Urgent action is needed to put an end to the "systematic abuse" of indefinitely detaining children with autism and/or learning disabilities under the Mental Health Act in hospitals often many miles away from their families and without access to proper treatment, according to a wide range of parents, campaigners, and politicians.

Last week BuzzFeed News covered the plight of Matthew Garnett, a 15-year-old who's been detained under the act in a psychiatric intensive care unit since September last year and whose family are campaigning for him to be moved to a clinical care placement where he can receive the assessment and treatment he needs.

But Matthew is just one of many children and young people who have been locked away in temporary treatment centres with no immediate prospect of release, sometimes for years, as a bureaucratic quagmire and a chronic lack of appropriate housing and care arrangements across the UK prevents them from being released and allowed to live nearer to their families.

Overall, an estimated 3,500 people with learning disabilities are being kept in inpatient beds in England, and many are children – although the exact figure for this is unknown. NHS England says that on average it costs £175,000 a year for each learning disability inpatient, costing the NHS £600 million a year in total.

BuzzFeed News has heard from parents of children and young people who have been detained for more than three years, sometimes hundreds of miles from home, while their parents are forced to battle endless NHS bureaucracy in order to get them back in their communities.

Some parents told us their children have suffered physical abuse while in a temporary assessment unit – while others alleged inappropriate treatment, excess medication, and a lack of understand of autism and learning disabilities.

Meanwhile, political pressure is growing on the government and the NHS to make sure children are not detained against their wishes and those of their families.

Sir Stephen Bubb, CEO of voluntary services body ACEVO, which last month released the second of two landmark reports into the provision of services for people with learning disabilities and autism, told BuzzFeed News that the long-term detention of children under the Mental Health Act is nothing less than "systematic abuse".

The reports were commissioned after the Winterbourne View scandal in 2011, when undercover journalists filmed staff abusing patients at a private hospital for people with learning disabilities.

"It’s not just the system, it’s the culture – society doesn’t like to think about people with learning disabilities," he said. "But they’re one of the most vulnerable communities in the country and they suffer systematic abuse.

"It’s not so much the abuse that we saw in the Panorama documentary on Winterbourne View, it’s the abuse where people are kept in situ for years, away from their family – they are overmedicated, they are often put in seclusion, and they are often subject to restraint, which leads to serious injury."

Luciana Berger MP, Labour's shadow health minister, called on the government to "take urgent steps to deliver the transformation in our learning disability services that is long overdue and desperately needed".

She told BuzzFeed News "too many people with learning disabilities are still living in inadequately staffed and inappropriate institutions when they would be better cared for in the community".

"These are some of the most vulnerable people that our NHS sees," she said, "but evidence shows that time and time again they are being let down. It is all the more worrying that it is often left to the families of patients to battle for the right support that their loved one needs.

"Just because some individuals have less ability to communicate concerns about their care must never mean that any less attention is paid to their treatment and care."

Norman Lamb MP, the former Liberal Democrat mental health minister who fought to secure the £1.25 billion in extra funding for children and young people's mental health services announced in January, told BuzzFeed News the detention of children for long periods using the Mental Health Act was "tragic and unacceptable".

"If you’re on the [autistic] spectrum it can be very traumatic for you to be in a completely alien environment," he said, "so the constraints on you are then tightened and your liberties are restricted even more, so you become more anxious and stressed. It’s an awful downward spiral.

"I think this is a big moral challenge. Whilst I understand there are cases where there are acute complexities, there are nonetheless lots of cases where it is absolutely not necessary to detain people in these conditions."

NHS England has committed to closing between 35% and 50% of all learning disability inpatient beds by 2019 and replacing them with alternative care in the community. But the families of children caught up in the system are calling for action now.

Since last week, Matthew Garnett's parents, Isabelle and Robin, have continued their campaign to get their son out of a temporary psychiatric assessment unit in Woking, and made several TV and radio appearances, including ITV's This Morning. The family's petition has now passed 300,000 signatures.

Also this week, Mark Lever, the CEO of the National Autistic Society, wrote to mental health minister Alistair Burt to intervene in Matthew's case – and on Tuesday the Garnetts will meet him to discuss their options, in a meeting brokered by their local MP, Helen Hayes.

And since the Garnetts' story exploded across the news media, other families have told of how their children have been locked in a cycle of detention and mistreatment.

Will Perks, 14, has atypical autism and ADHD and suffers from anxiety. All he wants is to go home for good.

After he was transferred from a specialist school to a mainstream one, he was targeted by bullies and became depressed. Eventually he began refusing to go to school. To make things worse, in October 2015 another boy punched him in the face at a local skate park after taking offence at something he'd said. Will is sociable but can come across as childish – his mum says he acts a bit like an 8-year-old.

After this, struggling to cope with the stress, he swallowed some pills in an incident his family feared could have been a fatal overdose.

Although it was not an overdose, doctors sectioned him for his own safety. There were no beds near his family's home in Bristol, so he was sent to a ward in Bury, Greater Manchester, where he ended up staying for three months.

In December Will was put back into an inpatient wing in Bristol. But he escaped, hoping to find his way back home to see his mum.

Police found him, and when they tried to detain him, he became distressed and kicked an officer. They arrested him and placed him in a regular police cell for 28 hours, just before Christmas.

He was sectioned again and sent to a psychiatric intensive care unit in Woking run by Cygnet Healthcare – the same unit where Matthew Garnett is being detained.

Will's stay in Woking has not been a happy one. His mum, Lorna Perks, told BuzzFeed News: "When he was in Bury the communication from the staff was amazing. In Woking there’s a lack of communication, they get his meds wrong. I had to report them because someone threatened him and said, ‘If you don’t stop it I’m going to punch your effing face in.'

"Another member of staff was restraining him and pulled his hand right back and hurt him. Both of which I complained about and both of which have been sorted. Both members of staff admitted it. It went through all the right procedures for safeguarding and the hospital was just saying, ‘It’s not unusual I’m afraid for this industry.'

"The staff at the hospital say they don’t want Will there – he’s on a ward with people with very serious mental health problems, including serious self-harmers, and he’s witnessing all that. He shouldn’t be there."

Fortunately, Perks is a woman who doesn't take no for an answer.

On one occasion when Will was younger, frustrated with the lack of progress she was having in getting him some acute care, she arrived unannounced at an NHS England office and told the receptionist that she wasn't leaving until she had been seen by someone. Just 10 minutes later, she had been seen and two hours later Will had been admitted to hospital.

"People have to look at children at a much younger age to identify if they have any learning needs," she said. "What happens is you’re just left to your own devices, and mainstream schools say they can handle it, but they can’t.

"The thing is, I’m a fighter and I will not wait for people. I’ve been fighting the system since he was 2 and a half, shouting very loudly."

On Friday 11 March she'll be at a meeting with health, education, and social care officials, discussing how to get Will's situation. Perks hopes for a care arrangement that will bring Will home, with some outside support.

And Will's sectioning was recently lifted, meaning he now spends a few days a week at home with his mum. He remains at the Woking unit the rest of the week as an informal patient until a permanent place for him near his family can be found. Perks says her son has become so institutionalised he refuses to go outside.

Cygnet Healthcare said in a statement in response to the allegations of abuse: "In both instances we carried out thorough investigations and notified the local authority safeguarding team, who confirmed they were satisfied with the outcomes of each investigation. Due to the need to respect patient confidentiality we are not able to comment in more detail.

"The health and wellbeing of patients is our absolute priority. A Psychiatric Intensive Care Unit is an emergency admission ward where patients who are very unwell are assessed and treated, and then may be moved on to specialist placement or back into the community, dependent on their individual needs. It is not equivalent to an A&E Department. If a concern is raised we carry out a full investigation and, where appropriate, liaise with the relevant authorities."

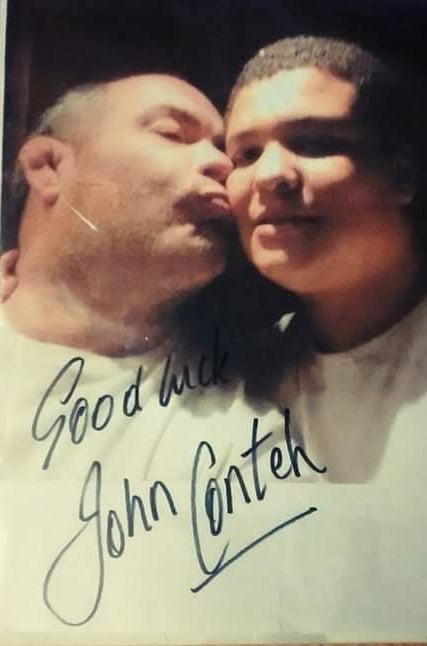

Stephen Andrade-Martinez, 21, from Islington in north London, has spent three years and two months away from his family after being sectioned under the act.

For the last year he's been at a specialist autism ward at a hospital in Colchester, Essex, a two-hour drive from their home in Islington, north London. Prior to that he spent two years at St Andrew's in Northampton.

There is no realistic immediate prospect of Stephen being allowed to live back in the community – one housing officer told his family it could be another two years before something appropriate is found nearby.

By that point he will be 23. When the process of finding somewhere for Stephen to live that could meet his needs began, after his residential school said it couldn't cope with his behaviour, he was just 16.

His mum, Leonor Andrade-Martinez, says her son, once a bright and sociable boy with an infectious sense of humour who rode horses at a specialist school in Norfolk, is now unrecognisable from the child he once was.

Stephen has been admitted to hospital twice a week for the last six weeks, she says, because he is self-harming so much. He did this before being institutionalised, she says, but not to such extremes.

She described the moment she first saw him in St Andrew's, after he'd been there one month: "As soon as we saw him it was like a knife going through my heart. Stephen was no longer our Stephen. He looked absolutely awful, just horrendous. I could see the amount of weight he had lost. He was so drowsy. As soon as we sat down he fell asleep on me.

"It was quite shocking. I said, ‘Where has me gregarious, beautiful son gone?’ He used to be so loving and caring and was such a joker. When he used to laugh his eyes sparkled. But sadly that was not there any more. The longer he stayed the worst he got."

Andrade-Martinez says Stephen was being given anti-psychotic drugs and a lot of them: six different drugs that added up to 6,500mg per day. She says Stephen lost the ability to walk, eat, or move his hands properly and had to be taken around the building in a wheelchair.

Before he arrived, she says, a resident psychiatrist told her they would concentrate on improving his diet and behaviour management programmes rather than medication.

This prompted her to start a petition calling on Islington social services and the local NHS trust to help.

It says: "Stephen is being let down by the institutions that are meant to be caring for him – locked up in a hospital and lost to a system that wants to tick boxes instead of care for my son."

Janet Burgess, Islington council’s executive member for health and wellbeing, told BuzzFeed News that while she couldn't comment on individual cases, "We have huge sympathy for families who want their loved ones close to home."

Burgess said: "We’re making it easier for more people with autism to live closer to home with our in-house residential service and day centre, which are accredited by the National Autistic Society.

"We have plans to build more homes for people with autism and complex disabilities in the borough, so they can be nearer to their families. This is at quite an early stage but will be a big help."

BuzzFeed News has approached Islington Clinical Commissioning Group for a comment on Stephen's case.

In a statement St Andrew's said it couldn't comment on Stephen's treatment while he was there, but added: "As the leading charitable provider of healthcare services to the NHS, St Andrew’s has the highest standards of professionalism.

"We have robust management procedures in place so we can be confident that these standards are met in providing patient care."

For every parent who's fighting to remove their intellectually disabled child from a treatment and assessment unit, there is another fighting to stop their child being placed in one in the first place.

Jon Owens, a former Metropolitan police officer of 30 years' standing and a keen amateur wrestler, alleges that his local authority and NHS doctors tried to have his son Rhys, 13, sectioned without his knowledge or consent.

He says doctors turned up at the specialist children's home where Rhys was staying on 4 September last year to detain him under the act. He says Rhys was badly bruised during the process, and that doctors then released him back to the family after an inpatient bed couldn't be found.

Owens complained to the police about this incident and also to the council and the local government ombudsman.

"While I was sleeping off a night shift they went to the children’s home and tried to section him," Owens told BuzzFeed News. "He was badly injured in the sectioning. With autistic people you don’t just turn up, they don’t like that.

"And the doctor was there for three hours frantically trying to find a hospital, St Andrew's [in Northampton] being their first choice. And when they couldn’t find one, they said, ‘Oh, you can have him now.' The injuries were incredible."

Owens also says that last year Rhys was offered a new school place – but that in an email, West Sussex county council told the school he wouldn't need the place because he was going to hospital for three months. Owens says this statement was untrue, but nevertheless Rhys lost the school place.

On Monday this week, he alleges, two doctors and a social worker arrived at his ex-partner's home in West Sussex, where Rhys currently lives. He suspects they were again attempting to detain him under the act with the aim of putting him in hospital. Again, the attempt was unsuccessful.

"My ex-partner is quite a robust lady," he said, "and she told them to go away and the words she used were… They got the meaning.

"The current game is to keep him waiting and waiting and waiting until the parents break and then we can lock him away."

Owens said he was told by the local authority in a multi-agency meeting that sectioning Rhys was "the last thing on our minds".

Owens argues that there is a profit motive for the hospitals who take autistic people for supposedly short-term assessment stays. "There's money to be made out of misery," he said.

"It’s all about money. The longer you’re in the hospital, the less they [West Sussex council] pay and the taxpayer pays. And it’s not the right place for them – it’s often a strange environment, they haven’t got the facilities, and they just drug them up and basically leave them to die."

In a statement, West Sussex Partnership NHS Trust said it couldn't comment on individual cases, but added: "We do everything we can to help children stay in their own homes where they have the support of family and friends while they undergo treatment but sometimes this is not possible and more specialist, hospital-based care is needed.

"Detaining someone under the Mental Health Act, especially a child, is not something that we do lightly. This course of action is only ever taken after careful assessment and consideration that this is what needs to happen to ensure either the person’s safety or that of others around them

A spokesperson for West Sussex county council said: "The welfare and safeguarding of any child is at the heart of everything we do within children’s social care. In this instance, county council staff have been collaborating with Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust and NHS England to ensure that the young person receives the treatment and care recommended.

“Matters such as this are highly complex and we are confident that our staff have worked with the family to ensure that the appropriate support has been offered. We have a duty of care to all children and are unable to comment in any detail on individual cases."

Sixteen-year-old Eddie Marshall, from Bristol, who is detained at a centre in Newcastle.

Whereas some families have to make an 80-mile round trip to see their child, for Adele Hanlon it's more like 600 miles.

Her son, 16-year-old Eddie Marshall – who is autistic and has ADHD, dyspraxia, and learning disabilities – was detained under the act on Christmas Day 2012. He had been struggling to cope with a new school.

Eddie was moved to St Andrew's, where he spent one year, after a place couldn't be found in his native Bristol. Then he was moved to Newcastle, where he's been ever since – meaning his family have to travel five hours there and five hours back just to see him. They only manage one trip per month and Hanlon says she's only able to make the trip because she's on maternity leave.

In a Change.org petition calling for Eddie to be brought back to Bristol, Hanlon says: "I have missed my son growing up. What we were assured would be 9 months to a year of assessment and treatment is now 3 and a half years down the line with no progression.

"Eddie should not be expected to live so far from home in such an environment – family help aid recovery and Eddie is not able to have weekly visits due to the distance."

The solutions to each of these crises are complex and require both local and national agencies to agree on a course of action using a confusing funding model that switches between different budgets.

But what all these parents agree on is that what is needed is extra care in the community to reintegrate people back into non-institutional life and to stop children and young people with intellectual disabilities falling into crisis in the first place.

Bubb told BuzzFeed News about a young woman who was in Calderstones hospital in Lancashire, the UK's only learning disability hospital, for 12 years, detained under the Mental Health Act.

"She's now in a community home run by a charity, who said she was so difficult that she would be back inside [hospital], she wouldn’t last long, she’d last maybe two or three months," he said.

"But not only is she not back inside, she’s re-established contact with her family, there is no physical restraints, she manages her own medication and she gives talks about self-harm.

"What you find is a remarkable transformation if you treat people like human beings."

The government announced last October that Calderstones, which has 223 beds, would shut this summer and that £45 million would be spent as part of a three-year plan to get patients out of institutions and back into their communities.

Jan Tregelles, CEO of Mencap, told BuzzFeed News: "The system of care for people with a learning disability, autism, and behaviour that challenges is broken. People with a learning disability shouldn’t be sent away, out of sight out of mind, to places where they are at increased risk of abuse and neglect."

Burt, the mental health minister, said: "NHS England recently announced a major programme to move people with learning disabilities out of hospital and into communities. This, and an increase in specialist staff, will transform care.

"I am committed to working with the NHS, Local Government and others to make sure this plan is delivered.

"The government’s pledge of £1.4 billion for children and young people’s mental health is one of the biggest investments the sector has seen. Local NHS services must follow our lead by increasing the amount they spend on mental health and making sure the right care is always available."