Evita Wallenda is perched on a concrete highway divider, finger-drumming on a hole that's been covered for some reason by duct tape. "I'm reeeeeally bored right now," she sighs theatrically as only a 12-year-old can. About 120 feet directly over her head, her father is steadily walking his way across 1,576 feet of high wire stretched out above the Milwaukee Mile speedway, the evening's main attraction at the Wisconsin State Fair. Her two older brothers, Yanni, 17, and Amadaos, 14, are among the 22 crew members, all relatives or longtime friends, scurrying and checking the support ropes for tension as Wallenda progresses. This is billed as the longest walk of Nik Wallenda's career, 30 or so feet longer than when he crossed the Grand Canyon in 2013; he needs to push the envelope but he also needs to pace himself to support a life of subsequent record setting. But it's nothing Evita Wallenda hasn't seen before, every day, her entire life.

Watching a man walk slowly in a straight line does not seem like usual speedway fare, but from directly below the wire, each step is heart-stopping. Wallenda's feet, sheathed in special leather slippers handmade by his mother, Delilah, curl around the steel cable just so, but the margin for error is acutely, viscerally measurable. The grandstands are not full, maybe a couple hundred people, but the wire is visible from much of the sprawling fairgrounds, a slowly moving dot that is as much a part of the landscape as the Ferris wheel and villages of cheese curd stands. From that distance, what he does is so abstract — there's no mystery as to what can go wrong, of course, but from this vantage point directly below, it's so much clearer just how easily that could happen.

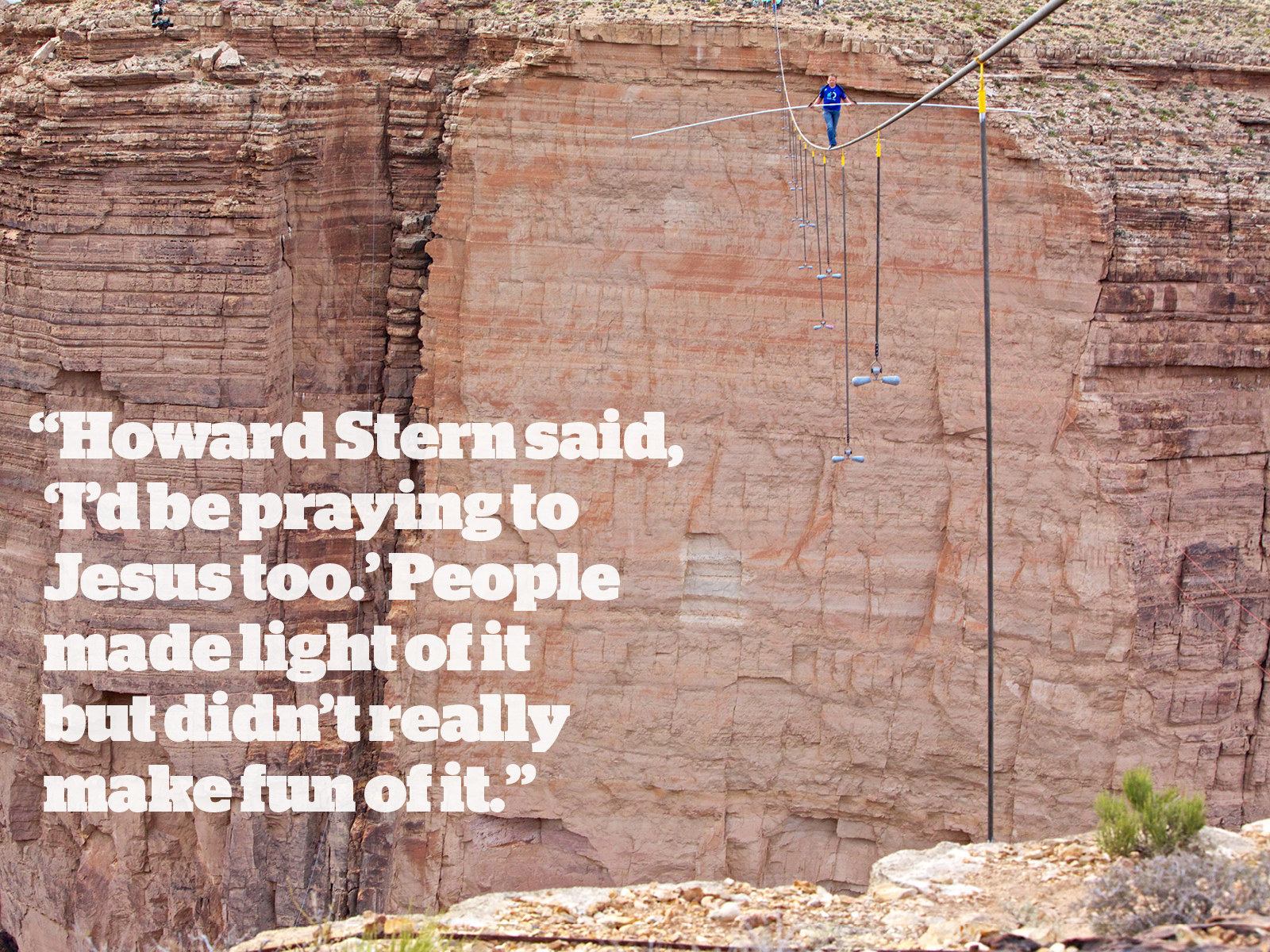

The cable is three-quarters of an inch in diameter and lined with 118 support ropes, 59 on either side. Each rope is held tight by a volunteer; a local radio station promised 120 contest winners to hold the guy wires, but fell a few dozen short. A few were too drunk to perform their duties as human ballasts — it's the end of a long, hot August day at the fair — so the difference is made up with state fair employees, spare crew members, and a lurking journalist. This isn't a new problem or one that hadn't been anticipated — for a walk a few years ago, so many volunteers were too drunk to hold the ropes that Wallenda had to more or less go unsupported. When Wallenda walked over the Grand Canyon and Niagara Falls live on television, a much thicker cable was used because there was no way to stabilize with ropes and humans. Wallenda feels every vibration, every variation in tension; the less of either, the better.

At 6 p.m., about an hour before the walk was scheduled to begin, Wallenda stood in the loading area behind the fair's main stage clutching a megaphone, flanked by two of the riggers, and demonstrated how everyone needed to stand inside the rope's loop, placed just below the butt, and lean back so the line is as taut as possible. Oh, and, crucially, no mid-walk selfies by the rope holders, which was a big problem the time a high school football team served as holders — he notices every slight shifting of weight up there, please just be still, at least until Wallenda is several ropes past. "It's not that important a job," Wallenda announced through the bullhorn cheerily, "but if you screw it up, I'll die."

Wallenda's guest of honor at the walk is Coulter, an 8-year-old fan from Houston with brain cancer, who is here with his mom and grandfather. They were part of the pre-walk prayer circle with his family and crew, and Wallenda introduces him from atop the wire, a brave kid going through a rough time. Wallenda and Coulter are both wearing a black wicking T-shirt with an NW/Nik Wallenda logo on the front and "Never Give Up, Coulter!" on the back, along with Isaiah 53:5 ("But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities: the chastisement of our peace was upon him; and with his stripes we are healed"). #NeverGiveUp is Wallenda's motto and how he signs off on his social media dispatches — big-top attraction as motivational guru.

He speaks over the PA the entire duration of the walk, interviewed by the emcee who is standing on the grandstand stage, rattling off lines he says practically every time he is near a live microphone: that he's a seventh-generation performer, that his great-grandfather Karl Wallenda used to say, "Life is on the wire, everything else is just waiting." He's so dialed in the words may be coming out unconsciously. He later plugs his soon-to-air episode of Say Yes to the Dress featuring him and his wife, Erendira, renewing their vows; they never had money to throw themselves a real wedding 15 years ago, he explains casually. He has to pause and kneel on the wire several times, his monitor and headset mic keep slipping off his ear — of all the things that could kill him right now, indulging in light banter has shot to the top of the list. Three-quarters of the way across, crew members scramble to stabilize a spot in the wire that isn't taut enough. Then Wallenda reaches the end of the line and is lowered down on a lift, where his family and Coulter's family greet him, another record on his CV.

The best circus performers were always as good at branding as they were at swinging from trapezes and standing down lions — they just didn't call it that. Wallenda is more than happy to call it that; his dozens of cousins and uncles and stepcousins, he thinks they'll never get it, they don't want it bad enough, they would rather tear him down than build themselves up. Self-promotion is no less an integral survival skill than keeping one's balance on a wobbly steel wire no wider than a nickel, and no less susceptible to volatile environmental vagaries. He is known for crossing Niagara Falls and the Grand Canyon while unabashedly praising Jesus during live, widely viewed primetime TV specials, but he is not known as well as he would like. For all the cinematic audacity of the event walks he's plotting for the future — between the world's tallest twin towers in Kuala Lumpur, over rain forests in Brazil, atop skyscrapers in Times Square — openly coveting household-name ubiquity for performing potentially suicidal acts in front of the largest audiences possible at a time when spectacle is cheap and readily accessible in your pocket, all while maintaining an image as a pious, God-fearing family man is, in fact, Nik Wallenda's most daunting challenge. He knows he's not going to fall off a high wire.

"I’ve had people come up to me and touch me to see if I’m real," Wallenda, 36, says over lunch at a Longhorn Steakhouse near his home in Sarasota, Florida, one afternoon in June. "People are fascinated by the fact that I could die at any point. They don’t necessarily want me to die, although there’s probably a certain percentage that do, and that’s OK. It doesn’t offend me whatsoever; that’s the reality of what I do. I know that’s gross and scary, but it’s the truth." Next to him is his intern, John, 18, a recent graduate of Sarasota's vaunted Sailor Circus, a training school for performers that is part of the town's heritage as the longtime American capital for all things circus-related. (When Wallenda drops in during a summer camp session, he is besieged by young autograph seekers.) John is apprenticing to learn the trade, both on the high wire and off.

Wallenda's hair is blonde thinning and swept back and to the side, his boyish face freckled and tattooed a reddish bronze from a life spent under the Florida sun learning how to not fall off of things. He wears, as he almost always wears, a tight T-shirt with a long crucifix necklace over it. He sips an iced tea and gingerly flexes his swollen hand, injured in a home-repair mishap as his new house was being remodeled. Amadaos recently broke his right hand trying to punch through drywall, only to find a stud. "Accidents come in threes," Wallenda sighs.

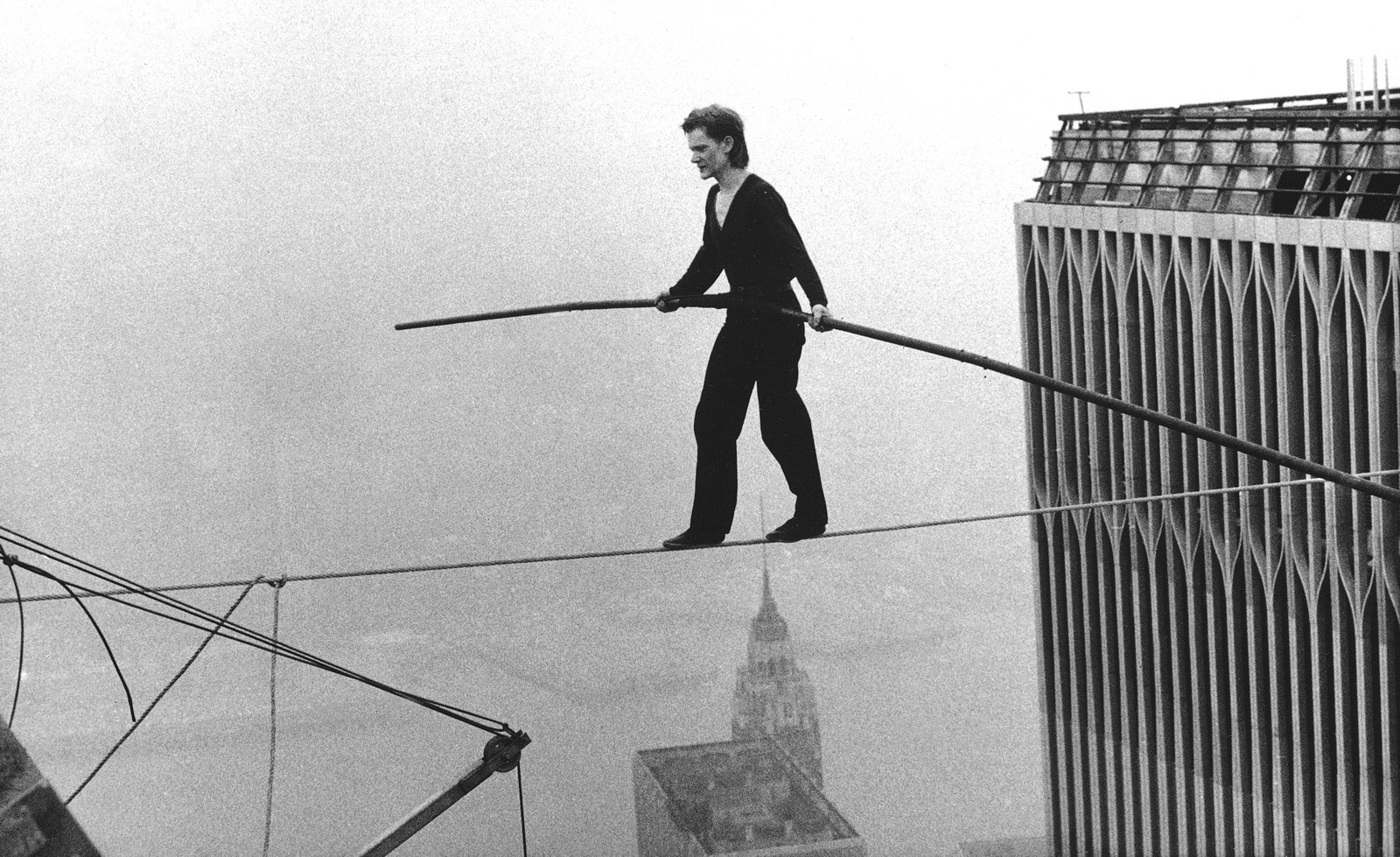

After a couple hundred years as cultural sideshow, funambulism is having an unlikely moment thanks to The Walk, Robert Zemeckis's vertigo-inducing dramatization of Philippe Petit's 1974 renegade tightrope walk between the newly erected Twin Towers, previously chronicled in the Oscar-winning 2008 documentary Man on Wire. If Joseph Gordon-Levitt's portrayal of Petit is the face of this art form as expressionistic, authority-flouting public spectacle, then Wallenda is its pragmatic flip side — careful, law-abiding, part of a long-tail business plan.

Nik Wallenda was born Nikolas Troffer, a fluke of societal patronymic bias. But he is a Wallenda by blood and by trade, the standard-bearer of the most hallowed bloodline in circus performer history, the most visible branch on a family tree that looks like kudzu and contains enough shifting alliances and betrayals and clan rivalries to exhaust George R.R. Martin. Wallenda estimates there are as many as 14 of his relatives currently performing around the world. He doesn't speak to many of them.

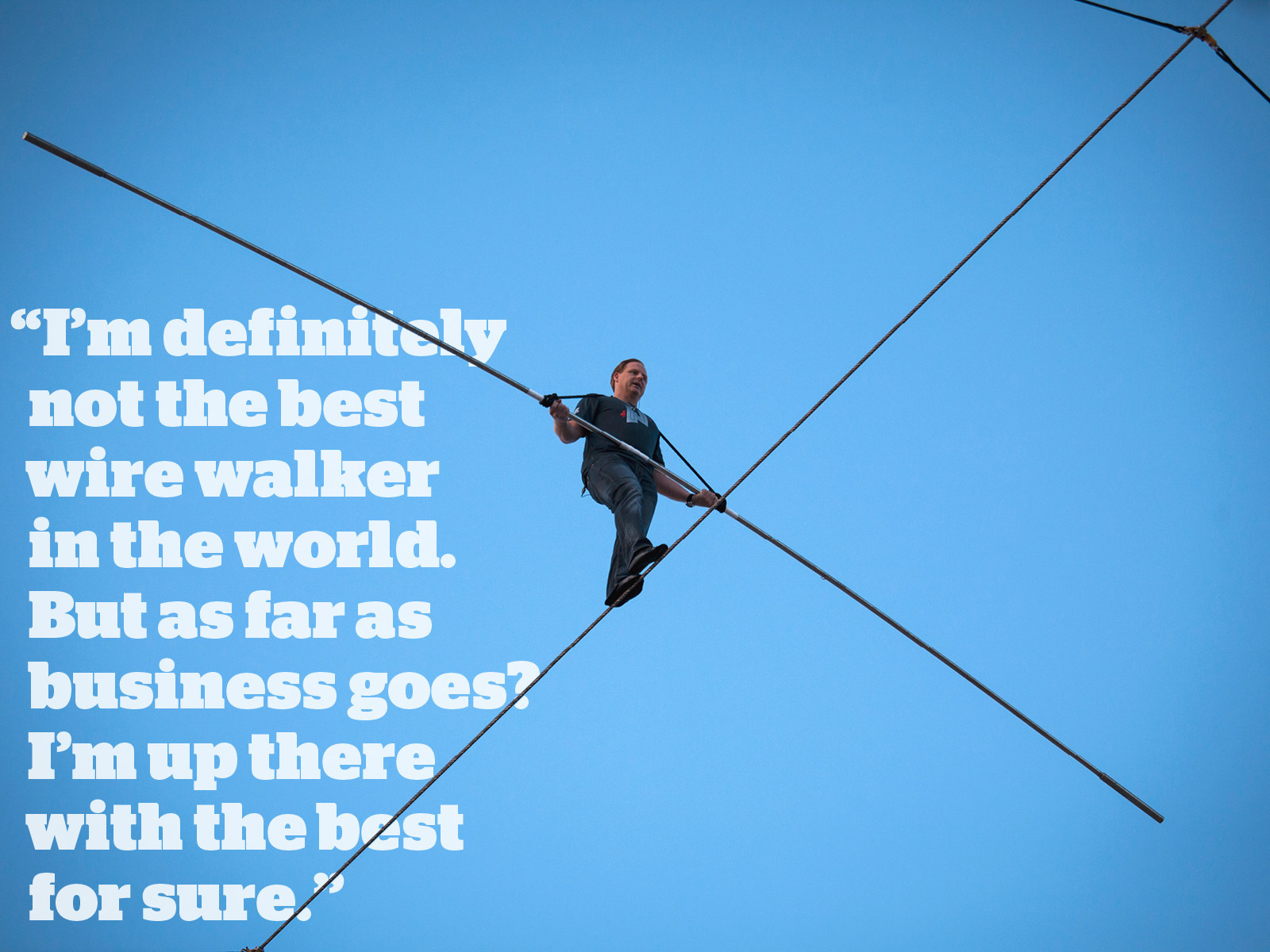

"When I broke my first record by myself in 2008, for a lot of the headlines, I think it was the New York Times, it was 'King of the High Wire,'" he says. "So my managers read this and said, 'We’re going with this, that’s a great title. My family hates that: How dare you call yourself King of the High Wire? It’s a marketing tool! You can put it on the record: I’m definitely not the best wire walker in the world. But as far as business goes? I’m up there with the best for sure."

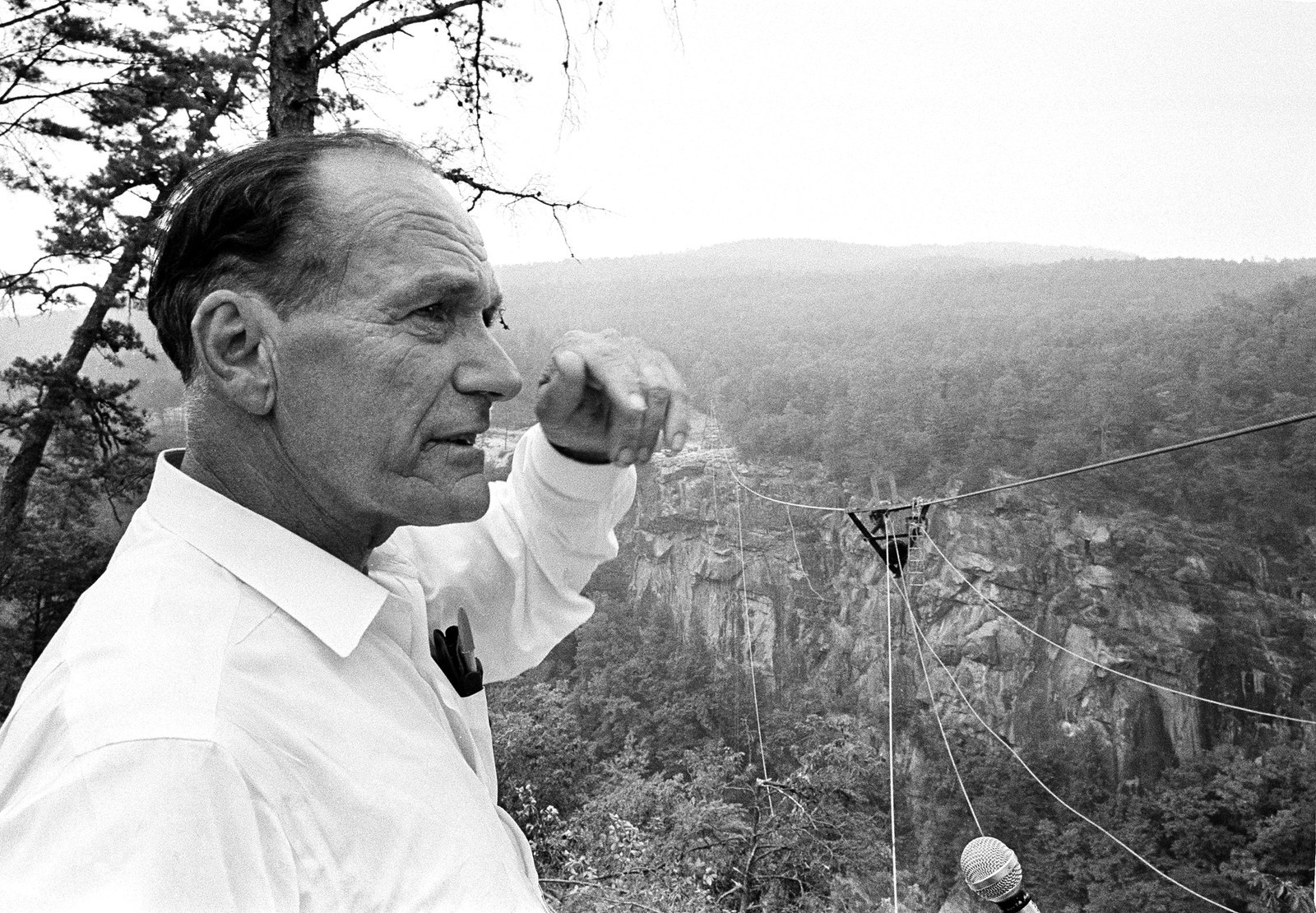

Karl Wallenda was the German-born patriarch of The Flying Wallendas, a name coined in the ’40s that he loathed — and not just because it led people to mistake the family for trapeze artists, but because wire walkers don't fly unless they're falling. (The name, in fact, was first used after an accident in Ohio.) Nik Wallenda was born in 1979, the year after Karl Wallenda fell to his death during a walk in San Juan, Puerto Rico. To say that his great-grandfather informs every aspect of his life is underestimating the degree to which family is the dominant force in circus performing, as well as the degree to which Karl Wallenda has defined, and still defines, that tradition. Much of the division among factions is complicated and deep-seated, and most certainly about money, but it comes down to who is most worthy of Karl's legacy, and his valuable surname (which itself has been the subject of numerous legal battles).

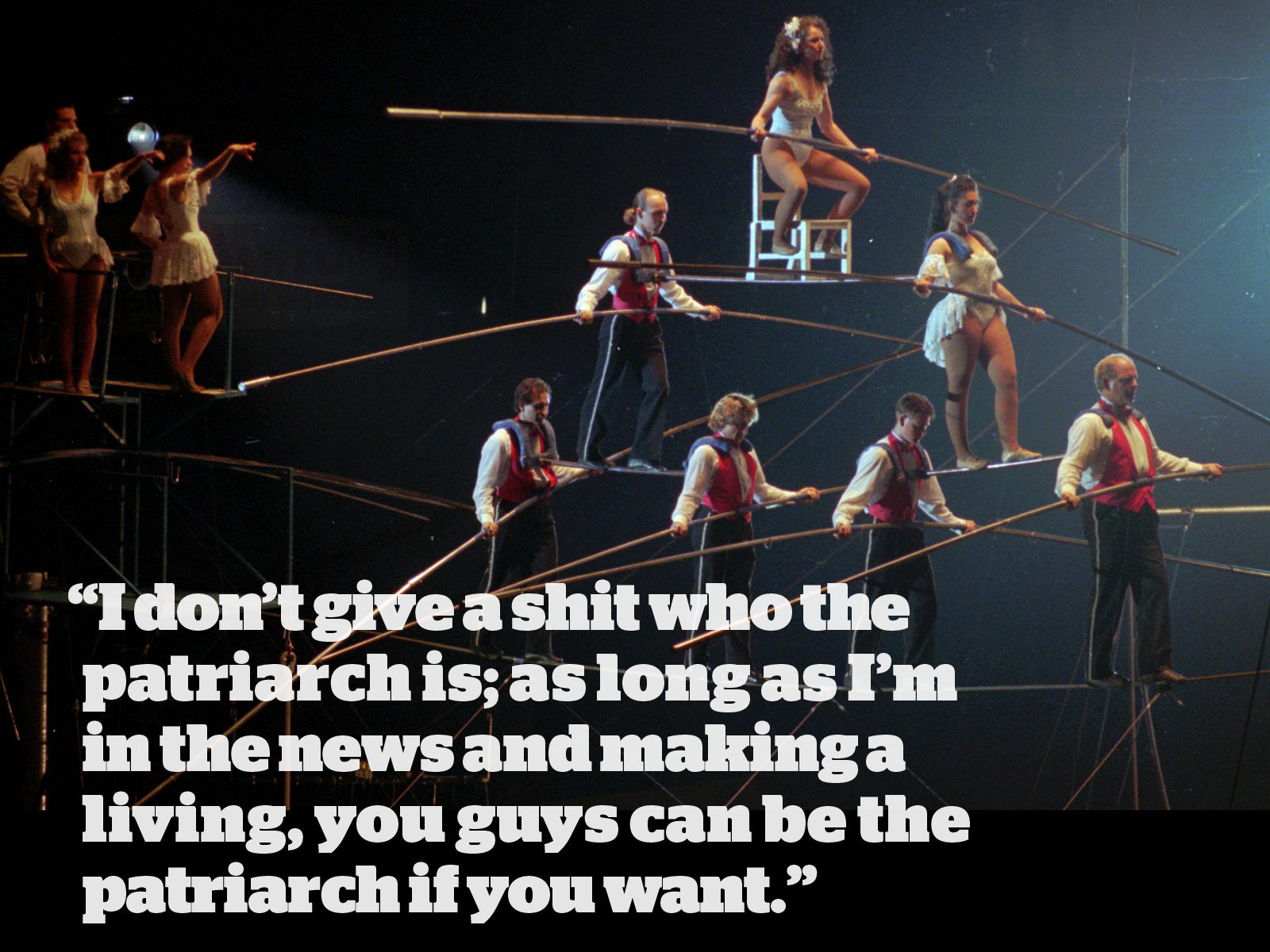

"There’s these groups with no leader, so now there’s competition, everyone feels threatened, there's this fight for who’s the patriarch," Wallenda says. "It’s the same lineage, same generations, the same great-grandfather, there’s always been this battle. I say this all the time, but I don’t give a shit who the patriarch is; as long as I’m in the news and making a living, you guys can be the patriarch if you want."

Delilah Wallenda, 62, is the daughter of Jenny, who was the daughter of Karl and Martha, a ballerina he met when she was 15, married, then soon left. She married Terry Troffer, 60, in 1975. Troffer, who along with his brother Mike oversees the rigging on his son's walks, did not hail from a circus family. He joined the Sailor Circus and became an engineer; you can't be a good wire walker without being a good physicist. Delilah and Troffer performed as the Delilah Wallenda Duo for years. In 1980, Delilah says, they were performing 48 weeks a year, but that started fading around 1986, and what was once a nice living became increasingly untenable. "The people who ran the circuses started gearing them to children," she tells me one afternoon in her backyard, where she occasionally trains aerialists when not managing a local country club. Her 1993 memoir was titled The Last of the Wallendas. ("She wasn’t happy about the title, but I get it," Wallenda says. "My family sees that as demeaning; I see that as an incredible marketing tool.")

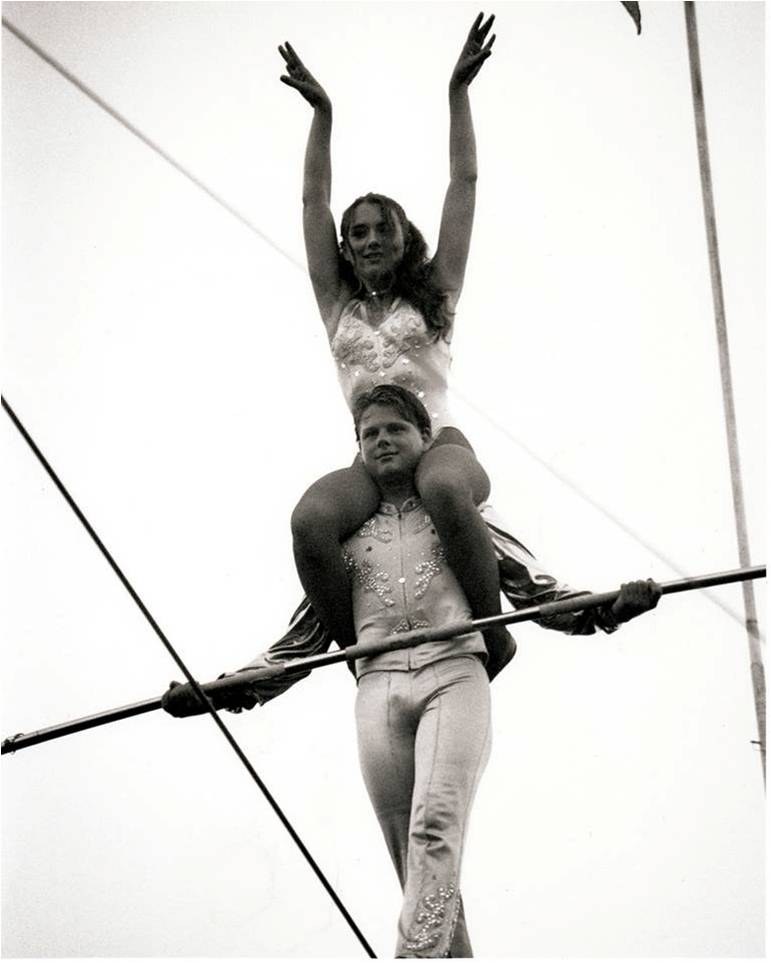

Despite the diminishing returns, Nik Wallenda and his sister, Lijana, spent their entire lives on the road with their parents performing; he was walking the wire by 2. He had intended to go off to college but in 1998 joined his Uncle Tino as part of a seven-person pyramid, the Wallenda family's signature stunt, in Detroit — where two members of the Wallenda family died and one other was paralyzed performing the same act in 1962 — and never looked back.

He says that he and Erendira, eighth generation in another traveling circus family, may have first been in a show together when she was 2 months old ("It was love at first sight," he quips); their families always saw each other, they were part of the same circuits, stayed at the same campgrounds. They married in 2000; 2008 was the first time in her life Erendira wasn't on the road full time.

"I wanted to give my kids a choice to go to school and do the things I wasn't able to," says Erendira, 34, who is slated to hang by her toes from a hoop dangling from a helicopter above the Charlotte Motor Speedway in October. "I miss everything — performing, traveling — but of course it was easier before you had kids in the back screaming and punching each other every second."

In 2006, Wallenda and his sister, Lijana, did a walk together in Detroit to promote McDonald's new coffee that almost ended badly when Lijana had some trouble on the wire. They made $18,000 for the walk, but more importantly, Wallenda remembers it as an epiphany of sorts, that he could make real money practicing this archaic art, and not from local carnivals or languishing circuses. Soon after, Wallenda says, he got a call from David Blaine, who wanted to meet him — so much of what Wallenda has come to learn about turning traditional entertainment into contemporary, commercial primetime events stems from this, and led to him signing noncircus representation.

In 2010, after Wallenda had set a few Guinness World Records and made a few Today show appearances, Discovery signed him to do a reality series called Danger by Design, each episode tracing the family members as they planned and performed a stunt in a different locale. The executive who developed the show left the network, and the series was shelved.

June 15, 2012, was the night that changed Nik Wallenda's life, or at least his career. About 13 million people tuned into ABC on a Friday night to watch a man that most of them had never heard of before preparing to walk a thin steel wire across Niagara Falls, as Karl Wallenda always talked about wanting to do. They didn't know about the two-year ordeal to make this event happen — how, after the National Parks of Canada unanimously voted against allowing Wallenda to do the walk, he lobbied and lobbied until they unanimously changed their minds. And they didn't know that the safety harness he was made to wear at the last moment was at the intractable insistence of the network. Wallenda was embarrassed and considered canceling; he understood that the appeal of this event lay in potentially watching a man plunge to his death on television, and the harness was negating that risk.

Certainly many of them didn't know what to make of Wallenda's frequent and emphatic prayers to Jesus throughout the windy, rainy half-hour walk, in between communicating with his father on the ground and fielding questions from ABC host Josh Elliott. This was not swaggering Evel Knievel in his Stars and Stripes jumpsuit launching himself over Snake River Canyon or Johnny Knoxville strapping himself to an exploding rocket. Nik Wallenda was devout, defiantly square, in the face of extreme danger — dad as daredevil. But they did now know his name.

Many viewers, unfamiliar with Wallenda or his background, were instantly taken aback by the vocal, vigorous praying; Wallenda insists that he didn't know his mic was on the whole time and wouldn't have done, and won't do, anything differently. (Numerous comments and tweets noted that taking a drink every time Wallenda mentioned Jesus would prove lethal.) He does admit his managers tried, at one point, to get him to downplay his devoutness for fear of turning off a general audience.

"I didn’t say, 'Jesus' 50 times on that wire because someone told me to or because I was preaching," he says. "That’s where I find my center and my confidence; that’s what keeps me calm and I was stressed out doing that walk. Howard Stern said, 'I’d be praying to Jesus too.' People made light of it but didn’t really make fun of it. I was just at the airport the other day and at whatever time, they had all their carpets out, all the taxi drivers, bowing towards the sun. Or the moon. I’m not sure how they do it. People respect that — that’s who they are and what they do. You don't have to listen. I think people are fascinated to see that's what I do to get through those situations."

And this, too, is apparently a family tradition. "I was doing a BBC interview and they played this clip of my great-grandfather talking to God while he was walking the wire. I never knew that, no one ever told me."

Publicly anyway, he resists tying his faith to politics, itself no small feat at this particular moment. "I get questions about our president on live national TV," he says. "That’s a rough question to answer but I’m quick, I’ll make it sound good, I’ll work my way out of it."

By the time he walked across the Grand Canyon in 2013, he wasn't famous exactly, but he was hardly an unknown entity — Discovery says there were 1.3 million tweets about the walk during their broadcast. "For Niagara Falls, I was the guy who walked across Niagara Falls," he says. "Nik Wallenda walked across the Grand Canyon."

Danger by Design was retitled Nik Wallenda: Beyond Niagara in 2012; Discovery aired one episode and canceled the series, airing the remaining episodes just once, in the lead-up to the Grand Canyon walk. "I think it was a pretty good series," he says. "You know, you always look back and say it could have been produced a little differently."

The thrill of the circus, or at least of the daredevil, is predicated on the notion that something terrible could happen right before your eyes; without that present threat, there's no real reason to buy a ticket. This is also why Wallenda believes his event specials have been successful in ways that his reality fare has not. "As an advertiser, you’re not worrying about TiVoing and your numbers are way higher because people are only going to watch this live," he says. "So for a network to sell a Nik Wallenda live special is a lot easier than selling a Nik Wallenda series. I don’t TiVo Nik Wallenda falling — I want to watch it live."

Wallenda's new home in East Sarasota is about 15 miles and symbolically a world away from the enclave of homes and trailers where his relatives live. "I have a gate for a reason," he says, smiling but not necessarily joking. The house sits on around 15 acres of land and is currently in the throes of a renovation; a separate 20,000-square-foot facility to house equipment as well as a production studio will be built eventually, and the high wire will soon be moved here from his parents' backyard. The family is living here during the construction, even if it means occasionally having to climb through a window and suffering the occasional drywall-related injury. Erendira practices aerial exercises on a hoop called a lyra, tied to the massive live oak tree. (Everyone in the Wallenda orbit seems to be doing something exhausting with their bodies at all times; while waiting for a table outside an Outback Steakhouse in Milwaukee the night before the state fair walk, Blake, the gloriously mutton-chopped 27-year-old son of Delilah's half-sister Tammy, bides time by doing handstands on the heads of two friends standing by the front door.)

For someone who grew up in an RV traveling from show to show, who's married to a woman whose family lived the same way, the notion of not just owning a home without wheels but having the time to stick around and work on it is a luxury that eludes most people who do what he does for a living. He gets to pick the kids up from school every day. It's a point of pride for him.

"I think that’s a brand in itself," he says. "That blows people away, like, That’s the guy who does that? He’s still with his wife and spends time with his kids? People expect the daredevil with tattoos who’s in the bar late at night with a different woman every other night, always chasing something. I would love to grow my brand even bigger than that, to a Ryan Seacrest level where, you know, I’m trying to get into other things." One show in development is a Mike Rowe–like reality series in which Wallenda would do a different dangerous job every week. He also wants to produce and host a kid-friendly game show à la Double Dare. "I think we need one again for Saturday mornings like we had when I was a kid. Kids need that."

When he talks about money, about his business acumen, about his brand, it doesn't seem as if he means to lord it over his peers and relatives who have not been as fortunate, but rather to remind how financially ruined and culturally eclipsed his profession has become, and what has been required to transcend that tradition while still honoring it. In April, I watched Wallenda walk atop the new Orlando Eye Ferris wheel, the main attraction at the grand opening of the city's new shopping center and 4D theater, broadcast live on the Today show. For this — a few minutes of strolling that would kill nearly any other human alive, accompanied by a couple days of international press — he pocketed $125,000.

The house is currently in some disarray due to the construction, so we sit in Wallenda's office. A framed poster for Cecil B. DeMille's The Greatest Show on Earth adorns a wall. Wallenda wants to not save just the circus as a tradition and as a viable business model, but rehabilitate the very word: It connotes chaos and distraction, clowns and carnies; a media circus is never good. But historically, circuses have been paragons of efficiency and expediency and entrepreneurship. An entire wing of the Ringling Bros. museum in Sarasota features a giant model detailing the logistics of trains coming into town full of humans and animals and unloading and setting up a self-sufficient community unto itself and then packing it all up and doing it all over again on an expanse of dry land in some other town. There is real order. There should be respect.

"When you go to the ballet, you wear a suit, and when you go to the circus, you wear shorts," Wallenda says. "That's the circus's fault, in my opinion, for not making it as relevant as it should be. In Europe they wear suits and ties." One afternoon in Sarasota, we attend a matinee of the Summer Circus Spectacular that is indeed a casual affair. The crowd largely comprises families and is enthusiastic — no one more so than the teenage girl behind us who didn't stop shrieking in laughter throughout. Afterward, Wallenda gives a sober assessment: He thought the clown was trying too hard, cataloged an acrobat troupe's nervous tics, felt a little bad for the aging aerialist legend. Generally, performers in a circus like this might be making $750 a week, barely enough to cover the cost of the campsite where their trailer is parked. Yet he reserved high praise for the two foot-juggling brothers whom he speculated may be able to pull in $150,000 a year each performing around the world — they do something unique.

Wallenda's dream is to not just make the circus cool, as he puts it, but to have his own — touring 30 to 40 weeks a year, that Erendira and Delilah can perform in regularly. "Doing these walks is awesome, but performing in a one-ring tent, it's like when big movie stars go back to Broadway," he says. "I have to build this huge brand in order to get back to where I want to be. And now I have a brand name; I am the Wal-Mart or McDonald's of our industry."

"From an industry standpoint, he's brought more popularity to it and a lot more people are realizing the significance of live entertainment as opposed to looking at something on YouTube," Blake tells me over lunch one afternoon. "It's tough to get young people to go out and see a live show, but they see something like [Nik] and they see the energy."

Finding bigger and more exotic locales to walk has now become Wallenda's calling card. He has been trying to figure out how to walk between Malaysia's Petronas Towers, but the problem is finding cranes tall enough for the rigging. He wants to re-create, move for move, Karl Wallenda's most famous walk, some 700 feet above Tallulah Gorge in Georgia in 1970, as a split screen alongside a hologram of Karl doing it, but might need two years to put that together. "That's how long it will take to get the funding and the sponsorships. I think it’ll cost somewhere between $500,000 and a million to do." (Some of Wallenda's relatives have speculated that he won't really be able to properly ape his great-grandfather's walk because he can't do a headstand on the wire like Karl did.)

"It’s about settings, it’s about world’s tallest, it’s about walking over the Serengeti, the Nile River full of crocodiles, it’s about walking over an active volcano," he explains as workers install hardwood floors outside the closed door. "The Colosseum in Rome with lions underneath me, it’s about the pyramids in Egypt. It’s about doing amazing things and showing the world amazing things that they may not be able to get onto a plane and go see."

The Walk is a two-hour meditation on the singular mind-set that compels people to do this, as well as on the intricacies of rigging a steel cable, but the man who inspired it wants nothing to do with his contemporary. Philippe Petit had planned to cross the Grand Canyon around the same spot — some of the rigging he was preparing for his walk is still installed at the site, abandoned — and was less than pleased when Wallenda did the walk himself.

“Now, if that person was another artist with a creative soul and was making a magnificent crossing there, then maybe my anger would turn into some kind of respect," Petit said in 2013, just before Wallenda's Grand Canyon event. "But I know the person who will walk there soon will just get — well, why not be cruel? — get his ass across, as they say sometimes in America, and nothing else... I don't know why people say he has guts, whoa, he has nerve, whoa — I don't think they were inspired. Certainly, I was not inspired because he was an uninspiring actor. I'm not impressed when I see something dangerous or something technically complex.”

"Philippe Petit is not a Nik Wallenda fan; he’s had nothing but horrible things to say about me," Wallenda says, smiling. "He’s an artiste, I’m not a true artist and so on and so forth. There’s a lot of animosity there. He's an arrogant Frenchman." Wallenda cops to occasionally appearing to slip or wobble for the sake of adding drama; it is hard to imagine the Petit portrayed on screen willingly sacrificing gracefulness. Yet Wallenda respects his hustle: Petit's memoir about the Twin Towers caper was published a year after the World Trade Center collapse. "People didn’t know who he was until all of a sudden he started capitalizing on it, which is smart, brilliant. My hat’s off to anybody who can market. He created a storyline and got an Oscar for it."

We watch the trailer for The Walk on the iMac in his office, and it's clear that the movie's agenda isn't just to cement Petit's authority-flaunting folk-hero legend, but to re-create, in full IMAX glory, the sensation Petit has described, the rush that drives people to walk the wire. On this at least, the two men agree. "There’s something about being up there that makes you feel alive, it makes you feel free," he says. "Petit talks about that so I relate in a big way. You feel limitless. You feel invincible at times. It's surreal."

From the high-wire platform in the backyard of Wallenda's parents' home, 25 feet above the ground, you can see a dozen ranch homes and trailers, many of which have some sort of Wallenda living in them. The house directly next door is the home of Delilah's brother Tino, now estranged from Wallenda; a big green storage locker emblazoned with a Wallenda logo sits in his backyard. Many of the houses have trapezes or wires or circus equipment. Two terriers, Lucy and Maggie, roam the backyard.

As opposed to nearly any crowd-pleasing death-defying act, there is something uniquely relatable about walking a tightrope — it's just walking in a straight line, we've all done it. There is not a huge range of results if things go wrong, you cannot only fall a little bit. "I’ve lost seven family members and I think four or five of them were only 30 feet off the ground," Wallenda says. "The death is the same."

The elevated wire in the backyard, then, is not necessarily for the practicing of craft — that is done just across the yard on a wire of similar length, all of two feet off the ground, where the margin of error performance-wise is identical but the consequences manageable. Up here is for psychological conditioning, for learning to not care.

On the lower wire, Delilah walks behind John, Wallenda's intern, as he crosses the wire, helping him adjust how he's holding the pole, which weighs about 40 pounds. I try standing on the wire while holding the pole and don't last two seconds; the pole feels impossibly heavy and awkward, the steel cable burrows into the bottom of my sock-covered feet, my inherited eye-hand coordination is decidedly not the caliber of Wallenda DNA. John is one of two trainees at the moment; Delilah generally spends her mornings training, then works afternoons and nights at the country club. Blake is also there practicing.

Blake is one of Wallenda's closest associates and protégés, but his mother has been in a now-settledlegal battle with Wallenda over his grandmother Jenny's house that even made TMZ. With Wallenda's growing profile comes a brighter light on the kinds of squabbles that have been part of his family for generations; he claims this one contributed to his estrangement from his Uncle Tino, Delilah's brother and next-door neighbor. "It needed to be restored, she had 13 years of back taxes, I was the only one who could help, so I did it," he says. "They all want the house; I want my money back that I put into the house. So, long story short, Tino, I’ve always looked up to him, but we had this meeting a month ago and I was in tears, I loved him, he was my hero growing up, but there’s a lot of resentment and a lot of hard feelings. I think a lot of that stems from the success."

His most ardent critic is probably Karl's grandson Ricky, a fellow performing Wallenda. "It would be a Jerry Springer show if we all came together in any one place," Ricky says. He admits the attention surrounding Wallenda's walks have been good for business but overshadow others' contributions to the family legacy. His biggest gripe, though, may be that his Barnumesque flourishes of self-promotion are at odds with his declared piousness. "I don't lie in my marketing and he does. One of Jesus's commandments is 'Don't bear false witness.' I don't have to be called the King of the High Wire; I'll call myself Rick Wallenda, Karl Wallenda's grandson."

During dinner at an Italian restaurant in Sarasota weeks before the Wisconsin State Fair walk, Wallenda and his wife and two sons and his father and Blake and a couple family friends sit around a large round table as servers bring out plate after plate, all on the house. A framed photo of Wallenda walking a high wire over Sarasota hangs on the wall behind him.

"That other side of the family, their goal is to destroy me over themselves winning, or getting better," Wallenda says. "That is winning to them. If they spent as much focusing on their own career, they'd be a lot better." He occasionally gets agitated referencing past stories about him that delved into the family melodrama, but he brings up the schisms unprompted and often. It's hard not to wonder whether he considers the strife and his role as a lightning rod as much a part of his brand as his accomplishments and his marketability. He defines himself by how he differs from others with his name, because who else can he really compare himself to?

And the resentment isn't just from within the family. "Nik's not blowing his own horn," Troffer says. "When he crossed Niagara Falls, this circus industry fell silent. Not, 'Wow, that was great.' They were so incredibly jealous."

Wallenda leans forward. "When we're on the wire performing the seven-person pyramid and the lights flicker on and off..." He raises his eyebrows. "That's how much jealousy there is in the industry."

"The business model I raised my kids with, there's no way that's survivable in today's market," Troffer continues. "The saying in the business is, 'How do you make a small fortune in the circus? Start with a large one.' Nik showed up with a team and a business plan where most performers — and I'll include myself in that — operated under a model that was created over 200 years ago and doesn't work. I can't imagine making a living."

Wallenda says the Niagara Falls walk in 2012 cost $1.1 million, with upwards of $30,000 out of his own pocket — he didn't make any money on it. But the dividends are still paying as he continues to forge a path both inside and outside of the business's traditional infrastructure, to keep his name in lights. An endorsement deal with a major camera company will soon be announced. There will be more and bigger walks, subsidized by smaller ones — Grand Canyons and grand openings. There will be live televised one-off events from dramatic locations and more modest attempts at making Nik Wallenda a regular part of our lives. There will be members of his family and his community who will continue to paint him as an archenemy. None of that will dent him.

"David Copperfield, that's who I want to be," Wallenda says. "He's a kid who grew up liking magic and now he's a billionaire. Not from investments, from magic."

Moreover, he considers this goal within reach — each deal signed is a step toward it. "I don't know how to say it without sounding arrogant, but I'm to a point where I don't think anyone in my industry has ever been. I think that's fair to say: the biggest name ever."

CORRECTION

Wallenda put $30,000 of his own money into the Niagara Falls walk; a previous version of this article misstated the amount. And Karl Wallenda had not been married before meeting Jenny's mother Martha.