Miriam Levin remembers the day she realized she had no country listed next to her city of birth in her American passport.

The 32-year-old, who was born in Jerusalem to American parents was travelling from Cambodia to Europe five years ago, when an immigration officer looked at her passport and smirked, "Jerusalem belongs to no country?"

"I didn't know what he was talking about until I looked and noticed that my passport just said Jerusalem. I thought it was weird but it wasn't until I got back to Israel and asked about it at the U.S. embassy that I realized that it was more than weird, it was political," said Levin, who has both Israeli and American citizenship.

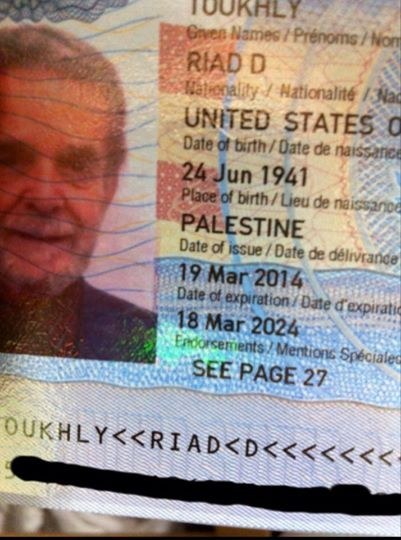

United States officials estimate that there are more than 50,000 Americans who list Jerusalem as their city of birth. Over the last 40 years, they have had everything from "Jerusalem, Palestine" to the inexplicable "Jerusalem, Jordan" listed in their passports as successive U.S. governments have struggled with how to label the long-disputed city.

Jerusalem remains divided between the Israeli government, who claims it as their capital, and Palestinian officials, who say it will be the capital of their future state. While Israel's parliament, head of state, and ministries are all in Jerusalem, much of the world does not recognize it as the official capital and continue to keep their embassies in the urban center of Tel Aviv, with only consulates in Jerusalem. It's a sign, they say, that the status of the city is unresolved, as official U.S. policy does not recognize any country as having sovereignty over Jerusalem.

"In terms of a legal status, a working status, and an international status, there are few cities in this world that are as complicated as Jerusalem," said one U.S. diplomat based there, who spoke in an off-record briefing last week. "I cannot think of many other places which have just the city, with no name of country, on American passports."

Earlier this month, the U.S. Supreme Court announced it would take another look at the request of 11-year-old Menachem Zivotofsky to have Israel listed as his place of birth alongside "Jerusalem" in his passport. Had Zivotofsky been born in Tel Aviv, the State Department would have issued a passport listing Israel alongside it. But the department's guide tells consular officials, "For a person born in Jerusalem, write Jerusalem as the place of birth in the passport."

Oral arguments in the court will be held this fall, but political activists on both side of the spectrum are already turning the issue into a broader question of how the U.S. will recognize Jerusalem.

"For us it is unacceptable for Jerusalem to be declared as Israel without taking into account Palestinian claims to this city. The status of Jerusalem must be determined in negotiations," said Xavier Abu Eid, a spokesman for the Palestinian government in Ramallah. "The U.S. has had a very strong position of not recognizing Israeli annexation of occupied east Jerusalem. That has been the position of the whole international community. As far as we are concerned Jerusalem is part of occupied state of Palestine."

The most recent round of peace talks, however, expired on Tuesday, April 29, and the two sides appeared as far away as ever from reaching compromises on a range of contentious issues, including Jerusalem.

Jerusalem today, and in 1857.

For those born in the holy city, there remains the question of why they can't determine for themselves which country they want listed in their passports.

Musil Shihadeh is one of just a handful of Americans who have successfully petitioned to have Palestine listed as their country of origin in their U.S. passport. Shihade was born before Israel's declaration of independence in 1948.

"When I was born it was Mandate Palestine. We had to go to court and argue this with the American authorities," he said. "They claimed there was no Palestine."

He said court officials told him that he could only choose from a list of countries currently recognized by the U.S., but his lawyers successfully argued that the law said the country of origin could be listed as the name of the country at the time of birth.

"Some people told me I made a mistake in doing this, because now, whenever I go to an airport I get stopped. People still associate Palestine with terrorism," said Shihadeh. "But for me it was important to identify myself with the country I was born in, this was an important issue of identity for me."

Since 1948, when President Harry S. Truman recognized Israel upon its declaration of nationhood, no U.S. president has accepted permanent Israeli rule over the entirety of Jerusalem. Israel's annexation of the city following the 1967 Arab–Israeli War brought all of Jerusalem under Israel's control. But U.S. policy has regarded the status of Jerusalem as something to be determined in peace talks between Israeli and Palestinian leaders. In 2002, Congress passed a law stating that a U.S. citizen born in Jerusalem may request his or her birthplace to be listed as Israel. The law was inserted into a broader spending bill that President George W. Bush signed, even as he announced that his administration would not carry out Congress' passport dictate. The Obama administration has adopted the same view: that Congress was intruding on the executive's responsibility for making the nation's foreign policy.

Over the years, many American citizens have found themselves caught in the bureaucracy of what to call Jerusalem.

Eric Kapenga, an American national whose work with Non-governmental organizations takes him throughout the Middle East, has struggled with the labeling in his passport.

"My American passport currently lists my country of birth as 'Jerusalem.' Older versions issued in the 1980s listed 'Jerusalem, Jordan,' which made it easier to travel to countries still at war with Israel or who prevented visitors who had been to Israel first," said Kapenga. "The current Jerusalem-only listing supports the international consensus that Jerusalem's status be determined through negotiation. But it also prevents me from visiting countries like Lebanon that are still technically at war with Israel. I have friends in Beirut who I've been wanting to visit for years, but unlike most Americans, I can't because of a single line in my passport."

He said that in an ideal world, U.S. nationals would have the chance to choose.

"The State Department would issue two U.S. passports to Americans born in Jerusalem — one that says 'Jerusalem, Israel' for travel to Israel, and one that says 'Jerusalem, Palestine' for travel elsewhere in the Middle East," he said.