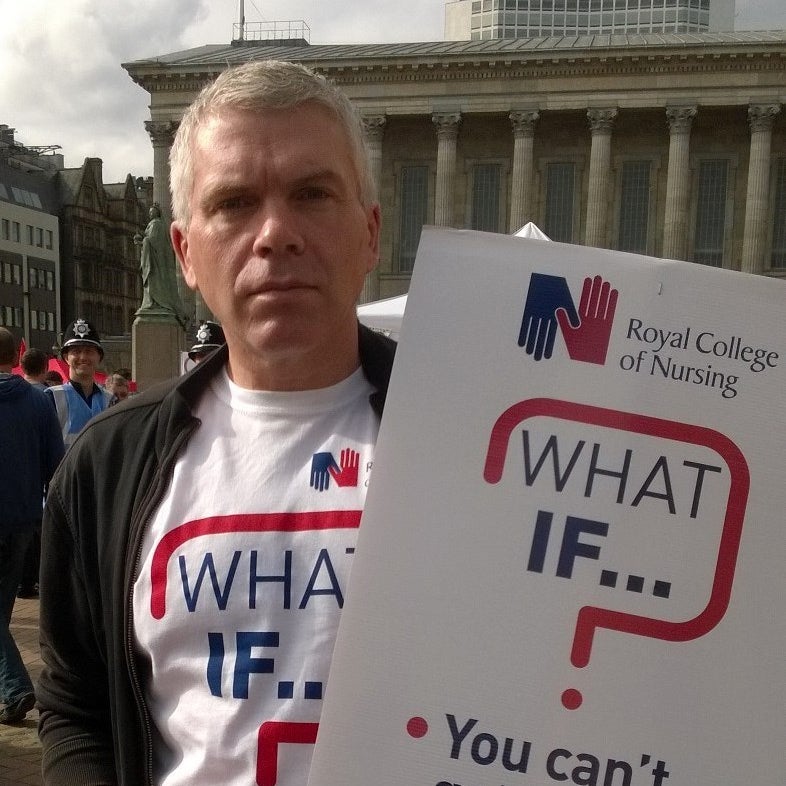

This is David Kirwan, the Green party candidate for Broxtowe in Nottinghamshire.

In 1998, he was diagnosed as HIV positive – and was almost immediately told that he had AIDS.

He is the first election candidate to go public about an AIDS diagnosis, and only the third to reveal he is HIV positive. The first and second were Adrian Hyyrylainen-Trett and Paul Childs of the Liberal Democrats, who recently disclosed their status in separate interviews with BuzzFeed News.

Kirwan, 47, told BuzzFeed News he was speaking out in an attempt to end the "secrecy and stigma" surrounding the condition.

At the time of his diagnosis, Kirwan was living in Brighton, and found himself becoming increasingly unwell.

"I was becoming so tired I could hardly walk to the end of the street," he said. "My throat was raw, I had all these ulcers that wouldn't go away. I kept going back to the GP and eventually he said, 'We've tried everything else, can we test for HIV?' I said, 'Fine.' It never occurred to me it might be positive."

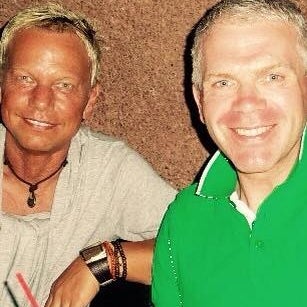

Kirwan had been in a relationship with his partner, Gary Kirwan, since 1987. But a week after the test he was back in the waiting room at the GP's surgery.

"I saw the doctor talking to a member of the reception staff. He said, 'Have you got that positive HIV result?' It was obvious it was me."

"It was surreal. I thought, 'It can't really be true.'''

"But when I went in he said, 'We've had the results and it does show antibodies.' There was no, 'How do you feel about that?' He just said, 'I know very little about this,' and gave me a number for the local STD clinic."

Kirwan went into shock. He spent two hours driving round Brighton before going home to tell his partner. But everything was about to get even worse.

The next day, Kirwan, who at the time was a support worker in the NHS, went to the sexual health clinic. Doctors there ran further blood tests to measure his CD4 count, which is the chief measure of the immune system's wellbeing. A healthy person's CD4 count is between 400 and 1,600.

"The next morning they rang me and said: 'We need you to come back today. We need to start you on treatment as soon as possible.'" His CD4 count was 7. Anything under 200 leaves the patient at risk of an array of serious and life-threatening infections.

"They said, 'This is an AIDS diagnosis; it's not just HIV.'"

Kirwan's consultant put him on antiretroviral medication immediately, which caused vomiting. But this side effect was quickly overshadowed.

"Because my immune system was in such a poor state by the time I started taking the pills, it triggered a reaction where my immune system start to fight everything in my body," said Kirwan. "It kickstarted this bug called MAI."

Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (or MAI) is an extremely rare bacterial infection that can affect people with compromised immune systems, typically in advanced cases of tuberculosis or HIV/AIDS.

"This became a far more important issue than the HIV," he said. "I was admitted to hospital because it was causing abscesses inside and outside my chest. When they x-rayed me they found 38 abscesses in my chest and on the surface of my neck. It was incredibly painful."

Kirwan's was only the 19th known case of MAI worldwide – but fortunately, two of those cases had been patients of his HIV consultant. Every day for several months, he went to the hospital to receive intravenous antibiotics. But the treatment didn't work. The abscesses were getting bigger.

"Eventually I got admitted," said Kirwan. He was put in a special clinic for people with HIV/AIDS. "There was a guy who'd been admitted the same day as me in similar circumstances – he'd been diagnosed a week before." That other man died in his first night in the unit.

"Gary came in to see me and that's when we thought, 'This is it, sooner or later it's going to happen.' My doctor tells me now that he never expected me to live."

With none of the treatment working, there was one last hope.

"My consultant said, 'There is something we could try, using a concoction of drugs, but it's quite dangerous,'" said Kirwan. "'It has a major impact on your heart, which starts to beat really quickly, and there's quite a big chance of heart failure.'

"But there was no choice. The alternative was I was definitely going to die."

He was attached to heart monitors and the drugs were injected into his veins.

"That was the most scary part – I could feel my heart getting really bad. Various alarms would go off and they'd have to stop the medication, wait for the heart to calm down, before starting up again."

It worked. After nearly two years in hospital Kirwan was finally allowed to go home – but the emotional impact of being confined to an HIV/AIDS unit for that long was profound.

"I made friends with people who'd been in there a long time," he said. "They all died. There was a guy I knew really well because we had adjoining rooms, and when I was transferred to the main hospital for the drug treatment, he died. I started to think, 'It's going to be my turn next. I should be gone.' I was skeletal at the time. I looked atrocious, shuffling around. My family were shocked when they would come to see me."

Despite other complications – such as the HIV medication causing pancreatitis – Kirwan recovered, and a year after being released from hospital he was able to go back to work.

His CD4 count has never fully recovered: He told BuzzFeed News it "hovers around 350". But he has resumed a normal life, working full-time as a senior trade union officer for the Royal College of Nursing. And in 2008 he and Gary – who has remained HIV-negative – had a civil partnership.

By that time, the couple had moved back to Nottinghamshire, where they grew up, but Kirwan still goes to Brighton for routine check-ups with the consultant who saved his life.

"There aren't the same sort of services in Nottingham," he explained. "And there's still a specific HIV/AIDS ward in the hospital in Brighton, with a range of consultants."

But it isn't just the medical aspect of the condition that prompted Kirwan to disclose his HIV status publicly.

"I wanted to speak out because there's still so much secrecy and stigma associated with HIV," he said.

"If I had diabetes there wouldn't be any reluctance to be open and people would be sympathetic, but you don't get that from people about HIV. People try not to look shocked [when you tell them], but you can tell they are – you can see it in people's eyes. We need to remove that and allow people to think it's nothing to be scared of."

Kirwan points out that his kind of suffering occurs only when diagnosis comes late. He believes he contracted the virus at least eight years before he was diagnosed. Today, Britain's first home HIV testing kit is going on the market.

"It will increase early detection," he told BuzzFeed News. "But I'm in two minds about whether that's a diagnosis you should get at home without any support or knowledge. People might get freaked out. Ideally people should go to an STI clinic where you can get support as well."

Kirwan is also concerned about funding cuts for HIV.

"We've seen significant cuts in HIV prevention funding," he said. "And it's really short-sighted because if we cut back on education and prevention, we're going to get an increase in diagnoses, which is then going to cost far more in treatment.

"It perpetuates this myth that HIV has gone away and is nothing to worry about any more. We're already seeing an increase in young gay men who think it's no big deal and you can just take a pill.

"Those pills can have a long-term effect and the condition itself can have a long-term effect. You may not be as ill as someone 30 years ago but it will have a big impact on your life."