At around 4 a.m. last Tuesday morning, Reza Alizadeh, a 26-year-old Iranian man who had been living in Australia on a bridging visa since 2013, walked to the entrance of Brisbane International Airport.

He had been troubled for some time. Suffering from depression, he fled the Iranian city of Ahwaz by boat in 2013 and headed for Australia. He spent around three months in various detention centres before he was released into the community on a bridging visa and moved to Melbourne.

It was at this point that his already fragile mental health rapidly declined. Two troubled years, dotted with incidents of self-harm, emotional breakdowns, paranoia, and suicidal thoughts finally ended, alone at Brisbane airport when AFP officers found him hanging from a bag strap attached to a railing at around 4 a.m. on Tuesday morning.

How did it come to this? BuzzFeed News has spoken to Reza’s friends who tried desperately to get him the help he needed, as well as medical professionals who say Australia’s immigration system is giving birth to a crisis in the refugee community.

“At the end he got worse and worse. On a number of occasions he tried to harm himself and he had scars all over his body, and none of the authorities cared,” a friend of Reza’s says.

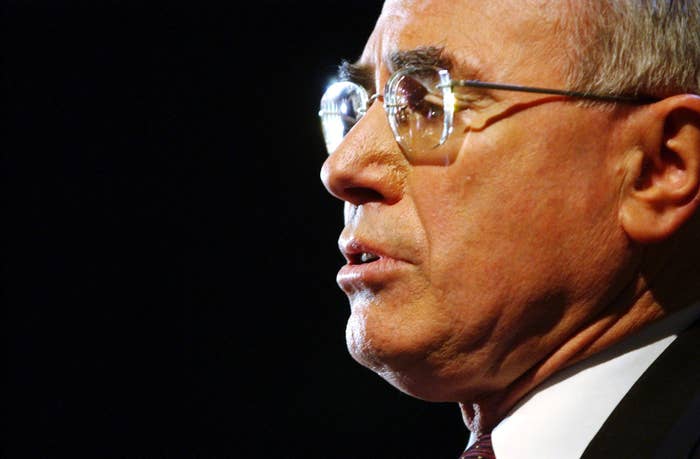

This is part of the new normal for Australia’s immigration system. For over a decade now – ever since former prime minister John Howard declared that "we will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come" – "boat people" have become a political football.

When Labor relaxed Australia's border protection laws in 2007, a tide of refugees attempted to reach the country by boat. Tens of thousands were intercepted and put in detention centres to be processed.

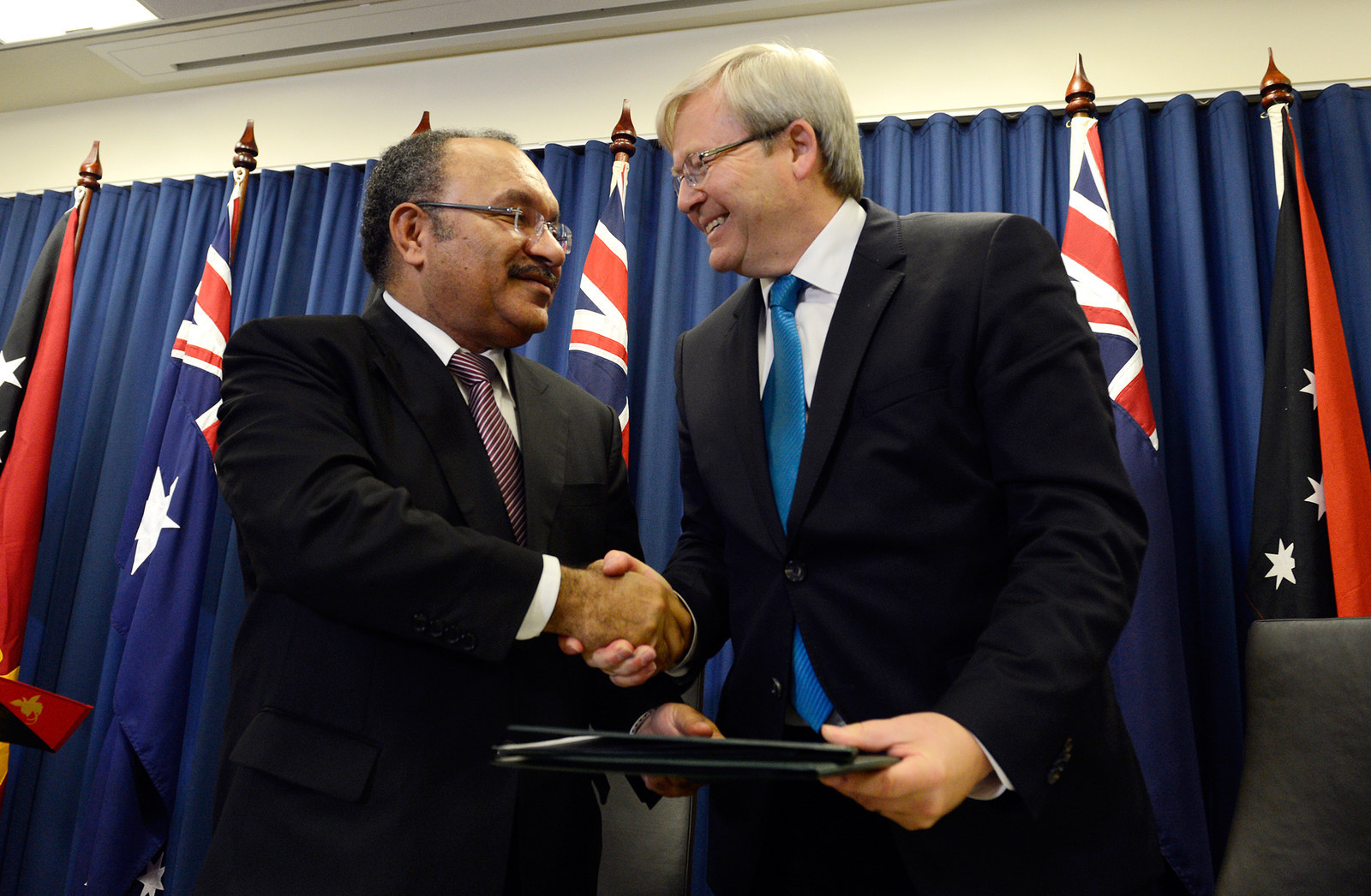

Eventually the sea of humanity making its way to our shores became too much and in 2013 a new policy was formed: no one who tried to reach Australia by boat would be settled here.

As a result, there are around 30,000 refugees currently living in Australia on bridging visas, which allow a person to live – with conditions – in the community while their refugee claims are being processed or until a more permanent home can be found for them.

The bridging visas have an upside: they’ve helped to get many refugees out of detention and into the community, where they’ve got the freedom to form friendships and communities which in theory should make life in Australia a little easier.

But advocates say the visas leave refugees in a state of abject poverty. Asylum-seekers who arrived in Australia by boat on or after August 13 2012 and are granted bridging visas are not permitted to work, meaning many rely on charity just to survive.

People on bridging visas have no right to family reunion and cannot leave the country. They are given access to temporary accommodation but are ultimately responsible for their own lodgings. In an emergency, asylum-seekers are given access to the Community Assistance Support program which helps people to meet their basic health and welfare needs. But first there has to be an emergency.

The system is deliberately and transparently punitive. The government’s stated objective is to deter asylum-seekers from ever wanting to come to Australia by boat.

It’s these conditions which have led to many asylum-seekers suffering from severe mental health issues, advocates say.

“We lock them up and drive them crazy, then we set them free and expect them to be OK,” says Pamela Curr from the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre.

Zachary Steele is the professorial chair of trauma and mental health at St John of God Hospital and a professor of psychology at UNSW. He tells BuzzFeed News asylum-seekers and refugees are among the most vulnerable people in our society and need our protection.

“Every survey that’s been done shows that they do have a very high rate of exposure to torture and trauma backgrounds that places them in a very high risk category for mental health problems,” he says.

“The stresses of insecure residency and the post-migration difficulties associated with the restrictions of bridging visas create a harsh environment that in turn is associated with poorer mental health trajectories.”

For Reza, this manifested in severe paranoia, depression, self-harm, and suicidal thoughts. And while tragic, Reza’s story is not unique.

"We lock them up and drive them crazy, then we set them free and expect them to be OK."

In February 2014 Rezene Mebrahta Engeda drowned himself in the Maribyrnong River upon notice of a failed asylum application.

In June 2014 a 29-year-old Sri Lankan man died as a result of self-immolation, suffering burns to 90% of his body. He had been living in community detention on a bridging visa awaiting the outcome of his refugee claim.

In March, Omid Ali Avaz, a 29-year-old Iranian man on a Humanitarian Stay (Temporary) visa, killed himself in Brisbane.

Earlier this month, Hazara man Khodayar Amini set himself alight while on a video call to two refugee workers.

Before his death, Khodayar reportedly told the refugee workers, "Red Cross killing me. Immigration killing me. I want to kill my life. I don't have any option. They don't give me chance. I can't stay in detention centre."

One of the major problems, Pamela Curr says, is that many asylum-seekers suffering from mental health issues are afraid to reveal their troubles to the people who are supposed to help them.

“The asylum-seekers are really cursed. If they have an agency that’s looking after them and they go to that agency and say, 'I’m feeling suicidal, I want to jump in front of a train, I can’t sleep, I’ve got voices in my head’ – all the marks of mental ill health – those agencies will notify the immigration department, and the next thing you know, the department will rock up and cart them off to detention. They’re in a real bind.”

Without any family in Australia, it was Reza’s friends who tried the hardest to get him help.

Reza took himself, or was taken to, at least three Melbourne hospitals or medical centres in the weeks before his death. Ten days before he died, Reza broke a mobile phone in half and attempted to slash his throat while in hospital. A short time later he was released to look after himself, friends say.

The hospitals contacted by BuzzFeed News were unable to comment, citing privacy concerns.

In Reza’s final weeks, friends say they contacted the immigration department, police, and Reza’s caseworker with AMES Australia, a government-contracted nonprofit which helps recently arrived refugees settle into Victoria.

A spokesperson for AMES told BuzzFeed News the organisation did all it could for Reza, but that his erratic behaviour in the period before his death made it very difficult to provide the care he needed:

“[Reza] was provided with the full range of services all of our asylum-seeker clients are afforded. As a person with a range of health issues he was given close case management and referred several times to healthcare providers."

"It's all black and white… on a number of occasions [Reza’s friend] has taken Reza to hospital, to police, to AMES, to his case worker, to immigration, and they basically said ‘he’s alright’."

Shortly after Reza was released from the third hospital, he decided to fly to Brisbane. He felt this was the only place he was safe from the people he believed were following him. His friends helped him fly to Brisbane while informing anyone they could of their concerns for his wellbeing.

“He [Reza] got in touch with his cousin and he sent text messages that he was going to take his life. Then his cousin, on a number of occasions, contacted his case worker,” Reza’s friend says.

Melbourne police were informed of Reza’s situation, and Queensland police were subsequently informed.

It’s believed Queensland police officers contacted Reza after he arrived in Brisbane, meeting with him in a hotel room in Fortitude Valley to assess his mental health. After a conversation, Reza's friends say, the officers left him alone, deciding he was not a danger to himself or others.

Following the meeting, Reza’s friend, also named Reza, says he contacted the department of immigration and AMES to warn them that Reza planned to end his life, but was told that nothing could be done.

“It's all black and white… on a number of occasions [Reza’s friend] has taken Reza to hospital, to police, to AMES, to his case worker, to immigration, and they basically said ‘he’s alright’,” another friend says.

The two Rezas texted constantly over the weekend before final contact was made on Sunday evening. It’s not clear what happened between Sunday evening and Tuesday morning, but we may learn more when Queensland police hand over a report for the coroner.

It’s too late for Reza, but mental health experts say the system needs to be changed to look after people on temporary visas.

“Your life is permanently on hold and you have a subjective fear that you may be returned to a situation where you fear for your wellbeing and the wellbeing of your family,” Prof Steele says.

“People do have to have their claims assessed and that does put enormous stress on them. There’s no way to solve that problem but there is a way to recognise it and to put a health and welfare framework around it that recognises that this is a vulnerable population.”

Michael Dudley, the chair of Suicide Prevention Australia, believes "torture" is not too strong a word for Australia’s current immigration system.

“The way in which the policy is giving rise to harm that the government and the department are aware of – it’s collateral damage of which they are fully informed. It’s a direct aim of the policy. It aims to cause suffering to make people leave the country."

Dudley says the solution is at once complex and simple: time and money. He believes refugees have a sword of Damocles hanging over their head which could be resolved if more funding was dedicated to processing refugee claims as fast as possible.

“The UNHCR [United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees] needs proper funding by governments like Australia. We don’t actually have a system that is designed to do that. It’s not properly resourced,” he says.

“Mental health support could help people in these situations. Whatever support we can offer, whether mental or practical, in these dire situations, should be offered.”

Queensland police declined to comment for this story, saying it would be inappropriate as they prepare a report for the coroner.

The Department of Immigration declined several requests for comment, citing the Queensland police investigation.

If you or someone you know needs help, contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or visit Lifeline.org.au.