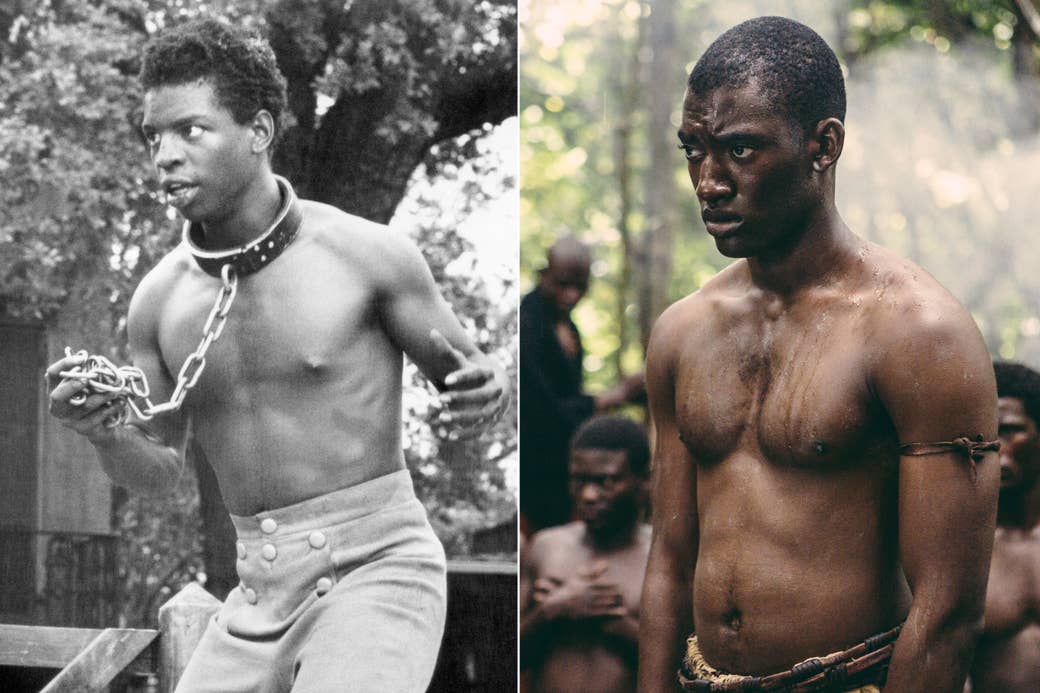

Levar Burton (left) as Kunta Kinte in 1977, and Malachi Kirby (right) as Kunta Kinte in 2016.

“People still have a hard time talking about enslavement, but before Roots, it had been nearly erased, forbidden, too shameful to speak of in the mainstream or relegated to the cartoon stereotypes of Gone With the Wind,” Isabel Wilkerson, a historian and Pulitzer Prize–winning author, told BuzzFeed News in an email. “It may not have aged as well as we might like and there may be questions about aspects of the research, but it was a turning point in America's relationship to its original sin, and it opened the way for most every work that followed that explores the effects of enslavement on America. It broke the silence on the unspeakable.”

Perhaps because the great success of both the book and the 1977 miniseries, doubts about Roots' historicity emerged almost immediately after publication. A journalist in the Sunday Times of London, Mark Ottaway, raised questions about Haley’s portrayal of Juffure and alleged that the griot Haley spoke to was not a griot at all, while historians disputed whether Kunta Kinte and Toby could possibly have been the same person. Those doubts trickled down to the broadcast — some TV reviewers wondered aloud how factual the story was.

Haley danced around the question of whether Roots was fiction or nonfiction; in 1976, he described it as “faction,” a combination of the two. But his publisher pushed for the book to be stocked in the nonfiction section of bookstores, and a great deal of Roots' power came from the notion that Haley had done something no one else had ever done, which is discover the identity of his first African ancestor to be enslaved.

Haley’s portrayal of 1769 Juffure, at the time a city of thousands, as a tiny village untouched by European influence, obscured the reality that Africans were most frequently sold into European slavery by other Africans, through local conflicts fueled by European demand for slaves. As Alex Haley biographer Norrell writes in his book Alex Haley and the Books That Changed a Nation, defending himself to Ottaway, Haley acknowledged that his characterization of Juffure was ahistorical. He told Ottaway that he had tried to create an “Eden” for black people, wanting to “portray our original color in its pristine state[.]” According to Norrell, “The more doubtful his critics were, the more adamant Haley became that Roots was factual.” Later, Haley accused Ottaway of trying to “impugn the dignity of black Americans’ heritage.”

There were other issues with Haley’s history. Kunta Kinte is portrayed as the lone slave conscious of his African identity surrounded by ignorant American-born slaves, even though many slaves at the time would have been foreign-born — the better to fit the Haley family story into the classic bourgeois American narrative of successful immigrant striving against long odds. “When Kunta Kinte shows up in the 1760s in Virginia, nobody else has any sense of Africa on his plantation. That’s ridiculous,” said Foner. “The people who he would have encountered were Africans. The vast majority of the slaves were brought in between 1730 and 1770. These were not people who had lost their African names, heritage, and everything.”

In the remake, more slaves retain fragments of their African identities. Juffure is a thriving city whose residents use guns, ride horses, and occasionally, enslave their rivals — though the show carefully notes that the scale and nature of African slavery was different from the industry that would serve as a cornerstone of labor in the United States. Upon capture, Kunta Kinte asks, “How long must I serve?” If Haley wanted to paint a picture of the Gambia as an “Eden,” the new Roots wants to establish Juffure as part of a modern civilization; the last time Kunta Kinte sees his parents, he argues with them over wanting to attend university in Timbuktu rather than becoming a Mandinka warrior, which is all Haley’s original character aspired to.

The new Roots has rejected the innocence of Haley’s Eden, but it has not resisted the desire to construct a narrative that fits the politics of the moment. Though bolstered by strong performances and modern filmmaking techniques, the new Roots is a classic gritty reboot: The characters are, on balance, more violent, more youthful, and more physically beautiful than their '70s counterparts — including the white slave owners. It strives for an aesthetic of realism rather than being realistic. Too often, it gives the audience what it wants instead of what it should see. THR reported that Mark Wolper had tried to show the original to his son, who said, “[I]t really doesn't speak to me."

British actor Malachi Kirby as Kunta Kinte, though compelling in the role, is a far cry from the devoted innocence of LeVar Burton. This Kunta Kinte racks up a Nat Turner–esque body count of white racists, even after being brought to the New World. In the 1977 Roots, Kunta Kinte is whipped within an inch of his life before he answers to the slave name Toby. The scene is one of Roots’ most memorable for several reasons: It symbolizes the futile but heroic resistance of the enslaved to the violent erasure of their culture and identity, and it tells the audience that there is no justice for a slave in 1769, only survival. That scene is reproduced in the new Roots, only Kunta Kinte manages to extract bloody vengeance from the overseer not long after, with no consequences. This decision not only ruins the pathos of the original scene, but at a time when cops can kill black men in the street on video without ever even facing charges, it rings particularly false.

In the hands of Louis Gossett Jr., Kunta Kinte’s mentor, Fiddler, was a model of subtle subversiveness, bowing to his master but mocking him behind his back. In keeping with the tone of the remake, and perhaps the demands of a modern audience, Forrest Whitaker’s Fiddler dies defending Kunta Kinte — killing two slave patrollers before being stabbed to death. Kunta Kinte’s daughter, Kizzy, manages to kill one of the white men who drags her off after she is sold.

Kunta Kinte’s refusal to become a slave in his own mind is his greatest act of heroism in the original Roots. His bravery is admirable, but it is also ordinary in the best way, in that it convincingly reflects the day-to-day courage of the enslaved. The new Roots says this is not heroic enough — he must also be a ninja. As satisfying as the onscreen deaths of the slavers of might be, it’s a standard that diminishes the incredible courage and resilience of the enslaved, as though the true failure to end slavery was theirs.

Much has been made of Hollywood’s recent fascination with stories about slavery, but the truth is that few films and TV shows have actually been made — the upcoming Birth of A Nation which made history at the Sundance Film Festival, the record-breaking WGN series Underground, and of course, Django Unchained and 12 Years A Slave — and there is much more to be told. But in telling the stories of the enslaved, their heroism must not be reduced to their ability to kill their oppressors.

After Willie Lee Rose’s 1976 piece in the New York Review of Books criticizing Haley’s history, according to Norrell, Haley defended his departures from fact in Roots by saying, “I was just trying to give my people a myth to live by.” Haley’s myth was an unforgivable journalistic sin — that of fabulism — but it was a myth that brought Americans closer to the truth of slavery, and in doing so, obliterated older myths that had heretofore allowed Americans to pretend that the foundation of slavery was anything but violence.

It was the lifting of that veil of ignorance that paved the way for our current revaluation of slavery and the Civil War, and the recognition of the ongoing centrality of both in the American story. But the temptations of myth are ever present, and the peril of the Roots remake and the stories to come is that, unable to bear the pain of the past, we discard the myths of the past only because they are no longer useful, and find new myths to fit the moment.