Since the late 1990s, the number of animals used in experiments at the biggest research universities in the U.S. has increased by more than 70%. So claim researchers with People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) in a new study published in the Journal of Medical Ethics.

The study also concludes that 98.8% of the animals used at the 25 largest institutions that receive federal biomedical research funding are missing from government statistics. That's because the most widely used lab animals — mice, rats, and fish — are excluded from regulation under the Animal Welfare Act (AWA).

"Relative to somewhere like Canada or the U.K., the reporting requirements in the United States are so minimal that it's very difficult to get any truly reliable data," Justin Goodman, PETA's director of laboratory investigations, told BuzzFeed News.

According to the USDA, which enforces the AWA, 891,161 animals were used for research at U.S. labs in 2013, and another 147,815 were held by a research facility but not used in any experiments.

These numbers have been falling steadily over the years, leading some organizations to conclude that animal research is in decline. The website of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science states: "The number of animals used in research has actually decreased in the past 20-25 years. Best estimates for the reduction in the overall use of animals in research range from 20-50%."

But the USDA numbers are gross underestimates of total animal use, thanks to the strange history of the AWA. When it was signed into law in 1966, "animal" was defined as dogs, cats, monkeys, guinea pigs, hamsters, and rabbits, plus "other warm-blooded animals" that the Secretary of Agriculture determined were being used in scientific experiments.

Mice and rats are the mainstays of biomedical research, and yet they were never deemed to be “animals” by the USDA — even after the AWA was amended in 1970 to expand the definition to all warm-blooded creatures.

And in 2002, after lobbying by organizations that support animal research, Congress tweaked the AWA again to specifically exclude mice, rats, and birds.

While the USDA hasn't been keeping a tally of excluded species, institutions that receive research funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) are required to file assurances that they are complying with standards for animal welfare. These reports, submitted every four years, include an "average daily inventory" of animals in their labs — including species not covered by the AWA.

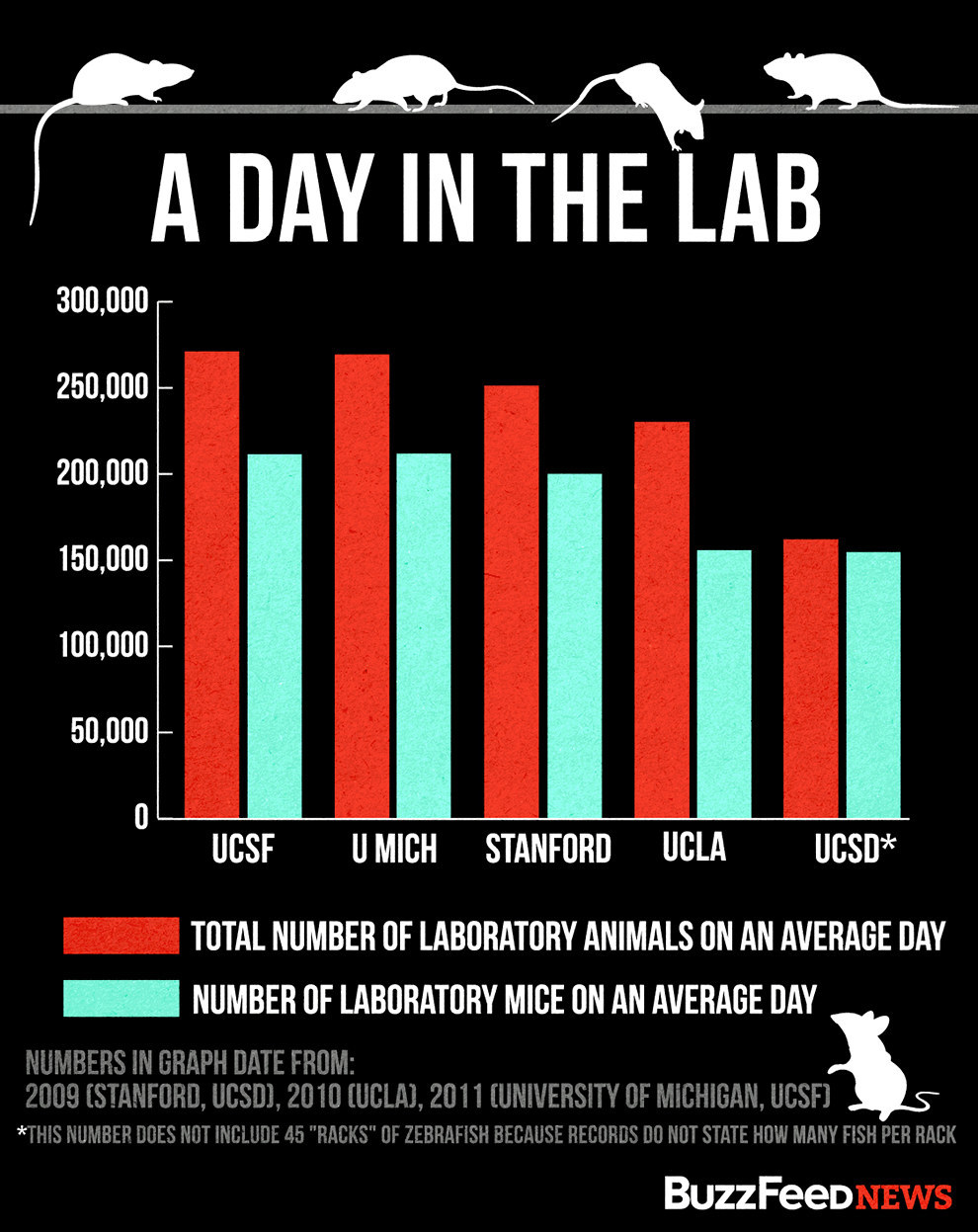

PETA's research team filed Freedom of Information Act requests for the most recent three reports submitted by the 25 largest recipients of NIH funding. Here are the numbers from the top five institutions, by total animals used, calculated by BuzzFeed News from the latest reports obtained by PETA:

BuzzFeed News asked these five institutions about their numbers. UCLA responded with updated figures from 2014, which indicate that its animal use has almost halved from the 2010 figures obtained by PETA.

All five universities are members of the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, and so also report numbers to that organization, as well as the NIH. UCSF has published those figures on its website. It used a total of 633,507 mice over the entire year in 2011 — three times the daily average census, which institutions report to NIH.

Many research institutions have been reluctant to share their numbers with the public, given the fear of being targeted by militant animal rights activists. UCLA's website on animal research describes incidents including two firebombings.

But some are less reticent. The University of Michigan, for example, two years ago launched a website on animal research that summarizes the numbers it sends to the NIH, noting that 98% of the animals it uses are mice, rats, and fish.

"We do hope it can be a model of voluntary transparency and information," Brian Fowlkes, the University of Michigan's executive director of laboratory animal use and care, told BuzzFeed News by email. "After all, we are a public university and our research relies in large part on public funding."

Mice are used more than any other laboratory animal, by a long shot.

They've grown in popularity since the late 1990s because of the revolution in genetics triggered by the Human Genome Project. Most human genes have a mouse equivalent. So to work out what a gene does, scientists breed "transgenic" mice with altered copies of the gene in question and study how they differ from normal mice.

The NIH's budget grew more 70%, after accounting for inflation, between 1997 and 2012, the period covered by the documents obtained by PETA, which probably also contributed to the increase in animals.

It's unclear whether the growth in the use of lab mice has been as large as PETA suggests, however. While the 25 institutions in PETA's study snare more than a quarter of NIH grants, they may not be typical of the more than 1,000 facilities that submit animal welfare assurances to the agency.

Megan Columbus, head of communications with the NIH Office of Extramural Research, told BuzzFeed News by email that some of the largest recipients of NIH grant funding run large "mouse resource centers," breeding transgenic and other mice to supply to scientists at other institutions. "The inclusion of resource center data will skew the data," she said.

But data from other countries suggests that the overall upward trend identified by PETA is correct.

In the U.K., where statistics on animal research have been collected since 1876, the total number of procedures involving lab animals increased by 52% between 1995 and 2013. This was overwhelmingly due to transgenic animals, mostly mice — if not for them, there would have been a decline of 16%.

Similar trends have been seen in other countries, Daniel Weary, an animal welfare scientist at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, told BuzzFeed News. In a 2009 study, Weary looked at animal use reported in more than 2,500 papers published by biomedical scientists from 24 countries in four leading scientific journals. The percentage of papers reporting animal use rose steadily from 1992 to 2007, after a decline in the 1980s. This was driven by a rise in the use of transgenic animals.

Weary is frustrated by the lack of good statistics from the U.S., which is assumed to use more research animals than any other nation. This means that anyone trying to document trends in animal research has to resort to laborious indirect methods. "How can you have an act that excludes the vast majority of animals that are actually being used? It is nonsensical," he told BuzzFeed News.

Getting mice and other excluded animals included in the statistics compiled by the USDA would require the AWA to be amended by Congress — which no one expects to happen any time soon.

The National Association for Biomedical Research, which advocates for institutions involved in animal research, argues that bringing excluded animals under the AWA would be prohibitively expensive, costing research labs up to $370 million per year.

"Those figures don't even account for the additional cost burden the USDA would have to bear," Matthew Bailey, NABR's executive vice president, told BuzzFeed News by email.

PETA this week sent a letter to the NIH urging it to start publishing the data it receives in institutions' animal welfare assurances, so that this can be used as a yardstick to judge whether policies intended to minimize the use of animals are actually succeeding.

That also seems unlikely to happen. Columbus, of the NIH, told BuzzFeed News that the average daily inventory is intended to give a "snapshot" of animals in a facility. Analyzing these figures to track trends in animal experiments would be "inappropriate," she added, as it does not accurately reflect the total numbers of animals used over time.