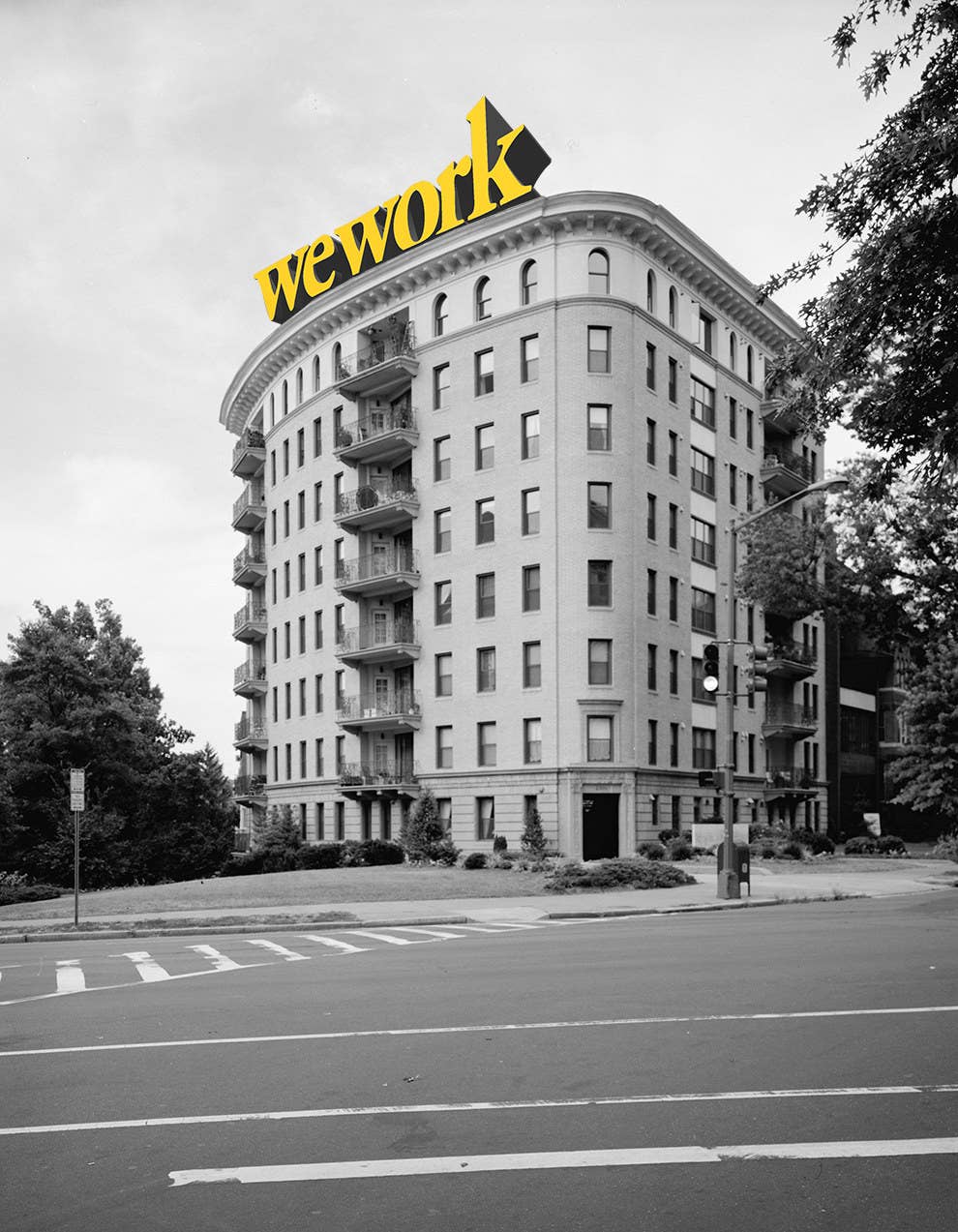

Before WeWork came knocking, the 12-story building at the corner of South Clark and 23rd streets in a grayscale office park in Crystal City was outdated and vacant. But by the time the $10 billion co-working company is done, it will be a brightly painted beacon of innovation where residents of the Washington, D.C., suburb — once a bedroom community for defense and military workers that Bloomberg Businessweek described as “a brutalist enclave of office blocs and subterranean shopping centers” — can both co-work and “co-live.” The interior will feature 360-square-foot “micro-apartments” nestled atop two floors of shared working space in a futurist vision of the ultimate in home/office efficiency. After the conversion was approved by Arlington County, one board member told a local news site that transforming “an aging, vacant office building into an innovative live–work space is an example of how we continue to reinvent Crystal City as a more attractive, vibrant place that will attract more entrepreneurs and tech workers.”

Over the past seven months or so, several sleek new real estate developments have been announced, a couple of them even venture-backed, that want to offer residents a customized version of this brand of co-living. They share some basic similarities with their Bay Area predecessors, from experimental Northern California communes to hacker hostels crammed with young software engineers who headed West because it looked exciting on HBO. All ask residents to trade personal space for the perks of group living, but the newer entrants have a different attitude toward the “communal” part of the proposition — here, the “co-” prefix is more a signifier of close quarters and plug-and-play co-habitation, rather than co-op–style shared duties, chore wheels, and elbow grease. Month-to-month rental agreements require little more than a signature and a credit card. Your chores are done for you, seamlessly, in the background. Rooms are cleaned weekly. Coordinated events make even the socializing aspect easier.

It’s a simple and intoxicating proposition — one born of the same Silicon Valley belief system that has plowed billions of dollars into on-demand apps that do your laundry, cook your meals, chauffeur you around, and clean your house, and that has so thoroughly shifted personal fulfillment to work that it's all but indistinguishable from life. The do-it-for-me rental agreement reflects an unwavering faith in better living through entrepreneurship that constantly coos: When acting in service of a Big Idea, your time is too valuable to waste.

And for those in the business of selling short-term diced-and-quartered residential space in cute city neighborhoods with an entrepreneurial gloss, there’s no moment like the present. Co-living may have been invented in the Bay Area, but now it’s being exported to places like Crystal City and Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Opportunism, after all, lives on both coasts.

The spaces in question are superficially different, but politically aligned: better designed, better funded, and way sexier versions of the group housing that came before them.

WeWork was set to launch its communal living concept (branded as WeLive) in Crystal City last month but the latest internal estimates are late fall or the end of the year. The next WeLive property is a 27-story office building in lower Manhattan. That's just the beginning. One commercial real estate insider told BuzzFeed News that in the past couple months, WeWork has also leased a “five-story plus penthouse” office building at 1161 Mission Street in San Francisco’s Mid-Market, a hub of tech company headquarters, for launching another WeLive. The 69,000-square-foot space is roughly three blocks from Twitter, four blocks from Uber, six blocks from Pinterest, and a quick hop from the luxury high-rises and controversy that followed.

WeWork may be based in New York, but signing three long-term leases before launching is pure Silicon Valley chutzpah. (Another Silicon Valley quirk? WeWork never buys, only leases, and calls it being “asset-light.”) The Crystal City project will include 252 of these micro-apartments plus amenities like an arcade, an herb garden, a library, common areas done up in fashionable neutrals, and, of course, plenty of bike parking. The Manhattan property is located at 110 Wall St., a 27-story “dark, shiny modernist tower” that was badly damaged by Hurricane Sandy. WeWork has not confirmed the San Francisco deal, but the other two buildings will include its trademark shared offices, so members presumably can toggle between co-work and co-life at will.

Meanwhile, a startup called Common has already raised $7.35 million at a $20 million valuation for a co-living network in Brooklyn neighborhoods like Crown Heights and Bedford Stuyvesant and initially planned to charge $1,750 per month. Common’s first property, a brownstone redesigned to fit 19 rooms, launches in October. Rooms will be least 80 square feet and feature at least one window. Common’s founder, Brad Hargreaves — also the co-founder of General Assembly, the startup that kicked off the “learn to code” craze — told BuzzFeed News that he will offer weekly cleaning, a set of shared supplies including coffee, paper towels, and fresh fruit. The garden floor will become a shared area that functions as a co-working space during the day and a dining room at night. That’s what users want, Hargreaves said. Many “work from their homes and co-working spaces” and end up confined to one room. “Their bed is often three feet from their desk, so it's hard to separate work and life.” Hargreaves thinks of Common as a product, and says user feedback requested “some modicum of separation.” Common’s value proposition to them is, then: “Hey, rather than working three feet from your bed, why not work a little further away?”

And The Caravanserai, which bills itself as a “global co-living subscription,” is charging $1,600 per month for access to houses in Ubud, Mexico City, and Lisbon. CEO Bruno Haid describes himself as a “founding tenant” of three co-living spaces, including 20Mission, an infamous spot in San Francisco that lets tenants pay in bitcoin.

Other startups are slowly exploring co-living concepts that look a little less like high-end hacker hostels and a little more like luxury short-term rentals, albeit ones with a faintly cooperative glow. This month, the deluxe co-working space Neuehouse — which sells itself toward “ambitious innovators” — raised $25 million. A tech investor, who reviewed the company’s pitch deck last year and passed, told Buzzfeed News that Neuehouse has looked into doing “a hotel and extended stay.” (The source requested anonymity because the investor has a working relationship with the New York–based company.) WeWork CEO Adam Neumann has been coy about WeLive and declined to speak for this article, but he has dangled the possibility of Webnb as well. “The hotel experience is an ‘I’ experience, not a ‘We’ experience,” he recently told Businessweek.

The trend risks veering into self-parody. Twitter users had trouble figuring out whether a widely shared recent piece in the New York Times real estate section was for real.

Co-living is still too nascent and disjointed to be described in certain terms. But a good place to look for clues might be WeWork, which leases short-term shared office space in 47 locations across 16 cities, and which helped pioneer the contemporary trend toward clean-lined and well-stocked communal productivity sanctuaries. Investors valued the five-year-old company at $5 billion in December, then cranked that up to jaw-dropping $10 billion last month.

It’s no coincidence that two of the main figures packaging and selling the idea of co-living to millennials outside the Bay Area — Hargreaves and Neumann — are the same people that helped make the lifestyle of a startup founder aspirational in the first place. Because WeWork is not, as its name might suggest, for workers. It’s a quasi-incubator for die-hard entrepreneurs, a “community of creators” complete with an online magazine called Creator and the yogic tagline “Do What You Love” — earnest enough to empower, vague enough not to threaten — scrawled on nearly every surface. Some WeWork co-working locations have arcades; others have bocce ball courts. The floor plans are open, the coffee is micro-roasted, the beer is craft, the music is up-tempo and anodyne. Quilted leather couches offer a change of scenery for your MacBook. Common areas facilitate collaboration. Networking is as easy as swiveling your Humanscale chair toward your nearest fellow creator. It’s not until a few weeks have passed that you start to notice that the reclaimed wood is fake, the free beer is almost always flat, and there are grown men day-sleeping on that quilted leather couch. Still, $400 a month per desk is a small price to pay for the opportunity to play Zuck.

WeWork didn’t invent co-working, but it did capitalize on prevailing macro trends, many of which originated in Silicon Valley. Freelancers, contractors, and the self-employed are now almost a third of the labor force, meaning independent office space is in higher demand than ever. In the era of always-on smartphones and the age of the “personal brand,” what we do is increasingly synonymous with who we are — as John Battelle, a tech industry veteran and author, wrote on his blog in June, “[WeWork is] attempting to scale a new kind of culture … that promises a quality workstyle, to be certain, but one that also celebrates who we are as people: we seek to find meaning in work.” And at the same time, the so-called sharing economy has imbued instant gratification with a sense of righteousness. It’s a small leap for the same Silicon Valley that convinced every Uber customer they were sharing to then sell us on spending hundreds of dollars a month for a desk and a bottomless keg because it elevates office work to the higher plane of collaboration.

But perhaps most important of all, WeWork has managed to align itself with the new American dream, updated by Silicon Valley: Get rich quick, by building a startup that changes the world. World change seems doable — every app promises that. But the actual building part can be daunting. So WeWork is part of a constellation of venture-backed services that help with the hard stuff, like learning to code or finding an inspiring office space.

Co-living offers up the same short-term leases and the same promises as co-working, except community members (it is always a “community”) get a bed instead of a desk. In both cases, practitioners sacrifice space for proximity to like-minded people and access to perks. WeLive and Common and The Caravanserai and their ilk purport, essentially, to do for the home what WeWork has already done for the office: Sweat the small stuff. Make you feel like a boss. Feed your body and your intellect. “WE TAKE CARE OF ALL THE 'STUFF', SO YOU DON'T HAVE TO ANYMORE,” The Caravanserai’s Haid promises on his website; the impossible-to-spell startup says it’s geared toward “professionals who seek a great work life balance and don't want to waste time piecing it together themselves.”

As Miguel McKelvey, WeWork’s co-founder along with Neumann, said of WeLive at a March event, “When you’re in that startup phase, where everything is hard, it would be great if that initial experience [of leasing an apartment] was a little bit easier.” And as a startup founder wrote in a post on Product Hunt, a sort of cool-hunting message board, The Caravanserai offers “peace of mind as a service.” The same people sporting “Do What You Love” T-shirts don’t need to stop when the clock strikes 5 (or 6, or 10, as the case may be). They don’t need to deal with the onerous apartment search process or cumbersome leases or landlords who are bad at email or housemates who don't grok their ambition. They don’t need to merely live — they can co-live.

Neither co-working nor co-living are exclusive to Silicon Valley, but they do reflect a boom-time belief system first seeded here in the land of startups. Innovation is infectious, and the spirit of disruption can be transferred by proximity or osmosis. With each newly minted billionaire who built a product you use, the message gets more convincing. Work can be a form of self-expression. You can retain your values and still rake it in. Just find a problem and fix it.

Bootstrapping is out of vogue. A smart person’s time is too valuable to waste — if you’re well-fed and free of distractions, there’s more time to fix the world. It’s telling that that same rhapsodic Product Hunt post about Caravanserai made reference to “how a search for a good co-working space or coffee shop” while traveling “can take up days,” or that Benjamin Dyett, who co-founded the co-working space Grind, made the place sound like an all-inclusive office resort. “If you need to send a fax, all you need to do is email to the front desk, we’ll take care of it for you,” he told BuzzFeed News. The goal is to help Grind members “get through the workday and take care of the little problems they might have. Our members don’t have to stop and think about little annoyances that happen.”

And indeed, co-living’s true believers speak of an environment in which they are all but forced to be their best selves. Ben Greenberg joined 20Mission, the co-living space in San Francisco, after dropping out of Indiana University a few years ago. The startup he was working on at the time didn’t pan out and his time as a software engineer at Lyft only lasted 10 months, but Greenberg is grateful. “Even if people fail at the startup game, it’s kind of a success, because you can meet up with all these people, start working on it, and get better at it,” he told BuzzFeed News. He credits 20Mission’s sister space in Colombia with helping him stoke his true passion: the website Glowyshit.com, where he sells “basically anything that’s awesome and glows.”

Ben Provan is the co-founder of Open Door Development, which recently opened The Canopy, a 7,000-square-foot Oakland house featuring a co-living space, a ground-floor shared workspace, and a "membership-based tea club for authentic connection." According to Provan, co-living is “ultimately a lifestyle choice,” one that offers a built-in social network and is “super-supportive” of its members “living the life they want to live.” For a resident who is “trying to entrepreneur something,” he told BuzzFeed News, co-living can help “realize your vision and realize your project.” It’s less useful for people who plan on being “out of the house eight hours a day.” Ultimately, he said, “the single reason” people choose co-living is because “it supports them in realizing their life vision and life goal.”

“Every generation has their own version” of the trend, he said, from the boomers and their communes to Israel and its kibbutzim. Here in Silicon Valley, the live–work shared home has its own mythos, albeit one that’s decidedly more DIY than, say, Common: think Mark Zuckerberg’s infamous Palo Alto hacker house, or Hewlett and Packard’s garage. Provan also drew a crucial distinction between contemporary co-living and the communes of the past. Millennials, he said, are seeking out shared living because “we all want to make a really big difference in the world. I want to create the new world that’s actually gonna work and make systemic change.”

But just as few of the WeWork-ers chugging free beer will ever see an IPO, co-living isn’t limited to just tech CEOs and systemic change-makers. In fact, Sarah Kunst, a venture partner at Future Perfect and adviser to The Caravanserai, speculated that co-living’s customer base will likely be post-college graduates who have their first job — “startup-lifestyle likers, not startup founders,” she told BuzzFeed News.

Don't knock WeWork. The addressable market size for Wannapreneurs is about $7 trillion I think. https://t.co/SFv39OheAv

When asked whether Common would be focused exclusively on game developers and other founder types — as it suggested in an early call for applicants — Hargreaves told BuzzFeed News, “I would call myself someone who rejects the traditional fetishized notion of the entrepreneur.” It’s not hard to imagine why he might want to broaden the net — after all, focusing simply on actual founders makes for quite the limited customer base.

And for WeWork’s part, “creator” is defined just broadly enough to make everyone feel special. In January, the company released a promotional video in which members speak about small business with an enraptured look in their eyes. According to the video, being a creator means making “something unique, something different — it’s to try to change the world and not be a follower.” Being a creator means getting others on board to share the “closely guarded ember of passion inside your mind.” The creators who said that founded an app for managing mobile contacts and a line of men’s dress shirts, respectively. The shirt startup has its own manifesto.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, investors are eager to help with all that self-actualization — especially right now, while the valuations are high, the landings are soft, and the money is free-flowing. At a time when entire industries are just an Uber or an Airbnb away from disruption, this coveted demographic of creators is just tossing and turning upstairs with a burning desire to innovate. A tech investor who is looking at co-living proposals told BuzzFeed News that the co-living trend is all about keeping that demo close. “The whole thing is about owning the customers,” the investor said. “They don’t ever want to let them go out of the funnel.” In that reading, co-living is nothing more than the next step of a sort of startup conveyor belt that whisks would-be founders along the pipeline as frictionlessly as possible.

Take Common, for instance. Hargreaves told BuzzFeed News that his co-living network was designed to help the typical General Assembly student, saving them from “taking a risk” on Craigslist with a strange roommate in the outer boroughs. If those same students can’t afford the $11,500 to $13,500 for General Assembly’s 12-week web development class, all they have to do is scroll to the bottom of the course page and click on the links for two different venture-backed San Francisco–based lending startups. One of those lenders, Earnest, shares an investor with Hargreaves’ co-living company, as well as with General Assembly itself. On the Earnest landing page customized for General Assembly students, it says: “Because we recognize that your participation in General Assembly is an investment in your career, we waive our normal requirement that you be employed.”

And once Common opens its doors, it will serve as the cap at the end of that padded funnel. Take your coding class, paid for with your startup loan, go co-work at your startup job, and then land, softly, on your venture-backed pillow at night.

Things could get even cushier than that. Could Hargreaves ever seen venture capitalists dropping by Common’s to see if they want to invest? “Well, potentially, absolutely. Obviously, I'm well connected to the VC world.”

But staying in the funnel makes for a very sheltered simulacrum of the life of real tech workers. While, theoretically, both co-working and co-living offer flexibility, freedom to focus, and the proximity of other people who share your passion, in reality, as these concepts get polished, corporatized, and sold to the mainstream at a premium, they may end up more like a Disneyland ride that replicates the founder lifestyle — paying for the chance to play startup. Despite Caravanserai’s sales pitch for a seamless existence, CEO Haid told BuzzFeed News that “it’s fucking boring to live in a high-rise in Soma and get all your stuff delivered.”

And as one CEO who did it the old-fashioned way told BuzzFeed News, when founders emerged from their co-working or co-living experience, “You’re like the least prepared person in the world.” People spend $100,000 thinking they will parlay it to $100 million and “live like Zuck,” said the CEO, but “it doesn’t work that way, fucker.”

In WeWork’s case, the financiers aren’t just growth junkie venture capitalists chasing anything that moves fast, but also big, multinational institutional investors. The company’s latest $433 million round of investment included JPMorgan, T. Rowe Price, and Fidelity Investments. Traditional real estate developers like Boston Properties and Rudin Management, which are partnering with WeWork on the 110 Wall St. project as well as a ground-up project in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, likewise want to get in on this demo. Real estate developers are so thirsty for TAMI tenants (short for tech, advertising, media, and internet) that the owners of the World Financial Center in lower Manhattan changed the property’s name to the more artisanal Brookfield Place.

Verizon launched a partnership to open up co-working spaces run by Grind in Verizon-owned buildings for the same reason. “Most people are at Grind because they would happily exchange job security for career fluidity since they’re working and living in a different kind of way and different realm,” Dyett told BuzzFeed News. “It’s harder for traditional companies to reach them.” Verizon is “trying to find different ways into these people’s lives — find where and how they live, where and how they work.” From there it's not hard to picture a WeLive floor sponsored by Pitney Bowes or a free BlackBerry on every nightstand.

The first Grind–Verizon space will be 140 West Street in downtown Manhattan, which is located near the offices of media companies like Condé Nast, HarperCollins, and Time Inc. Those are “the people we’re trying to attract,” said Sonya Dufner, a principal for the architecture firm Gensler, which is designing the Verizon spaces. “Ambitious, self-directed technologists” and freelancers who want “to be with the cool kids who are doing this kind of work.” How will this innovative attitude spread? From there, Dufner said, they plan to see not just “what might pollinate, but cross-pollinate.”

Jamie Russo is the president of the League of Extraordinary Coworking Spaces, a loyalty program that offers members special access to the “hottest, most reputable venues” in co-working. Last month, Russo helped “prototype” a co-living space by sleeping overnight in the Chicago location of Enerspace, her co-working company, which had been outfitted with mock-up micro-apartments. The beta test sleepover was set up by a startup called H.ME that managed to draw a crowd. The founders “put it on Airbnb and demand was through the roof,” she noted.

Because of the space constraints, features were built to serve multiple functions. The most boundary-testing dual-purpose amenity was a glass wall at the foot of the bed that could be used as a clear whiteboard during the day. Then at night, “you can privacy-screen it and turn it black” so that residents can “play Roku or stream Netflix.” According to Russo, it doesn’t feel like a fishbowl. “When you’re in it, you feel like you’re totally by yourself,” she said. “It was amazing.”

The founders declined to speak to BuzzFeed News until the concept is launched, but their experiment already appears to have worked. “One of their big learnings was that all of the rooms needed to have private restrooms,” Russo explained. The emphasis on high-design wasn't just about aesthetics or efficiency. Russo said “it totally normalizes the idea that you can really integrate work and sleep.” For business travelers, “it’s a major ordeal to stay across town and Uber back and forth.” With the co-living/co-working combo, “you totally take that out of the equation. You can live and work.” In the design she saw, Russo said living quarters included shared informal work space “if you don’t want to go down to the co-working floor.”

On the occasion of his $5 billion valuation, CEO Adam Neumann compared WeWork to his fellow sharing-economy unicorns. “We happen to need buildings just like Uber happens to need cars, just like Airbnb happens to need apartments,” he told the Wall Street Journal.

But moving into residential real estate risks running into the kind of scrutiny as Uber and Airbnb as well. One real estate executive whose company develops commercial properties in New York told BuzzFeed News that WeWork is especially vulnerable. “They don’t strike me as particularly politically savvy,” the source noted, pointing out that WeWork has already angered 32BJ SEIU, a powerful union in New York, by using nonunion cleaners (not cleaning up after yourself is one of those perks in the background offered to WeWork members). WeWork uses a contractor that pays workers half the standard wage of New York City janitors, who are unionized. After the protests, a local unit of the Service Employees International Union filed a complaint alleging that WeWork threatened to fire the cleaners if they unionized. Workers said they began hearing that they might not have jobs. A WeWork spokesperson said it was the contractor who terminated its relationship with WeWork and that WeWork was trying to “make sure we have uninterrupted cleaning service for our members.”

And housing is particularly polarizing. Hargreaves, for example, was very careful to emphasize that Common will only take “vacant market rate buildings,” because it’s really important to the company that it doesn’t jeopardize rent-stabilized housing. Provan, meanwhile, said he has an “an uphill battle” convincing traditional real estate investors about the concept as well. “But when you talk to a 28-year-old, they’re like, ‘It’s great! When’s the next one open?’”

Before declaring bankruptcy this summer, Campus, a co-living network run by a Peter Thiel fellow named Tom Currier, had plans to expand its network of 30-some co-living spaces to the Upper East Side. In an apology to the 150 residents he left stranded, Currier said: “Despite continued attempts to alter the company’s current business model and explore alternative ones, we were unable to make Campus into an economically viable business."

As 21st-century labor expectations have made “work-life balance” into a joke, the new shorthand for scheduling anything personal outside the office is “work-life integration.” Both Russo and Dufner said that integration was simply more realistic. Both also argued that co-living, by its very nature, acknowledges that work and life have been synonymous for awhile. “Work-life balance is trying to limit one or the other,” Russo explained, “but people just don’t think that way anymore. People are really integrating. They want work to feel enjoyable.”

In a co-living building, she reasoned, “if you’re working at 9 o’clock at night,” you can leave your micro-room and not feel like the lone workaholic. And after all, Zuckerberg’s famous hacker house wasn’t started out of a deep-seated philosophical desire to pool resources — it came from the need to be able to work 24/7 on a unified product with a unified team while saving money on office space.

According to Dufner, packaged co-working/co-living deals, like 110 Wall St., sound friendly to young, driven families. “We all know that the workday has gotten longer and longer,” she said, and living where you work allows people with families to take a break and come right back. “You’re eliminating all the commuting time.”

The bad actor in the equation didn’t seem to be the fact that life has ceded control to work, but that balance was never achievable to begin with. “People think the word ‘balance’ isn’t necessarily true,” she said. “Where does work stop and life start? It’s kind of all one.”

But Russo conceded, “I guess one downside might be is if you live in a live–work space you always feel like you might be working.”

The co-living prototype experiment was conducted at Enerspace by the company H.ME. An earlier version of this article misstated its name and testing location.