The abuse began almost immediately. Nigerian asylum-seeker Aderonke Apata had just arrived at Yarl's Wood detention centre in Bedfordshire when the other detainees spotted her.

"They were looking at me so strangely," she tells BuzzFeed News, "And I thought, 'What's going on here?' And then the homophobic attacks started. Verbal, physical..."

She stops for a moment.

"They would just walk up me and say, 'You look like a man. Are you a boy?' People from my country were the worst, because they were more religious."

Yarl's Wood is an "immigration removal centre" where people, mostly women, are detained while their asylum claim is assessed. What makes it, and all such facilities in Britain, different from anywhere else in Europe is that there is no time limit on a stay. Detainees can be kept there for years.

Apata, 47, left Nigeria in 2004. Police back home had, she has said, arrested and tortured her. Her partner had been murdered because of her sexuality. And a Sharia court imposed a death sentence on Apata: stoning. She fled for her life. In the first week of December 2011 she was taken from prison to Yarl's Wood, with no idea how long she would be kept there.

Her first impression, she says, was that "there was no difference from prison – so many doors, so many keys, so many gates". But that was just the building.

The Nigerian words (in the Yoruba language) used to attack lesbian and gay people, says Apata, "translate into 'witchcraft'". So fellow detainees called her "àjë": witch.

She says another word was deployed regularly: "esu". It means devil.

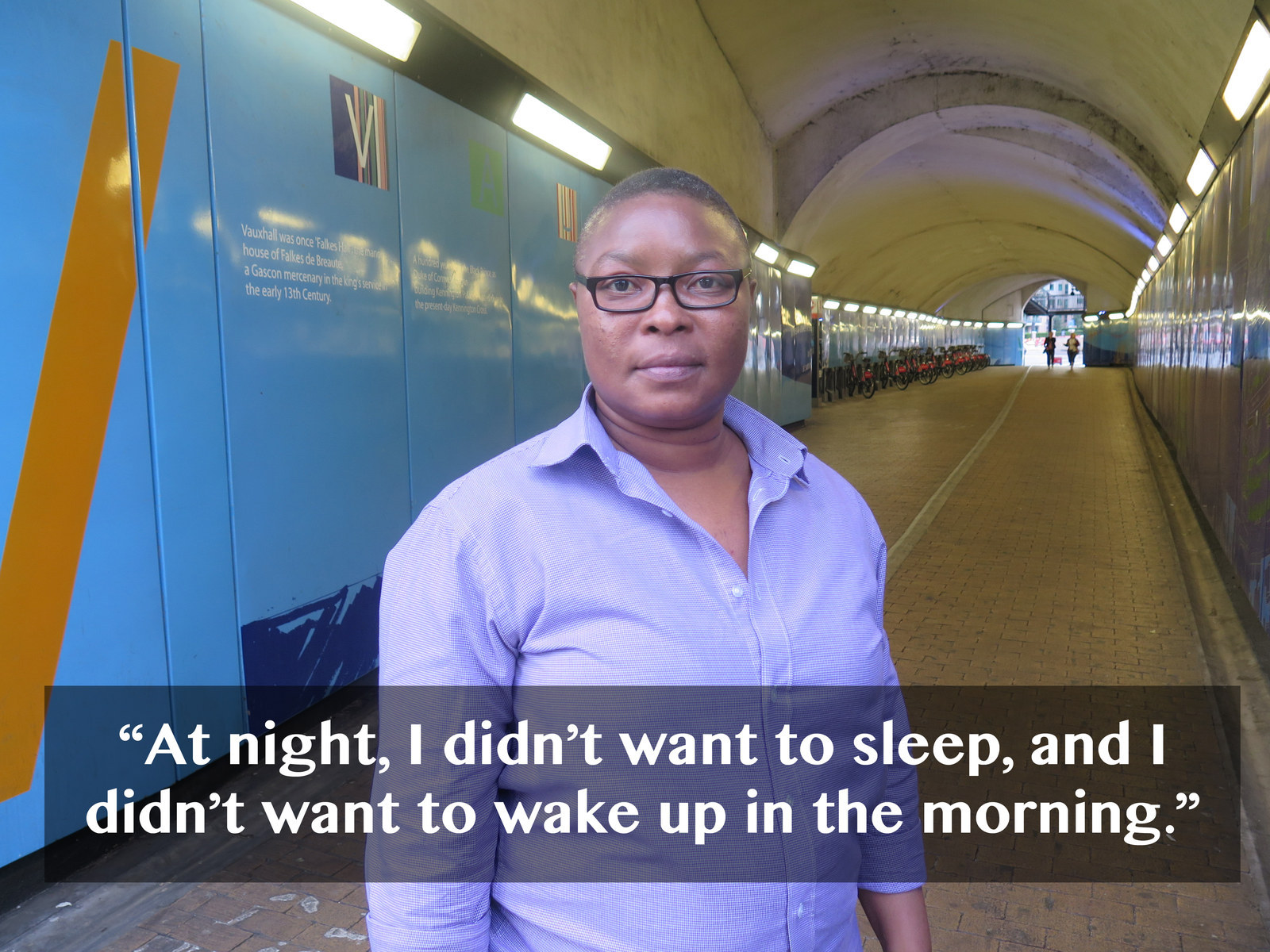

"I was called that every day," says Apata, looking straight ahead, her alto voice flat, matter of fact. We sit on a bench in a south London street as the stories about her time in Yarl's Wood trickle out.

As a practising Christian, Apata would go to the detention centre's chapel as often as possible. Sometimes a chaplain would come to take services, but mostly the detainees would conduct them themselves, on a rota system.

"One day it was my turn," says Apata. "But another detainee who called herself a pastor pushed me over and said, 'The pulpit isn't meant for homosexuals.' She said she was sent to Yarl's Wood by God to come and clean it of filthy things like homosexuality." The woman vowed to turn Apata over to the Nigerian government if Apata was deported.

This was far from the only threat Apata faced. She eventually found some other lesbian detainees in the centre and befriended them.

"But because I was with them they also started being attacked. We were not even safe together. Every day, constantly, we were being subjected to psychological, emotional, and physical abuse. You would have somebody threatening to beat you up. You would just have to walk away."

Amid the hostility, Apata started staying in her room as much as possible.

"If I went out I needed to ask an officer to go with me." But it wasn't only the practical problems that affected her daily life.

"My confidence was gone. I didn't have any self-esteem. At night I didn't want to sleep, and I didn't want to wake up in the morning." Staying in her room didn't always keep her safe, either, she says.

On one occasion a fellow detainee entered without permission, she says.

"She came to attack me; she was talking at the top of her voice, trying to start a fight, but I just kept quiet, I didn't say a single word, which made her uncomfortable. After a while she just walked out." Apata reported such incidences, and "some" were investigated. But the abuse, she says, and the resulting sense of terror, never stopped.

"It was constant psychological torture," she says. "When I was in prison I knew when my sentence was ending, but in the detention centre I didn't know when I was going to be released or whether I would be deported."

She remained there for nearly a year. But Apata hasn't been granted asylum. In April this year, the High Court rejected her claim. The judge, John Bowers QC, said he agreed with the first tribunal that "she has engaged in same-sex relationships in detention in order to fabricate an asylum claim based on claimed lesbian sexuality".

During the case, Apata submitted an array of materials as evidence of her sexual orientation, including a DVD and photographs depicting her having sex with her partner. The Home Office's barrister, Andrew Bird, argued she could not be a lesbian because she has children. "You can't be a heterosexual one day and a lesbian the next day," said Bird.

Apata can be taken back to the detention centre at any moment. What does that feel like?

She looks straight ahead again.

"There is no day... In fact, when I close my eyes is the only time when I don't think about my immigration problem. Not just if it's going to be granted, but whether I'm going to be detained. It's constantly in my head." When she tries to avoid thinking about it, and about her time in Yarl's Wood, it comes to her at night.

"I suddenly wake up, sweating, with nightmares."

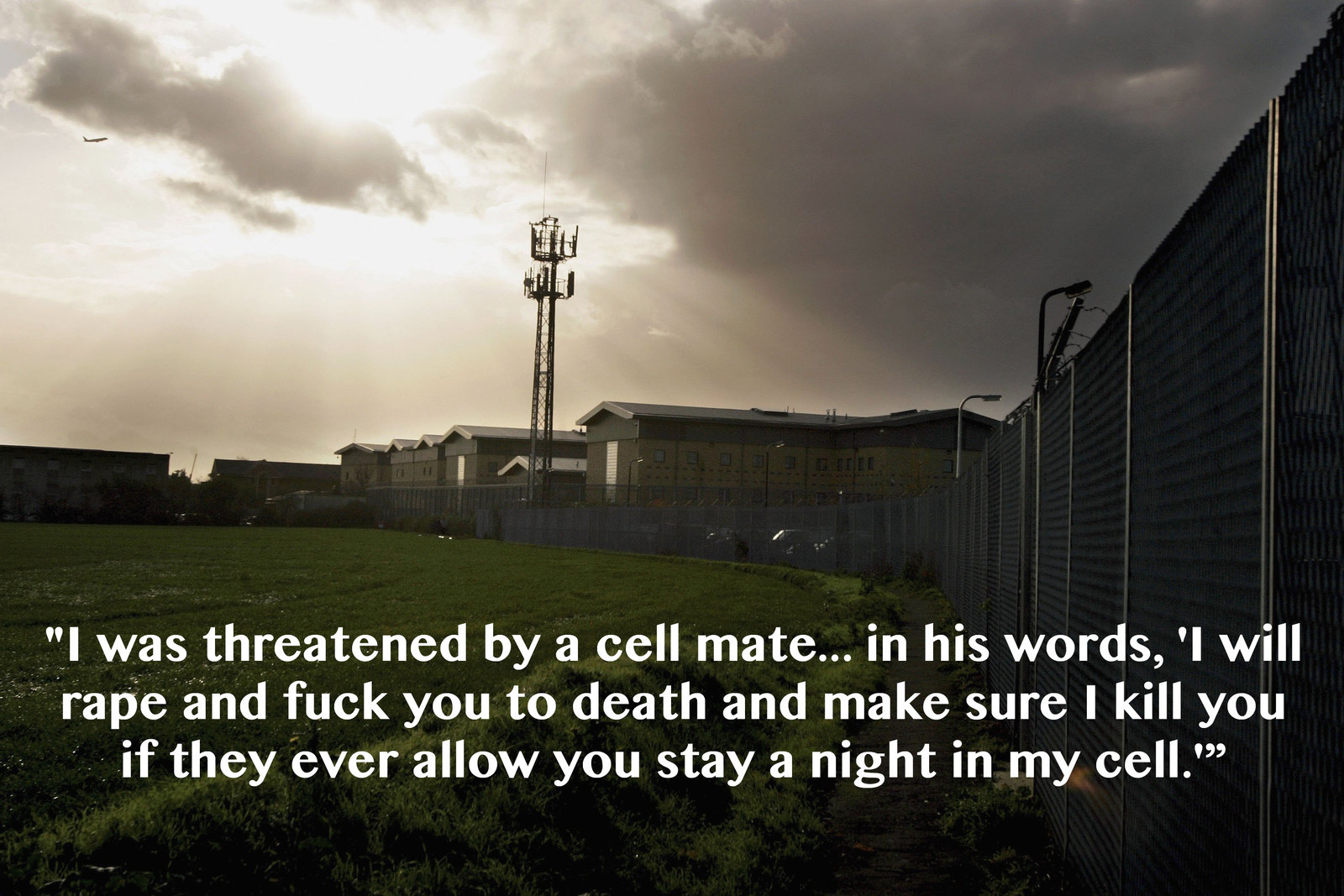

A protest by G8 Alternatives outside Dungavel Dentention Centre

If deported, her fate looks bleak. Lesbians and gay men can be jailed for 14 years in Nigeria. Last year, a new law was introduced; now, anyone who does not report someone for being gay can be jailed for 10 years. Violent homophobic hate crimes have risen.

The most recent research available suggests 1,200–1,800 lesbian, gay, and bisexual people claim asylum in Britain each year, although it is impossible to verify figures as the Home Office doesn't publish them. Women for Refugee Women estimates that around 340 lesbians were locked up in detention centres last year.

For nearly a decade, concerns have been raised about the treatment of LGBT asylum-seekers, including abuses within detention facilities. A 2014 investigation into LGBT asylum claims in Britain by John Vine, the independent chief inspector of Borders and Immigration, found that a fifth of asylum interviews still feature stereotyping and over a 10th contain questions "likely to elicit sexually explicit responses".

And in a recent submission to the Shaw Investigation (the Home Office's review of detainees' welfare in immigration detention centres), the UK Lesbian and Gay Immigration Group (UKLGIG), said it has "serious concerns as to the quality of asylum decision-making … and serious concerns have been expressed as to the experiences of LGBTI people in immigration detention. LGBT detainees frequently experience social isolation, physical and sexual violence and harassment by both facility staff and other detainees. Trans people are particularly at risk."

For gay men in detention centres, some of the abuse takes a markedly different form to that experienced by Apata.

Karim – he asked BuzzFeed News to use a pseudonym for his protection - came to Britain from Pakistan in 2006 to study. The 29-year-old is, he says, "very girly" by nature, although not transgender.

"I belong to a very strict Muslim family," he tells BuzzFeed News. "They knew about my sexuality but they thought as I grew up I would get married and everything would be fine." While in Britain, Karim's family came to realise this was unlikely. They said that if he didn't change he would not be welcome in the family.

"My elder brother used to send me emails saying, 'You're a sinner, you'll get HIV as a punishment from God, and if you don't get HIV I will kill you because you [bring] shame on the family and shame on being a Muslim.'"

Karim was terrified.

"And the law in Pakistan can't save me because they have Sharia law."

Old colonial laws in the country remain, allowing for imprisonment of 10 years for same-sex activity and a life sentence for sodomy. But in some cases, Islamic laws can combine with colonial ones, and other punishments can be ordered: whipping of up to 100 lashes, or death by stoning.

After applying for asylum and being homeless for two years, sleeping on friends' sofas, Karim was taken to Harmondsworth detention centre, near Heathrow, in early 2014. It is the largest in Europe.

"The very first day, at check-in, I was wearing bangles and the officer said to me, 'Take off your bangles,' and laughed. He started checking my bag and when he found lipstick, foundation and an eyebrow pencil he was showing it to another officer and to everyone, saying, 'Oh, this is a nice thing!' to humiliate me. There was so many other people behind me and he was showing everyone and laughing and laughing."

Soon after arriving in his room, Karim realised what the nature of the abuse would be.

"Whenever I walked through the corridors, when I went for my lunch or dinner, they [other detainees] all stood in the corridor, touching their cocks and their balls and saying, 'Suck my cock.'" On many occasions the harassment moved beyond the verbal, he says.

"They touch your bum, your cheeks, they would grab my hand and try to put it toward their cock." Karim would have to push their hands away and run back to his room.

"It was the most horrible experience of my life," he says, "People just saw you as a sex toy. They [detainees] are kept inside, many for more than six months, and are desperate to have sex with anyone. I was an easy target." And, he adds, one of his two gay friends in Harmondsworth wasn't able to prevent the harassment escalating further.

"He lived on the second floor," says Karim. "He went to his room and another detainee came in his room, pushed him and locked the door, pulled his trousers down, and said, 'Suck my cock.' My friend was crying and said, 'Get out.'" The man, says Karim, orally raped his friend.

Afterwards, Karim took him to the staff on duty.

"The officer said, 'Do you really want to report it? You'll have to face the medical team and your [asylum] claim will take more time.' It was kind of threatening. So we said no, we don't want to."

But Karim did report sexual harassment as well as verbal abuse. The other detainees, he says, would regularly call him a "cocksucker" and other homophobic slurs. The response from staff was not what he was hoping for.

"They [officers] said, 'You are very visible, you have to hide yourself.' I said, 'What do you mean? I’m not wearing any make-up or high heels or skinny jeans. I’m living like a prisoner inside and you’re asking me to tone myself down? How can I?'"

After nearly a month, Karim was released and granted refugee status. He suffered depression as a result of his time in detention, and he says, "I still struggle but I'm more confident. I don't want to hide. I'm proud to be openly gay."

His experiences, along with Apata's, mirror many described in UKLGIG's submission to the Home Office. It quotes some of its clients and some interviewed for other pieces of research. One detainee, in 2013, reported:

"I was threatened by a cell mate. After calling me all manner of derogatory remarks, in his words, 'I will rape and fuck you to death and make sure I kill you if they ever allow you stay a night in my cell.' It all happened in front of a prison official."

UKLGIG notes in its submission that after chief inspector Vine's report was published the Home Office "proposed an 'Action Plan' on LGBTI claims to ensure effective reform in December 2014", adding, "On 16 March 2015, the Home Office apologised and confirmed no action had been taken in respect of the Action Plan."

What both Karim and Apata are able to do is describe what happened in detention centres. Although distressing, they can revisit what they experienced. This is not the case with the poet and activist P.J. Samuels when BuzzFeed News sits down with her outside a London pub.

After leaving Jamaica – she refers generally to being hurt there, having to move from one place to another, every relationship she had with another woman being subject to persecution – she sought asylum in Britain. And like Apata, Samuels was taken to Yarl's Wood. It was 2010.

Even in the van on the way there, she says, a fellow Jamaican woman made her feel unsafe.

"She was expressing her distain for LGBT people, how wrong she thinks it is," says Samuels. "It automatically locks into the fear I already have of being hurt, and having been hurt over time. If people say [homosexuality] is wrong and disgusting, it is enough to traumatise you."

Having never been in trouble with police, being searched and then incarcerated in the centre was further traumatising for Samuels.

"I went into survival mode. There was a lot of disassociation I had to do that I didn't realise I was doing until the process hit me afterwards."

She looks away.

"I had a huge mental fallout afterwards," she says. "I kept a diary the whole time and I still have not been able to read it. I've had therapy and I'm still not prepared to revisit those experiences in that direct kind of way."

And so, instead, she talks about some of the other people in Yarl's Wood.

"I had to go to the authorities to ask for one young lady to be moved to a different room. She was Jamaican, and so was her roommate who would say, 'I don't like them people, don't put no gay people inside here.' It was constant. And the woman she was sharing with didn't have the voice to say to somebody what was happening. She would stay up all night because she did not feel safe enough to sleep. During the day she would come over to my room to have a kip."

Samuels says there was a "hanging sense of threat" in the centre for gay people like her.

"The [homophobic] hostility is palpable," she says, with detainees regularly voicing their disgust about homosexuality and telling LGBT people "what you shouldn't be doing with your life."

As a result, she went back in the closet, compounding the problems she had already experienced coming to terms with her sexuality in Jamaica.

"There was a part of me that bought into the notion that who I was was wrong," says Samuels, adding that being in a detention centre was even worse than being in Jamaica.

"They affect you in different ways because in Jamaica as a lesbian I was a complete person and being a lesbian was a small part of who I was that was challenging, as it impacted my survival. In the UK I was non-existent – the only part of me that mattered was the fact that I was a lesbian and it was being hung up in an arena that had already assumed I was lying and locked me up."

She takes a breath.

"If I had known how challenging it would be psychologically to claim asylum I wouldn't have. And all the people I am close to that are now refugees, we have all said, given what you go through, we wouldn't have claimed asylum. You have done nothing you would consider criminal but they strip your rights, your voice, your person."

UKLGIG, in its report, notes that it has "raised serious concerns about the bullying, harassment and abuse of LGBTI people in immigration detention centres with the Immigration Minister, James Brokenshire MP, the Home Office Permanent Secretary, Mark Sedwill, the Director-General of UK Visas and Immigration, Sarah Rapson and other senior civil servants. The Home Office has yet to propose steps to tackle this issue."

A Home Office spokesperson told BuzzFeed News: "Detention and removal are essential elements of an effective immigration system and we take our responsibilities towards detainees' welfare extremely seriously. That is why the home secretary has commissioned an independent review of detainees' welfare to be conducted by the former prisons ombudsman Stephen Shaw. This is expected to be completed in the autumn."

Norman Abusin, from Serco, the company that runs Yarl’s Wood, told BuzzFeed News: “There have been no complaints from detainees about homophobic discrimination by other detainees over the past 18 months. We work hard to ensure that all residents are treated with respect irrespective of their sexual orientation and all complaints are independently investigated and action taken where appropriate.”

Samuels was granted asylum in September 2010, following her appeal to have an initial denial of her claim overturned. After everything she went through, and as if to echo scores of LGBT asylum-seekers in British detention centres, she says she is still a long way from coming to terms with what happened in Yarl's Wood.

Leaning forward, Samuels adds, quietly, "You don't get over that."

Mitie, the company that runs Harmondsworth detention centre, did not respond to requests for comment by BuzzFeed News.