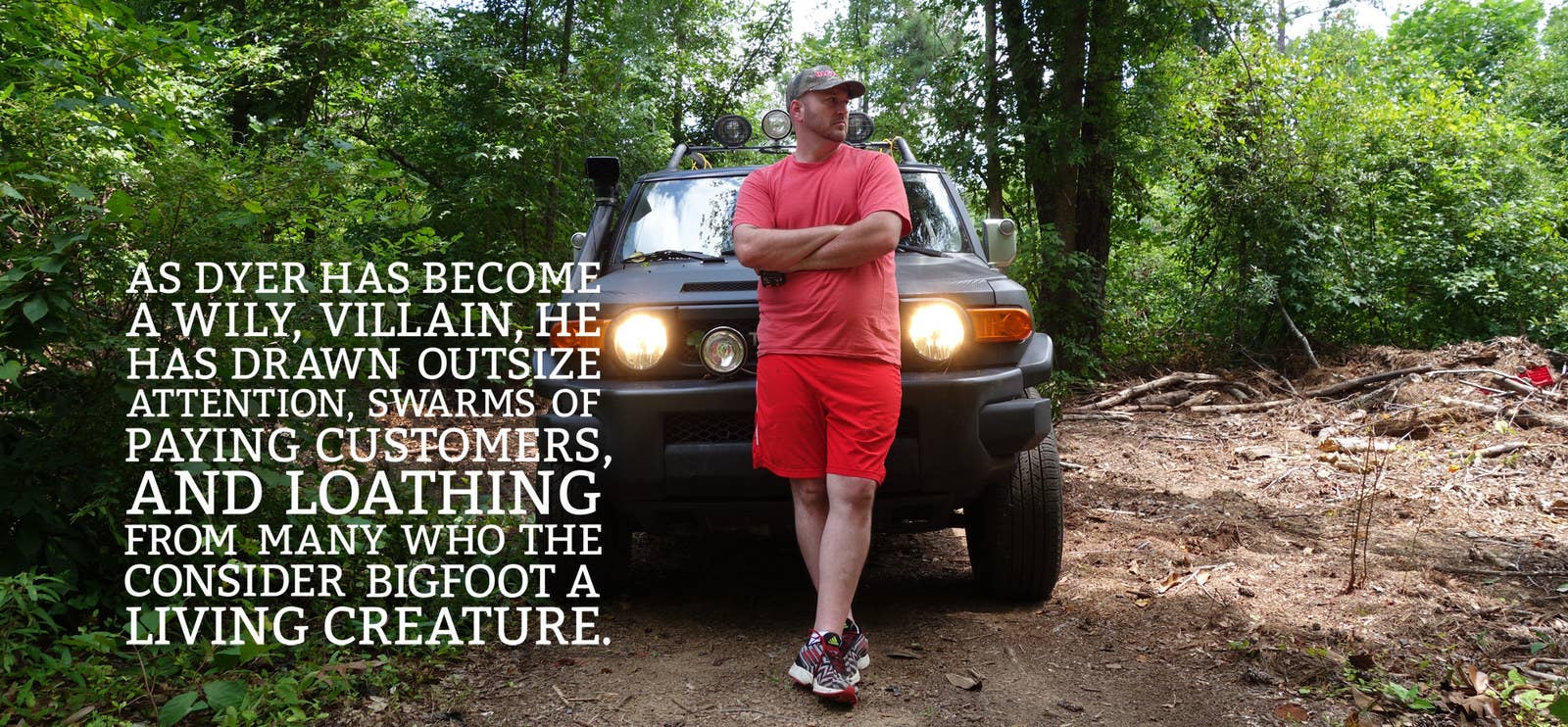

It’s a sweaty July day, and Rick Dyer is in his tank-like Toyota, barreling down a highway just south of Atlanta. It’s a comically oversize SUV, with a rack of roof lights and an exterior wrapped in flat-black vinyl. If Batman drove a Jeep, it would look like this.

Somewhere near the turnoff for a Christmas tree farm, Dyer abruptly turns into a sloping grassy median, then into a field of knee-high weeds beyond the road, then down a narrow dirt trail, where, after rumbling over an impressive heap of felled trees, we arrive at a small clearing just on the other side of a trailer park. Dyer, 37, is wearing a red T-shirt, red gym shorts, and a camouflage hat embroidered with a Bigfoot logo. His neatly trimmed beard frames a mischievous grin. “Let’s go do a Bigfoot investigation,” he says.

Moments later, we’re parked beside a trailer where a couple of boys are milling around a rusty grill. “Are you the one who called about Bigfoot?” Dyer asks. The pair looks confused. Soon, there’s a small gathering and Dyer explains that someone from a nearby trailer said that a Bigfoot attacked his car. “I went up there and checked it out, and his door from his car is ripped off,” Dyer says matter-of-factly. Someone asks what kind of car it was, and Dyer provides a make and model, and says a tow truck is on its way. If they see anything, Dyer tells them, please contact him through his website.

“What are you going to do if you find it?” a man in a basketball jersey and sunglasses asks.

“Well, I’ve already killed one,” Dyer says.

The boys look on in amazement as Dyer offers his bona fides. Look him up on Google, he says. They’ll read the accounts of how he bagged a Bigfoot. They’ll see the photos. Then, the boys scuttle away in search of the car with a missing door.

It’s an odd thing to witness such instinctive slipperiness. But Dyer is untroubled. To him, lying about one of the world’s most enduring wilderness mysteries is no different than a pro wrestler getting in the ring. “I’m an entertainer,” he likes to say. Or: “You can choose to believe my story or not.”

It’s been more than a half-century since a Northern California newspaper printed the headline that made “Bigfoot” a household name. In the decades since, no definitive proof of the large, ape-like creature that people also call Sasquatch (from Canada), Yeti (from the Himalayas), or Skunk Ape (from Florida) has surfaced. But the eyewitness accounts, the indistinct photos, the brief, blurry videos, the footprints — they’re as persistent as ever.

There are news stories about the latest sightings and YouTube clips purporting to show them. There are successful television series like Spike TV's 10 Million Dollar Bigfoot Bounty, which premiered earlier this year, and Animal Planet's Finding Bigfoot, now in its fifth season; on the channel’s website, there is a “Bigfoot Cam,” where “the search for Sasquatch goes 24/7.” There are countless groups and clubs and museums with names like North American Wood Ape Conservancy and Bigfoot Discovery Project. There are self-styled, expedition-leading Sasquatch “hunters” and online radio talk shows and origin theory-peddling experts.

Against this backdrop, Dyer’s anything-goes hustle means business. He markets himself as a “master tracker” after all, a label that is prominently attached to the short-sleeve camouflage button-up he wears.

As we get in the Toyota, Dyer delivers a full-throated roar. “They’re going to be talking about that for weeks and weeks and weeks,” he says. And yet, this off-road adventure is nothing compared to Dyer’s big hoaxes.

Over the last 50 years, allegations of devious men using wooden feet and fur suits have cast a long shadow over the Bigfoot phenomenon. But Dyer’s dark talents are rare. He’s an admitted serial hoaxer with a chameleon-like ability to cultivate a new persona for each gambit, from bumbling neophyte to Sasquatch evangelist to P.T. Barnum-like showman. “In the annals of Bigfoot hoaxers, he’s earned himself a place in the hall of fame,” says Benjamin Radford, the deputy editor of Skeptical Inquirer and author of Hoaxes, Myths and Mayhem.

As Dyer has become a wily villain in the Sasquatch scene, he has drawn outsize media attention, swarms of paying customers and fans, and loathing from the many people who consider Bigfoot a living creature. After a hoax earlier this year, a petition was posted on Change.org demanding that he be charged criminally (he has not been). Loren Coleman, the cryptozoologist and author of Bigfoot! The True Story of Apes in America, describes Dyer as a “disgusting phenomenon” who just won’t go away.

For this second variety of Bigfooter, the search for Sasquatch is a serious endeavor. They are modern-day explorers, amateur investigators, and even academically credentialed researchers who have sought to not only bring science to Bigfoot, but Bigfoot to science. While no bones, body, or DNA have been discovered, they argue that there is considerable circumstantial evidence that Bigfoot is real.

For these dedicated few, Rick Dyer is more than an entertainer — he's a danger to a field of study that already has credibility issues. That they all toil under the same big tent is one of the great oddities of a subculture that is as crowded and fractious as ever, one that can seem like an amalgam of a cult and an earnest explorers club, with competing camps of believers and skeptics, hoaxers and hunters, self-appointed experts and serious-minded scientists, all seeking to advance, in their own peculiar way, the mystery of Sasquatch.

Jeffrey Meldrum’s office is on the second floor of a plain redbrick building in Pocatello, a college town in southern Idaho. It’s cluttered with books about anatomy and biomechanics, evolution and mammalogy. There are plastic skulls and wooden skulls, framed images of the surreal-looking red-faced uakari, and a silverback gorilla, his arms aimed piercingly straight into the ground.

Then, there is the Bigfoot stuff: hundreds of plaster foot casts believed to be Sasquatch, sitting on the floor, scattered on a work table, crammed into shelves. There are cartoons and tiny statues, books and envelopes labeled “hair.” Meldrum, 56, with a white beard, is wearing a black T-shirt with a pair of green eyes that stare back at me. “Sasquatch as seen through night-vision goggles,” he explains.

Against the far wall is a life-size image of the most well-known Bigfoot of the modern era: “Patty,” a nickname derived from the man who filmed her, an out-of-work cowboy named Roger Patterson. In a few dozen shaky seconds in 1967, Patterson captured her on film in the remote woods of Northern California striding along a creek bank. The footage, which he shot with the help of a rancher named Bob Gimlin, has remained an obsession, endlessly watched, dissected, debated.

An anthropologist at Idaho State University whose work on Bigfoot garnered a rare, significant endorsement from famed primatologist Jane Goodall, Meldrum specializes in the evolution of primate movement — he’s sometimes called “the foot doctor." His scientific pursuit of Bigfoot began in the late 1990s with a brief question: “Is there a biological species behind the legend?” In the years since, Meldrum has analyzed hundreds of footprints, examined reams of supposed hair, and developed a working hypothesis. He’s trekked across dozens of miles of Western wilderness, where he says he’s had his own Bigfoot encounters, and in 2006, he published Sasquatch: Legend Meets Science. In addition to Goodall’s praise, the book won support from the pioneering field biologist George Schaller, who wrote that Meldrum “disentangles fact from anecdote, supposition, and wishful thinking” and has “done more for this field of investigation than all the past arguments and polemics of contesting experts.”

The year after Meldrum’s book was published, he developed a scientific name and set of characteristics for the creature’s mythically massive footprint; it is, he says, one of the few peer-reviewed papers supporting the existence of Sasquatch to appear in mainstream academic literature. A few years later, he founded a peer-reviewed journal that publishes Bigfoot research. Among his current collaborations is a project that would use a drone to fly over suspected Sasquatch habitat in the United States and possibly Canada.

Meldrum’s research has made him a lonely figure in academia and an unlikely public face on this side of the Sasquatch phenomenon. He’s become The Bigfoot Guy — the level-headed, go-to scientific authority for conference organizers, countless documentary filmmakers, and on-deadline reporters who may not know the first thing about Bigfoot but are calling to ask about someone named Rick Dyer who claims to have killed one. The two know of each other, and they’re not friendly.

When Meldrum was a kid living in Washington State in the 1960s, his father, a grocery store manager at Albertson’s, took him to see the documentary that featured Patty. He was taken with snakes, insects, dinosaurs — anything natural history-related — so it didn’t take much to get him to the Spokane Coliseum, where it was showing. Meldrum sat transfixed as Patty’s slow-motion image meandered across the screen. “The notion that there might be a caveman stomping around out there was fascinating to me,” he recalls. For him, there were no questions of authenticity. “It was like, 'Here it is. Wow.' It was a mystery to be explored.”

At the time, Bigfoot was just beginning to lurch into the American imagination. Meldrum had no idea about the footprints found a decade before that produced the Bigfoot moniker. Nor did he know that for the Hoopa in California, for the Anasazi in the Southwest, and for many more, stories of wild, hairy men in the woods had been told for generations. The term “Sasquatch,” after all, was derived from the Salish tribes of British Columbia.

In 1993, Meldrum got a call from the prominent cryptozoologist Richard Greenwell. A television production crew in Northern California had been filming b-roll when they picked up what looked like a Sasquatch; when the crew wanted some expert opinion, they called Greenwell, who wondered if Meldrum wanted to tag along. Meldrum didn’t think much of Bigfoot anymore, but he wasn’t a strange choice: For years, theories had been floated that perhaps the Yeti was related to a giant ape that once lived alongside prehistoric humans. The creature was believed to have gone extinct, but perhaps it survived “in refuge areas,” as the primatologist John Napier suggested in 1973. Who better to examine the evidence than a primate expert?

Meldrum was skeptical, but he agreed. “I thought it would be an easy exercise in exposing the zipper,” he says. “Instead, I kept finding these different things that were quite compelling.” It was grainy video, and it was night, but he could see how its foot bent when it walked. He could see how the hair hung down from its arms, like an orangutan. They were able to determine its height too: more than 8 feet tall.

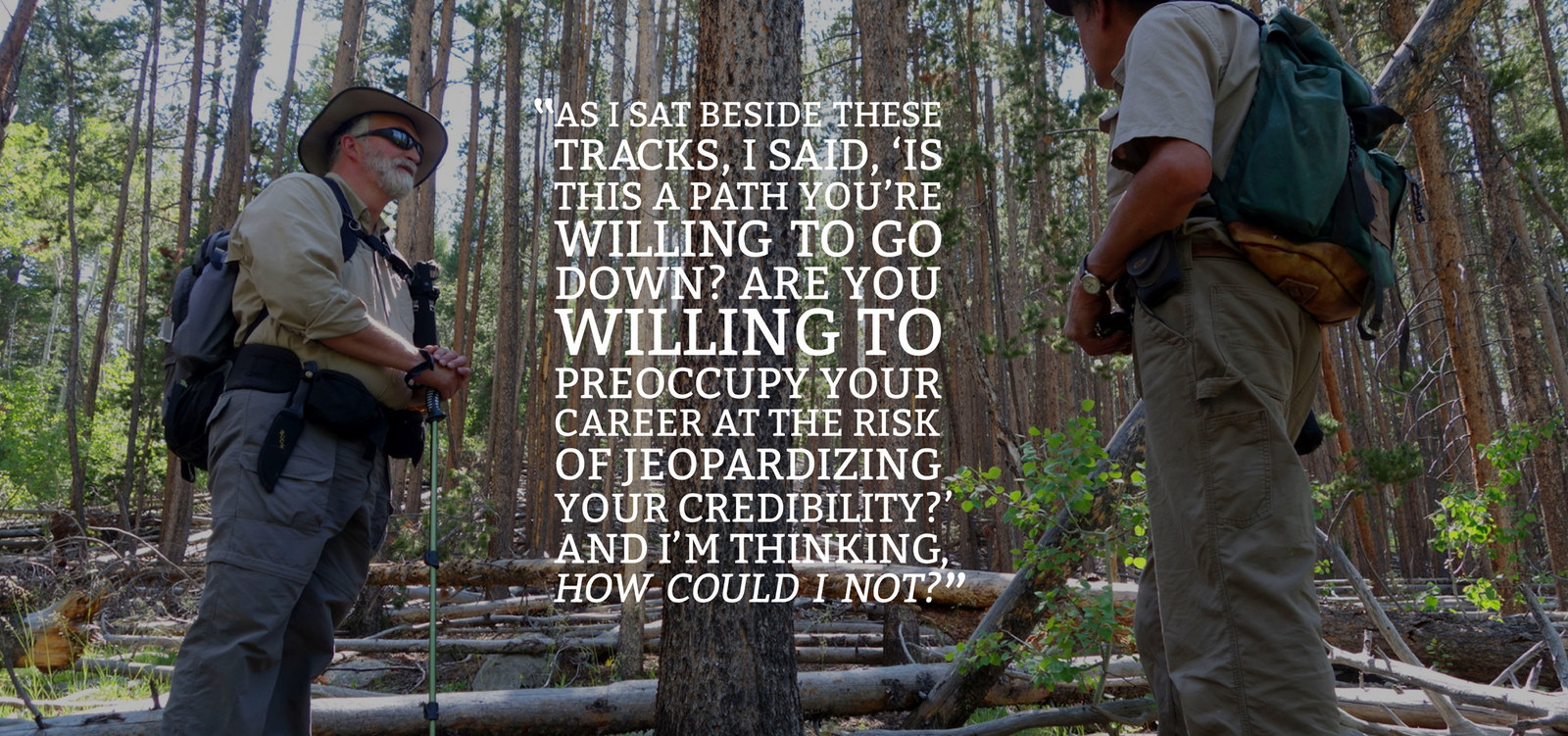

Then, after visiting the late Grover Krantz, the eccentric Washington State University anthropologist who was among the few academics to conclude that Sasquatch existed, Meldrum got out into the field. For the first time, he examined what were purported to be fresh tracks. They were 14 inches; there were a few dozen of them, pressed into the muddy foothills outside Walla Walla in eastern Washington, on the shoulder of a restricted-access farm road. When Meldrum bent down, he was astonished. He could see the telltale traces of a living foot, a foot where dozens of bones and joints appeared to be interacting with the ground beneath it. “I could see tension cracks, push-off ridges,” he recalls. “I could see toe slippage, dragging.”

This was not what happened when a blocky piece of wood was stamped in the mud, Meldrum thought. If it were a hoax, it would have been executed by someone who understood the subtleties of foot anatomy.

“As I sat there kneeling beside these tracks, I said, ‘Is this a path you’re willing to go down? Are you willing to preoccupy a portion of your attention, your career to this question, at the risk of jeopardizing your credibility?’ I’m looking at these tracks and I’m thinking, How could I not?”

Rick Dyer and I are driving around an affluent black suburb of Atlanta, a neighborhood of large lots, elegant brick homes, and golf course lawns. In a driveway, he sees what he’s looking for: a black luxury SUV with low mileage and a low asking price. Dyer, who’s wearing his camouflage Bigfoot hat and matching “master tracker” button-up, is looking to flip it — this is his day job — and he’s sized up the seller immediately. “The oil is full but he doesn’t know what a jumper cable is,” he says. “What you’re looking at is the perfect person to buy a car from.”

After a quick drive around the block, Dyer tells the seller that the transmission is shot. It needs a rebuild, and thus, the $2,000 price tag just doesn’t make sense. The two men haggle for a moment, and eventually settle on $1,400.

Afterward, I ask Dyer what he’ll make reselling it.

“$5,500,” he replies.

“Does that include what you’ll pay for a new transmission?”

“It doesn’t need one,” Dyer says, chuckling. “But it does need some transmission work.”

It can be difficult to untangle basic details about a man who lies for a living and seems to have no connection to his past. I ask, for instance, if he’ll put me in touch with his sister, and, in a text, he says there’s zero chance she’ll talk to me. I ask who his oldest friend is, and he connects me with a chicken farmer in Virginia named Jackie Pridemore. Pridemore tells me that the two met a couple of years ago, after he wrote a rap song about Dyer’s Bigfoot exploits. Dyer says his mother is a country music songwriter, but he can’t tell me who she is because the “haters” in the Bigfoot scene will go on the attack. His car has been vandalized, he says, and a variety of pranks have been orchestrated against him and his clique of Bigfoot friends.

Dyer’s peculiar enterprise seems driven in part by money — he claims to have earned hundreds of thousands of dollars — though as Loren Coleman explains, there just isn’t that much to be made from Bigfoot hoaxing. (“It’s not like a stock market scheme,” he says.) Attention seems to be Dyer’s motivating force, and he is relentlessly on-message: The Bigfoot scene is filled with self-serious crybabies, and Rick Dyer might be a hoaxer, but he only hoaxes because, like Santa, Bigfoot brings joy to people. And really, you should listen to Rick Dyer because Rick Dyer is the only person to have ever killed a real live Bigfoot.

Dyer embraces the confusion. “I want people to write that I’m very deceptive, that I dance around stuff,” he says. “I want people to write all kinds of shit. I want people to write that I don’t have a body, so that when that time comes and I do, then it’ll make the people who said I didn’t look like idiots.”

Unlike Meldrum, Dyer was never a Bigfoot-phile. When he was a boy with a stutter growing up in Stockbridge and attending Christian school, he had never seen the Patterson-Gimlin film, as the grainy Patty footage came to be known, or heard of the persistent rumors surrounding it — that the fur suit had been created by the Hollywood makeup artist behind the original Planet of the Apes franchise, for instance. Nor had Dyer heard of Ivan Marx, the alleged hoaxer behind the 1976 film The Legend of Bigfoot, or of one of the other (alleged) classics: that the original “Bigfoot” prints from Humboldt County, California, came from a pair of carved wooden feet owned by a man named Ray Wallace.

Mainly, Dyer says, his interests, after a stint in the Army, were traveling — he went to Thailand, to Mexico, to Japan — and women; with three, he has seven children. But in March 2008, not long after he quit his job as a corrections officer at a state prison, Dyer’s first hoax was born. It happened while he and a friend, a police officer named Matthew Whitton, were hiking in Tennessee. It wasn’t exactly inspired. “I said, ‘Hey man, I saw Bigfoot,’” Dyer says he told Whitton. “He said, ‘Me too.’ We didn’t. I said, ‘Let’s do a Bigfoot hoax.’ He’s like, ‘OK.’”

They built a cheap website and started a YouTube page, where he and Whitton posted videos and advertised expeditions and gear. They were “the best Bigfoot trackers in the world,” they claimed and, as Dyer put it in one video, “they had some very compelling evidence” that would “change everything you knew about Bigfoot.”

“We thought we’d get a couple of hundred views,” Dyer says. “But it took off.”

After appearing on a Bigfoot radio show, Dyer and Whitton were in touch with a man named Tom Biscardi. Biscardi is a brash, self-described “real” Bigfoot hunter who is from Brooklyn, but now lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. He is also an accused hoaxer and the proprietor and “team leader” of the California-based Searching for Bigfoot Inc., which investigates sightings, and, through its website, sells all manner of Bigfoot paraphernalia. In Dyer’s telling, Biscardi told him that he knew they didn’t have a body. “But we can make a lot of money,” Dyer recalls him saying. In Biscardi’s version, Dyer’s the con man. “He’s a motherfucker,” Biscardi says.

"DO YOU KNOW HOW HARD IT IS TO FIND GOAT BALLS?"

Dyer and Whitton set about building a fake body; the plan was to present a staged, video-recorded autopsy in the tradition of the famously hoaxed alien autopsy film of the 1990s, Dyer says. He spent a few hundred dollars on a rubber costume, and filled it with a macabre mix of animal bones and innards: There were pig intestines. There was a cow jaw. For the genitalia, they went to a slaughterhouse. “Do you know how hard it is to find goat balls?” Dyer says. The body was placed in a deep freezer, which was slowly filled with water, then switched on. For an accompanying DNA analysis, Dyer found an opossum on the side of the road. He carved off a sliver and bled on it; the hope, he says, was to have the analysis come back as human.

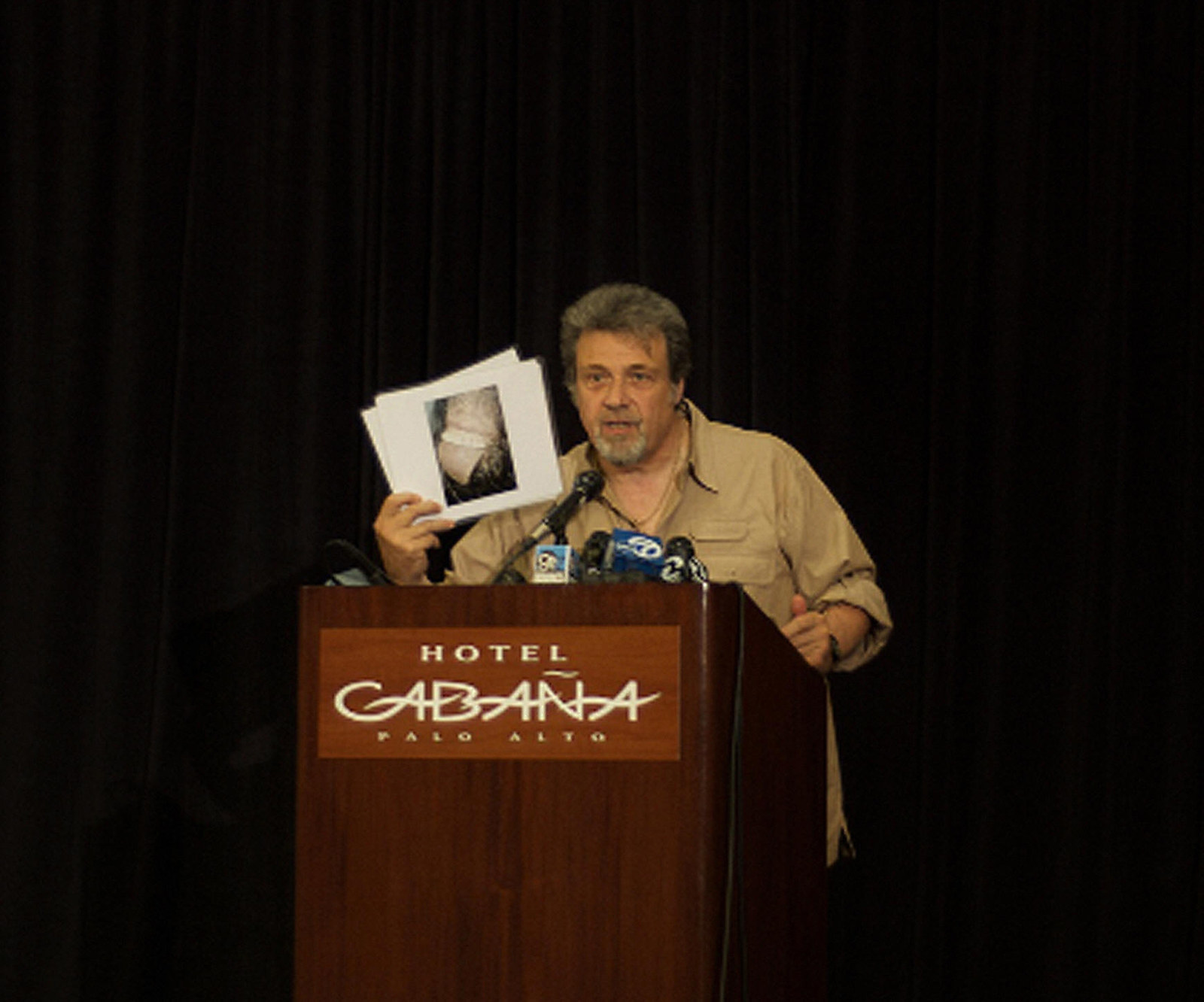

In Dyer’s telling, Biscardi liked what he saw, and agreed to pay $50,000 for the finished product; Biscardi says that he never actually saw the body. “They gave me a piece of intestine,” he recalls. In the parking lot of a redbrick county courthouse in suburban Atlanta, Dyer and Whitton were given $50,000 in cash, and the freezer was loaded into a U-Haul and driven to an out-of-state “safe house.” Then, the pair flew to California, where Biscardi scheduled a news conference for noon on Friday, Aug. 15, 2008, at the Cabaña Hotel in Palo Alto. In a press release, Biscardi offered a few tantalizing details: Dyer and Whitton found the creature in the woods of north Georgia. It weighed more than 500 pounds. DNA tests were being conducted and the results would be presented at the news conference.

This last detail, says the author Benjamin Radford, was key to selling the hoax: No one had ever dangled a promise of that modern scientific marvel, DNA, before an audience desperate for direct evidence. An onslaught of media attention followed. Most was dubious, but there was plenty of it. Stories appeared not just in the local media, but in Scientific American and the New York Times, on CNN and NBC. “It was pretty fucking intense,” Dyer says.

It’s a cold, damp summer night deep in the Wyoming wilderness, and a night vision scope is pressed to my right eye. In the distance, the flickering black-and-green tree line looks like an '80s-era computer screen. Beside me, Meldrum’s research partner, the wiry wildlife biologist John Mionczysnki, is sitting on a small canvas stool, accordion in hand, playing a lullaby-like Scottish folk tune, which he swears is a soothing animal lure. Periodically, he trades his squeezebox for a portable floodlight and scans the foliage. In front of us, Meldrum is stretched out on a sleeping bag, peering through binoculars into the inverted darkness.

We’re here in this boggy, bug-infested section of Wyoming because there have been Sasquatch stories dating back more than a century — everything from visual eyewitness accounts to elk hunters reporting what’s been described as Bigfoot behavior: something lobbing rocks in their direction. Earlier in the day, they spent a couple of hours trudging through the area, doing what they often do on these trips. They survey. Meldrum looks for traces of Sasquatch: footprints, hair, scat. He finds turned-over rocks — most likely a bear — and a long line of elk prints. He finds tufts of hair snagged on a branch. “Deer or elk,” he says. Mionczysnki, who’s also a botanist, catalogs the flora. He notes the sorts of things that might satisfy the appetite of a large mammal — the pocket gophers, the carbohydrate-rich sedges, the limber pines and their high-calorie pine nuts, the lily ponds and their fish and insects and frogs, the thistles, a favorite of gorillas.

This is a fairly routine night of research for Meldrum. Fifteen years ago, he had been so impressed with the footprints in Washington State that he ignored his inner pragmatist and decided to seriously pursue the question of whether an ape-like creature could have made them. He was untroubled by the lack of additional evidence: bones of uncommon top predators are rarely found and the fossil record is notoriously patchy. Plus, the discovery of new mammals — some of them large — is not unheard of. In 1994, a rare species of ox was located in Vietnam. The following year, a breed of prehistoric horse was found roaming in Tibet. In 2001, the three-toed pygmy sloth was identified in Panama.

"IT'S SO EASY TO SAY, 'OH, IT'S JUST A MAN IN A FUR SUIT' UNTIL THEY SEE IT BESIDE A MAN IN A FUR SUIT."

So Meldrum’s search began in earnest. One element was a close examination of plaster foot casts and footprints that appeared credible. He thought enough of them that he told me, “It’s the most elegant adaptation of a giant bipedal” — or on two legs — “primate living on the ground in steep mountainous terrain.” Another still-ongoing project has been a collaboration with a costume and robotics designer to reexamine the footage he first saw as a young boy in Spokane. “It’s so easy to say, ‘Oh, it’s just a man in a fur suit,’” he says. “Until they see it beside a man in a fur suit.”

Finally, there was fieldwork, and the hope of acquiring DNA from hair, or perhaps shooting some high-quality photos or video. And that required money. Bigfoot was hardly a burgeoning research subject in academia, though. As University of Florida anthropologist David Daegling observed in Bigfoot Exposed, “Within the Ivory Tower, it is perfectly legitimate for a folklorist to pursue unicorns; for a biologist, it is a foolish commitment of resources.” (A letter circulated at Idaho State signed by more than a dozen colleagues complained that Meldrum’s work was “fringe science.”) So, like many Bigfoot searchers before him, Meldrum secured private funding. With money from a wealthy oil and gas businessman in Texas, a foundation in California, and others, he planned weeks-long expeditions to the remote corners of the West where, often with Mionczysnki, he spent many nights listening, watching, and waiting.

Meldrum has stories of encounters from trips like this. He was weeks into a month-long expedition in Northern California when, late one night, he heard something rummaging through his guide’s pack. The two men jumped out of their tents, but whatever it was disappeared. Not long after, Meldrum heard footsteps. “I could hear the pat-pat-pat coming right towards me,” he recalls. “It brushed against the fly of my tent and hit the pole.” He called out to make sure it wasn’t his guide, then leaped from his tent. As he chased after it, he could hear it splashing through a marsh, and when he pointed his flashlight at the mud, he could see a pattern: right-left-right-left. Each track was about 16 inches. Then, it vanished.

It’s a dramatic story, but it’s among the most compelling pieces of evidence from Meldrum’s expeditions. He’s collected no DNA, and he’s gotten no photos and no video. When I ask if this gives him pause, he tells me that a combination of variables (including bad weather) and the nature of the work — “You’re looking for a moving needle in a haystack,” he says — can make this an all too common experience in wildlife tracking. Based on the evidence he’s seen, he’s concluded Sasquatch is a living thing, a large, upright ape of which there are a couple thousand west of the Mississippi in Canada and the United States.

Sitting in our camp, the three of us look beyond a narrow, shallow creek, toward a large pine tree to which Meldrum has strapped a camouflage digital camera with a built-in motion detector. If a Sasquatch is going to appear tonight, he and Mionczysnki reason, it’s going to come from the area that they surveyed earlier in the day.

So we wait.

In the summer of 2008, Meldrum was among the first to weigh in on the hoax from north Georgia. Even before the Palo Alto news conference, during which Biscardi distributed a close-up photo of the teeth — “It’ll prove to you people that this is not a mask,” he said to the crowd — Meldrum told Scientific American that it looked exactly like the thing it was: “a costume with some fake guts thrown on top for effect.”

It took just a couple of days to unravel. In Dyer’s telling, it was over money. Someone at the so-called safe house wanted more, but Biscardi refused to pay, and, lest he be extorted, outed the hoax. In Biscardi’s version, he got a call from a costume maker who claimed that Dyer’s body matched their product. So Biscardi instructed his associate at the safe house to heat the slab of ice. “Seven hours later, they call me back and say it was a rubber suit with body parts,” Biscardi says. So he confronted Dyer and Whitton. “I say, ‘Is there anything you want to tell me?’” he recalls. “They say, ‘Oh no.’”

Biscardi says he contacted Fox News, and a wave of stories about the boys from Georgia followed. Biscardi pursed fraud charges, and though they were unsuccessful, Whitton was fired from the Clayton County Police Department. (He and Dyer are no longer friends, and Whitton couldn’t be reached for this story.) For Dyer, though, the event served as a strange entry point into a new hustle. People kept contacting him, wanting to go on Bigfoot expeditions, he says.

So Dyer obliged. He created a new storyline, and presented himself as a reformed hoaxer. “He said that he had seen Bigfoot, and that he was on a mission to redeem himself,” a documentary filmmaker named Morgan Matthews told the Canadian Broadcasting Company last year. (Dyer would later appear in one of Matthews’ films.) Dyer made T-shirts and hats, and he took people on what were little more than backcountry fishing trips that ranged from two days to two weeks in Tennessee, Texas, north Georgia, California, and beyond.

Among the people to contact him was Matthews, who was working on a project about Bigfoot hunters. And so began Dyer’s next hoax. It’s a convoluted tale that begins, of course, with the real killing of a real Bigfoot.

During the summer of 2012, Dyer and Matthews embarked on a week-and-a-half-long expedition in a forest on the edge of San Antonio. On the morning of the sixth day, Dyer says he awoke to the sound of bone crunching; he looked out of his tent and saw what he claims was a large creature with reddish-brown hair. It was, Dyer says, his moment of conversion to Bigfoot believer. “I was in shock,” he says. “I didn’t even think Bigfoot exists.”

Matthews didn’t respond to interview requests, but Dyer claims the filmmaker captured the encounter on a high-resolution camera. Dyer, meanwhile, says he got it on his cell phone. But they wanted more. So that day, Dyer says, he and Matthews bought a rack of ribs from Walmart and Dyer nailed it to a tree at their camp. Then, they waited. Around 11:30, Dyer says he heard footsteps and twigs snapping. He jumped out of his tent and, with Matthews chasing him, ran after the creature. Dyer had his .30-06 hunting rifle; Matthews had his camera. In the end, Dyer says, he fired three shots at the thing, killing it.

Within a couple of weeks, Dyer says he uploaded video footage to YouTube, where it vaulted into the pantheon of furiously debated Bigfoot films. Andrew Clacy, a 47-year-old former television news cameraman and longtime Sasquatch enthusiast in Australia, was among the converted. He knew about Dyer’s history as a hoaxer, but he didn’t care. “Everyone overlooked it because we thought he had the real deal now,” Clacy says. “We thought it helped lead him to the real thing.”

When Meldrum got involved, the spectacle turned nasty. Two pro-Dyer amateur researchers visited Pocatello, Meldrum says, hoping to convince him of the body’s authenticity. It had already been autopsied, and DNA and tissue samples had been obtained, Meldrum recalls them saying. Plus, they had seen it. Were Meldrum to examine it, he would receive a $10,000 bank check; were the body to be proved a fake, he could cash it. When Meldrum declined, they upped the offer to $15,000. Meldrum says he laid out his terms: He’d need high-quality photographs posted on a secure website; he’d have to independently verify the credentials of the experts who examined it; and he’d need a no-contest stipulation for a fraud lawsuit in the event that the body was a fake. “I said, ‘This should be a no-brainer,’” Meldrum recalls.

There was no deal, and a video soon appeared on YouTube. In it, Dyer is wearing a cowboy hat and a striped short-sleeve button-up. In one hand, he’s holding a bottle of lighter fluid; in the other, he’s waving Meldrum’s book, Sasquatch: Legend Meets Science. “Dr. Jeffrey Douchebag Meldrum,” Dyer says to the camera. It’s dark, and Dyer is surrounded by a small audience. He looks like a drunk preacher as he reads aloud: “He knew his footprints were fake, but he thought in his mind, ‘Hey, there’s never going to be anything to compare it to.’ Until Rick Dyer. You’re busted, Mr. Douchebag.”

Dyer sprays the book with lighter fluid and drops it on the concrete. One of the men emerges and lights a match. Eventually, Dyer unzips his fly. “Roasted nuts,” someone says. The group laughs.

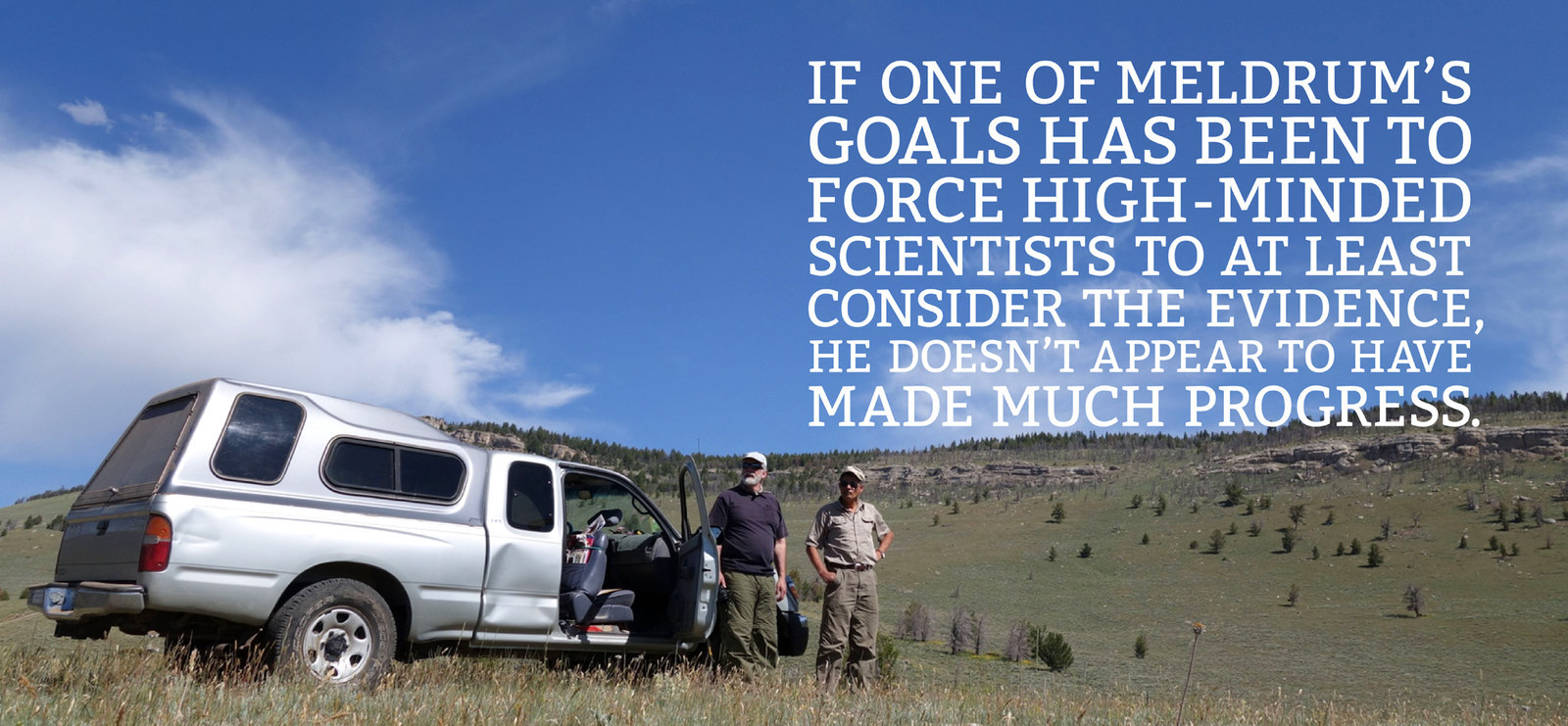

Meldrum has done his best to avoid a cage match with Dyer, to keep Bigfoot madness at the margins. But if one of Meldrum’s goals has been to rescue Sasquatch from the ditch of tabloid mania and force high-minded scientists to at least consider the evidence, he doesn’t appear to have made much progress.

There are a couple of exceptions. A decade ago in Bigfoot Exposed, Daegling examined Meldrum’s footprint work and concluded that he hadn’t considered plausible alternatives for the anatomical detail that he saw. With Patty, Daegling was noncommittal, saying that while the “dynamics” of her movement appeared real, it could have also been a very, very good costume.

Then, earlier this year, a molecular biologist from Oxford published the first-ever systematic DNA analysis of 30 hairs collected from around the world that were purported to have been collected from Sasquatch-like creatures. The results were not good for Bigfoot — they came back as horse, cow, raccoon, bear, even human — though the biologist, Bryan Sykes, seemed troubled by the lack of interest in the subject. “Science neither accepts nor rejects anything without examining the evidence,” he wrote.

I wanted to find out if Meldrum had convinced any of his colleagues to take Bigfoot seriously, so I assembled a brief anonymous survey and sent it to 10 anthropologists at 10 universities who specialize in primates. I asked if they were familiar with Meldrum’s work on Bigfoot and what they thought of it. I wondered if they thought Bigfoot could be a real species of primate and if it deserved to be considered by science. I heard back from three.

All of them knew of Meldrum and respected his non-Bigfoot research, but none were convinced that Sasquatch should even be examined; their argument, in essence, was that Bigfoot isn’t possible. “A mammal that large going undetected and undocumented in the Western United States for this long defies all probability and logic,” one said. When I asked what they thought it was, all three said a hoax. Or, as one put it, “a compound of hoaxing, confusion, hallucination, and folklore.” Meldrum is used to this. Once, when he tried to present Bigfoot-related research at a meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists, his submission was rejected. The program chairman later related the comments of one reviewer. “This is just not a subject that is of general interest to the anthropological community,” Meldrum recalls him saying.

In Meldrum’s view, the scientific reaction isn’t so much about evidence — though he did publish a scathing review of Bigfoot Exposed and he doesn’t have kind words for the molecular biologist. In his telling, it’s mostly a perception problem. Some academics have encountered little more than the tabloid mythology. Or the hoaxer. Others are overwhelmed by the intensity of the Bigfoot scene. “When a serious scientist shows some interest in the subject, they often become inundated with correspondence and contact requests from the amateur enthusiast community,” he says. “And there are some real strange people out there.”

In Rick Dyer’s telling, he believed that Morgan Matthews’ documentary, Shooting Bigfoot, would prove him a reformed hoaxer. He believed it would contain the high-quality version of that brightly lit, early morning encounter, and on his Facebook page, he began a countdown to last year’s Hot Docs film festival in Toronto, where the movie was to premiere. “I built it up like you wouldn’t believe,” he says. The film, however, contained just one brief scene from that night — Matthews chasing Dyer into the woods, then getting knocked over by something big and mean-looking. Its werewolf-like face and arm flash across the screen. Soon after, the movie ends.

Speculation cascaded: Was the shooting staged? Had Matthews participated in an elaborate hoax? Where was Dyer’s body? Matthews has remained cagey on the matter, telling the CBC, “There was something quite extreme” at the end of his film that “may or may not have been a close encounter.”

Dyer says the corpse was moved to a secure facility, and his investors were unwilling to release it. He was losing patience; he had a fanbase to satisfy, after all, and he wanted to capitalize on the attention. “I saw an opportunity,” he says. “I said, ‘Let’s make money off a fake one and let’s make money off a real one.'” Like the traveling sideshow exhibits that once enthralled 19th- and 20th-century audiences, he would tour the South, spinning fantastic Bigfoot tales. And he would show the evidence.

In the final weeks of 2013, Dyer assembled a small team that included Clacy, the Australian cameraman, and a few other fans. From a Spokane-based toymaker, he says he commissioned a $4,000 latex, Styrofoam, and camel-hair Bigfoot, which he called Hank and placed inside a plywood-and-Plexiglas box. It would be viewed in a trailer, which would be attached to a motor home. The whole enterprise, which Clacy says was underwritten by two investors and an $80,000 loan, would rumble down the highway wrapped in gaudy, impossible-to-miss advertisements that included a massive photograph of Dyer’s cowboy hat-clad head next to the comic book text of his pitch: “See the only dead Bigfoot.”

In Clacy’s telling, he had no idea Hank was fake. He packed up his home in Wodonga and flew to Las Vegas, where Dyer was living at the time, because he believed Hank was the creature shot dead in Texas. “We wanted to be part of history,” he says. (Dyer disputes this, saying Clacy knew that it was a hoax.)

Despite a dismal start in Phoenix in January, Texas proved lucrative. From Amarillo to Houston, San Antonio to Katy, Hank was presented in flea markets and a Home Depot parking lot, at Alamo Drafthouses, and, when passing drivers flagged them down, on the side of the road. Dyer says he usually charged between $5 and $10 a head, but for the roadside stops, he claims $100 wasn’t uncommon. About 10 people could fit in the trailer at a time, and the routine was fairly brief, Clacy says. He would tell the story of how Dyer killed Hank, and he would use the photographs on the wall as supporting evidence. “I think we had a 95% belief rate,” Clacy says, adding that even taxidermists and a medical doctor in Paris, Texas, seemed convinced.

The media was incredulous. In Las Vegas, before the tour even started, a reporter from Esquire wondered why anyone would believe an admitted hoaxer, while Meldrum was again asked to weigh in, this time by a reporter from the Christian Science Monitor. “The thing has clearly been fabricated,” Meldrum said. “It smacks of images of alien autopsy.”

Clacy says his suspicions grew, but they were tempered by the endorsements from the taxidermists and the doctor (who he now thinks may have been a fake too). Finally, in March, in Daytona, Florida, he says Dyer confessed. It was Bike Week, and they were in the parking lot of an event. “He said, ‘I needed you to believe,’” Clacy recalls. “I feel like an idiot,” he adds. “I believed a con man.”

In the days after, Dyer revealed the hoax in a long, blustery video message on Facebook because, he tells me, “I didn’t want no one else to bust it.” Half a year later, he still claims to have the body of the thing he killed with Morgan Matthews, and he’s still sanguine about his Southern tour. “It’s entertainment,” he says. “If you want to believe I would haul around a life-changing specimen in the back of a $10,000 trailer, then you go ahead and believe it.”

Afterward, Dyer sold Hank to a marijuana dispensary in Denver called Mr. Nice Guys. The owner, Jimmy Smith II, says he bought it for $5,000, and that he’s planning to build a terrarium for it. “I look at it as an investment,” he tells me.

When I met with Dyer in July, he told me he was planning a news conference for early next year to unveil the body of a Bigfoot — for real this time — and he was offering full-access viewings for $150,000. By September, though, he was promoting a new project, a Bigfoot hunt in Pennsylvania.

On a Sunday morning a couple of weeks ago, Dyer sent me a text saying that his “team” killed a Bigfoot the night before. He forwarded “exclusive” photos of something wrapped in a blue tarp, of his friends unloading ice bags from a shopping cart, of him in a camo hat and camo shirt attaching something to the roof of his black Toyota. Later, an image of what looked like intestines arrived on my phone. “That’s the inside of the Bigfoot,” he said. The creature, Dyer told me, was found outside Hazelton, and like most Eastern Bigfoot, at least as described by Loren Coleman, it was small: 5-foot-7 and a few hundred pounds. “I got this one in my possession and it can be proven,” he wrote.

When I tell Meldrum about some of Dyer’s plans, he chuckles and offers the "Fool me once, fool me twice" line.

“What about a third time?” I ask.

He laughs. “Double shame on me,” he says.

A previous version of this story referred to the Patterson-Gimlin footage as having been in black-and-white.