There is a moment in the very first scene of the very first episode of Scandal, in which Harrison Wright (Columbus Short) says to Quinn Perkins (Katie Lowes), “Olivia Pope is as amazing as they say.” Quinn was already in the tank; moments earlier, he informed her that he was offering her a job at Olivia Pope & Associates (OPA) and an eyes-wide Quinn accepts the offer, drooling, and without asking for any details. The scene signals to the audience, before Olivia Pope even appears on screen, that it’s about to be introduced to a legendary character, not just because she didn’t look like the any of lead characters on network TV at that time, but because she wasn’t like any of them either.

Looking at the TV landscape now, it’s easy to forget that in 2012 Kerry Washington became the first black woman to lead a network drama in 40 years. (The first was Teresa Graves in 1974 as an undercover cop in Get Christie Love!) Scandal’s creator, Shonda Rhimes, and Washington made history with the origination of Olivia Pope, Washington, DC’s best fixer with crisis-ridden clients ranging from executives to the fictionalized president of the United States. The character was loosely modeled after real-life crisis manager Judy A. Smith, who is black and worked in the George H.W. Bush administration. Seven seasons later, Washington is joined by Viola Davis and Taraji P. Henson, and they, along with the many black leads who have teamed up with other networks and cable channels, have transformed television. In fact, there have been more black women leads on network TV in the six years since Scandal’s debut than ever in history, suggesting that increasing blackness on television may be OPA’s greatest “fix” of all.

“I didn't know from the beginning that I wanted Olivia Pope to be a black woman, I knew from the beginning that Olivia Pope was a black woman."

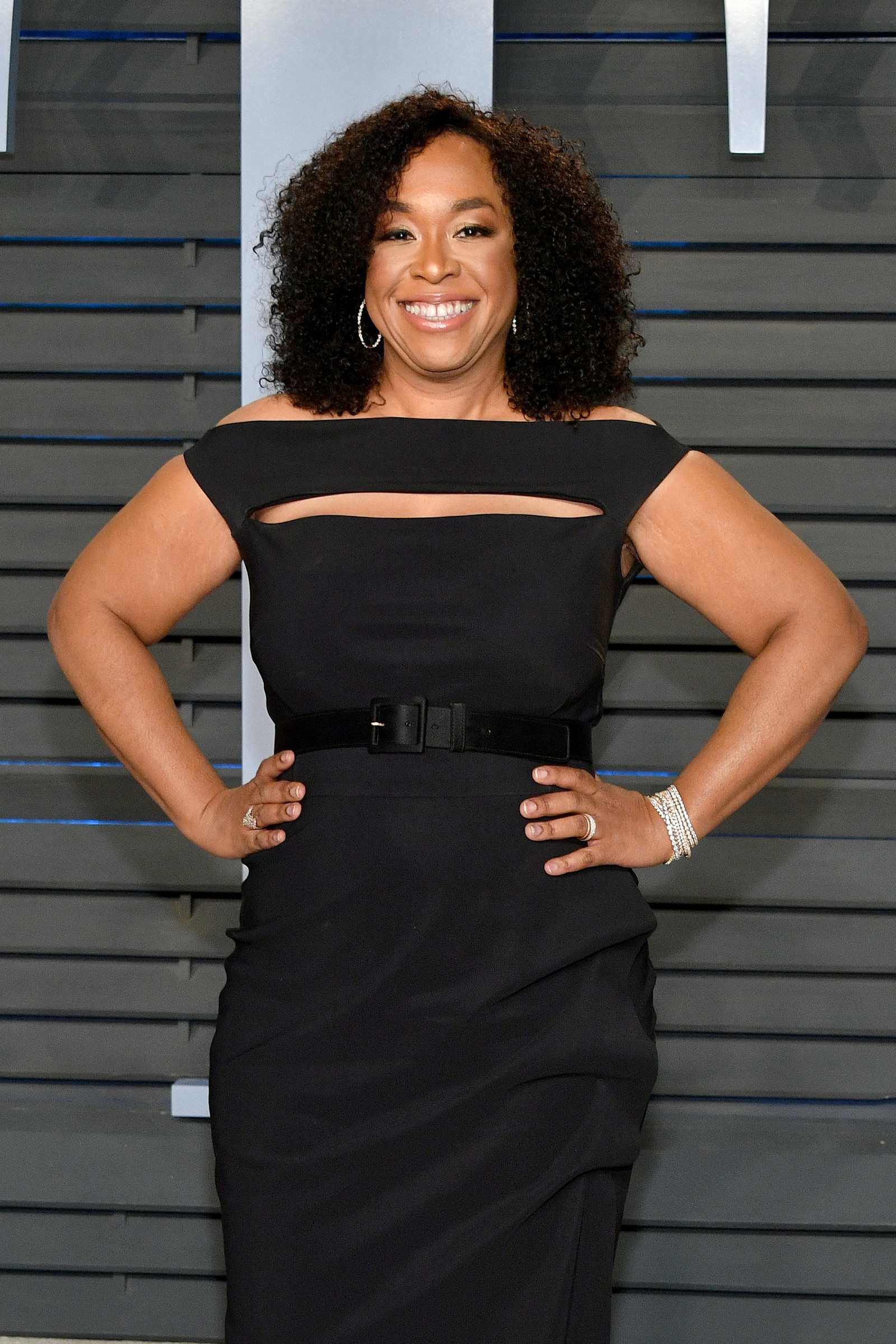

Rhimes — who had launched the hit long-running medical drama Grey’s Anatomy years earlier — couldn’t see Olivia Pope any other way. “I didn't know from the beginning that I wanted Olivia Pope to be a black woman, I knew from the beginning that Olivia Pope was a black woman,” Rhimes told BuzzFeed News. “It wasn't a discussion and it wasn't a ‘I hope someone is going to let me.’ It’s what I imagined in my head, so that was what needed to be happening onscreen.”

It’s the kind of powerful statement that demonstrates why Rhimes was the perfect architect for such a monumental character. Not only is Rhimes a black woman herself, but she is also one of the few players in the industry who could make a network as big as ABC take that kind of leap. At the time of Scandal’s release, the network’s top dramas were Desperate Housewives, Once Upon a Time, Brothers & Sisters, Revenge, and Grey’s Anatomy. The latter was Rhimes’ first contribution to the network, and one of the only dramas with a large group of actors of color — a “concept” Rhimes’ production company doubled down on in her second medical drama, Private Practice. Both of Rhimes’ dramas were evidence that diverse representation on television could be successful, although Rhimes, who doesn’t like the word “diversity,” prefers to think of her efforts as showcasing what the real world looks like. Still, both Grey’s Anatomy and Private Practice had white women as leads. Giving the top billing to a black woman in Olivia Pope was the next big step.

“Shonda is so smart — it really can’t be overstated what her impact is,” said Dear White People creator Justin Simien, one of the many black TV show creators who enthusiastically credit Rhimes, in part, for their own success. “She created these little Trojan horses, where you’re like, ‘Am I watching a black show?’ It’s like she pulled a magic trick, Trojan-horsing black folks into the popular culture for years.”

Actor Aja Naomi King is also a clear beneficiary of Scandal’s success. As Michaela Pratt on ABC’s How to Get Away With Murder, Shondaland’s second drama to have a black woman (Viola Davis) star as its lead, King has become part of the growing list of black women Rhimes’ company has been able to create prominent roles for. The actor spoke to BuzzFeed News about what it was like to watch TV’s first black woman-led drama in decades come together. “When Scandal started being advertised and stuff and it was just Kerry Washington's face everywhere, it was like, Is this really happening? Are we really about to have this primetime show with this female black lead in an hourlong drama? There are serious stakes here,” she remembers thinking.

And Rhimes and Scandal were treated like a huge gamble by ABC, which ordered an only seven-episode first season that ran over spring 2012. Rhimes is candid about why she thinks ABC didn’t put its full trust behind the show, despite her track record with Grey’s. “As somebody who had made a gigantic hit for a network, a hit that 14 seasons later, it is still a hit, to be given only seven episodes of a show that I made was a problem,” Rhimes said. “To me it spoke to a lack of faith in the idea that a black woman could be the lead of a television show. And I found that to be insulting.”

"As somebody who had made a gigantic hit for a network, a hit that 14 seasons later, it is still a hit, to be given only seven episodes of a show that I made was a problem."

To loosely quote Rowan “Eli” Pope’s (Joe Morton) most classic Scandal monologue and an adage among black Americans, the black-led show was going to have to be twice as good to get half of what the white-led shows had. But, like the Popes themselves, Scandal proved itself to be a formidable competitor. One key way the cast and crew did this was live-tweeting with fans while the show aired.

“The Season 1 ratings weren’t great and Kerry had the idea for us to start engaging with fans more on Twitter,” Morton told BuzzFeed News. “It was great for us to see the live reactions from fans — it’s kind of like the closest thing you can get to the Broadway experience on TV.” Like most of the cast, Morton has spent a significant portion of his career on stage. At the time, Twitter users, especially Black Twitter, were largely live-tweeting live TV events like award shows or sports games. It wasn’t necessarily routine for the community to meet weekly at the same time to experience a network show together, with the stars of the shows, via social media.

“It fell into the culture that was already there and blew it up,” said Luvvie Ajayi, who became one of the series’ most recognized bloggers. “It turned Thursday night into the night you wanted to make sure you were on Twitter as part of this community for this new show that was gripping everybody.”

By the second season, it felt like everyone on Twitter was watching Scandal, and the ratings boost the drama received as a result of the Twitter campaign showed Washington’s plan had worked. According to a Nielsen report in 2013, Scandal became the highest-rated scripted drama among African Americans, with 10.1% of black households, or an average of 1.8 million viewers, tuning in during the first half of the second season. The Season 3 premiere came alongside record-breaking numbers and continued to pull in about 10 million viewers regularly. The show was a hit, and a large chunk of that success was due to the two black women running the show, both on- and offscreen.

When Washington makes her first appearance as Olivia Pope, she’s donning a chic white trench coat that tells us she’s braver than most, a pair of heels that show she’s about her business and fashion, a power strut that rivals Barack Obama’s, a roller set bouncy enough to assume she goes to the salon weekly, and a tongue quick enough to out-negotiate the best of the best. She was gorgeous, brilliant, powerful, and...black.

Every week we watched Olivia Pope fix seemingly unsolvable puzzles, battle political villains, and save lives without superpowers or a weapon; she was enough. It was both thrilling and inspiring for black women to see ourselves depicted by someone everyone on the show respected as a supreme leader. More important, she was also raised to believe she was the best. She was afforded an amazing boarding school education and had a very “Jack and Jill” childhood, with exposure to the best culture money could buy. Her father was (secretly) the most powerful man in DC, her mother was an assassin, and she was a neglected only child — they were unlike any black family we had ever seen.

It’s also worth noting that Washington was a lead in every sense of the word. She didn’t just have top billing in the credits; everyone looked to her for leadership both behind and in front of the camera. “To me that was so key,” recalled King. “It's not like she was standing around and everyone else was doing the talking. No, she's commanding the room, she's navigating what the issue is and how it's going to be solved, and everyone is deferring to her.”

It would have been easy (and boring) for Rhimes to make a character with Olivia’s pedigree perfect, but she decided to challenge the notion that black female characters had to be likable or inherently good in order to be great. As the series went on, we saw Liv’s wrongdoings progress from having an on-again, off-again affair with a married president, to fixing an election, murder, and treason. By the time Season 7 rolled around, Olivia had gone dark and become a full-on anti-hero. Hell, some might say she became a flat-out villain. It was a progression we’d watched happen to white men and occasionally white women on dramas like Breaking Bad and Mad Men, but never had a black female character been given the time and space to progress in this way in front of millions of viewers on network TV.

The range Rhimes provided Olivia floored King — it flew past all the usual black women character stereotypes. She wasn’t the super nice and/or funny type, she wasn’t necessarily a good friend, she wasn’t desperate for a family, and she certainly wasn’t a self-sacrificing mammy solely there to take care of someone else — though she was occasionally accused of this by her father, which was another dimension of their complicated relationship. “She was a professional being relied upon as the intelligent person in the room who is going to be able to solve the conflict. She was the leader, the boss, which was so rarely seen,” said King. “That wasn't a thing that existed. We were given amazing bits of it on another amazing Shonda show, Grey’s Anatomy, with Chandra Wilson as Miranda Bailey, but she wasn't the lead of that show.”

Rhimes knew the importance of making sure Olivia didn’t fall into the usual black girl tropes. She had to break through that glass ceiling to be as extraordinarily complicated as the leads of other network dramas. It was vital for people to see a woman of color do that successfully on TV if there was to be real change. “In order for Olivia Pope to work and to succeed, and to make sure there could be a second black lead in another show, she had to get to be as three-dimensional and as messed up and bad or good or smart or interesting as the Walter Whites of the world got to be,” Rhimes explained. “Frankly, that's the thing that's true for a character of color but also for a woman. There aren't very many women who get to be those things either on television.”

Although Rhimes was making history by creating such a complex and undeniably dark character, it was hard for some to see a black woman in such a big role, portraying such a flawed character. Perhaps the most criticized of her faults was her role as the president’s "mistress." Viewers often shared that they were put off by the relationship for multiple reasons, and black women especially were sensitive to the racial optics: a white man being this otherwise strong black woman’s kryptonite, the one who made her lose her control, the one who added the first big stain on her pristine reputation when it was revealed that she was his lover. However, the show did manage to add layers and depth to Olivia and Fitz’s relationship throughout the series and portray a more nuanced affair. The love between the characters was real — they may even be each other’s soulmates — and it got slightly less controversial when Fitz finally got divorced. But their sheer inability to let each other go no matter how many times they claimed it was “the end” was often maddening to watch.

But as King said, those moments are often frustrating because they’re representative of internal conflicts we have experienced in real life. We hate to see a character we’ve connected with make those same mistakes. That’s part of the purpose of art, to make its intended audience feel. But black women especially were sensitive, and maybe even protective, about Olivia because for some time she was the only version of ourselves we got to see on network TV. King also noted that the frustration came because we weren’t used to seeing a black woman unapologetically make completely selfish decisions that hurt people. “So to see a black female character as someone who is a little messed up, doesn't have it all right, dealing with their own demons — that is what it is to be fully human and be a fully realized character. Because no one is perfect, no one is fully self-sacrificing. You wouldn't be able to survive,” she said.

Rhimes held steadfast to many of Olivia’s heavily critiqued flaws, though she knows why they struck a bad chord with black audiences: “You know when there's only one of something, everyone's rooting for that person and we all have that sort of collective holding of our breath of, you know, 'Don't mess it up,’ so that there could be a number two. That's really a feeling that we all have,” Rhimes said. She added this caveat: “But the idea that we should put a black woman as the lead of a show and keep her perfect, to me would have made a very unsuccessful show. While the instinct is there for her to have a role model quality, I think we all carry around in us a feeling of responsibility that could not apply to Olivia Pope.”

"To see a black female character as someone who is a little messed up, doesn't have it all right, dealing with their own demons — that is what it is to be fully human and be a fully realized character."

Relieving Olivia of (some of) the respectability politics is something that stood out to other show creators. Simien says it even allowed white audiences to relate more to the black character, something that was vital for it to transcend having one type of core audience. “The character she created for Kerry is so complicated and flawed and so brilliantly rendered. I feel like white people can see themselves as black people a little more on TV shows. We’re sort of being seen as complicated and human. We have struggles. We’re just like everybody else. It’s beautiful [to see on TV],” he said.

Simien added that Rhimes’ mindset opened the door for a wave of beautifully flawed black women leads on television. Suddenly, they were more visible. There was Mary Jane Paul (Gabrielle Union), the lead character on BET’s Being Mary Jane, who, like Olivia, started the series as both a career woman and having an affair with a married man. There was also Cookie Lyon (Henson) from Fox’s Empire, a ride-or-die mom and lover with a killer attitude and ear for music. And, of course, Annalise Keating (Davis), the aforementioned second black female anti-hero created by Rhimes for ABC’s HTGAWM, a troubled and successful law professor with an alcohol problem and a knack for being involved in murder plots.

This wave of black women landing major leading roles in dramas shared another commonality: They were all the top black actors in film, and suddenly they were making a mad dash to the small screen where more fruitful, complicated roles were beginning to flourish. There was Halle Berry’s on CBS’s sci-fi drama Extant, Jada Pinkett-Smith on Fox’s Gotham, and Angela Bassett on FX’s American Horror Story and now Fox’s 9-1-1. And this particular trend wasn’t limited to major female black film stars: Morris Chestnut (Rosewood), Wesley Snipes (The Player), Terrence Howard (Empire), and Anthony Anderson (Black-ish) also made the jump to television during Scandal’s era. It’s true that actors of all races have historically jumped between the big and small screens, but the sheer volume and stature of black actors doing so in such a short span of time — most of these shows were created by 2015, three years after Scandal — is notable. And while it can’t be said for certain that Scandal is the sole cause of these shows’ existence, the success of the show likely influenced networks to give these other shows and actors a chance.

King recalls seeing the difference in the number of TV auditions that opened up for her as a black actor after Scandal aired. “When you look at a script or breakdown for a character, if they didn't include her race, the assumption was that character was meant to be white. It wasn't until [Scandal] came out that it really broadened the idea, the concept of what race you needed to be to be a lead on a show and what that meant,” King said. She went on to note that the change was a slow but steady one: One day she looked up and realized that the audition rooms she was going to were more varied and less predominately white.

One of the reasons King found herself in more rooms with white women — instead of just more exclusively black rooms opening up — is because a lane had been expanded for black actors to fill roles that weren’t specifically written for black actors. Like Olivia, the characters they were playing were not defined by their race or necessarily written to be black — they were just cast that way. Rhimes says it’s one of the things she loves most about this new era of black TV characters, in addition to not just seeing a few rotating versions of blackness. “In the Scandal writers room we call it the ‘my black is not your black’ conversation,” she said.

An example of this from the series, according to Rhimes, is the dynamic between Olivia and her father. The creator described Olivia as a post-racial, post-Obama kind of black woman who believed in the idea that the United States was finally all equal and perfect, that the world was truly her oyster. In contrast, Rhimes characterizes Rowan as a militant kind of black man, one who was very aware that some things don’t just change and that you have to learn to work the system before it inevitably works you. This dynamic played out throughout the years a lot in their arguments, which produced dialogues about blackness we hadn’t ever seen on network TV.

“It’s always so funny how quickly we forget the trailblazers, and I think that now that we have Taraji and Viola and all these wonderful people that are getting to lead shows, we’re forgetting that Shonda created an opportunity for Kerry first,” said Yvette Nicole Brown, who most recently starred on ABC’s The Mayor, another black-led network show that came after Scandal. “So I bow down to them for that. I bow down to ABC for knowing that it’s possible, I bow down for everyone that’s come since and kicked the door in and killed it. It is a great time to be black and female in America. It really is.”

It wasn’t just black actors who were benefiting from this Scandal-sparked boom. Black writers and producers were also given opportunities to shine on networks that had long ignored their value. It was almost as if every major TV channel was looking for its own versions of Shonda Rhimes. The partnership that got the closest to this was Fox and Lee Daniels. His show Empire is the only network drama that, at its height, rivaled the popularity of Scandal. The musical drama premiered to an audience of 13.1 million and its ratings climbed 39% in its first month. That’s more than any other broadcast drama since House in 2004. The show was so successful that Fox gave Daniels the opportunity to create another series for the network: Star premiered in 2016, only a year and a half after Empire. In true Shondaland fashion, the dramas aired back to back on Wednesday nights and continue to do so today.

“I feel like every single one of us has taken a cue out of the Shonda Rhimes playbook,” said Empire star Jussie Smollett. “I know for a fact there would be no Empire, there would be no Queen Sugar, there would be no Greenleaf… none of all these incredible opportunities and art that’s being created.”

Queen Sugar, Ava DuVernay’s emotionally complex black family drama, is another example of Rhimes’ impact behind the screen, as is the Oprah Winfrey–produced Baptist church drama Greenleaf. Kenya Barris also found sitcom success at ABC with Black-ish and Freeform with its spin-off Grown-ish, reviving the popularity of the black family sitcom that had seemed to die in the ‘90s. There was also NBC’s The Carmichael Show, which lasted three seasons before its black creator and star Jerrod Carmichael pulled out after issues with the network. Issa Rae followed Carmichael’s recipe by starring in Insecure, the HBO comedy series she created for black millennials, after having developed a show with Rhimes that didn’t get picked up. Donald Glover did the same with FX’s Atlanta, the acclaimed and popular series he created with his brother, Stephen Glover. There’s also, of course, Simien’s Dear White People drama on Netflix and the newest of these offerings, Lena Waithe’s drama, The Chi, on Showtime.

“At the end of the day, the only thing people care about is commerce in this town,” Waithe said. “And Scandal really made people wake up and pay attention, because it was making money. People were watching it in droves, and it just changed the game and made it easier for people to get a show about a black woman or a black person on TV. I’m grateful to Shonda for opening those doors and just being that trailblazer so that other people could walk through.”

It is clear that many of the aforementioned troupe of creators are a part of Rhimes’ legacy, some directly as mentees like Rae and author Ajayi — who is currently developing a comedy with Rhimes based off her book I’m Judging You — and others simply because she made TV great again by reminding networks that diversity makes money when it’s done right. And even more so when it exists both in front of and behind the camera. In fact, the black-led shows that have garnered the most popularity and longevity are the ones that also had black creators and/or multiple black writers in the room: Atlanta, Insecure, Empire, and Black-ish were all created by a black producer. On the other hand, most of the short-lived ones, like The Mayor, Extant, Deception, and Rosewood, were not.

But as the landmark show that started this new era of black diversity on television comes to an end Thursday, the elephant in the room is this question: Will the progress it has made on television leave with it? Or has the trend finally permeated through media deep enough to become the mainstay it deserves to be?

While contemplating this, Rhimes notes the period in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s when The Cosby Show was the No. 1 show on TV, Eddie Murphy was a box office king, Whoopi Goldberg was on Broadway, and basically everyone thought that things had finally changed for good. “And then suddenly everything became very white again,” Rhimes said. “What I like [this time around] is that the economics are very clear that people want to see people who look like them and that the demographics are very clear about what America looks like. I'd like to hold on to the idea that we’re running forward. ... I hope this is the beginning of something amazing.” ●