Andy and Lana Wachowski seem to have had an incredibly blessed Hollywood career. Their feature directorial debut, Bound, was a noir-y thriller about two lesbians which opened in 1996, pre-Ellen, to wide acclaim. The siblings' careers then exploded after their 1999 sci-fi adventure The Matrix broke visual effects boundaries and blew audiences' minds with a heady story that touched on issues of virtual reality and the nature of perception itself. The film grew to be such a cultural juggernaut that Warner Bros. agreed to let the Wachowskis shoot the subsequent two sequels back-to-back, and the first of those films, 2003's The Matrix Reloaded, still counts as one of the most successful R-rated movies ever made.

Rather than cashing in and pursuing comic book movies or Hasbro tie-ins, however, the pair have crafted a rarefied body of work, making narratively challenging, visually daring films with budgets normally reserved for sure-thing franchise blockbusters — even after some of those films proved to be significant box office failures. The filmmakers' great good fortune has extended up to their latest film, Jupiter Ascending, opening Friday, a sci-fi space opera made for a reported $175 million from an original screenplay by the Wachowskis. The only other filmmaker working today who can command that kind of budget for a movie not based on previous material is Christopher Nolan — and he has many more recent successes to his name.

"We have a lot of projects that have not gotten made. Some of them are some of the best writing we've ever done." —Andy Wachowski

One is left wondering how, in an industry that has grown chronically allergic to risk and originality, the Wachowskis have managed to keep confidently striding forward to the beat of their own distinctive (and expensive) drums. But the Wachowskis see the path they've charted through Hollywood as less of an unbroken stride and more of an arduous, continual struggle.

"We constantly run into walls," Andy Wachowski told BuzzFeed News, sitting next to his sister in a Los Angeles hotel suite. "Constantly. We have a lot of projects that have not gotten made. Some of them are some of the best writing we've ever done."

It’s not that they seek out those walls, exactly; it’s just that their sensibilities mean they can’t really avoid them, either. "When you unpack all of [our] experience," Lana added, "you can see that we have this kind of unique take on or an integrity to the piece of art that we're working on."

To better understand how and why they managed to remain steadfast to their artistic convictions, the siblings walked BuzzFeed News through the breadth of their career, and what challenges faced them along the way.

Assassins (1995)

The Wachowskis first arrived in Hollywood as twentysomething comic book writers with grand ambitions to push their storytelling beyond established conventions. In 1995, they landed their first produced screenplay with the thriller Assassins, starring Sylvester Stallone and Antonio Banderas as rival professional hit men, and shepherded by Hollywood heavyweights Dino De Laurentiis (as an executive producer) and Joel Silver (as a producer). Getting the script to the screen, however, proved to be a trial that would shape the rest of their careers.

Andy Wachowski: [Assassins] was the second script that we had written. We wrote this other thing called Carnivore. It got a lot of interest, but it was too weird. It was about eating the rich, and so it wasn't popular for some reason.

The first cash payment that we got on Assassins was from Mel Gibson. He had read it, and he was like, "Where did this come from?" We were like, "Look, we have to make a decision," because we had an offer from DDLC, [producer] Dino De Laurentiis' company. Then our agent told Mel's company that, "You know, look, these guys are super poor. They're calling from a gas station phone right now." So Mel Gibson wrote us a check for, like, $1,000 each to wait 24 hours or something like that. We were like, "$1,000! Yes! We're rich! We're rich!" And then [Mel] was like, "No." The time period ended, and we optioned the script to Dino.

Lana Wachowski: He gave us an option payment, which was $10,000, and we were like, "Oh my god! We don't have to work for years!"

AW: Retirement plan!

The script bounced around Hollywood — at one point, Wesley Snipes was attached to star with Joe Johnston directing — until it ultimately landed at Warner Bros., with Richard Donner (Lethal Weapon, The Goonies) directing.

AW: Right off the bat, we did not click with Mr. Donner. He wanted to make something that wasn't as dark as our script. And eventually he took it away.

LW: There was all this symbolism and subtext, and he wanted more of a straightforward action thriller. We were interested in the notion of pocket moral universes, and the way that … even people in an everyday world can have a separate morality inside their pocket universe. Richard Donner wasn't interested in that idea.

AW: I mean, it's called Assassins, and the very first scene of the film, [Stallone's character] goes out and he kills a guy. And in Donner's version, Stallone doesn't kill him. He has to shoot himself. He like... gives him the gun, and he says, "It's chambered," because Donner couldn't connect to the character if he was as assassin. So they did a page-one rewrite. And you know, we tried to take our names off the project.

LW: They wouldn't let us.

AW: [Producer] Joel [Silver] was like, "This is your first movie, and you're trying to take your name off of it?! That's crazy!" And we were like, "We don't care. We don't like it." But it gave us the perspective of, we'll never survive as writers in this town.

LW: We better become directors.

Bound (1996)

The popular mythology is that Bound was an audition piece for the Wachowskis to secure the job of directing The Matrix — an idea that caused both Andy and Lana to roll their eyes. "Joel made that up," Lana said with a sigh.

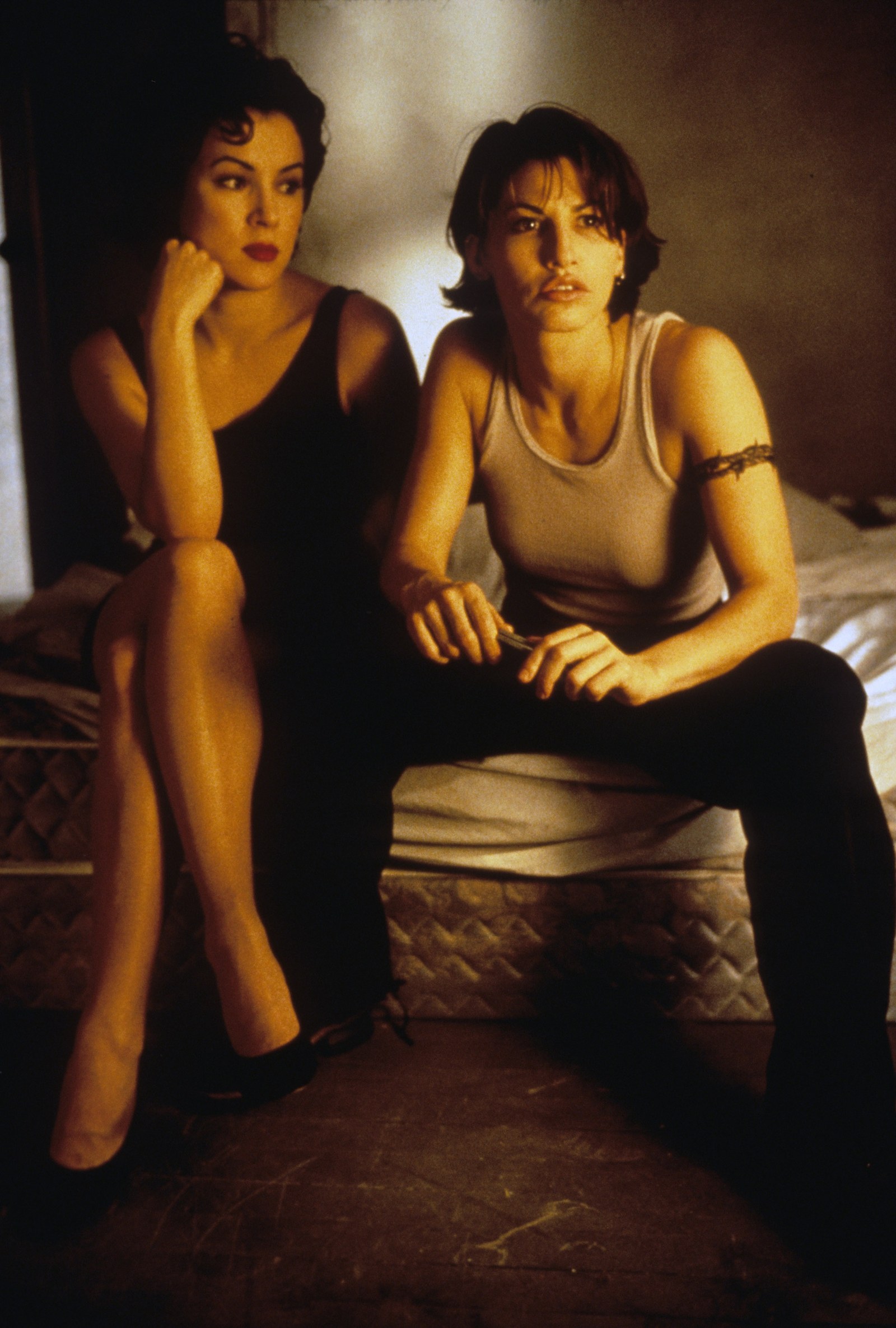

Instead, after metaphorically washing their hands of Assassins, the Wachowskis said they decided simply to focus on making their own directorial debut. The film was a sleek — and relatively inexpensive — neo-noir thriller about Violet, a gangster's moll (Jennifer Tilly) who starts an affair with Corky, a butch ex-con (Gina Gershon). Together, they scheme to steal a fortune from the mob and pin it on Violet's boyfriend Caesar (Joe Pantoliano).

LW: Dino didn't want it to be lesbians. At first, he liked the idea, but then he read the script, and he was like, "Don't make it lesbians. Make it a guy. It'll be more commercial." We were like, "No. We want to do it. The reason to make it for us is because of the dynamic of the characters and what it says about our present culture."

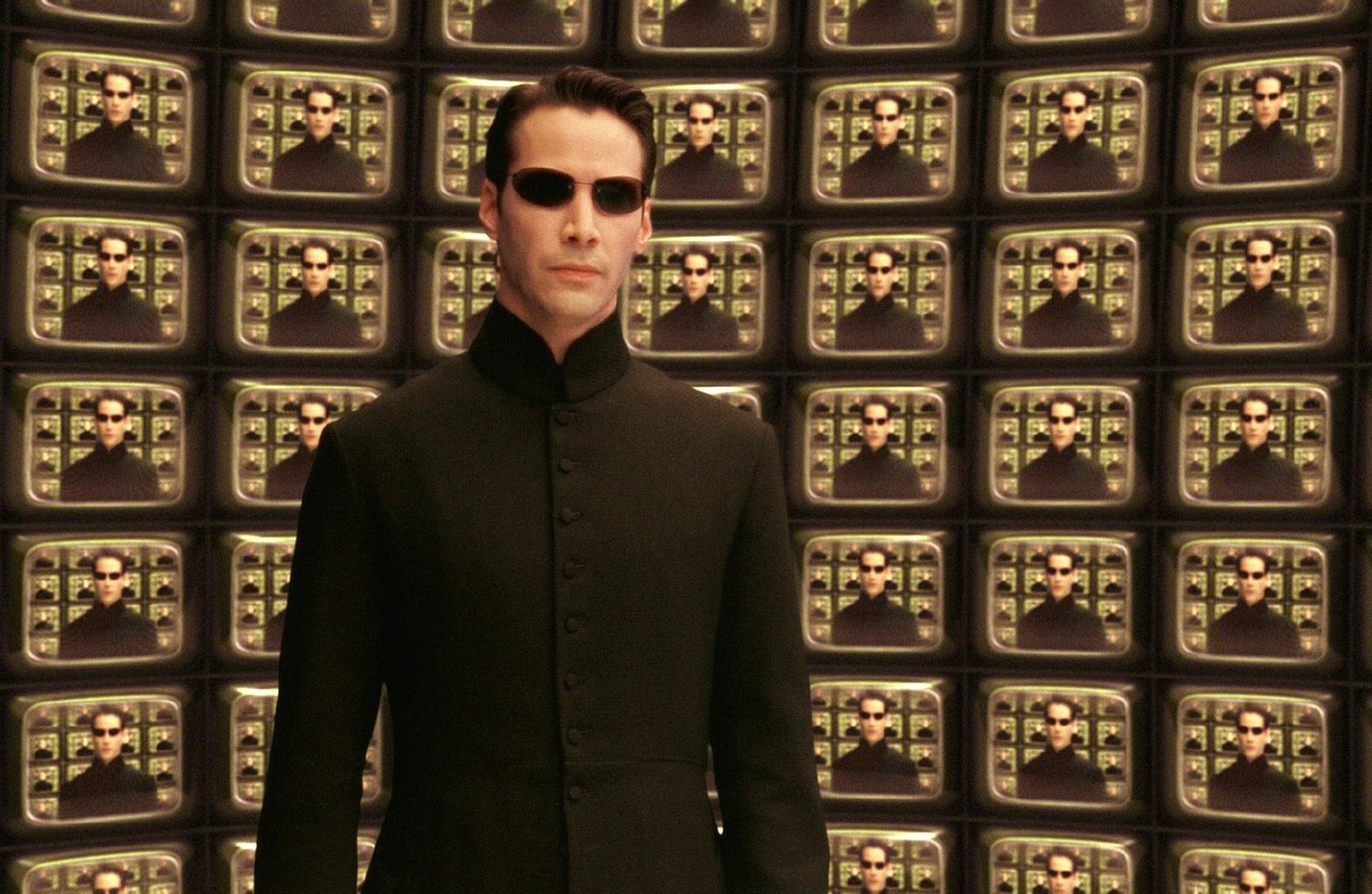

The Matrix (1999), and The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions (2003)

The Wachowskis actually wrote The Matrix before they wrote Bound. They initially conceived it as a comic book, but as they showed the script to their friends, they realized the material demanded more dynamic visuals.

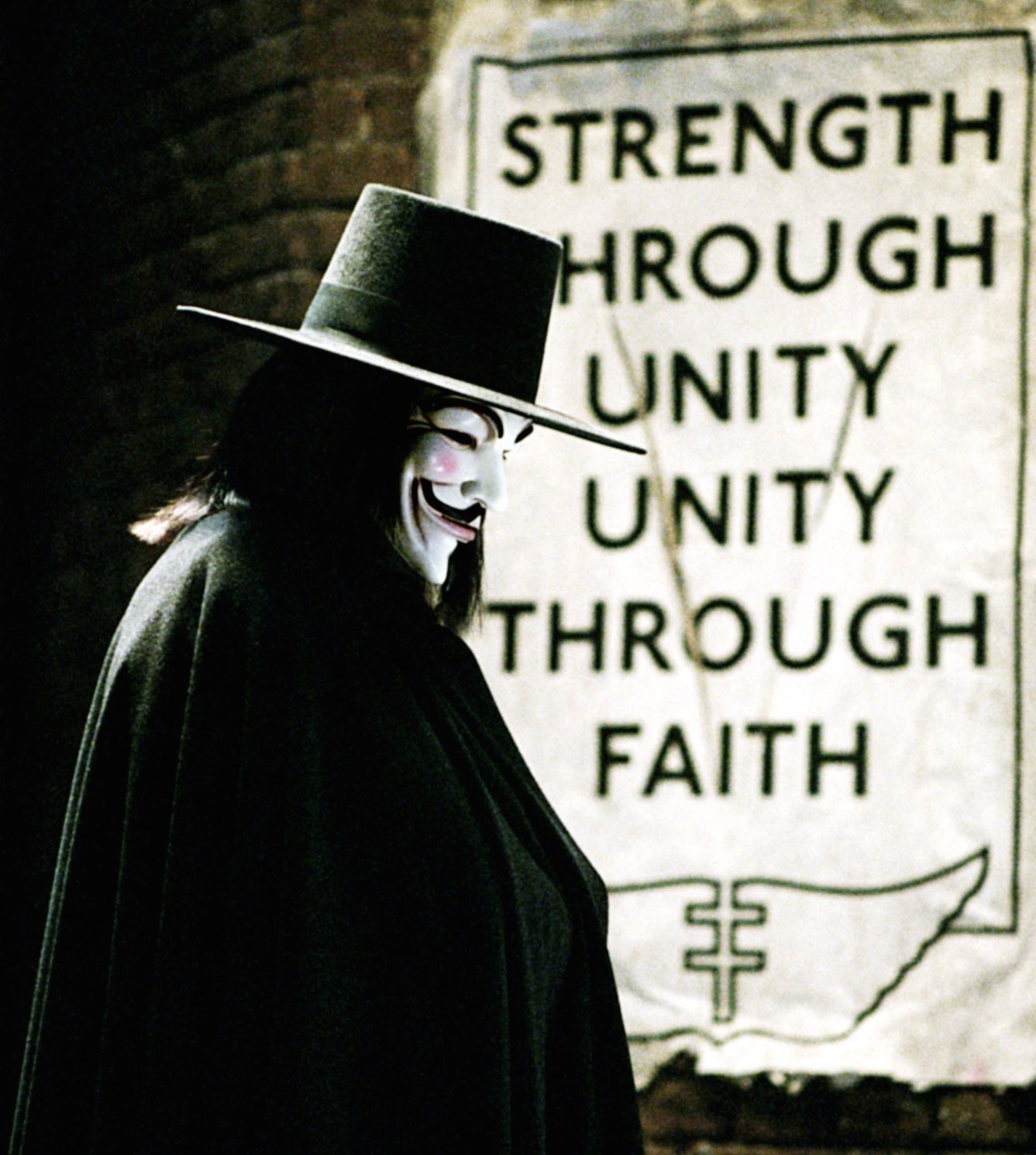

AW: Because we were involved with Warner Bros. at the time, we had this writing commitment to them. We were doing work for hire. We wrote a few different scripts, like this sort of Hitchcock-y thing about this guy stuck in a building. And then we did this version of Plastic Man, before the superhero thing hit. Oh, and then we wrote a version of V for Vendetta, and that was our commitment. Then after that, Bound came out, and we were like, "We gotta make The Matrix."

LW: This is the script that every single person rejected in this town. Everybody kept trying to change it. And everybody wanted us to blow The Matrix up.

AW: "Where is it? Where is the Matrix? Why don't you just blow it up?"

LW: "Like the Death Star?"

Instead, the movie blew up — modestly so at the box office, and becoming a true cultural force once it came out on DVD. Warner Bros. green-lit two sequels, which the Wachowskis shot back-to-back.

LW: Everyone was like, "Make the second [film] in the trilogy the exact same as the first. Why can't it just be the same? Why can't you just do it?" And we're like, "No, the point is that the opposite is true in the second one, and yes, it's gonna rub you the wrong way. But that's what we're interested in as artists." The second and third [movies] were the story for us. We explained to Warner Bros. what we wanted to do with the trilogy, and the first biggest thing was like, "Don't kill Neo! Just don't! You can't kill Neo! You can't kill Trinity! What are you doing?" It was never like somebody said, "Do what you want. Go forth, Wachowskis, and make whatever you want!"

AW: If we had been given that, the films would've been released a lot differently. We wanted [Reloaded] to come out, and then [Revolutions] to come out just as the box office was just starting to taper off, like, two months later. We don't want people to have to wait. And Warner Bros. was adamant that they wait a year. We got them to meet halfway, and it was released six months later.

LW: We were interested in resisting also the sort of financial structure that's around sequel-ization, which is essentially, you turn your story into a product that you just keep repeating. The whole concept of The Matrix was that we wanted to make the audience aware of what movies do to you, do to your consciousness, and to be somewhat compelled to follow Neo in the same way that he has to go through this struggle [over] his own relationship to his world. We wanted audience members to feel that struggle too. It wasn't ever meant to feel like a repeating "sequel-ized" thing. By splitting it apart, I think it raised that expectation.

V for Vendetta (2005) and Speed Racer (2008)

The Matrix Reloaded was a commercial sensation, grossing $742 million worldwide. But the film was seen as something of a disappointment, and by the time The Matrix Revolutions opened six months later, a lot of the wind had gone from the franchise’s sails — it grossed just over $300 million less globally.

Licking their wounds, the Wachowskis wouldn't direct a film for another five years. Instead, they resurrected and repolished their screenplay for V for Vendetta, ceding the director's chair to their longtime first assistant director James McTeigue. The film is based on Alan Moore's graphic novel about the violent struggle against a moralistic totalitarian regime in a futuristic England and contains some not-so-subtle echoes of the culture in post-9/11 America.

LW: We got letters saying, "This is un-American. You can't make this movie. Don't make this movie." We went into meetings and [executives] were like, "Really? You're gonna make this movie at this time?" You know, this was just a few years after 9/11. This is of course the time you have to make this movie.

After Vendetta, the Wachowskis decide to take on a long-in-development adaptation of the popular cartoon TV series Speed Racer — just about the least political movie imaginable. But the results proved to be just as polarizing, for a completely different reason. The movie ended up earning a very limp $93 million worldwide.

LW: Warner Bros. was at first gleeful that we were, like, doing a known entity that seemed like a family movie for kids. And then we started showing stuff, and they were like, "Oh my god. Oh my god." We were interested in cubism and Lichtenstein and pop art, and we wanted to bring all of that stuff into the cinema aesthetic. ... They were like, "Oh my god. Are you insane? What are you doing? This is the weirdest thing I've ever seen." And we're like, "Yes, that's the reason we're making it."

Cloud Atlas (2012)

After their first outright flop, the Wachowskis partnered with filmmaker Tom Tykwer (Run Lola Run) to co-write and -direct a wildly ambitious adaptation of David Mitchell's centuries-spanning novel. It featured actors like Tom Hanks, Halle Berry, Jim Broadbent, Hugo Weaving, and Hugh Grant in multiple, occasionally race-bent roles, and a twisting chronology that leaped from 1849 through the 23rd century. Though Tykwer and the Wachowskis cobbled together their budget independently, they still found themselves turning to the same major studio that had smiled upon practically their entire career to get their film done.

AW: Because it was independently financed, we had the leeway to bring it to different studios, and nobody wanted to do it. And so Warner Bros. [said], "Hey guys, what do you think of us?" They stepped up, and it couldn't have gotten made without them.

LW: Cloud Atlas will probably be the film that we're remembered for because of, I think, the unique way it touches people. I mean, people, they like The Matrix — "Oh, it was cool" — but it doesn't necessarily change their lives. We get letters from people who have gone through life-changing decisions because of that film. And that was probably the hardest film to get made. It was just agony to get that film finally green-lit and to get the cash. I mean, in the end, we didn't even get all the cash. Basically, we put in our own money to finally get over the last budget hurdle.

Jupiter Ascending (2015)

After spending a decade adapting other people's material, the Wachowskis returned to an original story for their latest feature film, an effort to make something more straightforward and lighthearted than the complex and difficult Cloud Atlas. It's about a young cleaning woman named Jupiter (Mila Kunis) who falls in love with a genetic hybrid space warrior named Caine (Channing Tatum) after learning she is the exact genetic double of the former queen of the galaxy.

LW: We went to Warner Bros. and we said, "Look, we want to make something lighter." And we showed them the script, and they were super enthused. We hadn't done a romance in years, and we had never made a fairy tale. So we were like, "Can you make a modern-day fairy tale in the way you can make a modern-day science fiction story?" The tone of Star Wars has kind of gone away a little bit from our movie experience, and we were wondering, "Can you capture that sort of playfulness again?"

The Wachowskis’ sense of playfulness collided most directly with their sense of artistic ambition in a scene in which Jupiter and Caine are chased through the skyscrapers of Chicago by a rampaging alien horde.

LW: [On] Willis Tower, there [is] this one moment in the summer when the sun bounces off the sky, hits the lake, and reflects up before it breaks the horizon. The sky is this incredible indigo, violet blue. And the city is still very orange from the “L” tracks and all this light. It's extremely beautiful, and it has a romantic quality.

AW: Then as [the sun] breaks the horizon, it's just blue sky.

LW: We take [cinematographer] John Toll up to the top of Willis Towers, [and] we're like, "Look at this. Isn't this amazing?" John's like, "Oh my god. This looks incredible. Should we shoot like a kiss?" And we're like, "No, we want to shoot the chase." The blood just went out of his head. And we wanted to shoot it for real, which means we wanted people on helicopters. … John Toll was looking at his watch, and [the light lasts], like, six minutes. And so we basically [filmed] a shot a day [in that scene] for the entire summer. Woke up at 3 a.m., got everyone ready to shoot basically 5:30 to 5:45. One shot, two shots maybe if you're lucky, every day for the summer to get that chase.

This time, however, the Wachowskis' expansive ambition appeared to hit a wall it could not quite scale. Jupiter Ascending was supposed to open last summer, but Warner Bros. decided to push it to February instead. It's a decision that still appears to rankle the filmmakers.

LW: This is part of another giant conversation about originality. When you think of all those great big continuing stories, like Raiders [of the Lost Ark], Star Wars, Terminator, Alien, Back to the Future, they all are original material written for our art form.

And the second thing they have in common is they're before 9/11. Post-9/11, we begin to have a different relationship to originality. We actually cultivate an attraction to things we know, to a derivative material. We want to see books turned into movies in a way we never wanted to before then, because, I think, we know the ending. Stories about the same character over and over are ultimately comforting in the way that a child feels comforted when they hear a bedtime story over and over and over. It's certain. You know what's going to happen. [The late film critic] Gene Siskel used to say he liked Indiana Jones because of the uncertainty of the fact that he was an original character. You weren't 100% sure it was going to work out. But he didn't like Superman because Superman was the same as Coca-Cola, and Coca-Cola was always going to be taken care of by the Coca-Cola Bottling Company.

Nowadays, people who write about movies are obsessed with derivative material in a way they never were before. And they crave it. They hunger for familiarity, and they actually have a suspicion of originality. And I think that the summer is one of the time periods when we are most hostile to originality as a culture right now. And that's why movies like Gravity have to be pushed away from the summer, when you can relax a little bit, and you can be a little bit more open when you're not in this sort of cacophony of competing familiarities.