The anchor’s raspy voice is distinctly Colombian. She pauses for a brief second and continues in Spanish.

“In a world where bureaucracy keeps growing and there is an excess of information, we also run the risk that our voices drown. The great challenge is to find out a way to respect other people's projects, in a critical way, allowing all voices to be heard. Otherwise we run the risk, like Maggie, where a specific group in society looks for more destructive ways to be heard.”

The woman speaking, 34-year-old Diana Rojas, isn’t referring to some great philosopher or activist icon. She’s talking about Maggie, the baby on The Simpsons. And Rojas isn’t a traditional radio journalist — she’s an inmate at a women’s prison in Ecuador.

Diana Rojas analyzes The Simpsons on Palabra Libre. Image courtesy Ministry of Justice; audio courtesy Palabra Libre.

This was the 67th episode of the award-winning radio series Palabra Libre, hosted and produced by female inmates from a studio inside the Center for Social Rehabilitation. The prison, which holds approximately 700 inmates, is in Latacunga, nestled close to Cotopaxi, the world’s most monitored volcano.

The episode, titled “The Simpsons' Philosophy,” aired in March 2015 and became the most popular one since the series began in September 2011. After the episode was uploaded online, it had more than 1,500 downloads.

Rojas’s voice fades and another anchor, Andrea Carates, jumps in. The handover sounds professional and practiced. “Silence is a sign of complex thinking, silence is gold,” says Carates, in a Latin American accent distinct from Rojas’s. “As Heidegger, one of the biggest philosophers on the pre-Socrates era said, ‘Silence is essential to live a truly authentic experience.’”

In the United States, popular podcasts like Serial can bring in more than a million listeners per episode. But in a country like Ecuador, where mainstream shows like Desde Mi Visión and Buenos Dias, Buenas Tardes had a few thousand downloads per episode weekly, Palabra Libre’s reach is significant. What’s truly extraordinary, however, aren’t the listener numbers: it’s where the program is broadcast from.

Palabra Libre — translated it means “free word” — began as a way to humanize those in the nation’s penal system and nurture inmates' life skills. The program is a collaboration between Ecuador’s Ministry of Justice and provincial government of Pichincha to help “personas privadas de libertad” — people deprived of physical liberty — to reintegrate into society by participating in the arts. The program first began at a men’s prison in Ibarra; based on its success there, a similar program was incorporated into the women’s prison in El Inca in 2011.

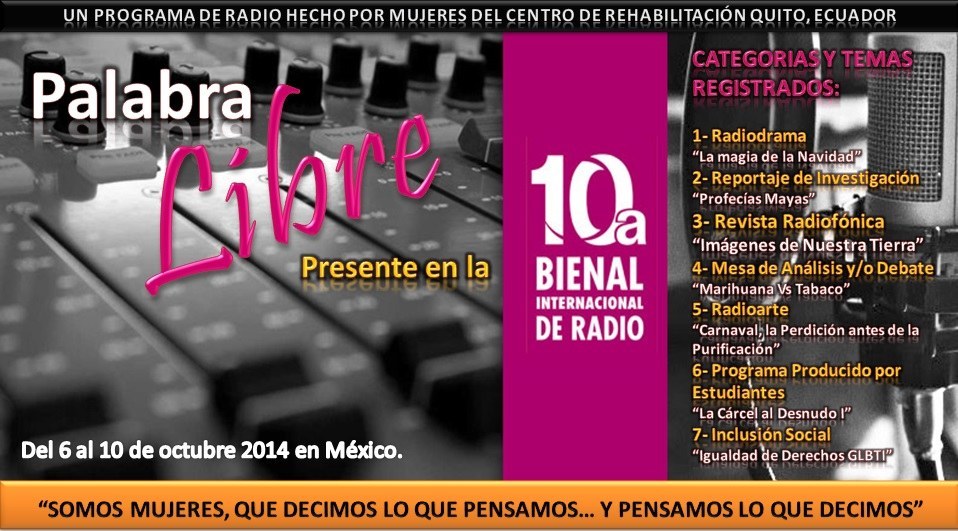

Palabra Libre has defied its creators' expectations. In October 2014, Palabra Libre won first place in the category “programs produced by students” at the 10th International Radio Biennial Competition in Mexico, which included 980 programs hailing from 19 countries across the world. Given by the Secretariat of Public Education and the National Council for Culture and the Arts in Mexico, the award recognizes new developments in radio and communication in Latin America.

But its greatest impact may be on the participants themselves, approximately 40 of whom have been through the program. "Even if I am here in a sea of sadness, my soul rejoices with everlasting happiness, because I can communicate the value of the word 'freedom' throughout this radio program,” 49-year-old Alejandra Tamariz said in another episode. “I can express what I think, what I believe, what I feel, because I have the opportunity to raise emotions and expressions." Even though she is incarcerated, she said the program makes her feel “without limits."

Sitting outside the winding monochrome corridors of Ecuador’s Ministry of Justice, Human Rights and Religious Affairs in Quito, Tamariz’s round wooden earrings swayed in the wind as she reached into an oversize bag of K-chitos, her breakfast on that foggy morning. As she picked out a bright orange crisp, she laughed heartily and exclaimed, “I hate this color. No more orange, please!”

The color, she said, reminds her of the uniforms in Latacunga. It’s been five months since her pre-release from the facility, yet small things often take her back to the time where sitting outdoors and relishing junk food would not be possible without a surrounding fence or a guard watching.

Tamariz is from Guadalajara in Mexico, but she hasn’t been home or seen her family in almost five years. Involved in a petty drug smuggling act, she was caught at the Quito airport with a small quantity of cocaine in her bag, enough to get her implicated for seven years under Ecuador’s stringent drug-trafficking laws. While she has been released on probationary grounds for good behavior, she is unable to leave Ecuador until the completion of her formal sentence.

Her dark eyes, thickly outlined with green and blue eyeliner, light up when she talks about her former role as producer and coordinator of Palabra Libre.

“The radio show gives me hope,” she said. “It provides me with a vision for my future, because I messed up the past.”

Alejandra Tamariz delivers her speech about free expression on Palabra Libre. Image courtesy Ministry of Justice; audio courtesy Palabra Libre.

Sitting next to Tamariz is her former cellmate and friend, Rojas, a Colombian with fiery red hair. Like Tamariz, she had been released for good behavior but was stuck in Ecuador until her formal sentence came to an end. She’d been quiet, but at the mention of the show, she becomes emotional, saying, “You return to your routine in the prison afterward, but at least for a few moments you thought about other things.”

The show began as a vocational training workshop. Tamariz and Rojas were taken through all the elements of production, from scriptwriting, recording, and editing segments to voice modulation, linguistics, and sound. These classes were the rare respite they had been craving. “I made a stupid mistake and landed up in prison and missed my son’s entire childhood,” said Tamariz as she fidgeted with the shoelaces of her worn canvas shoes.

Before the show, Tamariz threw herself into the few recreational activities offered in Latacunga, like aerobics and basic computer training. They were much-needed distractions to help the time pass until Sundays, when she’d be granted five minutes to Skype with her now-11-year-old son. (“He thinks I am working in radio in Ecuador,” she said. “He doesn’t know that I have done something wrong.”) By the time she became the coordinator for the radio program, she was already teaching a computer class to other inmates.

Since its inception, the program hit on themes of free expression and was aimed at not just other incarcerated people, but also those outside the prison. “It is not only for us, but for the people outside to make a connection with us,” said Tamariz.

Radio has a rich history in Latin America, acting like the old town square, where civil complaints could be aired.

For decades, radio has given a “voice to the speechless,” said Catalina Valenzuela, a contributor and partner at TECHcetera, an independent digital platform targeted at Spanish-speaking, non-tech-savvy audiences. “Through various shows people, citizens, have been able to air their problems — personal and political — and to discuss them with other listeners or with the shows' anchors. Radio shows are still today a key political place for citizens, policymakers, and opposition leaders alike.”

The traditional format is especially important in regions where digital literacy levels are low. “Radio signals can travel across the Andes more efficiently than TV signals, and while television became popular much later, radio accompanies our life because it runs 24/7 like internet access in the First World: It is ubiquitous,” Valenzuela added.

Eric Samson, coordinator of multimedia journalism at the University of San Francisco in Quito (USFQ), Ecuador’s capital city, has studied the evolution of Palabra Libre. He explained that the concept was first tested with female inmates at El Inca Prison, which was an older, less strict facility north of Latacunga that has now closed. (There were no uniforms and inmates were free to access the internet, use the phone, and see visitors.)

“It was all about conveying a message of humanity from the imprisoned women to the outside world, that even though we have made mistakes, we are not beasts and have a voice and want a chance,” Samson said. “It’s a clear-cut example of democratizing freedom of expression and incentivizing artistic aptitudes."

When the show began in 2011, a team of 14 women devoted themselves to the production. Complete autonomy was given to the radio team when it came to choosing themes and topics, conducting research and interviews, writing scripts, and subsequently presenting. “We wanted to deliver a product that was informative, created conversation and reflection, and made listeners aware that there is neutral communication coming from within the prison,” said Tamariz.

All the necessary infrastructure and equipment to make radio was provided by the Ministry of Justice, and a mini radio booth and studio were set up with its help and resources. Local Ecuadorian inmates got paid for their work, while non-Ecuadorians like Tamariz didn’t. “For me, it was purely my passion that made me put my heart and soul into this,” she said.

A concerted effort was made to veer away from personal stories and anecdotes and toward broader concepts. “It’s a program for society, and not for the inmates. It helps our own learning and also we don’t want any pity; we want respect,” Rojas said. Still, during Christmas, when everyone is homesick, the radio show incorporates audio snippets from telenovelas to lighten the mood and lift spirits.

The 60-minute segments have covered topics from freedom of speech and LGBT rights to football, sex, and the history of the Galapagos Islands. Tamariz said that they research topics at the library. “We still prefer the Mills & Boon [British romance] novels and [Gabriel García] Márquez romance novels and Harry Potter series in prison,” Rojas added with a smile.

The segments can vary widely. “I created this section called ‘The Time Capsule’ where we take listeners through time to historical figures like Al Capone and Leonardo da Vinci,” said Tamariz. Sometimes they even host debates between themselves and 22 Mil Voices, a program broadcast from a men's prison.

Listeners send feedback to the prison. Some criticize the lack of spontaneity in the program, complaining that inmates sound too scripted, but most laud their efforts. In particular, female listeners have called or written in thanking inmates for covering controversial topics like abortion, which is prohibited under Ecuador’s criminal code.

After Tamariz’s probationary release, the legacy of Palabra Libre has continued, but with some challenges. There are now only eight people inside the prison who are producing the show. Some of those involved behind the scenes think the prison should take the program in a new direction.

Luisa Pluas Orozco has been the program’s coordinator since Tamariz’s release in mid-2015. Prior to becoming the coordinator, she used to be involved in the radio program’s research and narration. Over email, she explained that current inmates are experimenting with a show called When Science Transgresses Reason, a debate show. “It’s a big responsibility because I am a guide who has taken the reins and am creating a path for future producers,” Orozco wrote.

Meanwhile, USFQ is finalizing an agreement with the Ministry of Justice that will allow inmates to take university classes from within the prison. “The initiative is very healthy and I am hoping we can soon provide classes on packaging at the centers,” Samson said. He said that bringing students into the prison to teach the inmates will, in turn, benefit students themselves. “I want them to know what it’s like inside a prison and how it’s important to empower inmates.”

Tamariz and Rojas both say their time in radio is far from over. As part of the process of social and professional reintegration of detainees promoted by the ministry, inmates on probation will air a new radio program called Pata Llucha (“bare feet”). The focus will be on indigenous groups in Ecuador.

Pata Llucha will be recorded in Quito at the offices of Radio Pichincha. Tamariz and Rojas said they were looking forward to working in a professional radio studio and going out into the field to report. “We don’t have to rely on people coming to the studio in the prison," said Rojas excitedly. “Here we can actually go to them.”

“My journey will not end when I walk free,” said Tamariz, referring to the end of her probation, as she finished her last K-chito and licked her fingers. She hopes to continue pursuing radio, whether teaching the skill to other inmates back home in Mexico or trying her luck at becoming an independent radio entrepreneur. Her dream project is to start a program aimed at Ecuadorians abroad.

“I want to focus on Ecuadorians who live away from home in other parts of the world. If I can take that to jails in Mexico and offer a support network, I will really come full circle,” she said.

As the clock struck 11, she stood up. It was time for her to do her weekly probationary signing at the ministry.

“Even though I got stuck in Ecuador, I made some good friends and have done some rewarding work,” she said, wiping her fingers on her black spandex pants. “Now it’s time to continue and give back.”

This article was supported by the International Reporting Project with translation and assistance from Carolina Loza Leon.