The social graph is having a good year.

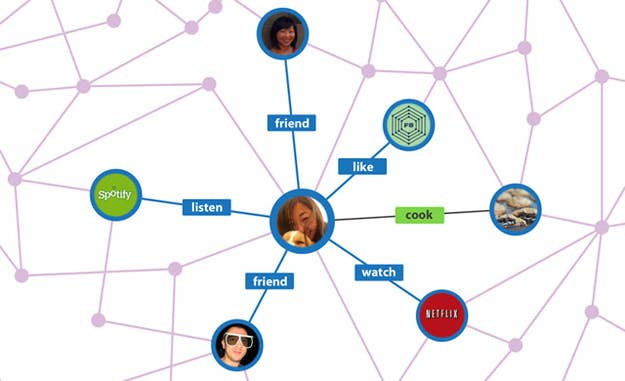

It got a spotlight in Facebook's unnerving roadshow video, but charts like this one have been guiding nearly every social network since the MySpace days. It's a simple idea — a rigorous, computer-friendly mapping of how a community fits together. But what you won't hear is that charts like this have been kicking around since the '30s, and they're more sophisticated than anything Twitter or Facebook would dare to roll out.

And if you're guessing at the future of social networks, that's a pretty good place to start.

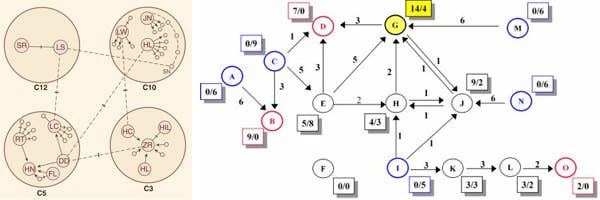

The four bubbles on the left are the world's first sociogram, penned by a physician named Jacob Moreno in 1932. He was examining an epidemic of runaways at the Hudson School for Girls: fourteen girls had run away in two weeks. Instead of examining each case individually, he mapped all fourteen girls on a graph, showing how the each case socially influenced the others, eventually leading to a social kind of epidemic.

As you may have noticed, it looks an awful lot like Facebook's social graph. Each person is a node, each friendship is a line, and the full map shows you where everyone stands. In the 80 years since, they've gotten a lot more complicated (e.g. the diagram on the right), but the basic ideas are all there, from status updates to joining and leaving groups. As any Klout user can tell you, the metric of "social influence" is still alive and well. And for anyone skeptical about the social graph, it's a powerful reminder: people have been at this for quite a while, and modern social networks are barely scratching the surface.

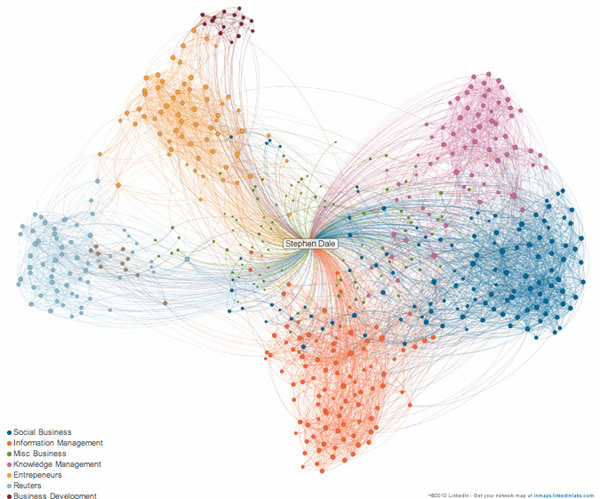

As a result, most sociologists are unimpressed by the modern social graph, in Facebook and elsewhere. When I presented the idea of Facebook as a sociogram to James Moody of the sociology journal Social Networks, he thought Zuckerberg & Co. weren't sophisticated enough to make the cut. "It’s better to treat Facebook as a type of social communication/media tool. That taps a dimension of social networks, but it's neither the end of networks nor necessarily their most interesting feature."

But that just means there's a long way to go. When Facebook started, it had to be simple. It needed to attract new users, and that meant as little clutter as possible, Ever since then, they've been gradually piling on features, getting closer to the intricate graphs most sociologists work with. Both sociologists and techies are aiming for the same thing, a comprehensive mapping of human relationships. The sociologists have a head start, and they don't have any users to slow them down, but there's plenty of reason to think they'll end up in the same place.

As of right now, Facebook doesn't support different kinds of friendship, or attribute mapping, or emotional transactions more complicated than "Like" — but as the social graph develops, it's easy to imagine a website that does, whether it's Facebook circa 2015 or the second coming of Friendster. And when it happens, they'll have plenty to work from.