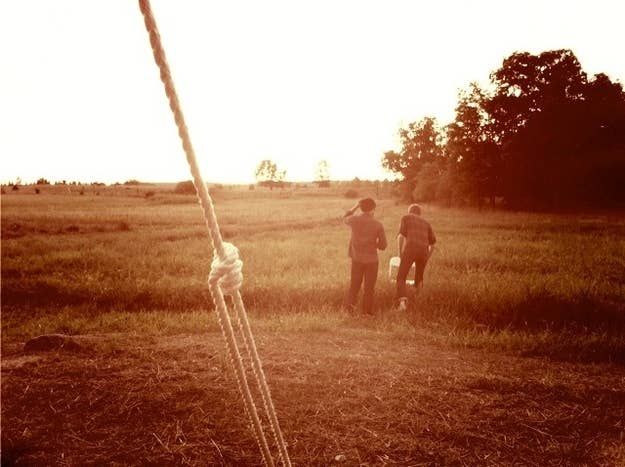

There’s an odd allure to loudly denying your particular time and place: Tom Waits cruises around California with a stack of vinyl records, an old sarsaparilla bottle, and a “yellowing newspaper announcing the inauguration of John F. Kennedy” bouncing around his S.U.V. Jack White recently declared the long-playing album “the pinnacle of musical expression” and continues to record only in analog, hand-slicing his tape into bits with a razor blade. Meanwhile, each day, nearly 40 million Instagram users blur and tint and reshape benign images into the kinds of yellowing snapshots you can buy at flea markets for a quarter apiece. In nearly every regard, the new now is then.

Feeling nostalgic for a time you never actually knew is a deeply unsettling contemporary phenomenon. For some people, it means clawing through junk shops in pursuit of the perfect brass-lensed tailboard camera, but for most of us, it means applying the Lord Kelvin filter to a hasty snapshot of last night’s dessert. So is that vague, manufactured nostalgia culturally toxic, per Simon Reynolds' Retromania (and the cavalcade of nervous think-y reviews it inspired)? Maybe – but it’s weirdly gratifying, too, tapping into the sense "that a photograph is itself a precious object," as New York Magazine put it recently.

One of my undergraduate writing students recently described Instagram as “the Auto-Tune of photography,” and the comparison made a whole lot of sense to me. It’s a broadly democratizing device: Instagram’s filters are intended to soften all the ugly, too-real bits, to make plainly composed images more compelling (last year, founder Kevin Systrom, talking to the New York Times, said “We set out to solve the main problem with taking pictures on a mobile phone,” which is that they are often blurry or poorly composed. “We fixed that.”)

At a certain point (as with Auto-Tune), all that relentless filtering does begin to compromise (or at least alter) the integrity of Instagram’s hey-here’s-how-I-see-the-world conceit, but I think that’s mostly fine; very few things about our online lives — or, for that matter, art — are authentically rendered, and the deeper we get into the 21st-century, the more preposterous it seems to continue holding up authenticity as some kind of grand, aspirational ideal. What’s more interesting (and this is true for Auto-Tune, too) are the facts of the filters themselves. As the Atlantic clarifies, a filter is not just a filter, it’s a meta-commentary — a deliberate aesthetic and narrative choice. So what does it mean that Instagram’s most popular settings make your photos look like they were taken on an archaic, possibly malfunctioning device rather than a smartphone?

We’re in a cultural moment that prizes artisanal, small-batch, hand-cranked everything, and when it comes to art and technology – already a dicey intersection – plenty of folks are pining for old-timey, nuts-and-bolts craftsmanship, even if they’ve never experienced it firsthand and aren’t prepared for all the work it takes to actually achieve. For whatever reason — the acceleration of culture, the odd loneliness of a virtually lived life, skyscrapers, cubicles, the decline of manual production — we’re collectively nostalgic for “simpler times” (of course, the notion that life’s ever been simple is probably humanity’s wildest and most self-perpetuating cultural con). We want our art to reflect that foggy longing; what we don’t want, necessarily, is an actual backwards slip.

That makes for a compelling paradox: War photographer Damon Winter has admitted to employing his iPhone (and Hipstamatic) in favor of his SLR — he described the process as “more casual and less deliberate,” noting that pulling out his phone made American soldiers less self-conscious than aiming his camera — and the resultant images are appropriately muted and surreal. They wouldn’t exist without a specific, familiar technology — or wouldn’t exist in the same way, at least – yet they’re fully stripped of its hallmarks (clarity, focus, perfection). These days, instead of eschewing technology, we’re using it to deny itself — it’s figuring out a wash that makes fresh jeans look old, it’s pre-weathered furniture, it’s a GarageBand setting that makes your brand new guitar sound more like an electrified relic. Nostalgia has become institutionalized to the point that an expertly captured and reproduced image — a technically perfect picture — is what feels hokey, and not a faux-yellowed, heavily filtered one. Yikes?

Presuming that nostalgia is cyclical (forty years is the magic number, according to Adam Gopnik) and eternally self-refreshing, then we’ll never stop filtering — the filters themselves will change, maybe, getting better at reflecting an even-less-distant past. Instagram’s neatly and easily updated nostalgia is, in many ways, its biggest selling point, finding new ways to mimic the past.

Maybe this is how we reckon with the future now.

Amanda Petrusich is a music critic, author, and girl about town.