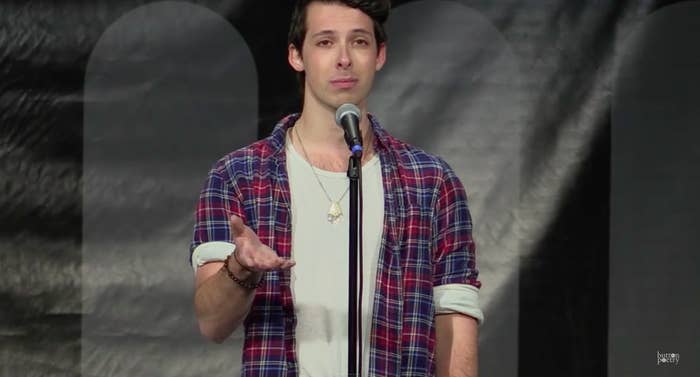

This is Kevin Kantor. He's a 22-year-old poet and acting student at the University of Northern Colorado.

One day last year, Kantor logged into Facebook and, as usual, got suggestions of "people you may know". Except this time, Facebook suggested he connect with the man he says raped him.

Kantor told BuzzFeed News that he was raped two years ago, when he was 20. The police asked him in the hospital afterwards why he didn't fight back. His brother asked him that too, he said.

Eventually, Kantor decided to fight back in the bravest way possible: on stage, in front of thousands.

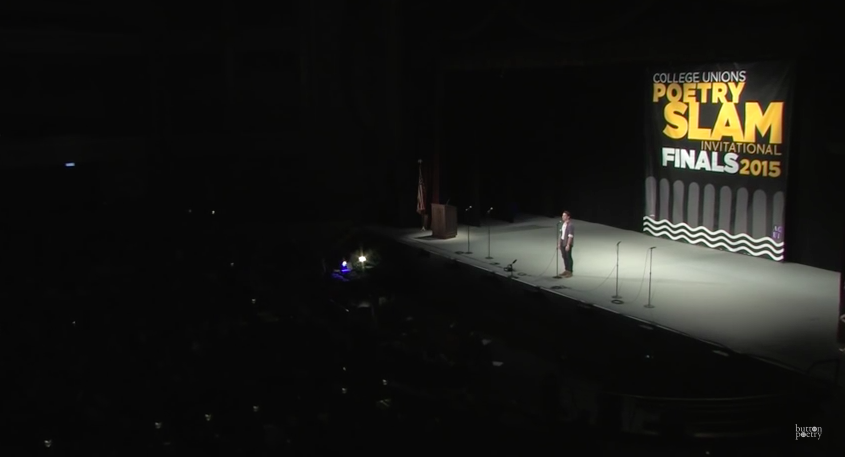

You can watch his performance here. It won him two awards at the 2015 College Unions Poetry Slam Invitational.

View this video on YouTube

In the poem, entitled "People You May Know", Kantor describes the moment he logged on and saw the man he says attacked him, before clicking on to the profile and discovering photos of him at the gym, dancing with his shirt off, having sushi with friends – and seeing how many people had liked them. He says he found pictures of the man as a baby.

The poem reveals what he learned from the profile: what the man listens to on Spotify, what his middle name is, and that they have three mutual friends. Then he talks about people's reactions – in particular, that "no one comes running for young boys who cry rape".

Finally, he describes how he copes with what happened: "Every day I write a poem titled 'Tomorrow'. It is a hand-written list of the people I know that love me, and I make sure that I put my own name at the top."

Kantor spoke to BuzzFeed News about the poem – and the events that led him to write it.

When did you log on to Facebook and see the man who raped you?

Kevin Kantor: That happened August or September last year.

What was your initial reaction?

KK: The first reaction was, "Is this real? Is this really him?" Then I clicked and went through it [the man's profile]. It was like an out-of-body experience, like I held my breath for five minutes. I felt paralysed. But I couldn't help myself but look through it because it felt… It was weird to think this person could go on existing, because I worked so hard to make him stop existing in my brain.

Have you considered sending him a message?

KK: No, I haven't. And I don't have any need, reason, or desire to. Since then I've blocked him on Facebook. The only thing I've ever really wondered is if he has seen the video, and if he has seen it, if he even realises he is who I am talking about.

When did the rape happen?

KK: When I was 20. It was an acquaintance I met through the gay community in the Boulder area. It happened when I was home in my spring break – at my brother's. I was downtown, and I had just gone to a poetry slam that night and then went out afterwards with him.

What happened afterwards?

KK: I had called a friend immediately afterward and he took me to the hospital without my really wanting to – now I'm thankful for it – but before I knew it I was talking to police officers who were asking me questions and saying they couldn't help me unless I helped them.

And all of a sudden I felt like I was pushed into a corner of silence – I was being given the space to speak, but only in a very structured way that wasn't right for me, which is why the first way I shared it so publicly was through a medium that makes sense to me, with a community that I know is receptive and listening.

So the way the police reacted shut you down?

KK: Absolutely. I was almost immediately asked why I didn't have any defence wounds, why I didn't fight back. And whether I was attacked, assaulted, or raped, and I had no idea how to answer that question. This was just hours after it had happened. I was put into a situation where [it felt like] there was a right or wrong answer and so I thought, I'm just not going to say anything.

Did the police investigation get anywhere?

KK: No. For a number of reasons, but really because of that first interaction – I was completely shut down. I know when I was there [in the hospital], doctors did exams and took some sort of tests, but to be perfectly honest I don't even remember what they were for, and I don't remember hearing back about anything. I was just given a lot of pamphlets and sent on my way.

The last interaction I had with law enforcement was just, "If you're not willing to help us, we're not going to help you." And I was like, "I don't feel like helping anyone right now."

Why was it important for you to describe your experience in a performance?

KK: Because for a very long time afterwards it was something that I would write about but not share – it was my coping mechanism – and eventually I realised that I was able to lend a voice to it and share my story in a way that I didn't know how to otherwise. When it happened, the feedback I was getting was, "This can't happen to male-identifying people." It was finally a way to take ownership of my experiences.

The rape of men remains pretty taboo – was there a political motivation too?

KK: Right, and when it comes to something like poetry often the most personal is the most political. I identify as queer and I find that whenever I write about the self in the most honest expression, it is a political statement as well because our life has been politicised.

The year that my attack happened I was the MC of our college's Take Back the Night event, which is a sexual-assault awareness event that happens on all college campuses. And even after all the training for that, after it happened I still felt the word "rape" didn't belong to me. I had trouble saying it, or when I said it it didn't fit right, because it was so ingrained that it wasn't something as a man I was supposed to talk about or admit to or succumb to.

What was it like to perform the poem?

KK: Even before I read the poem, I was incredibly nervous for how it was going to be received. And even while I was doing it, I was scared I was saying these words and taking ownership, and felt that putting myself out there was a risk. It was scary using those words for myself for the first time.

But the performance was one of the most liberating experiences I've had in my entire life, because there were a few thousand people in that theatre and afterwards, while incredibly overwhelming – it was only the second time I'd read that poem in public – a lot of people came up to me just hugging me and shaking my hand and saying very few words, just "thank you" or "I appreciate that". It was incredible.

Did you sense that some of those people understood from experience?

KK: In person not as much, but over the internet I've had a lot of feedback from countless people telling me the exact same thing happened to them – hundreds. It's been difficult but incredibly rewarding because a lot of people now feel safe enough to share their stories with me.

It has been a little bit jarring because I'm getting a lot of people sending me stories of their own personal trauma. It's something I understand, that when there's a video of me speaking so candidly about something so personal people feel the safety to express to that person their own story. It's about half and half men/women. And of all ages. Men who are younger than me and some in their fifties and sixties, expressing what they were quiet about for decades.

How did performing the poem to thousands compare to telling someone one-to-one?

KK: In a sense it was easier, specifically because of the fact I was doing it through the vehicle of poetry, which allows you the space to be vulnerable. It's given me the freedom and space to talk about it on a personal level, one-on-one with people that I did not have before. There's something about it being out there that has allowed me to talk about it more freely.

Now I know that people know and therefore I'm not holding the secret any more. I feel like now I share the weight with everyone, so it doesn't feel as weighted when I talk about it because it doesn't feel like I have to come out about it.

You mention your brother in the poem – how did he react to it?

KK: When he saw the video he texted me and more or less said, "I'm sorry I wasn't there for you when you needed me." And the fact is, he really was – he's never not been there for me. I realised that even the people that love you most don't know how to deal with trauma. He understood why it was important that he was part of the poem, because it wasn't only a police officer who asked me that [why he didn't fight back], it was the person who loved me most in my life.

What would you like to say to people who have been through similar things to you?

KK: Don't let other people deny or invalidate your experiences and your truths. Recognise the strength it takes to just survive afterwards in a culture that tells you that your experiences are invalid. The greater thing I've learned is it's not something I need to be ashamed about at all, and there's power in speaking out about it.

What has enabled you to cope?

KK: I had a really good network of support, people I felt safe with. I only told three or four people before the poem – people I really knew I could trust. Also, I was able to find incredible resources online and at my school to help me through.

How are you now, today?

KK: It's interesting because for a while it felt like something that was behind me but now it's so saturated – it's something I talk about daily because of the attention that the video's been getting. But in a good way. It's something that… I'm excited for my future now. For a while I wasn't. I didn't feel excited about tomorrow and now I am, every day.

BuzzFeed News approached the Denver Police Department, which declined to comment. Facebook did not immediately respond to requests from BuzzFeed News for comment.