Secretive surveillance devices used by law enforcement to track cell phones can also intercept conversations and possibly turn phones into a "bug" without the target being made aware, according to new documents obtained by the American Civil Liberties Union.

The documents confirm a long-held suspicion by civil liberty groups and privacy advocates about cell-site simulators, which law enforcement agencies have fought to keep out of the public eye.

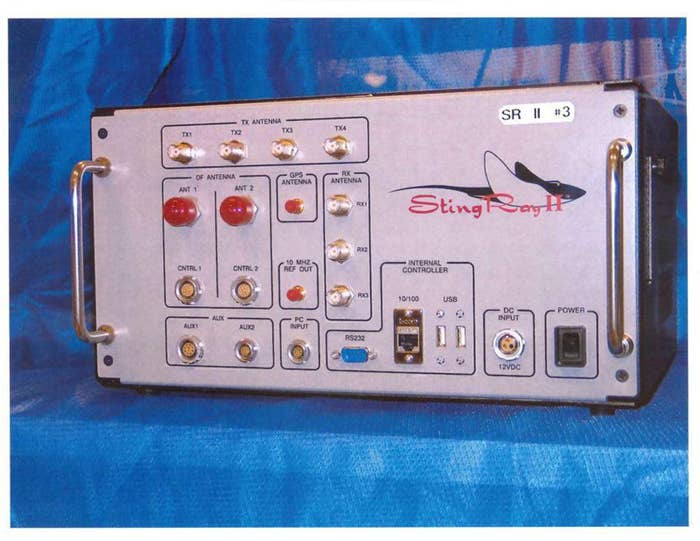

Known as Stingrays, Triggerfish, Wolfpack Gossamer and other names, the devices have been used by law enforcement for years as a tool to secretly track the location of mobile phones. The devices work by acting like cell towers and tricking nearby mobile phones to connect to them, revealing device information and location.

Documents turned over to the ACLU of Northern California under a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit Wednesday, however, revealed that the devices can also be used to eavesdrop on the conversations transmitted by cell phones and captured by the Stingray's electronic net.

"It may also be possible to flash the firmware of a cell phone so that you can intercept conversations using a suspect's cell phone as the bug," one of the documents from the Justice Department reads. "You don't even have to have possession of the phone to modify it, the 'firmware' is modified wirelessly."

The documents were released as part of a records request lawsuit filed by the ACLU against the DOJ two years ago.

"We've long been concerned that the government has not been up front with courts about the intrusive nature of these devices," Linda Lye, a senior staff attorney with the ACLU said in a statement.

The records released by the Department of Justice reveal some of the guidelines and procedures previously used by federal law enforcement agencies for Stingrays. For example, the documents show that when law enforcement was looking to identify the cell phone of a known suspect, DOJ required that the cell site simulator be used in at least three or four different locations, at different times, to identity the cell phone.

Under the previous guidelines, federal agents were required to get a court order showing the information was relevant to investigation. The new guidelines require a warrant, raising the bar and requiring investigators to show probable cause and specify what information they’re looking for.

A week before the documents were released, Homeland Security publicly announced a new policy for the secretive devices, requiring its law enforcement agencies to obtain a warrant before their use. The Department of Justice adopted a similar policy in September.

But the two new policies focused on the device's ability to locate cell phones, and skirted the Stingray's capacity to eavesdrop on actual conversations taking place on cell phones.

A previous memo sent out by the Department of Justice's Office of Enforcement Operations in 2012 states that not only could Stingrays allow authorities to listen in to conversations, but referenced how those "interceptions" could be authorized.

"Cell site simulators/triggerfish and similar devices may be capable of intercepting the contents of communications and, therefore, such devices must be configured to disable the interception function, unless interceptions have been authorized," it said.

It's unclear if, or how many times, the devices have been used to do so.

The documents also leave questions as to whether the devices used by local police departments, who have been purchasing the equipment in the last couple of years, had similar capacities.

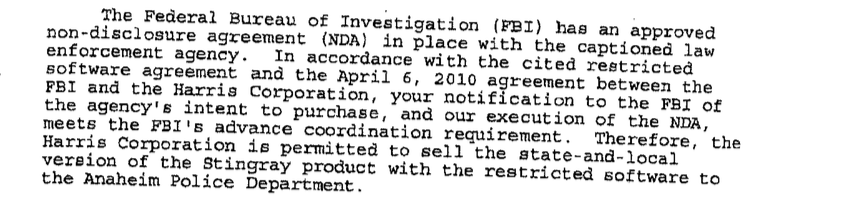

The purchase of Stingrays from Harris Corporation in Florida must be approved by the FBI in advance and require local police to sign a non-disclosure agreement not to reveal details about the device in public or in court.

Documents also suggest local law enforcement might have been purchasing a different version of the Stingray. Officials declined to discuss the capability of their devices with BuzzFeed News.

When the Anaheim Police Department in California sought to buy a Stingray in 2011, for example, the FBI approved a "state-and-local version of the Stingray product with the restricted software," according to documents obtained by BuzzFeed News.

Anaheim Police officials did not immediately respond to questions about the capability of their Stingray and whether it could intercept phone calls.

However, Sgt. Daron Wyatt told BuzzFeed News any interception of phone calls by Anaheim Police, like a wiretap, would require an electronic intercept order, which is often more difficult to be approved by a judge than a warrant.

That type of order, he said, would require police to show all other investigative tactics have been exhausted.

Whether local departments also had the ability to listen in on the phone calls is not clear.

The Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department used the device more than 100 times in 2013 and again in 2014, but declined in records request to reveal how or when the device was used.