Charlie Willis was dancing in a gay club with a man he had just met when the man tried to put his hands down Willis's trousers. "'What the hell are you doing?' I said. And he said, 'Can you even get an erection?'"

Willis, 24, laughs and then scoffs – a snort of derision. As a bisexual man with cerebral palsy – the cluster of neurologically induced movement disorders – Willis has developed a wealth of responses to crass ignorance. There was, for example, the man on Grindr who said, "You're way too hot to be disabled." To which Willis replied, "No, mate. I'm too hot to even talk to you."

A few days before National Coming Out Day, he has invited BuzzFeed News to his flat in Brighton to discuss the routine idiocy he faces from strangers, dates and even partners.

Another man on Grindr sent the following message: "Oh my god, I've never slept with a bisexual person before! That must be really exotic!" Willis rolls his eyes. "I was like, What the hell?! There's nothing about me or my identity that's exotic! There's nothing different about the way I sleep with people."

For Willis, attitudes towards both bisexuality and disability collide in such a way as to create a complex backdrop for coming out, sex and dating. "In day-to-day life," he says, "bisexuality is invisible, so one side of my identity is invisible – although often hyper-sexualised – and on the other side there is this very visible physical disability, but disabled people are desexualised."

Willis works at an organisation for people with disabilities, and walks with a stick. His particular version of cerebral palsy is called spastic diplegia, which affects the mobility of muscles in the legs and pathways between those muscles and the brain. It means that his gait is uneven. He sways a bit, he stoops a little, and this is progress.

"I used to move my top body a lot more and have my arms up in order to balance," he says. "It wasn't until I used my stick when I went to college that my arms went down to my side and I looked a bit more 'normal'." Willis remembers his first ever steps.

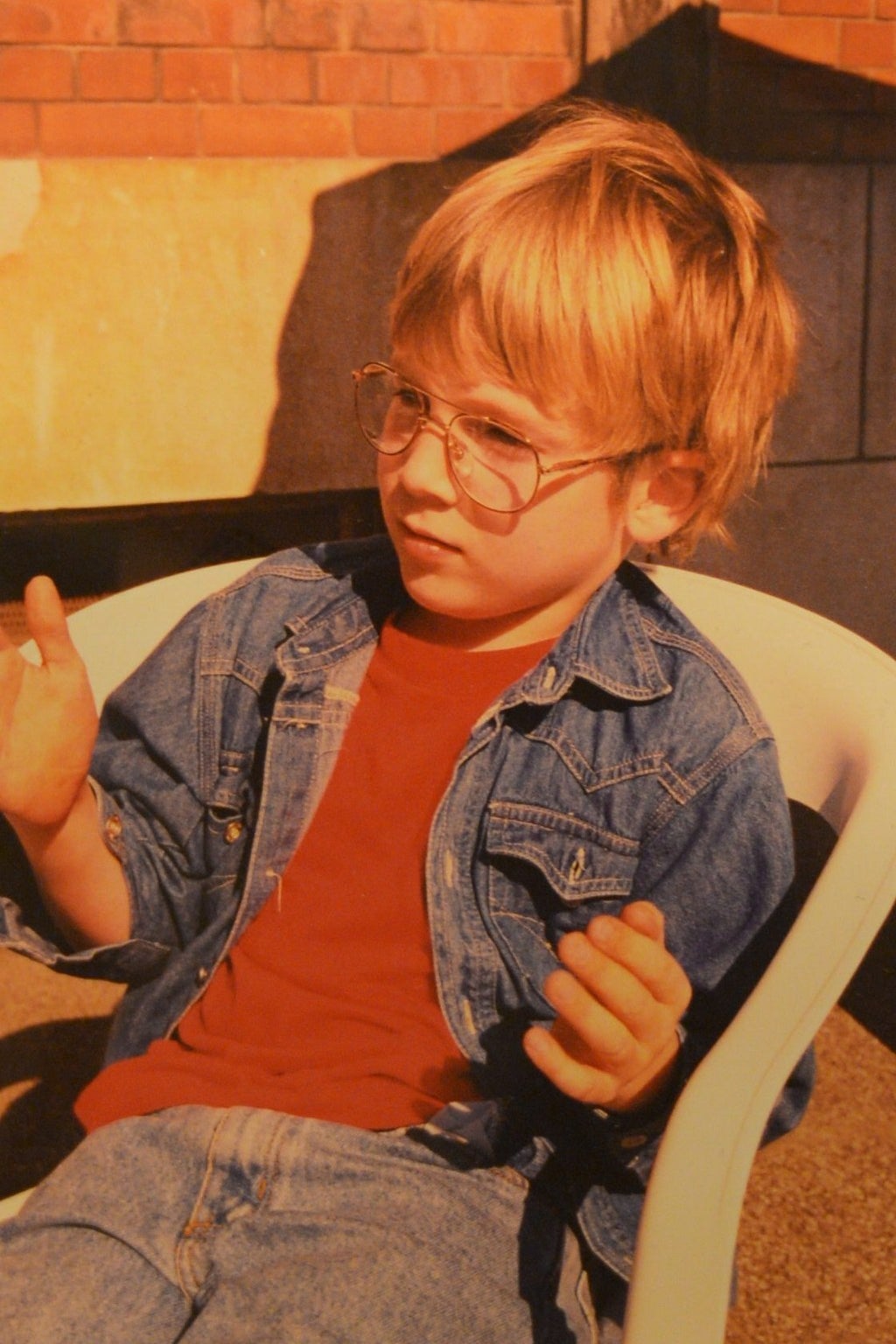

"I was 6 or 7," he says, looking up into a corner. Not long before, while Willis was at a mainstream school in Woking, Surrey, he had an operation on his hamstrings – little bows tied around the tendons to enable more movement and help him walk unaided.

"It was at the London boat show, in an office building. I thought, I think I can do this! and just did it. I took my first independent steps outside of my walking frame." He looked round and there was his father and his father's friend watching. "They were in tears."

For a short period in secondary school, Willis started using a wheelchair rather than the frame.

"My physiotherapist took me to one side and said, 'You can use this and your legs can deteriorate because of the lack of movement, or you can get back to using your walking frame.'" He took the doctor's advice.

By 15, Willis realised he was not straight. He started attending an LGBT youth group and embarked on a relationship with another guy. At 17, he felt able to talk about his sexuality.

"I came out first as bisexual and thought, No I'm probably, definitely gay, and then later thought, Hang on, no, the bisexual label fits. It fits a lot better than any other label." Willis told his mother the news. A couple of weeks later, he says, she was putting the laundry away and asked him, "'Charlie, do you think this is possibly a phase?'' And I said, 'No, mum,' and she replied, 'OK, fair enough.'" And that was that. "Personally, the experiences I've had coming out have been very positive," he says.

But preconceptions around bisexuality and disability pervade, and, says Willis, the gay scene is no less full of unhelpful attitudes.

"If you're disabled, people think it's their right to know how you're disabled, why, or how it happened: 'What's wrong with you?'" Bouncers, he says, ask his friends as they're entering a club, "Is your mate going to be alright?" Taxi drivers on the way home think he is drunk. Or, he says, grinning, "more drunk than I actually am".

Willis hasn't used only Grindr, but also sites like OkCupid. Whichever he uses, before meeting anyone, there is something he always does: comes out about having a disability.

"I've never had the courage not to say anything about my disability, even if it's 30 seconds before we meet, I'd send a message: 'Just so you know, I walk with a stick, I have a disability.' The reason I do that is because it puts it there: Here's my issue, deal with it or fuck off." He looks down. "I wish I didn't have to do that."

On dating apps, he says some people simply stop talking to him when he reveals he has a disability. Others carry on talking but seem to see only his disability.

"I met up with someone on Grindr and, oh my god, he spent a long time talking about how other members of his family are disabled, as if I was on tap to talk about disability all the time. I'm like, 'Um, great, I really don't care that your nan has bad hips!'"

The latest research from Scope, the disability charity, found only 5% of people without a disability have dated or even asked out someone with one. Its new campaign "End the Awkward" aims to encourage people to feel more comfortable socialising with and dating people with disabilities. As Willis talks, it seems Scope could extend its message.

"Previous partners of mine have been taken aside [by their friends] and asked, 'Are you sure you want to date this guy? He's disabled.'"

Willis has had long-term relationships with men and is currently in a relationship with a woman who he says is "much more supportive". A previous partner, he says, once told him, "I reckon you're probably gay or bisexual because of your disability." He scoffs again.

"The reason he said I wasn't straight was that women are less likely to want to sleep with men because they don't see me as a possible reproductive partner," he adds, laughing darkly. The same partner said Willis would never cheat on him because he has a disability.

"That was wrong," says Willis, his solemn expression giving way to a smirk, "because I did cheat on him."

Despite this passing flash of glee, the pain of these remarks colours Willis's present – with both sex and dating. He asked his current girlfriend, "Does it matter that I ask you to carry the pint when we're in the pub or that I ask you to pick something up for me? You don't feel like a carer?" He describes a recent night out at Legends, the Brighton gay club, when a circle of men formed around him and a friend, cruising them. But the idea of picking someone up in a club is alien for him: "If I didn't have to trust someone so much not to discard me because of my disability then I would have been freer with my sexuality."

Sometimes, he continues, he feels like "some kind of plaque on the wall to be achieved". Past relationships have often ended because of "some element of my disability". And that, he adds, is "really shit".

Which is to say nothing of the encounters Willis experiences outside of dating. Religious people have approached him in the street and said, "You're disabled because you're atoning for previous sins so you can be in heaven in the next [life]."

Even the more common, well-meaning attitudes can be exasperating.

"The very idea that I'm inspiring for being able to get on a bus or cook a meal is absolute bollocks," he says. "And the idea that disabled people have to be thankful for the treatment they received, regardless of if it's 'Please let me help you off the train' or 'You know there's a lift, right?' Attempts at caregiving. People are surprised when I'm agitated; they feel like I have to be nice to them. The fact I'm disabled doesn't mean I can't also be a fucking arsehole sometimes."

Wider acts of societal caregiving – the kind that is needed and wanted – however, are under threat, he says. He mentions cuts to benefits and social care for people with disabilities. He cites the struggle for some to survive. But there is something else that surfaces, something less obvious, less visible, and which entwines with sexuality.

"LGBT people spend a lot more time working on the acceptance of their own identities before they come out," he says. "Whereas less time and resources is put towards helping disabled people accept their identities. The spark of the LGBT movement was about 'Accept me for who I am'. More time needs to be given to letting disabled people do that too."

Everyone, he adds, is vulnerable – yet it is people with disabilities who are viewed in these terms, in a way that wraps them in cotton wool, without helping where it's really needed. The previous discussion about visibility and invisibility, the two facets of his identity fighting against opposing forces, returns. Willis leans forward, takes a sip of tea, and describes as if remembering all the thoughtless comments he's had, how it felt when the man asked if he could get an erection.

"It dehumanises me."