Just about every movie genre has won Best Picture at the Academy Awards, from historical drama (Argo) to black-and-white silent romance (The Artist), war pictures (The Hurt Locker) to horror films (The Silence of the Lambs), fantasy epics (The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King) to toe-tapping musicals (Chicago), contemporary dramas (American Beauty) to period westerns (Unforgiven), unconventional comedies (Annie Hall) to crime thrillers (The Departed), Shakespeare adaptations (Hamlet) to sports flicks (Rocky), mysteries (In the Heat of the Night) to melodramas (Terms of Endearment), and even a family movie about the circus (The Greatest Show on Earth).

Just about every movie genre, that is, except science fiction — which is astounding. Because sci-fi is just about the most popular genre in filmmaking, accounting for as many as seven of the all-time top 10 grossing movies in the United States (if you count superhero films The Avengers, The Dark Knight, and The Dark Knight Rises as sci-fi). Yet, in the 86-year history of the Academy Awards, only eight sci-fi films have ever been nominated for Oscars' top prize, and none of them have won.

This year, however, one sci-fi film has a genuine chance at breaking the genre's Oscar losing streak: Gravity.

In one of the most competitive awards seasons ever, most Oscar prognosticators have pegged this year as a three-film race between Gravity, 12 Years a Slave, and American Hustle. But unlike every other sci-fi film that has ever been nominated for Best Picture, Gravity has won two key awards that have served as the most reliable bellwethers for Oscar gold: the Director's Guild of America award for Alfonso Cuarón, and the Producer's Guild of America award (in an unprecedented tie with 12 Years a Slave). Only three films that won both the top PGA and DGA prizes did not go on to win the Best Picture Oscar: Brokeback Mountain, Saving Private Ryan, and Apollo 13. And to gild this lily a bit further, two of those films were not the top Oscar nominees of their respective years. But Gravity is, with 10 nominations (a tie with American Hustle). With all of these markers signifying the depth and passion of Gravity's support within the industry, the film is better positioned than any science fiction film before it to win Best Picture.

And to be clear, while Gravity embraces a harrowing sense of realism in its depiction of an inexperienced astronaut stranded in space after a catastrophic accident, scientists will tell you that the film's treatment of the laws of physics and rules of space flight push well past the boundaries of established fact — so Cuarón could better explore his film's "what if?" conceit. His interest in using the trappings of science for great storytelling is pretty much the definition of sci-fi.

But the history of how science fiction arrived at this moment at the Academy Awards is also, in a way, the history of our attitudes toward sci-fi over the last century, as we shifted from treating the genre as something inherently unserious — part of a deeply ingrained cultural snobbery that has marginalized devoted sci-fi fans as "geeks" and "nerds" separate from the mainstream — to one of genuine artistry, relevance, and importance. Today, science fiction isn't just the most popular movie genre. It may just point to the future of cinema itself.

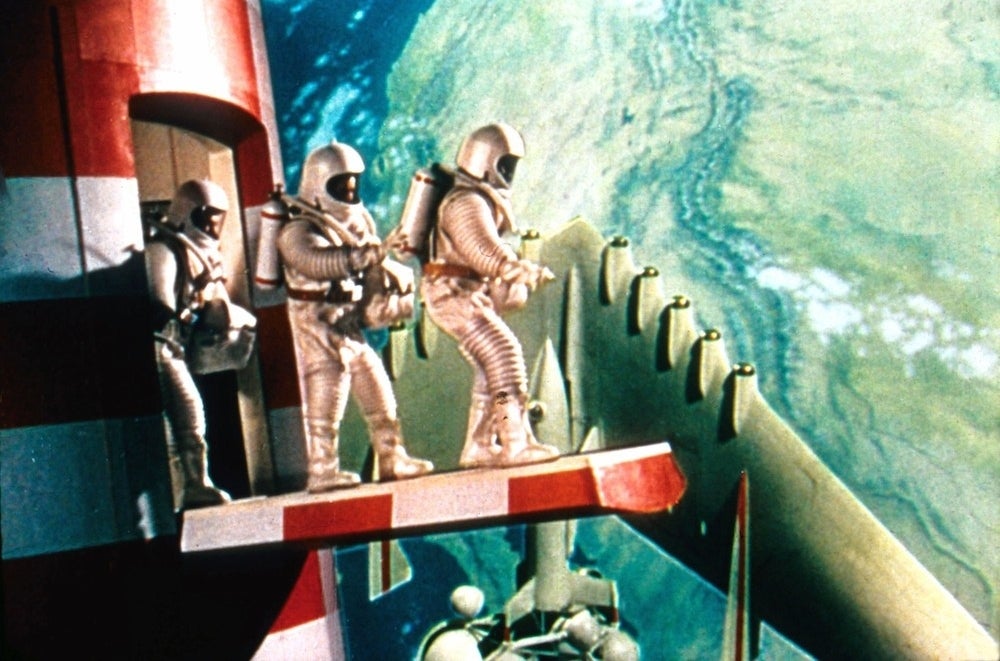

Maureen O'Sullivan and John Garrick in Just Imagine (1930), and George Pal's Destination Moon (1950).

Largely seen as the very first feature-length science fiction film, Fritz Lang's seminal movie Metropolis — released in the director's native Germany in January 1927, and in the U.S. a few months later — is a true and lasting masterpiece, influencing sci-fi filmmaking up to and beyond Star Wars and The Matrix. But in the first ever Academy Awards, which covered 1927 and 1928, Metropolis didn't receive a single nomination. The Oscars had barely even started, and they were already ignoring a movie that has since outlasted every film that won at that inaugural ceremony.

Four years later, a cutesy facsimile of Metropolis, 1930's Just Imagine, was the first sci-fi film to earn an Oscar nomination. It's a silly lark set mostly in a version of 1980 in which people's names have been replaced with numbers (J-21, meet LN-18), food has been replaced with pills, and cars have been replaced with personal planes. (A man from 1930, revived by modern technology, serves as the audience's introduction to this brave new future.) As a drama, it's a silly story with stock, two-dimensional characters that doesn't really explore the social satire inherent in its concept. (You can watch the whole film on YouTube.) But as a visual spectacle, it's a marvel — and was deservedly nominated for Best Art Direction at the 4th Academy Awards in 1931.

While other genre films like 1931's Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, 1941's Here Comes Mr. Jordan and The Devil and Daniel Webster (released at the time under the title All That Money Can Buy), and 1945's The Picture of Dorian Gray all took home Oscars, it wasn't until 1950 that a sci-fi movie won an Academy Award. Destination Moon, unlike Just Imagine, took its subject matter — what would it take for humanity to travel from the Earth to the moon? — seriously. (Well, OK, Woody Woodpecker does show up to explain space travel. It's not perfect.) There is even a sequence that predicts the plot of Gravity, when an inexperienced astronaut finds himself adrift in space, and a fellow astronaut uses an oxygen tank to retrieve him and bring him back to their ship. The imagery may not quite hold up today, but it was more than enough to win the Oscar for Best Visual Effects (the film was also nominated for Best Art Direction, Color).

But with sci-fi movies released pretty much exclusively as low-budget B movies — literally, the name for the second movie in a double feature, generally seen in the movie industry as populist grist for popcorn sales and not, you know, as art — the Best Visual Effects category became the best, and often only, chance sci-fi films had to win Oscars for the next two decades. Those winners included films like 1953's The War of the Worlds and 1960's The Time Machine, both from Destination Moon producer George Pal. And while these films are still striking even today, if the studios weren't going to take them seriously, the Academy wasn't about to either.

It took Stanley Kubrick, one of Hollywood's most serious filmmakers, to make the industry understand science fiction's full potential.

Today, it is an established fact that the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey is one of The Greats, a profound and challenging expansion of what filmmaking can even achieve. Forty-five years later, its Oscar-winning visual effects still stand up to scrutiny. But even though Kubrick was nominated for Best Director — the first time ever for a sci-fi film — as well as Best Adapted Screenplay for co-writing the film with author Arthur C. Clarke, 2001 did not earn a Best Picture nomination at the 41st Academy Awards. Instead, the Academy honored genuinely good films Funny Girl and The Lion in Winter, Franco Zeffirelli's lush and corny version of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, the long forgotten Rachel, Rachel (Paul Newman's feature directing debut), and one of the weakest films ever to win Best Picture, the over-the-top musical Oliver!. Kubrick would instead have to wait until his next film before he would break down the Best Picture barrier for science fiction.

Malcolm McDowell in A Clockwork Orange (1971), Carrie Fisher in Star Wars (1977), and Henry Thomas in E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982).

Based on the novel by Anthony Burgess, Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange does not automatically announce itself as a classic science fiction film, in so far as its depiction of a dystopian future is less keen on showing off the trappings of cutting-edge technology and more keen on exploding the audience's tolerance for and interest in "a bit of the old ultra-violence." But when Malcolm McDowell's Alex DeLarge is subjected to the "Ludovico technique" as a way of rehabilitating his sociopathic tendencies, the 1971 film also exploits the belief in the wonders of technology as a society cure-all, a classic sci-fi theme.

By the time A Clockwork Orange was released, Hollywood had itself gone through some convulsive changes, with the collapse of the old studio system and the rise of independently driven filmmakers willing to push the boundaries of long-held convention. It was in this relative cloud of movie industry chaos that A Clockwork Orange netted four Oscar nominations, for Best Editing, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Director, and — finally — Best Picture, something that a movie this provocatively weird and distressingly violent never could have achieved even five years earlier. Still, A Clockwork Orange didn't actually win anything.

Six years later, on the occasion of the Academy Awards' 50th anniversary, a science fiction film did break through, and Hollywood — and the Oscars — have never quite been the same. George Lucas' Star Wars took the sci-fi tropes of those B movies from the '50s and poured in a seriousness of purpose, playfulness of execution, and polish of production value. (There is an argument among hardcore sci-fi fans that Star Wars is more of a fantasy film rather than classic science fiction, but for the general public — and the voting body of the Academy — its embrace of space ships, laser blasters, aliens, and droids screamed "SCI-FI!") The insatiable audience enthusiasm for Star Wars — and its staggering box office returns — could not be denied by the Academy, and the movie earned a whopping 10 Oscar nominations, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Supporting Actor (for Alec Guinness), Best Original Screenplay, Best Score, Best Costume Design, Best Sound Mixing, Best Sound Editing, Best Art Direction, Best Editing, and, yes, Best Visual Effects. Perhaps even more astonishing, Star Wars took home the most hardware at the 1978 ceremony, with six Oscars, and a special award voted by the Academy's Board of Governors for Benjamin Burtt Jr.'s inventive sound design.

Star Wars did not, however, win any of the so-called "major" Oscars (for its screenplay, acting, directing, or Best Picture) — and neither did Steven Spielberg's Close Encounters of the Third Kind, which was honored with eight nods that same year, though not for Best Picture. (Most of the big awards that year went to Woody Allen's Annie Hall, which was itself something of a historic achievement for a comedy at the Academy Awards.) Five years later, Spielberg's E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial was another commercial and cultural juggernaut, this time with a huge emotional payoff that had audiences in tears multiple times over — not heretofore a common experience for a sci-fi movie. The film earned 10 Oscar nominations, including for Best Picture and Best Director, and in any other year, it would have likely been the favorite to win.

But 1982 was not like any other year — like 2013, in fact, it was a pretty fabulous year for movies, including Sydney Pollack's near-perfect comedy Tootsie, the hard-nosed legal drama The Verdict (featuring Paul Newman's best ever performance), the campy gender-bending musical Victor/Victoria, the Richard Gere–Debra Winger military romance An Officer and a Gentleman, the harrowing German WWII submarine thriller Das Boot, and Ridley Scott's visually sumptuous sci-fi mystery Blade Runner, a highly influential film that was, alas, also a box office bomb. It earned only two Oscar nods — for Best Art Direction and Best Visual Effects — indicating that commercial success was the key to science fiction films earning respect at the Oscars.

Amid that bounty of cinematic riches, meanwhile, the Academy punted, and pretty much gave everything to Richard Attenborough's aggressively stolid biographical epic Gandhi. E.T. had to be content with Best Score, Best Sound Editing and Sound Mixing, and — once again! — Best Visual Effects. And the Academy was content not to nominate a sci-fi film for Best Picture for another 27 years, after a pair of commercial and cultural triumphs demanded Hollywood pay closer attention.

Sam Worthington (as a Na'vi) in Avatar (2009), Sharlto Copley in District 9 (2009), and Joseph Gordon-Levitt in Inception (2010).

During the '80s and '90s, sci-fi films continued to bubble up at the Academy Awards. 2010, the oddly conventional sequel to 2001 (made with Kubrick's blessing, but not his involvement), earned five nods in 1984; Back to the Future, so unmistakably great, earned four nods in 1985, including one for Best Original Screenplay; and Sigourney Weaver earned the rare sci-fi Best Actress nod for her kick-ass turn in James Cameron's Aliens, which picked up seven nominations total and two wins in 1986. Quickly, a new pattern emerged: A sci-fi movie, especially a successful one, was likely guaranteed a nomination in at least one of the sound categories if not both, possibly a nomination for art direction and makeup, and most definitely a visual effects nod. If the movie was especially prosperous and/or directed by James Cameron — like The Abyss or Terminator 2: Judgment Day — it might also pick up nods for its editing, cinematography, and score. But by 1993, even though Spielberg's Jurassic Park was yet another commercial sensation, blockbuster box office alone was no longer enough to win over the Academy, and it picked up only three nods — and wins — for its sound and visual effects. (Though that was still a very good year for Spielberg; Schindler's List won seven Oscars, including his first Oscar for directing, and Best Picture.)

Then came something of a bleak period for lovers of great science fiction. As the Academy made clear it was interested only in the cursory celebration of technical achievement in sci-fi filmmaking, Hollywood focused on delivering even bigger, louder, and more expensive sci-fi entertainment. Mid-'90s films like Independence Day and Men in Black may be amusing diversions, even rousing ones, but they were studiously middle-of-the-road, designed to delight, but never provoke. They were still better, however, than sci-fi films like Michael Bay's Armageddon that felt like affronts to the very core of science fiction, and cinema itself. And yet, that film still earned four Oscar nods.

Thankfully, in 1999, The Matrix arrived. It may have been only a middle-range box office performer, but its breakneck visual and storytelling invention lit up sci-fi fans and the movie industry in a way that felt akin to Star Wars. Ironically, this was also the year Lucas launched that series' prequels with Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace. But when it came time to hand out Oscars for that year, The Matrix walked away with four — for Best Editing, Best Sound Editing, Sound Mixing, and Best Visual Effects — and The Phantom Menace went home empty-handed. While The Matrix had only won the same sort of awards sci-fi films had been winning for two decades, the industry couldn't help but observe a passing of the sci-fi baton — The Matrix took home nearly as many Oscars as that year's Best Picture, American Beauty.

Two years later, in 2001, The Lord of the Rings trilogy began its domination of the 74th, 75th, and especially 76th Academy Awards, with a total of 30 nominations and 17 wins, including Best Picture and Best Director for 2003's The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. It was an unthinkable achievement for a fantasy picture, redefining what was even possible for a genre that had, up to that point, arguably received even less respect from the Academy than science fiction. The Lord of the Rings films also pointed, however, to a new Hollywood paradigm of swing-for-the-fences, mega-budgeted franchise films based on established popular literature — making even less room in Hollywood for the notion of original science fiction cinema. The studios turned instead to comic books and toy lines for their blockbusters, and the Academy turned even further away from Hollywood, bestowing the lions' share of its accolades to darker, often independently financed motion pictures. Even the widely beloved sci-fi romance Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind earned just two Oscar nominations in 2004, winning for Best Original Screenplay.

On occasion, however, the world of Hollywood blockbusters and independent filmmaking did intersect, no more so than in the Dark Knight trilogy, helmed by auteurist indie director Christopher Nolan, first nominated in 2002 for the screenplay to his mind-crunching backward thriller Memento. Nolan's sense of epic scope and drive for intelligent, weighty realism electrified audiences most especially with 2008's The Dark Knight, which rocketed nearly to the top of the all-time domestic box office and placed the late Heath Ledger at the front of Best Supporting Actor race for his unforgettable turn as the Joker. Even though The Dark Knight made dozens of critics top 10 lists, and picked up PGA and DGA nominations, the Academy snubbed both the film and Nolan. Most blamed snobbery over The Dark Knight's comic book source material, but absent its superhero origins, the film is, for all intents and purposes, a brilliant work of science fiction. Likewise, Pixar's equally dazzling and celebrated 2008 film WALL-E was also denied a Best Picture nomination at the 81st Oscars, thanks largely to the Academy's bias against science fiction and animation. (Though animation is a broad filmmaking medium, not a specific genre, it's worth noting that no animated feature film has won Best Picture either.) These were movies that practically everyone loved and believed to be among the very best of the year, and yet, it seemed the Academy did not agree.

Rather than shrug and move on, however, the Academy took those double Best Picture snubs to heart, and the result was the biggest change at the Oscars in more than 60 years: the expansion of the Best Picture category from five films to 10 (and later, to a sliding scale of anywhere between five and 10). The expressed intention was to allow for films like The Dark Knight to earn a Best Picture nomination, and the subtext for many was an acknowledgement by the Academy that its membership was not properly honoring the kinds of movies most audiences are eager to see. Movies like, say, Avatar.

In truth, as the highest grossing movie of all time, there was little chance that 2009's Avatar was not going to be nominated for Best Picture, and James Cameron was not going to be nominated for Best Director. Its success was simply too overwhelming to ignore. But without the expansion of the Best Picture category, there was also little chance that 2009's District 9 — an independent sci-fi film from a first-time feature director and a no-name cast that picked up $115 million in the U.S. — would have ever earned a Best Picture nomination. And Inception, a box office behemoth with $293 million in domestic returns, would almost certainly have not earned a Best Picture nomination the following year. Thanks to the category's expansion, in just two years, the Academy doubled the number of sci-fi films nominated for the top Oscar, and it did so just as original sci-fi had started to reassert itself with audiences and critics in a massive way.

None of these sci-fi films, of course, won any of the "top tier" Oscars — in 2009, Best Picture went to one of the lowest grossing films in the category, Kathryn Bigelow's harrowing Iraq War thriller The Hurt Locker, and 2010 was a battle between the riveting Facebook drama The Social Network and the aggressively stolid period film The King's Speech. (Naturally, the latter won.) Still, it does appear that a dam of some kind has burst. The Academy's long-established disinterest in science fiction beyond the impressiveness of its visual effects and dexterity of its sound design is dissolving into a much more holistic appreciation for all the genre can offer at its very best.

The final frontier, of course, is Best Picture and Best Director. So, what would it mean if a sci-fi movie finally won Oscar's top prizes?

Joaquin Phoenix and Olivia Wilde in Her (2013), and Sandra Bullock and George Clooney in Gravity (2013).

If the Oscar tea leaves point to a certain Oscar win for Gravity — beyond its ear-ringing sound design and eye-popping visual effects, of course — it is for Cuarón's groundbreaking work directing the film. His process for making it, in fact, embodies the pioneering soul of science fiction: He and his team literally had to invent the filmmaking technology they needed to make their movie even possible. Like with his last film, the more morally complex (and more traditionally sci-fi) Children of Men, Cuarón's first principle of storytelling seems to be an unshakable desire to give the audience an experience it had never had before in a movie theater. And that desire also lives at the heart of the best of sci-fi — an eagerness to discover what lies just beyond the horizon of human possibility.

Another sci-fi Best Picture nominee this year, Spike Jonze's Her, also embraces that curiosity in some pointedly similar ways. Like Cuarón, Jonze not only uses the trappings of sci-fi to explore, at its heart, an emotional story of personal growth, he also points to where filmmaking itself can go. We've never seen anything quite like a heartsick man (played by the powerfully vulnerable Joaquin Phoenix) fall so totally, recognizably in love with a disembodied artificial intelligence, nor experience how that kind of relationship could ultimately play out. Watching it happen is a deeply weird experience, one that is just close enough to our own entangled relationship with technology to seem possible, but just unusual enough to make us wonder if this is really where our world is headed.

And that is a great place for the movies to live in. Of course, several films from 2013 that aren't sci-fi have lodged themselves in our collective psyches — from the historical urgency of 12 Years a Slave, to the talky simplicity of Before Midnight, to name just two. If Gravity loses Best Picture, and Her loses Best Original Screenplay (it just won the Writers Guild of America Award), they will be losing to worthy films deserving of our praise and attention. But even so, the film industry would do well to look to the examples of Gravity and Her, and the tradition of crowd-pleasing, envelope-pushing science fiction they have so richly and ably carried on.