The hundreds gathered at Cooper Union on Saturday called themselves "allies" of Aaron Swartz, the 26-year-old activist and programmer who took his own life earlier this month.

On the heels of a funeral held outside Chicago on Tuesday, where Swartz's father charged that Aaron was "killed by the government," speakers in New York once again inveighed against federal prosecutors who, they said, drove Swartz to suicide.

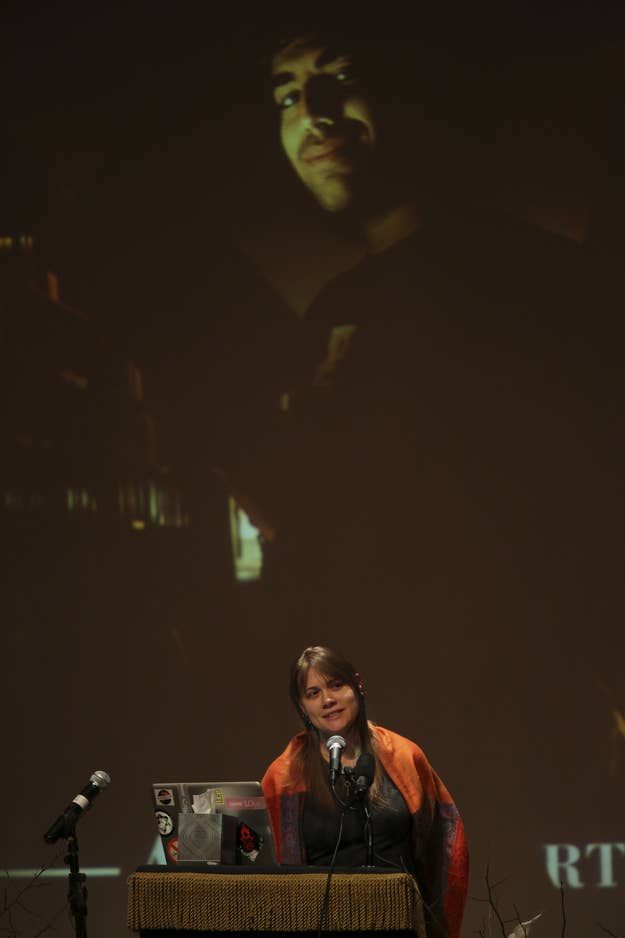

Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman, Swartz's partner, said that Stephen Heymann, an Assistant U.S. Attorney, was "hellbent on destroying Aaron's life."

She recalled a court hearing in which Swartz shrugged off her embrace.

"I don't want to show Steve Heymann that," Swartz told her.

Several eulogists had known Swartz since his teenage years — a computer prodigy, he helped build RSS, Creative Commons, and reddit all before turning 20 — but the lines that drew the most applause addressed Swartz's legal demons, which had haunted him since a 2011 indictment for downloading millions of scholarly articles from a wiring closet at MIT.

"My first question was, why isn't MIT celebrating this?" said Edward Tufte, a professor emeritus at Yale. Along with Heymann and U.S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz, MIT has come under fire for participating in Swartz' prosecution, despite the university's longstanding commitment to open access.

Roy Singham, the founder of ThoughtWorks, an IT consultancy firm that employed Swartz, rallied against the "duplicity of our society that protects those that accumulate wealth, and treats those like Aaron in a completely different fashion."

While tech leaders like Mark Zuckerberg, Steve Jobs and Bill Gates "bent the rules for their own good," said Singham, "none of them faced 35 years in prison." Swartz's life, he said, was "the exact opposite of these people," dedicating his "incredible talents and privilege for the advocates of those without."

Although his legal travails loomed large over the service, Swartz was remembered by others as a rational altruist, an idealist who appreciated the mechanisms of change.

"The revolution will be A/B tested," Stinebrickner-Kauffman remembered Swartz as saying.

In a 2012 keynote address that has been shared widely since his death, and was excerpted at the service, Swartz recounts his role in the "Stop SOPA" movement, which successfully thwarted online trafficking legislation last year.

"I did what you always do when you're a little guy facing a terrible future with long odds and little hope of success," Swartz says. "I started an online petition."

An architect of the modern internet, Swartz saw more than most the practical power of connectivity, and the possibility to "change the world at scale," as his friend, Ben Wikler, said.

"Aaron believed in trying to maximize the good he accomplished," said Holden Karnofsky, co-founder of the charity evaluator GiveWell, which was the sole beneficiary of Swartz's will.

Music, too, filled the auditorium on Saturday. As mourners filed in, the protest songs of Pete Seeger — whose grandson read a statement from the famed songwriter — thrummed over the loudspeakers. Twitter's Glenn Otis Brown quoted from the Leonard Cohen song, "Anthem." And OK Go singer Damian Kulash performed an acoustic cover of Lavender Diamond's "Everybody's Heart's Breaking Now."

Having staged so many acts in his short life, Swartz could be all things to all people, said Quinn Norton, a longtime friend. Writers saw in him a scribe, sociologists a colleague, and activists a leader.

"Aaron was doomed from the very beginning to be just Aaron," Norton said.

Soon after the indictment, Tufte recalled reaching out to the founder of JSTOR, the digital library whose files Swartz had retrieved. JSTOR settled with Swartz privately in 2011, and said in a that they "regretted being drawn into [the case] from the outset."

"Aaron's unique quality was that he was marvelously and vigorously different," said Tufte. "Perhaps we can all be a little more different too."